Quality Assurance of Higher Education in the South Caucusus

23 Oct 2018

By Diana Lezhava, Mariam Amashukeli, Edith Soghomonyan and Gohar Hovhannisyan for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Seurity Studies in the Caucasus Analytical Digest on September 28. external pageImage courtesycall_made of Paata Vardanashvili/wikimedia. external page(CC BY 2.0)call_made

Introduction by the Special Editor, Diana Lezhava, Tbilisi State University

The quality of higher education and compliance with quality assurance mechanisms given in the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance (ESG) of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) have been a hot topic of discussion for many years and pose substantial challenges for a number of the Bologna participant states. This is especially true for the South Caucasus countries that joined the Bologna Process at the Bergen Ministerial Conference in 2005. Despite the numerous reforms that aimed to advance the quality of higher education, such as the introduction of internal and external quality assurance mechanisms and the establishment of national quality assurance offices, there still are certain areas that need particular attention and improvements.

This issue of the Caucasus Analytical Digest addresses this topic and features three papers: two papers discuss the Georgian higher education system, and the third paper focuses on the Armenian experience. The case of Azerbaijan is not discussed in this issue, since a separate issue in 2019 will be dedicated to higher education in Azerbaijan.

In this issue, the first article by Mariam Amashukeli discusses the internationalization of higher education and argues that it can serve as both a mechanism of quality assurance and a strong instrument for boosting the quality of education in Georgia. The second article by Diana Lezhava reviews the practices of external quality assurance in Georgia and argues that the autonomy of the national quality assurance agency and independence of the university licensing processes (institutional authorization and programme accreditation) from the state is crucial for improving the overall performance of universities. The third article by Edith Soghomonyan and Gohar Hovhannisyan tackles the underrepresentation of student bodies in the quality assurance system in Armenia and argues that students’ lack of motivation and awareness prevents them from full participation in the process of quality assurance at higher education institutions.

The Role of Internationalization for Quality Assurance in Higher Education Systems: The Case of Georgia

By Mariam Amashukeli, Tbilisi State University

DOI: 10.3929/ethz-b-000292932

Abstract

Internationalization and quality assurance in higher education systems are strongly interrelated dimensions. Overall, internationalization of higher education has a strong positive undercurrent, as it is expected to serve teaching, learning and research quality enhancement, technological innovation, economic development and social well-being. Thus, internationalization should not be understood as an ultimate objective in itself but as a means to enhance higher education quality at large. Considering that the Georgian higher education system still encounters significant challenges in the provision of high-quality academic services (even after 13 years since joining the Bologna process), the present paper reflects on the internationalization policies and practices in Georgian higher education.

Introduction

Internationalization of higher education (IHE) envisages integrating international, intercultural and global dimensions in national higher education policy (Knight 2008). Over the years, its main focus was on increasing the physical international mobility between universities. However, since the Mobility Strategy 2020 (EHEA 2012) was amended in 2012, fostering “comprehensive internationalization” (Hudzik 2011) became one of the main targets of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). According to this concept, internationalization is defined as a shared and equally recognized value for the administration of higher education institutions (HEIs), as well as for students and faculties. This value should be integrated into teaching, research and all services provided at universities. IHE is an “institutional imperative” (ibid. p. 7) and a “response” to globalization that is extremely necessary for the higher education system to meet the challenges of globalized economy and communications having direct impact on the daily lives of individuals (Hudzik 2011).Today, international higher education represents a very wide range of forms, directions and approaches. International recruitment of students, training of graduates for employment on the global market, franchising of universities and academic programmes, export of products of national education, attraction of international talent and online learning have become important components of IHE over the last ten years (de Wit et al 2015).

There are two broad categories of IHE discussed at the international scale: internationalization abroad and internationalization at home. The main components of internationalization abroad are international credit/ staff/degree mobility and transnational education (university branches/overseas campuses, franchise of academic programmes, virtual/e-mobility of programmes), whereas internationalization at home is more focused on incorporating global perspective into national education goals, content, teaching methods and assessment systems. Thus, internationalization of the national curriculum makes international education available for all students instead of only those benefitting from physical mobility (de Wit et al 2015, pp. 41–58).

In the context of recent developments worldwide, IHE is discussed in strongly positive correlation with increasing quality of academic programmes and research, contributing to economic growth and enhancing the prestige of HEIs (Martin & Parikh 2017, p. 61). According to the 4th Global Survey on Internationalization of Higher Education, the improved quality of teaching and learning is the top ranked benefit, especially across higher education institutions in Europe and the Middle East (Egron-Polak & Hudson 2014, p. 9). For the drivers of internationalization, the management and international office of HEIs are seen as the most important internal factors for internationalization, whereas the national/regional policies are ranked as the top external drivers by the European HEIs (ibid., p. 9).

Overview of IHE in Georgia

In retrospect, on a large scale, IHE in Georgia started in 2005 when the state joined the Bologna Process at the Bergen Summit and later became a member of EHEA. Internationalization of higher education gained a new political-economic perspective after signing the EU-Georgia Association Agreement in 2014 as it envisages improvement of higher education quality and its compatibility with the EU higher education modernization agenda. The importance of IHE is also reflected in the Law of Georgia on Higher Education,Socio-Economic Development Strategy 2020 and the Education and Science Strategic Development Document 2017– 2021. The above-mentioned documents clearly identify the important role of education in the success of Georgia’s European integration process, the establishment of democratic values and the accumulation of competitive human capital/workforce.

I would like to specifically emphasize the strategic document 2017–2021 and its following action plan, which consider and discuss internationalization of Georgian HEIs in line with enhancing the overall educational quality (Strategy of Education and Science of Georgia 2017–2021, p. 36). It will not be an exaggeration to say that IHE is officially regulated at the national level for the first time by this strategic document. The important role of renewed national authorization and programme accreditation standards for higher education institutions should also be mentioned, as they are currently the actual (external) enforcement mechanisms for IHE in Georgia (this point will be discussed more thoroughly below). In turn, both standards are updated in accordance with the guidelines for the external quality assurance in EHEA in frames of the Quality Assurance Reform for Georgian Higher Education launched in 2015. The reform envisaged a number of legal amendments related to the national authorization and accreditation standards as well as procedures issued by the Georgian Ministry of Education and Science.

The new wave of national authorization and accreditation for HEIs began in the spring of 2018. Currently, 30 universities and 29 teaching universities and colleges in total (both public and private), operating in Georgia,are obliged to participate in the above-mentioned procedures. These evaluations are mandatory for all HEIs to be recognized by the state and gain eligibility for implementing educational activities (National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement).

It is important to mention that the new authorization document envisages elaboration of internationalization policy, mechanisms and assessment of their effectiveness as one of the mandatory criteria/indicators for the evaluation of the organizational structure and management of HEIs. This particular sub-standard addresses the international mobility of students and staff (inbound, outbound), plans for attracting international students/staff, joint degree programmes, etc. (Authorization Standards for Higher Education Institutions, p. 2). Internationalization of research is another sub-standard for evaluating Georgian HEIs. Implementing joint research projects and PhD programmes, practising institutional cooperation with EU-based universities and international research organizations, etc., are defined as the assessment criteria for the above-mentioned sub-standard (ibid, p. 13).Therefore, the rather detailed authorization standards made the Georgian HEIs somewhat “obliged” to meet the requirements through developing internal policies for internationalization and reflect on its importance for enhancing the education overall quality.

The internationalization component of national accreditation standards is mainly related to internationalization in the home category. For instance, it evaluates the courses of academic programmes based on syllabi. According to the evaluation criteria, teaching literature/ readings listed in syllabi should be in compliance with the modern scientific discussions and research updates in the particular field(s). Thus, the overall curriculum of the academic programme should meet these requirements (Accreditation Standards for Higher Education Programs, pp. 4–5). Additionally, several sub-standards envisage the evaluation of teaching practice of the academic/invited staff by their [Georgian or foreign] peers (if necessary), aiming to enhance the teaching quality (ibid, p. 18) and, if applicable, even the assessment of the internationalization strategies for the academic programmes (ibid, p. 1). However, these two aims can be articulated as more supportive (or encouraging) evaluation criteria rather than mandatory requirements that the Georgian HEIs should meet for programme accreditation.

In view of the above considerations, we can assume that the new authorization-accreditation standards as external quality assurance mechanisms made internationalization an integral part and “institutional imperative” (Hudzik, 2011). This development should be acknowledged as an important step forward with respect to the internationalization of the Georgian higher education system. The country’s progress is reflected in the Bologna Process Implementation Report 2018, as well. In 2015, Georgia was positioned with the countries not having national internationalization strategies and with zero percentage of higher education institutions having their internal internationalization policies (The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Bologna Process Implementation Report, pp. 211–216). Today, Georgia is ranked among the countries with national strategies for internationalization of higher education and with a 1–25% estimated percentage of higher education institutions that have adopted internationalization policies (The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report, pp. 242–244). This percentage is expected to be much higher now as the reference year for the data collection for the Bologna Process report 2018 is the first half of 2017 (ibid., pp. 19–20), whereas the national authorization requiring the Georgian HEIs to have the internationalization policies began only in spring 2018.

Having greater opportunities for students/academic staff mobility is one of the key achievements of Georgia with respect to internationalization. This achievement was made possible by the introduction of the ECTS system and three-tier higher education in the Georgian national education system. International mobility is mostly implemented with the financial support of framework programmes such as Erasmus+, DAAD, and the International Education Center (IEC) as well as through bilateral partnerships between Georgian and foreign universities (Lezhava & Amashukeli, 2016, p. 160).For instance, more than 500 applicants received financial support from the IEC in 2014–2017 (Annual report 2017), which provides state scholarships for young professionals to earn their academic degrees internationally. In addition, according to the National Statistics office of Georgia, the overall number of outbound students reached 582 in 2017–2018 (Statistics for Higher Education 2018).

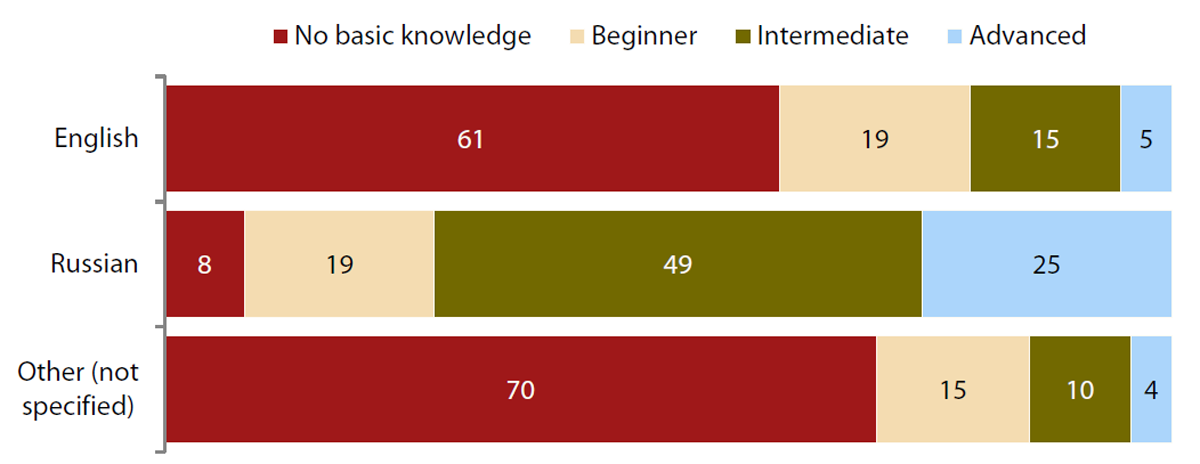

However, as discussed in the study of Lezhava and Amashukeli (2016, pp. 142–163), there are a number of challenges that Georgian universities face in their way to internationalization. One of the main obstacles is insufficient knowledge of English among the academic staff (especially older generations) and students. This is a hindering factor for developing modern academic programmes, updating existing study courses or developing solid English language academic programmes to attract international students and academic staff from European countries/universities (ibid., pp. 142–143). If we look at the latest Georgian household survey results, it is obvious that the majority of the population feels more comfortable with the Russian language: in total, 74% of the respondents indicate intermediate and advanced knowledge of Russian, whereas only 20% of them indicate intermediate and advanced knowledge of the English language (See Figure 1 overleaf). Within the 18–35 yea age category, the percentage of the population with intermediate and advanced knowledge of English is the highest (42%) compared to their older (36+ years) counterparts (Caucasus Barometer 2017).

Considering that the National Strategy for Education and Science 2017–2021 and its following action plan 2017–2018 envisage the introduction of supportive programmes for the professional development of academic staff and for attracting new generation of academics at the Georgian HEIs (Education and Science Strategic Development Document 2017–2021, p. 65), hopefully,the problem of English proficiency will be addressed as well.

Figure 1: Knowledge of Foreign Language (among Georgians) (%)

Conclusion

After this brief review of the current situation of IHE in Georgia, we would like to add that strengthening the focus on the policy and practice of internationalization at home (IaH) (by both the state and the HEIs) would be extremely useful for increasing the overall quality of higher education services at the national level. However, international mobility has played a significant role here in the early 2000s. IaH emerged as a response to the leading focus on mobility, benefiting only a small number of students. Thus, it is important to ensure that the international dimension is present at the domestic level and equally available for all students (de Wit, et al., 2015, pp. 49–52).

As the term [IaH] itself is quite complex, it is not always clear and understandable how university management and/or faculty members should develop and implement internationalized curricula at HEIs (Green and Whitsed 2015, cited in de Wit et al. 2015, p. 50). As already mentioned, the main idea of IaH is “the incorporation of international,intercultural and/or global dimensions into the content of the curriculum as well as the learning outcomes, assessment tasks, teaching methods and support services of a program of study” (Leask 2015, p. 9, cited in de Wit et al. 2015, pp. 50). To foster the IaH dimension at large, there are various “tools” available for HEIs, such as “comparative international literature, guest lectures by speakers from local cultural groups or international companies, guest lecturers of international partner universities, international case studies and practice or, increasingly, digital learning and on-line collaboration. Indeed, technology-based solutions can ensure equal access to internationalization opportunities for all students” (Beelen and Jones 2015, cited in de Wit et al. 2015, pp. 50–51). Therefore, as a starting point, it would be highly beneficial for the overall Georgian higher education system to put more focus on the IaH dimension in Education and Science Strategic Development Document 2017–2021 and its following action plans and to make the evaluation criteria of the IaH component bolder in the national authorization/accreditation standards.

References

- Association Agreement between the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community and their Member States, of the one part, and Georgia, of the other part 2014, entered into force 1 July 2014.

- Beelen, J. & Jones, E. 2015,Redefining Internationalization at Home. Bucharest, Romania: Bologna Researchers Conference.

- De Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L. & Egron-Polak, E. 2015,Internationalization of Higher education, European Union.

- Egron-Polak, E., & Hudson, R. 2014,Internationalization of Higher Education: Growing Expectations, Fundamental Values IAU 4th Global Survey. International Association of Universities (IAU)

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015. The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2018. The European Higher Education Area in 2018:

- Bologna Process Implementation Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Higher Education Area, 2012, Mobility for Better Learning: Mobility strategy 2020 for the European Higher Education Area (EHEA).Available from: <https://www.cmepius.si/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2012- EHEA-Mobility-Strategy.pdf>. Accessed 21.08.2018

- Government of Georgia 2014, Approval of the Socio-Economic Development Strategy “Georgia 2020”, resolution N400. Available from: <https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/2373855>. Accessed 19.08.2018

- Government of Georgia 2017, Approval of the Strategy of Education and Science of Georgia 2017 – 2021, resolution N533. Available from: <https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/3924876>. Accessed 19.08.2018

- Green, W. and Whitsed, C. (Eds.), 2015. Critical Perspectives on Internationalizing the Curriculum in Disciplines. Sense Publishers.

- Hudzik, J.K. 2011,Comprehensive Internationalization: From Concept to Action, NAFSA: Association of International Educators, Washington, D.C.

- International Education Center (Georgia), Annual Report 2017. Available from: <http://iec.gov.ge/4282>. Accessed 17.08.2018

- Knight, J. 2008,Higher Education in Turmoil: the Changing World of Internationalization, Sense Publishers, Rotterdam.

- Leask, B. 2015,Internationalizing the Curriculum. London: Routledge.

- Lezhava, D., & Amashukeli, M. 2015,Compatibility of Academic Programmes Outcomes with Labour Market Demands in Georgia. Center for Social Sciences. Tbilisi: Nekeri

- Law of Georgia on Higher Education 2004. Available from: <https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/32830>. Accessed 19.08.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement 2017, Authorization Standards for Higher Education Institutions. Available from: <https://eqe.ge/eng/static/517/HE-QA>. Accessed 15.08.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement 2017, Accreditation Standards for Higher Education Programs. Available from: <https://eqe.ge/eng/static/519/HE-QA/>. Accessed 15.08.2018

- National Statistics Office of Georgia 2018, Statistics for Higher Education: Number of Students Studying Abroad and Foreign Students. Available from: <http://www.geostat.ge>. Accessed 17.08.2018

- The Caucasus Research Resource Centers, 2017,Caucasus Barometer Survey Available from: <http://caucasusbarometer. org/en/>. Accessed 19.08.2018.

About the Author

Mariam Amashukeli is a PhD student of Sociology at the Tbilisi State University. Since 2012, Ms Amashukeli has been an affiliated researcher at the Center for Social Sciences (CSS).

External Quality Assurance: State Leverage over Higher Education Institutions or Means for Increasing the Quality of Education?

By Diana Lezhava, Tbilisi State Universtiy

DOI: 10.3929/ethz-b-000292932

Abstract

Joining the Bologna Process in 2005 was the first attempt by the Georgian government to transform its higher education system from a Soviet-style system into a European one. A number of reforms have been implemented since then, including the introduction of an external quality assurance process conducted by the state agency under the aegis of the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. The state licensing system, envisaging institutional authorization for higher education institutions and accreditation for academic programmes, has also undergone numerous changes over years, including the recent adoption of new standards. This process has been accompanied by serious criticism, starting from being used as a means of state leverage and a political tool and ending with its ineffectiveness due to being administered only superficially. The present paper reflects on the challenges accompanying this process and discusses how the mechanism of external quality assurance can serve as an instrument for raising the quality of education.

Introduction

Following the Rose Revolution of 2003, the newly formed revolutionary government, trying to fundamentally transform a post-Soviet, heavily corrupt Georgia into a state with a clear European vision and aspirations, introduced active reforms at all levels of education. In the case of higher education, this process started in 2004 by adopting a new Law on Higher Education and joining the ongoing Bologna Process, which was initiated in European countries in 1999. The Bologna process envisaged the creation of the European Higher Education Area for facilitating student mobility, creating an easily recognizable and comparable degree system, establishing specific quality assurance mechanisms for providing high quality education among the Bologna participant countries, and supporting the so-called European dimension in higher education (Bologna Declaration, 1999). Thus, it seemed an obvious choice for Georgia that would enable the country to challenge its Soviet legacy in the higher education system (Glonti & Chitashvili 2006).

Therefore, considering the Bologna requirements, the Georgian higher education system started to rebuild itself and align with the European model of university education. Among other things, this undertaking envisaged the creation of a quality assurance system within and outside universities, in particular, the introduction of a national quality assurance agency, establishment of quality assurance units within higher education institutions, and introduction of external quality assurance mechanisms in the form of institutional authorization and programme accreditation—a state licensing system for higher education institutions. The last item met with serious criticism from the academic community, part of which accused the state agencies of deploying external quality assurance mechanisms as a state leverage over universities, while the second part blamed the state for using this mechanism only formally without substantial investigation that hindered the improvement of the quality of higher education in Georgia (Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016).

The present paper intends to reflect on the existing challenges and problems related to external quality assurance mechanisms and discuss their potential to be used as a political leverage or to increase the quality of education.

External Quality Assurance Mechanisms

Quality assurance of higher education is regulated by the Law of Georgia on Higher Education, which defines the internal and external quality assurance procedures based on the Bologna Process and its normative documents (Prague Communique 2001; Berlin Communique 2003). In particular, the Law demands the introduction of quality assurance units/departments at higher education institutions and considers such units to be one of the major managerial bodies of the university (Law of Georgia on Higher Education, Art 15.2). The Law also regulates internal and external quality assurance mechanisms. While universities are given the freedom to define which mechanisms they will use for internal monitoring, the Law establishes the external ones, i.e., state authorization and accreditation (Ibid, Art 25.2, Art 2B1, Art 2T). The Law also regulates that the National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement (NCEQE), which operates under the aegis of the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport of Georgia and is responsible for external quality assurance (Ibid, Art 56.4).

Authorization, as defined by the Law and NCEQE, is “an institutional evaluation, which determines compliance of an institution with the authorization standards” (Eqe.ge, n.d). The authorization procedure is performed by a panel of independent experts, and based on their assessment, the decision of granting or denying authorization is made by a special committee. While the NCEQE itself is a legally independent entity, it still operates under the aegis of the Ministry of Education, namely, its head is appointed by the Minister him/herself, which deprives NCEQE of real autonomy (Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016). The members and the Chair of the Authorization Council are not appointed by the Director of the NCEQE or the Minister of Education directly (the latter only nominates the candidates) but by the Prime Minister (Eqe.ge, n.d). At first glance, this method would seem to guarantee greater autonomy for the Council, as it does not directly depend on the Ministry of Education or the Center. However, the fact that there are no clear criteria or procedures for selecting the candidates for membership (Eqe.ge, n.d) suggests that the Minister of Education has absolute freedom of choice that in the end may influence the outcome, i.e., Authorization Council decisions.

Accreditation is performed in a similar manner: academic programmes are assessed by field experts, and the decision is made by the Accreditation Council, the members and Chair of which are appointed by the Prime Minister (Eqe.ge, n.d.).

Both the accreditation and authorization processes that officially started in 2010 (before that only institutional accreditation was performed) had numerous problems and were thus heavily criticized. One of the major problems associated with accreditation was its links to state funding. In particular, according to the Law on Higher Education, state funding, which is granted to students based on the Unified National Exams,1 can be approved for accredited academic programmes only (Law of Georgia on Higher Education, Art 63.3). This provision was basically initiated to force Georgian universities, which clearly lacked experience in using external assessments for quality assurance, to undergo the accreditation process. Since students’ state scholarships represent the only source of state funding for higher education institutions (Chakhaia 2013), this provision worked and still continues to work as a perfect motivator not to lose students, i.e., not to lose their source of income. According to various studies, this linkage between accreditation and state funding resulted in a high number of accredited academic programmes [1679] (Eqe.ge, n.d) and a low-quality accreditation process (Darchia 2013; Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016). In addition, theoretically, this linkage gives the state the opportunity to reduce the amount of funding allotted to universities by depriving accreditation to academic programmes, i.e., less accredited programmes, and thereby granting less state money to the universities.

The low quality of the accreditation process was also connected with the scarcity of human resources; due to the small size of the Georgian academic community, certain academic programmes were evaluated by non-field experts. In addition, due to the specificity of Georgian culture with strong bonding capital (CRRC 2011), the accreditation process was accused of being nepotistic when academic programmes were assessed by their staff’s friends/acquaintances without critical evaluation (Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016)

The state authorization process had similar problems. In this case, the lack of proper authorization standards targeting the institutional development of universities was a prevailing problem. In addition, rather vague assessment criteria and indicators made the whole authorization process rigid and not oriented to the development of university performance (Darchia 2013). Again, in this case, the process was considered to be rather formal.

In general, as mentioned above, both accreditation and authorization were met with a hostile attitude by the academic community in the universities. NCEQE was even referred to as a “punitive organization” that is used by the state in its own interests to control the universities due to lack of autonomy of the Center. In addition, the process was accused of placing a greater emphasis on the formal parameters, such as the formal distribution of credits and the description of material resources, and in general, verifying the technical-material base rather than substantively assessing the programmes for quality (Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016). Thus, the Georgian academic community distrusted the whole process. It should be mentioned that distrust towards the state licensing system is not solely characteristic of Georgia but is rather a global phenomenon deeply rooted in the “historical lack of formal organizational and institutional arrangements” (Stensaker & Maassen 2015). This distrust is especially relevant in post-communist states, which are characterized by a vastly increasing number of newly formed universities in the post-Soviet era (Scott 2002 as cited in Geven & Maricut 2015). For instance, by the 2000–01 academic year, there were more than 171 higher education institutions in Georgia, and among them, only 26 were public; the rest were private. This number reached 198 by 2004–05 and gradually decreased to 752 by the beginning of the 2017–18 academic year (Geostat.ge, n.d.). According to various studies, the post-Soviet states are marked by a strategic approach to external quality assurance procedures, i.e., first, formally meet the standard criteria (Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016) and later, ignore self-evaluation and “do whatever you want” (Geven & Maricut 2015).

Current State of Affairs

Considering the abovementioned criticism, the NCEQE updated the standards for both accreditation and authorization in 2017 and introduced an internationalization dimension into the evaluation process, i.e., expert panels are always chaired by an international expert, reducing the possibility of nepotistic evaluation. Since the second wave of authorization/accreditation has started only recently and is still in progress (2017–2018), it is too early to make a preliminary evaluation of its performance. However, it is still possible to assess the attitude of the Georgian academic community towards these changes. First, it should be mentioned that newly developed standards, especially in the case of authorization, elicit fear among academics and university administrators, some of whom accuse the state of being too willing to drastically decrease the number of universities (Fortuna.ge 2018). In fact, this fear was proven to be valid by government officials when both the Minister of Education and the Prime Minister emphasized multiple times that due to the new cycle of authorization, the number of universities would be reduced (Imedinews.ge, 30.12.2017; bm.ge, 21.12.2017). Meanwhile, it became obvious that the majority of universities would not be able to meet the standards, which were adopted based on the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG) to meet the European standard of educational quality, thus resulting in the closure of a large number of active educational institutions in Georgia. This has occurred since the beginning of 2018, when the Authorization Council deprived 7 institutions of their status as higher education institutions, one of which closed because it was unable to meet the standard even before the authorization visit started (Decrees of Authorization Council, Decree No. 1, 15.02.2018; Decree No. 3, 15.02.2018; Decree No. 5, 22.02.2018; Decree No. 43, 28.06.2018; Decree No. 44, 28.06.2018; Decree No. 47, 17.08.2018; Decree 48, 17.08.2018). Therefore, the total number of higher education institutions further decreased from 75 to 68 by September 2018, of which 60 are authorized by the NCEQE, and 8 are authorized by the Orthodox Church of Georgia (Eqe.ge, n.d.).

On the other hand, the true problem lies not in the standards per se but the formal character of the Bologna reforms implemented by the Georgian higher education system (Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016). In particular, the universities transformed their performance on a more normative level rather than in practice. This rather formal implementation of the Bologna principles resulted in an inability to meet high standards of teaching or research and thus made universities vulnerable to strict state licensing processes. In addition, the dependence of the NCEQE on the state creates fruitful ground for the state to exercise its political leverage over higher education institutions, i.e., manipulate the accreditation and authorization processes.

Conclusion

Considering the abovementioned, it is obvious that the Georgian higher education system is underperforming in terms of quality of teaching, learning and research, which is evidenced by a number of studies (Kapanadze et al 2014; Amashukeli et al 2017; Lezhava & Amashukeli 2016; Performance Audit Report 2016; Performance Audit Report 2016b). Therefore, strict quality assurance rules may decrease the number of higher education institutions to a more reasonable figure and consolidate the scattered human resources in the universities to facilitate high-quality teaching and research. On the other hand, there is also a possibility that strict rules introduced by the state may result in hostility, distrust and resistance from the academic community, as well as the use of political leverage by the state. Therefore, to increase the quality of education and grant credibility to the state licensing system, in addition to the absolute need for the high performance of the accreditation and authorization processes, it is of the utmost importance to support universities to meet these standards. If the state prioritizes education and recognizes its inevitable effect on the development of the country at large (Strategy of Socio-Economic Development of Georgia 2020), then it should also support the development of higher education institutions. To improve the quality of education, not only should rules become stricter, but the NCEQE should be granted real autonomy to eliminate any potential influence by the state. Moreover, resources should be provided for universities to initiate internal reforms that would enable them to raise the quality of teaching and research and thus be able to meet state expectations.

Notes

1 According to the current procedures, which were initiated after the Rose Revolution, university admission is highly centralized under the state. In particular, the National Assessment and Examination Center (NAEC), operating under the aegis of the Ministry of Education, conducts unified national exams on an annual basis, and based on their scores, applicants are admitted to various universities. In other words, universities do not have any leverage or authority over admission decisions at the undergraduate level. Every September, the NAEC gives universities a list of new students who met or exceeded the admission threshold and have chosen a particular university. A similar scheme is implemented at the master’s level; however, in this case, universities have the right to administer internal exams and make admission decisions based on those results. In the case of PhD programmes, the state does not interfere, and the whole process is organized by universities. This centralized system was introduced to abolish the corrupt practices of admission that largely dominated in the pre-revolutionary period and establish a merit-based process.

2 This figure comprises the total number of higher education institutions, including private and public institutions, authorized by the NCEQE. Orthodox Divinity Higher Educational Institutions do not fall under state authorization and are authorized by the Orthodox Church of Georgia.

References

- Amashukeli, M., Lezhava, D. & Gugushvili, N. 2017, Education Return, Labour Market and Job Satisfaction in Georgia, Center for Social Sciences, Tbilisi. Available from: http://css.ge/index.php?lang_id=ENG&sec_id=24&info_id=1308

- Bm.ge 21.12.2017, უნივერსიტეტების რაოდენობას შევამცირებთ [We Will Decrease the Number of Universities], <http://www.bm.ge/ka/article/quotuniversitetebis-raodenobas-shevamcirebtquot/15899>. Accessed 12.09.2018.

- Caucasus Research Resource Centers 2011, An Assessment of Social Capital in Georgia. Briefing Paper. Available from <http://crrc.ge/uploads/tinymce/documents/Completed-projects/CRRC_Social_Capital_Briefing_Paper.pdf>

- Chakhaia, L. 2013, Funding and Financial Management of Higher Education and Research, Strategic Development of Higher Education and Science in Georgia Policy: Analysis of Higher Education according to Five Strategic Directions, The International

- Institute for Education Policy, Planning and Management, Tbilisi. Available from: <https://drive. google.com/file/d/0B9RC0lzxlY4ZVnl4YTh5M01Ecmc/view>

- Darchia, I. 2013, Quality Assurance, Strategic Development of Higher Education and Science in Georgia Policy: Analysis of Higher Education according to Five Strategic Directions, The International Institute for Education Policy, Planning and Management, Tbilisi. Available from: <https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9RC0lzxlY4ZTnRpVEJ2NHBmWlU/ view>

- Fortuna.ge 14.02.2018, GIPA-ს უკვე მეორე პროგრამის აკრედიტაციას უუქმებენ – რეფორმა ერთ-ერთი ყველაზე რეიტინგული უნივერსიტეტის წინააღმდეგ [GIPA is Already Deprived the Accreditation of Second Program—The Reform against One of the Most Highly-ranked University], <http:// fortuna.ge/gipa-s-ukve-meore-programis-akreditacias-uuqmeben-reforma-ert-erti-yvelaze-reitinguli-universitetis-winaaghmdeg/>. Accessed 09.08.2018

- Geven, K. & Maricut A. 2013, Forms in Search of Substance: Quality and Evaluation in Romanian Universities, European Educational Research Journal, Vol. 14(1) 113–125, DOI: 10.1177/1474904114565151

- Glonti, L. & Chitashvili, M. 2006, ‘The Challenge of Bologna: The Nuts and Bolts of Higher Education Reform in Georgia’, in V. Tomusk (ed), Creating the European Area of Higher Education. Voices from Perophery, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 209-226.

- Government of Georgia 2014, Strategy of Socio-economic Development of Georgia 2020, Available from: <http:// www.economy.ge/uploads/ecopolitic/2020/saqartvelo_2020.pdf>. Accessed 12.09.2018

- Imedinews.ge 30.12.2017, ჩხენკელი: უნივერსიტეტების რაოდენობა სავარაუდოდ შემცირდება [Chkhenkeli: Most Probably the Number of Universities Will Decrease]. Accessed 12.09.2018

- Kapanadze, S., Maghlakelidze, M., Tskhadaia, G., Tarkhan-Mouravi, A., Martskvishvili, K., Mukhiguli, K., Basilaia, E., Gabashvili, M. & Dvalishvili, D. 2014, Analyzing Ways to Promote Research in Social Sciences in Georgia’s Higher Education Institutions, Policy

- Paper, Georgia’s Reforms Associates. Available from: <http://grass.org.ge/ wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Policy_Paper_research_in_social_sciences_ENG.pdf>

- Legislative Herald of Georgia 2004, Law of Georgia on Higher Education. Available from: <https://matsne.gov.ge/ en/document/view/32830#>

- Lezhava, D. & Amashukeli, M. 2016, Assessment of Bologna Process in Georgia: Main Achievements and Challenges, Center for Social Sciences, Tbilisi.

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement, n.d. About Authorization, <https://eqe.ge/eng/static/517/ HE-QA/>. Accessed 27.07.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement, n.d. Accreditation Council, <https://eqe.ge/geo/static/555/ HE-QA//Accreditation-Council>. Accessed 27.07.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement, n.d. Authorization Council,< https://eqe.ge/geo/static/455/ HE-QA//>. Accessed 27.07.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement, n.d. List of Accredited Programs, <https://eqe.ge/geo/ static/591/register/>. Accessed 09.08.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement, n.d. List of Higher Education Institutions, <https://eqe.ge/ eng/static/89/register/heis>. Accessed 12.09.2018

- National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement, n.d. FAQ—How the Members of Authorization Council are Selected? <https://eqe.gov.ge//geo/faq/category/8>. Accessed 12.09.2018

- National Statistics Office of Georgia, n.d. Higher Education Institutions and Enrolment by Type of Study. <http:// geostat.ge/index.php?action=page&p_id=2105&lang=eng>. Accessed 12.09.2018

- State Audit Office of Georgia, 2016, Assurance of Acceptable Quality Education for Students at the Higher Education Institutions. Performance Audit Report. Available from: <https://sao.ge/files/auditi/auditis-angarishebi/2016/ HEIs.pdf>

- State Audit Office of Georgia, 2016b, External Quality Assurance of Higher Education. Performance Audit Measures Taken by the National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement. Available from: <https://sao.ge/files/auditi/auditis-angarishebi/2016/eqe-Education-Quality-Assurance.pdf>

- Stensake, B. & Maassen, P. 2015, A Conceptualisation of Available Trust-building Mechanisms for International Quality Assurance of Higher Education, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, Vol. 37, No. 1, 30–40, DOI: <10.1080/1360080X.2014.991538>

- The European Higher Education Area, 1999, The Bologna Declaration, Joint Declaration of the European Ministers of Education.

- The European Higher Education Area, 2001, Towards The European Higher Education Area, Communiqué of the meeting of European Ministers in charge of Higher Education in Prague

- The European Higher Education Area, 2003, Realising the European Higher Education Area, Communiqué of the Conference of Ministers responsible for Higher Education in Berlin

- Decision of Authorization Council, Decree No. 1, 15.02.2018, Available from: <https://eqe.ge/geo/decisions/ show/7780>

- Decision of Authorization Council, Decree No. 3, 15.02.2018, Available from: <https://eqe.ge/geo/decisions/ show/7784>

- Decision of Authorization Council, Decree No. 5, 22.02.2018, Available from: <https://eqe.ge/geo/decisions/ show/7812>

- Decision of Authorization Council, Decree No. 43, 28.06.2018, Available from: <https://eqe.ge/geo/decisions/ show/8256>

- Decision of Authorization Council, Decree No. 44, 28.06.2018, Available from: <https://eqe.ge/geo/decisions/ show/8258>

About the Author

Diana Lezhava is an Administrative Director and a researcher in the Higher Education Program at the Center for Social Sciences, Tbilisi, Georgia.

Rethinking Armenian Students’ Engagement in Quality Assurance: Perspectives for Meaningful Participation

By Edith Soghomonyan, National Erasmus+ Office Armenia, and Gohar Hovhannisyan, European Students' Union

DOI: 10.3929/ethz-b-000292932

Abstract

The article reports on the patchy development of Armenian students’ participation in the Quality Assurance (QA) system by focusing on the existing modes of engagement in QA and the barriers for meaningful student participation faced by challenging student representation. It provides insights into the existing QA framework in Armenia, student demographics within the Armenian HE landscape and recent politically charged developments that have stimulated an informal student movement to demand enhanced university quality. An EU-funded project encouraging Armenian students’ engagement in internal and external QA is also referenced with its relevant outcomes. The authors aim to illustrate that despite acclaimed progress in the development of formal structures for student engagement, students are still largely unaware and demotivated about their role in QA (Fedeli, 2018b), which leads to their token participation. The paper concludes that the perspectives for meaningful participation call for sustainable capacity building of students, recognition of their full membership in academic community and the constituency of student representation. Finally, it strongly recommends students’ inclusion in the policy dialogue and collaboration between all national and institutional stakeholders of QA.

Introduction

Student engagement in quality assurance (QA) has been recognized as one of the crucial components of institutional quality development in the making of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) (Scott, 2017). Within the popular student-centred rhetoric, the importance of European students’ participation in QA has been continuously promoted and, to some extent, even “standardized” by the Bologna Process (BP). By widening non-EU countries’ access to EHEA, these standards have outgrown their European context, providing further impetus for newcomers’ domestic higher education reforms. In 2005, Armenia was one of the 48 Bologna signatory countries that embarked on this reform path by redesigning its tertiary education in alignment with the European Standards and Guidelines (ESG) for QA (Gharibyan, 2017).

The country dwelled upon a tier step introduction and implementation of a comprehensive QA system for student-centred education. As a starting point, the National Centre for Professional Education Quality Assurance Foundation (ANQA) was established in 20081, and the two acting modes of External and Internal QA were introduced into the system of higher education (HE). As of now, the key role in developing regulatory standards belongs to ANQA, which implements QA in HE through its first pillar—institutional (mandatory) and programme (voluntary) accreditation. The primary purpose of accreditation, which is the focal point of External QA (EQA) in Armenia, is to ensure the overall high quality of tertiary education and to ensure an accredited university’s performance and integrity are recognized as effective by all its stakeholders: academia, students, employers, the government and the wider society.

The introduction of institutional Internal Quality Assurance (IQA) as the second pillar of the QA system aims at improving internal quality to match European quality standards. Following ESG recommendations, within the period 2010–2012, all higher education institutions (HEIs) have established institutional IQA units (ANQA, 2016) with a mission to support the formation of a quality culture via self-assessment reports, QA manuals, surveys, etc. These processes have been developed along with the growing recognition of students’ central position within the student-centred model of quality HE. How have the students been integrated into these quality processes? Has their participatory role had an impact on institutional quality improvement? To answer these questions, we need an overview of HE provisions for Armenian students.

A “Bird’s Eye View” on HE Provisions and Established Mechanisms of Student Participation in QA

According to recent national data, there are 23 public, 4 interstate and 26 private HEIs (Gharibyan, 2017), Officially, in 2017–2018, 92,558 students were registered in Armenian HEIs. Tuition fees vary per region, institution, level of education and specialization. The lowest yearly tuition fees for the bachelor’s level in the capital start from 720 EUR and can reach up to 1400 EUR (academic year 2017–2018)3. The fees increase yearly because of the annual decrease in student applications. Hence, despite a demographic decline in student population, HEIs meet most of their budgets at the expense of student fees. These factors affect the quality of education and suggest student ownership in the level of investment.

As tuition fee payers or scholarship holders, all students are full members of the academic community (Prague Communiqué, 2001), and their influence on and involvement in university structures and processes towards quality enhancement is crucial. In Armenia, student engagement in QA is endorsed by student experts’ pool—a group of students trained for mandatory institutional accreditation4, mainly pertaining to EQA. The accreditation panel usually includes one student who is enrolled in a subject relevant to the accreditation, has enough student experience, and is trained on accreditation/audit. ANQA recruits student experts by reaching out to university top management, Armenian National Students’ Association (ANSA) and other student-friendly platforms. It maintains the “Students’ Voice” 2–3 month-long training programme5 to equip student trainees with analytical skills for assessing self-evaluation activities of HEIs using defined quality criteria and standards and writing an audit report (Scott, 2017).

Participation in QA is a continuous process and cannot be limited to mere accreditation. The mechanisms of student participation in IQA processes are determined institutionally. They can be concluded with the following modes (Draft Law of the RA on HE, 2018):

- Participation in student and graduate satisfaction surveys

- Inclusion in the Academic Councils and QA Committees

- Representation in student self-government bodies (student councils, student scientific councils, etc.)

- Under the established institutional procedures, students participate in university self-assessment.

In contrast to European Standards and Guidelines (2015), which prescribes students’ active engagement in creating their own learning process (ESG, 2015, point 1.3), these modes suggest a rather restrictive framework of student participation. Moreover, such conceptualization of students’ modes of participation in IQA leaves limited space for institutional decision making on flexible implementation, monitoring and revision of QA policy (ibid, point 1.1). It can be concluded from the above that both external and internal QA provisions equip Armenian students with some participatory function. To what extent do these functions promote the meaningful involvement of students in all university governance structures?

External Support through Capacity Building: Identifying Existing Barriers and Questioning Student Awareness

Between 2011 and 2017, a notable number of international cooperation and EU funded projects6 were conducted to support the development of QA of HE. However, only one of them—TEMPUS ESPAQ7 project—has looked directly into student experiences and the mechanisms of their participation in EQA and IQA processes. It aimed to develop different tools and methodologies for better engagement of students by raising awareness on the importance of their voice within the academic community, building capacity, facilitating cooperation between all key stakeholders and by making targeted policy recommendations (Scott, 2017). As a final outcome of the project, an independent pool of student experts was established in 2017 on the basis of the Memorandum of Understanding signed by the MoES and ESPAQ project partners8. However, as of now, this pool has not been notably active in the field. Among the project deliverables is the comprehensive study on the state of art of student involvement in QA ‘‘[...] to investigate the current students’ perceptions and habitus regarding QA in Armenia.’’ (Fedeli, 2016b, p.5).

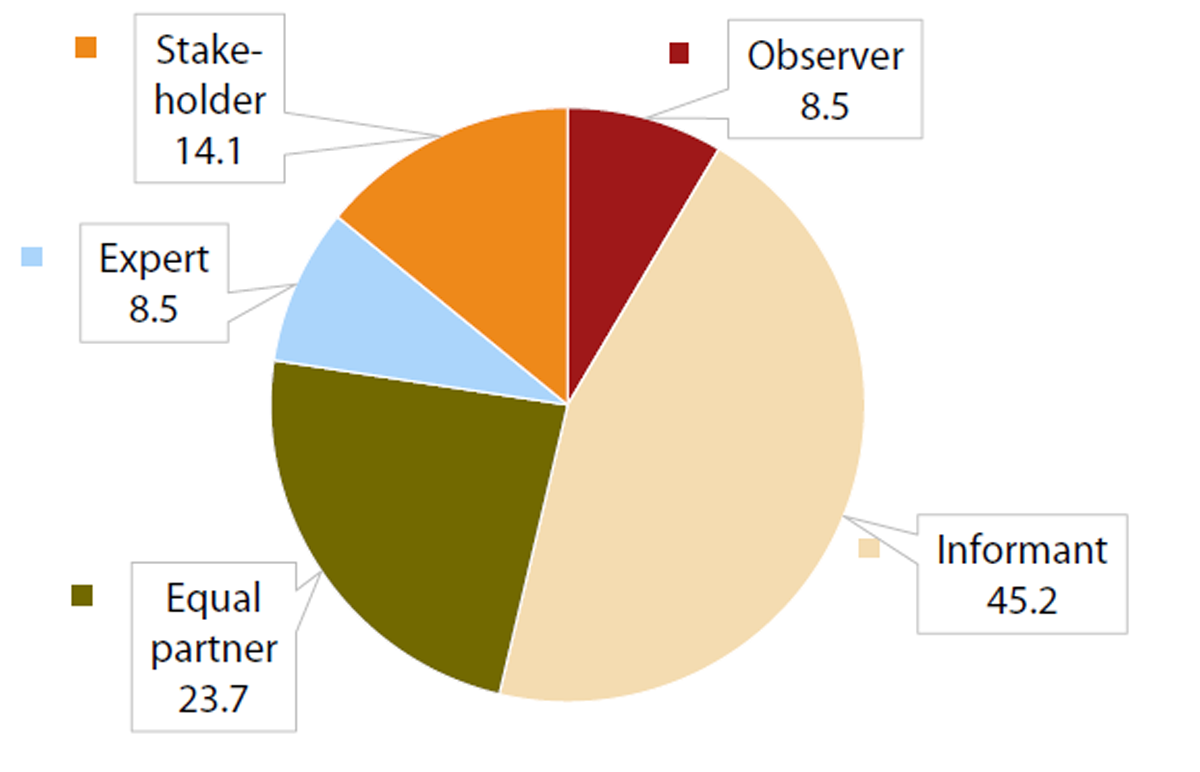

According to the figures of this study, 45.2% of all 176 student respondents assign the role of informants to students participating in the decision-making process of a QA expert panel (Figure 1) (ibid).

Only 23.7% of students see themselves as equal partners, 8.5% as experts and 14.1% as stakeholders. The remaining 8.5% are inclined to see themselves in the role of observers. Findings related to students’ direct involvement in IQA questionnaires are less dramatic. However, approximately 32% of the respondents perceive themselves as feedback providers to preset questionnaires. The other 54% lean to ‘‘more actively involve and negotiate the design of feedback questionnaires in close cooperation with the academic staff’’ (Fedeli, 2016b, p.23), and only 11% consider themselves as experts eager to design their own feedback questionnaires. These data suggest that notwithstanding institutionalized practices of students’ involvement in QA, despite students being the key source of university revenue, in Armenia, there are still certain barriers to meaningful student participation in the QA system, one example of which is token participation. Students themselves note the following barriers for their engagement (Fedeli, 2016b):

- lack of concreteness: involvement in QA is a formal statement that doesn’t result in a concrete establishment or in the desired changes;

- lack of information: ineffective communication flow between students and their representatives;

- lack of awareness: students and staff lack the needed competences to deal with QA;

- lack of reliability: students don’t use their voice to improve the system;

- lack of motivation: students don’t take advantage of their role in university bodies.

These barriers are derived from a number of national, institutional, individual and cultural factors. They weaken the understanding of students’ role in QA and deepen mistrust towards fair and legitimate representation of student bodies in Armenia. In this article, we focus on some of the most studied barriers.

Figure 1: What Role Would You Assign to the Participation of a Student in a Decision-Making QA Expert Panel/Committee?

Tokenistic Participation Resulting from Student Mistrust

As early as 2010, “Higher Education in Armenia” publication of the European Commission (EACEA, 2010) mentions the lack of students’ understanding of their role in the organization of education as one of the main obstacles to meaningful student engagement in QA. Another more recent critical study by Milovanovitch et al. (2016, p.137) indicates politicization and vertical management of HEIs as culprits of student inertia:

‘‘In most universities, there is no real student power [...] students have the opinion that their student representatives are instructed and directed by the university leadership or by a party.’’

By law, Armenian students represent a significant percentage of university governance bodies (Matei et al., 2013). Nevertheless, as with the case illustrated by the ESPAQ study, it is deemed to be a rather tokenistic representation. The symbolic nature of such participation is also supported by the lack of structured student representation on the national level of HE governance (Gajek & Hovhannisyan, 2017). Roots for this limited participation can be sought primarily in mistrust towards the constituency of students’ representative bodies and in the consequential lack of their capacity and interest to meaningfully engage in decision making and institutional quality enhancement processes. Hence, it can be concluded that in highly centralized governance, with no structured support to student bodies, the chances of meaningful student representation in formal governance are dim. In addition, inadequate awareness of quality culture and student-centred approaches creates a rather challenging environment for students’ full engagement in QA processes.

“YSU Restart”: Informal Student Movements as a Trigger of Change

Despite the aforementioned formal barriers, due to the informal student movement9 that kick-started in Armenia in autumn 2017, the country is currently seeing its’ students’ growing interest in taking stock for the quality of their education. At the beginning, the movement was socially oriented, expressed through various protests and sit-ins, which, according to Klemenčič (2015, p. 4), ‘‘are the most notable forms of student collective agency, and there are ample examples of students protesting against poor study conditions.’’ Initiated by a group of Yerevan State University (YSU) students, who established the “YSU Restart” student movement, the main objective was to draw attention to the key issues of the university from the poor quality of education to the lack of appropriate infrastructure and sanitary conditions for students. One of the leaders of this movement explained:

“[…] we have also discussed [...] the availability and accessibility of books, the student rights and the education quality. We believe that the time for reforms has come.” (ESU, 2018a).

The protests and sit-ins were attended by hundreds of students, and by March 2018, the initiative had grown into a movement with more campuses, universities and students joining. It can be claimed that the “Restart” movement is, in fact, the first large-scale student initiative to make an unprecedented claim for institutional accountability for the quality of education and infrastructure students receive after paying substantial tuition fees. These students have been the major driving force of the recent political developments in Armenia known as the “Velvet Revolution10”, ‘‘for no one has felt the effects of Armenia’s failed governance more viscerally than they’’ (Manukyan, 2018). Hence, we believe that the new political contexts conducive to active civic engagement of students can contribute to the overall improvement of QA in Armenian HE.

Conclusion

This brief review of less institutional and more informal student engagement in enhancing the quality of learning aimed to illustrate that meaningful participation requires a collective approach, and meaningful results necessitate urgent commitment from all HE stakeholders. In this article, we tried to argue that despite formal mechanisms for and capacity building of student experts in EQA and institutionalized modes of students’ representation in IQA, the lack of democratic student support structures (both national and institutional), low awareness of and tokenistic approach (of the students themselves) to participation in QA calls for a strong demand for policy incentives. The need should be addressed by encouraging more transparent and result-oriented QA processes and legally supporting independent student bodies as equal stakeholders in QA-related decision-making structures. Therefore, the future path and perspectives for meaningful student participation in QA depend on recognizing students as equal partners; strengthening the student body, including the newly created independent pool of student experts; and encouraging dialogue between all stakeholders of QA. On the one hand, the policy dialogue on students’ role in QA must include student national bodies. On the other hand, HEIs need to develop flexible pathways for engaging students in IQA and strengthening communication between involved stakeholders. The above example of “Restart” student movement illustrated that Armenian students’ sense of collective belonging and collective university identity can be self-cultivated through informal gatherings and movements. However, if Armenia wants student participation in QA to be manifested in a meaningful, organised and sustainable way, with a real and profound impact on system level, it needs to endorse and legitimize the genuine quality of participation through building students’ capacity to contribute to QA and supporting constituent student representation.

Notes

1 ANQA is the only national accrediting agency from the region that has full membership in the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) and is registered in the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR)

2 The decreasing student population due to growing emigration is the principle driver of change.

3 These numbers are derived from the authors’ comparative desk study of the websites of 5 public universities (Yerevan State University—<www.ysu.am>, Armenian State University of Economics—<www.asue.am>, National Polytechnic University of Armenia—<www.npua.am>, State Academy of Fine Arts— <www.yafa.am> and Yerevan Brusov State University of Languages and Social Sciences , where they extracted information on BA/BSc tuition fees for the academic year 2017–2018.

4 First-time students mentioned as participants in EQA in the “Guidelines, Criteria and Standards for QA in the Armenian tertiary education’’ (ANQA, 2011).

5 More information is available here: http://www.anqa.am/en/ students/#Partnerships

6 World Bank project ARQATA (<http://arqata.anqa.am> 2011–2014); Tempus projects DIUSAS (2010–2012); PICQA (2010–2013); TNE-QA, (2013–2016); GOVERN (2013– 2016); ALIGN (2013–2016)—<https://erasmusplus.am/ ongoing-and-finished-projects/>

7 Tempus ESPAQ “Enhancing Students’ Participation in Quality Assurance in Armenian Higher Education” project, 2014– 2017, <www.espaq.eu>

8 The Armenian National Students’ Union, as one of ESPAQ consortium partners, is responsible for the management and coordination of this pool.

9 The term “informal student movement” here refers to an independent and self-organized student community unconstrained by the formal establishments of student representative bodies (such as student unions or councils).

References

- Aerden, A., Comet Señal, N., Coulie, B., Zarina, I. 2017, ENQA Agency Review: National Centre for Professional Education Quality Assurance (ANQA), Available from: <http://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/External- Review-Report-ANQA_FINAL.pdf> [26 July 2018]

- ARMSTAT—Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia 2017, Statistical Yearbook of Armenia, Available from: <http://www.armstat.am/file/doc/99504493.pdf> [16 July 2018]

- Balasanyan, S., 2017, From pedagogy to quality: the Europeanised experience of higher education in post-Soviet Armenia, European Educational Research Journal, Vol 17, Issue 4, pp. 584–601

- Draft Law of the Republic of Armenia on Higher Education, 2018 (In Armenian), Available from: <https://www.e-draft.am/projects/588/about>, [30 July 2018]

- European Commission 2015, Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG), Brussels, Belgium.

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice 2018, The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Available from: <https://eacea. ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/sites/eurydice/files/bologna_internet_chapter_4_0.pdf> [29 July 2018]

- European Commission 2010, Higher Education in Armenia, Brussels: EACEA

- European Ministers in charge of Higher Education 2001, Towards the European Higher Education Area Prague Communiqué, Available from: <http://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/010519PRAGUE_COMMUNIQUE. pdf> [26 July 2018]

- European Students’ Union 2017, Guidebook for Improving Students’ Participation, Tempus ESPAQ “Enhancing Students’ Participation in Quality Assurance in Armenian Higher Education”, Available from: <https://oercommons. s3.amazonaws.com/media/editor/168210/ESPAQ_Guidebook.pdf> [28 July, 2015]

- European Students’ Union 2018a, Armenian Students fighting for a better life on campus, ESU, Available from: <https://www.esu-online.org/?news=armenian-students-fighting-better-campus> [29 July 2018]

- European Students’ Union 2018b, Bologna with Student Eyes 2018: The final countdown. Brussels: European Students’ Union (ESU).

- Fedeli, L. 2016a, Comparative Study of Students Involvement in Quality Assurance, Tempus ESPAQ “Enhancing Students’ Participation in Quality Assurance in Armenian Higher Education”, Available from: <http://espaq.eu/ images/documents/archive/publications/2016-01-27-Deliverable2_1-v2-en.pdf> [19 July, 2018]

- Fedeli, L. 2016b, State of art of students’ involvement in QA in Armenia, Tempus ESPAQ “Enhancing Students’ Participation in Quality Assurance in Armenian Higher Education”, Available from <http://espaq.eu/images/documents/ archive/publications/2016-04-12-deliverable-2_2-en.pdf> [28 July 2018]

- Gajek A. & Hovhannisyan G. 2017, ESPAQ Project as a case study of students’ empowerment in higher education governance, 12th European Quality Assurance Forum Responsible QA: Riga, Latvia, Available from: <http://www.eua. be/Libraries/EQAF-2017/p22_gajek_hovhannisyan.pdf?sfvrsn=0> [28 July 2018]

- Gharibyan, T. 2017, Armenian Higher Education in the European Higher Education Area, Inside Higher Ed, Available from: <https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/world-view/armenian-higher-education-european-higher-education-area> [16 July 2018]

- Keshishyan, A. 2018, The purpose of “YSU Restart” is to have a University, that is a bright spot of education, HETQ investigative journalists (in Armenian) Available from: <http://hetq.am/arm/news/86021/eph-restart-i-npatakn-e-unenal-eph-ory-krtakan-lusavor-mi-ket-klini.htm> [31 July, 2018]l

- Klemenčič M. 2015, Student Involvement in University Quality Enhancement. In: Huisman J., de Boer H., Dill D.D., Souto-Otero M. (eds) The Palgrave International Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance. Palgrave Macmillan, London

- Manukyan, S. 2018, Students Discuss Reforms for Armenia’s Broken Educational Institutions, The Armenian Weekly, Available from: <https://armenianweekly.com/2018/05/15/depoliticizing-of-armenias-universities/> [29 July 2018]

- Matei, L., Iwinska, I., Geven, K. 2013, Higher Education in Armenia Today: a focused review Report for the Open Society Foundation Armenia, CEU Higher Education Observatory, Budapest, Available from: <http://www.osf.am/ wp-content/uploads/2013/11/OSF_HE_report.pdf> [26 July 2018]

- Milovanovitch, M., Ceneric, I., Avetisyan, M. 2016, Strengthening integrity and fighting corruption in education: Armenia, Open Society Foundations Armenia, Available from <http://www.osf.am/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ Integrity-Report_ENG_PUBLISHED_16.01.2017.pdf> [12 July 2018]

- Ministry of Education and Science of RA 2018, Student population in higher and postgraduate education of RA in the academic year 2017–2018 (in Armenian), unpublished statistics

- National Center for Professional Education Quality Assurance Foundation (ANQA) 2016, Second System- Wide Analysis 2012–2015, Yerevan, Available from: <http://www.anqa.am/en/publications/second-system-wide-analysis-2012-2015/>, [19 July, 2018]

- Popovic, M. 2011, Student Participation in Higher Education Governance, General Report of a Bologna Seminar in Aghveran, Armenia, Available from: <http://www.aic.lv/bolona/2010_12/Sem_10_12/Armenia_Aghveran_ Final%20report.pdf> [26 July 2018]

- Scott, D. 2017, Students Handbook on Quality Assurance in Armenia, Tempus ESPAQ “Enhancing Students’ Participation in Quality Assurance in Armenian Higher Education”, Available from: <http://espaq.eu/en/archive/ publications> [12 July 2018]

- Topchyan, R., Grigoryan, K., Gyulazyan, V. 2017, MAHATMA Project as an Experience of Cluster Accreditation in Armenia and in Georgia, in “Crisis Management and Technology” Scientific and Scientific-Methodical Collected Articles, N11, ISN1829-2984, Yerevan, pp. 6–14, Available from: <http://www.anqa.am/en/publications/mahatma-project-as-an-experience-of-cluster-accreditation-in-armenia-and-in-georgia/> [26 July 2018]

- Tsaturyan, K., Fljyan, L., Gharibyan, T., Hayrapetyan M. 2017, Overview of the Higher Education: Armenia, EACEA, Available from: <https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/sites/eacea-site/files/countryfiches_armenia_2017.pdf>, [31 July, 2018]

- Vanyan I., Gevorgyan N., Marukyan M., Baghdasaryan A., Grigoryan A., Petrosyan M., Tanajyan K., Melkumyan M., Sahakyan L. 2016, Survey Data Analysis by ASPU, ASUE and NUACA. Comparative Study on Students Involvement in Quality Assurance, Tempus ESPAQ “Enhancing Students’ Participation in Quality Assurance in Armenian Higher Education”, Available from: <http://espaq.eu/images/documents/archive/publications/2016-04- 12-deliverable2_2-survey-data-en.pdf>, [12 July 2018]

About the Authors

Edith Soghomonyan is currently a Programme Officer at the National Erasmus+ Office in Armenia.

Gohar Hovhannisyan is an Executive Committee member of the European Students’ Union.