Securitizing Migration – Europe and the MENA Region

16 Aug 2012

By Mona Chalabi

Since 1945, Arab immigration has been a fact of European life. Indeed, some of these migrant paths have always been particularly deeply tread such as those between Algeria and France as well as Morocco and Spain. In the post-war period, there was a broad consensus among many Western European states that the recruitment of temporary foreign workers would benefit domestic labor markets. This began to change however in the external page1970scall_made when economic restructuring disproportionately affected Arab immigrants, many of whom were employed in those sectors where job loss was highest. Migrant workers, including those from Arab countries, were now subject to drastic restrictions which prevented them from travelling back and forth. Accordingly, the previously mobile male workers decided to settle permanently and many were joined by women and children as family reunification became an unintended consequence of Europe’s new restrictive policies. Immigration quickly became, and remains, a highly politicized subject.

The years since - particularly the 90s and early 00s - have been marked by concerns regarding differences between the identity of Arab immigrants and that of their host countries. Highly mediatized debates such as external pageJihad vs. McWorldcall_madeand external pageEurabiacall_maderaised questions about the feasibility of integrating Arab migrants into European countries. Today, the on-going global financial crisis and Arab uprisings have dramatically challenged these assumptions about migration to Europe and its implications for European security.

Post Financial Crisis

Five years ago, the Eurozone joined most of the international system in feeling the effects of the global credit crunch which, in turn, led to recession in many parts of the region. In a new era of austerity, an emphasis on the integration of Arab migrants (the obstacle to which is perceived to be largely about identity) has shifted towards an emphasis on the absorption of Arab migrants (the obstacle to which is perceived to be largely about economic capacity). The economic and social external pageindicatorscall_made used by the European Union (EU), for example, to analyze immigrant integration now emphasize employment, net income and property ownership.

This is not the only shift occurring in Europe’s political landscape. Terms such as ‘risk’, ‘threat’, ‘collapse’, ‘buffer zones’ and ‘losses’ - not to mention ‘securitisation’ - were once the vocabulary of defense officials and those employed in the field of ‘hard’ security. Today, they are also used by economic analysts to capture how national institutions have been severely destabilized as a result of the economic crisis. Accordingly, when the chances of inter-state conflict seem almost unthinkable, whereas the prospect of the collapse of the Euro warrants contingency measures, security in Europe is being redefined. Where Arab migration was once considered as a potential source of social tension, it is now instead being scrutinized for its economic implications.

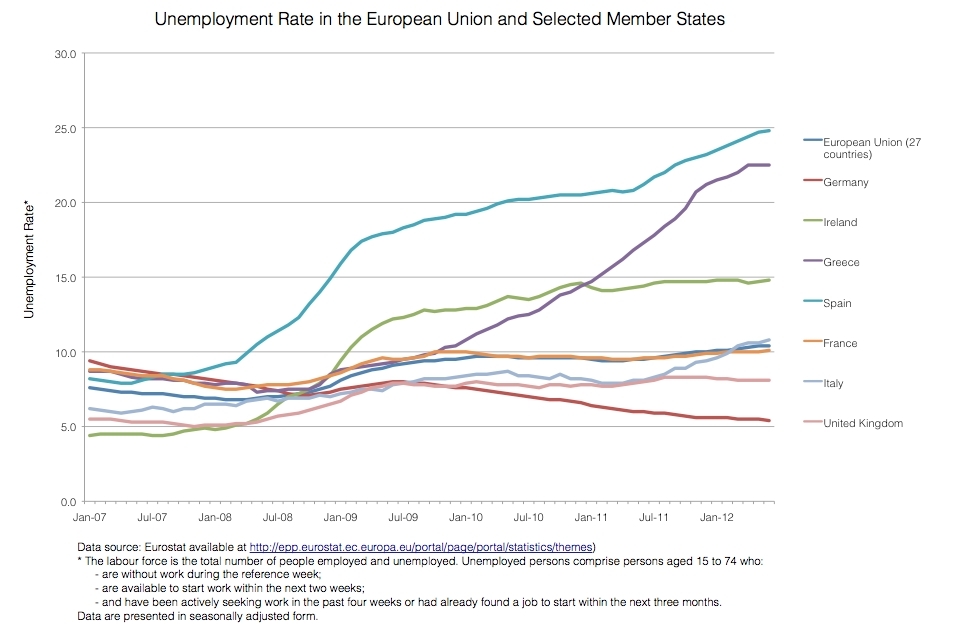

Though its causes may be global, by far the most obvious consequence of the crisis at a national level is unemployment. As the graph below demonstrates, unemployment in the EU has rocketed from a low of 6.9% in 2007 to 10.4% in June 2012.

(click image to enlarge)

In this economic context, European support for immigration appears to be on the decline. Politicians - particularly those witnessing the frighteningly fast external pagerevolving doorscall_made of European power since the onset of the crisis - are trying to gauge voter sentiment towards immigration. From former President Nicolas Sarkozy’s fury about a “ external pageflood of foreignerscall_made” to David Cameron’s pledges to cut net migration from external page239,000call_made to “ external pagetens of thousandscall_made”, immigration is fast becoming a central pillar of election campaigning. In part, mainstream politicians are attempting to stem support for the EU’s more extreme nationalist and populist parties, many of whom have risen from obscurity on a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment and declining economic conditions.

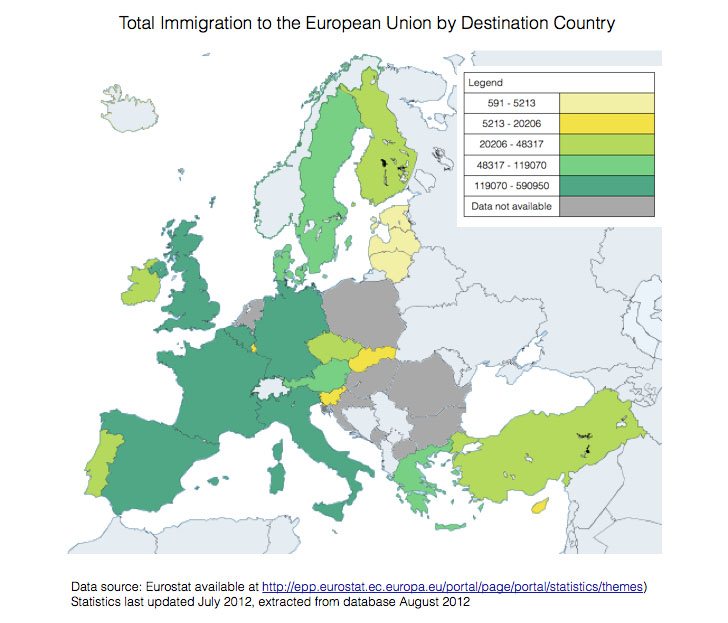

Yet, the graph also demonstrates the unevenness of the impact of the global financial crisis across the EU. Whereas 1 in 4 of the population is unemployed in Spain the statistic rises to in 1 in 20 in Germany. Crucially, these discrepancies are also visible in migration patterns. As the map below reveals, migration remains largely concentrated in the southernmost regions of the Eurozone, which have also witnessed some of the EU’s sharpest and hardest downturns.

(click image to enlarge)

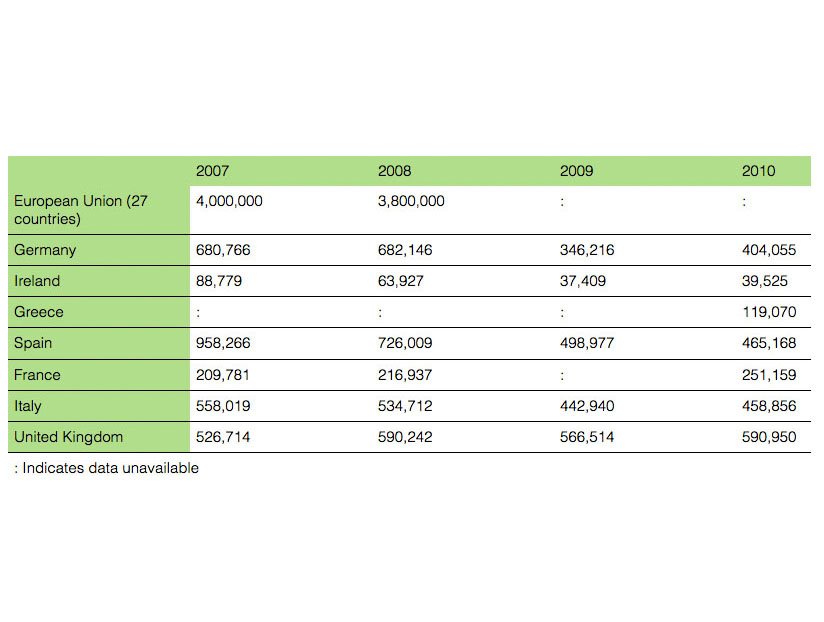

The figures displayed above fail however to demonstrate that migration trends have changed since the onset of the financial crisis. As migration is often motivated by hopes of economic advantage it is unsurprising that immigration to the Eurozone has declined. Member-states deeply affected by the crisis like Ireland and Spain have become far less attractive to immigrants and have seen numbers drop by 55% and 51% respectively from 2007 to 2010. Indeed, the financial crisis has also resulted in rising external pageemigrationcall_made from some EU countries.

(click image to see full table)

Post Arab Uprisings

Declining immigrant numbers did not, however, stop fears of a mass exodus from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) to the EU in the wake of the Arab uprisings. While publicly denouncing the previous regimes of Tunisia, Egypt and Libya and welcoming “ external pagesteps toward democracycall_made”, decision makers across the EU were also frightened by the prospect of a ‘external pagehuman tsunamicall_made’ that would tip the balance of security on Europe’s fragile economic shores. Indeed, ambivalence towards “external pagea changing neighborhoodcall_made” has arguably resulted in a lack of coherent policy responses to the uprisings.

The Lampedusa Case

The immigrant holding center on the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa only had capacity for 850 people when the Arab uprisings gathered pace in 2011. When 15,000 Tunisian and Egyptian immigrants arrived, local authorities were completely overwhelmed, prompting the United Nations (UN) to issue a external pagecrisis warningcall_made.

In February 2011, the Italian Minister for Home Affairs external pagestatedcall_made “we are facing a biblical exodus, and yet the European Union is doing nothing”. A month later, an Italian governor claimed “Lampedusa is swarming not with desperate refugees but with Tunisians fleeing a country where life has gotten back to normal and businesses have reopened”. Frustrated by a perceived lack of EU support, Italy began offering immigrants arriving to the island temporary residence permits that granted travel to other member states under the Schengen agreement. In the diplomatic fall out that followed, France blocked trains crossing the border in protest.

Lampedusa further heightened fears about Arab immigration after the uprisings, but these fears were not wholly warranted. Firstly, the UN had been issuing external pagestatements expressing concernscall_made about Lampedusa’s ability to meet the humanitarian needs of immigrants long before the Arab uprisings. Secondly, North African migrants were not the only ones attempting to reach Lampedusa, as demonstrated by the tragic incident when external page220 Somali, Eritrean and Ivoriancall_made refugees drowned en-route to the island.

Tensions within the EU nevertheless remain as southern member-states feel that they are shouldering a disproportionate amount of responsibility for immigration security. The functioning of the Schengen system (which allows passport-free travel in most of the EU) is dependent on mutual trust, the absence of which could spell disaster for EU border security.

Accordingly, the Lampedusa case may be regarded as symptomatic of an excessive, albeit understandable, perception of the security challenges posed by Arab migration since the uprisings began. While EU leaders desperately continue in their attempts to remain upbeat about the financial crisis, they have been overly pessimistic about the domestic implications of the Arab revolutions.

The latest statistics to come from the EU show that the number of Tunisians seeking asylum dropped by 3,000 from the first quarter of this year compared to the first quarter of 2011. Though it is true that the number of Syrian applications for asylum has risen by around 1,500 in the same period, the Tunisian case suggests that these rates are only sustained if political change at home remains elusive. It is also important to remember that of the external pagetwenty main citizenshipscall_made that apply for asylum in the EU, Arab countries only figure in 5th, 6th and 17th place (Iraq, Syria and Algeria respectively) with Afghanistan remaining in the top position. Fears about mass migration after political upheaval or, as in the case of Syria, humanitarian catastrophe, miss another crucial phenomenon. The most vulnerable are often those that cannot move at all. Involuntary immobility can slow migration flows to Europe even in extreme crises in the MENA region. In short, the Arab revolutions external pagedid not resultcall_made in the enormous acceleration of migration to the EU that many had predicted.

This is not to say that the Arab revolutions will have no impact on European migration and security. Arab immigrants to the EU may go back to countries where, due to regime change, they no longer fear persecution - so called ‘returnees’. Europe is the single largest destination for first-generation Arab emigrants, and hosts external page59%call_made of all such emigrants worldwide (4,897,462 out of 8,347,869). Once back in their country of origin, these returnees are not only likely to stop contributing to EU economies but may also stop crucial remittance flows which are higher than domestic salaries.

Inter vs. Intra

Debates about inter-regional migration, though important, fail to capture the crucial dynamics taking place within the EU and MENA region. Of external page13 millioncall_madeArab migrants in the world, 5.8 million reside in Arab countries. This migration represents an important source of financial and human capital within the region, and is likely to become all the more important in the reconstruction that lies ahead of countries such as Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. Remittances are also crucial for the economic functioning of the MENA region. Money sent by migrants to Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon from other Arab countries is external page40% to 190%call_madehigher than trade revenues between these and other Arab countries.

Meanwhile, in Europe, new dynamics within the region are causing some to raise questions about the relationship between migration and security. When Norwegian Anders Breivik killed 77 people in his native home in July 2011, he also published ‘ external page2083: A European Declaration of Independencecall_made’, a manifesto in which he blamed immigration and ‘Islamisation’ for many of the country's problems, asserting the “need to deprive Arabs and Muslims”. The Norway attacks made real the frightening possibility that immigration can increase external pagehatredcall_made as well as the security threat posed by domestic terrorism.

Future Forecasts

Private security companies (PSCs) are external pageincreasingly responsiblecall_made for the protection of the EU’s ports, airports, military and nuclear facilities and even provide security in areas previously considered the domain of police and intelligence services. Migration, as a high-priority on the security agenda, is not exempt from this privatization. As a result, PSCs are becoming increasingly involved in surveillance and border control. Securing Europe’s borders will however require greater emphasis on the push factors rather than the pull ones drawing Arabs to the region. Though these measures may be more effective for security, they also require more time and more money, something today’s European governments do not have in abundant supply.

Though the phenomenon, the paths followed and even, in some cases, the scale of Arab migration to Europe may not be new, the economic context and security paradigm in which it is occurring very much is. Just as European governments dramatically changed their immigration policies in the 1970s, contemporary economic concerns are spurring new debates about how welcome Arab migrants across the Eurozone. Currently, Europe is defined more by austerity than rising defense expenditure and military operations beyond the European heartland. So when jobs are at stake, claims that immigration threatens national unity, national sovereignty or national identity seem convoluted by contrast. The onus has, therefore, shifted on Arab immigrants to the EU from proving that they pose no terrorist threat to proving that they pose no economic threat.

Europe’s cleavages around identity are not about Islam and Christianity or religion and secularism - they are about the haves and the have-nots, the employed and the unemployed. It is not just economics that is becoming securitized - the notion of security is becoming increasingly economised. But perceptions about immigration might still change. With ageing European workforces and Arab youth continuing to swell, it is not inconceivable that one day, the absence of Arab immigration will be considered a greater threat to European security than its presence.