Human Security Report 2012, Chapter 5: State-Based Armed Conflict

24 Dec 2012

Editor's Note: This week the ISN takes the opportunity to highlight the comprehensive and scholarly insights provided by the 2012 Human Security Report. In particular, we focus on Part II of the report ("Trends in Human Insecurity"), which traces the incidence and severity of armed conflicts and other forms of violence at the regional and global levels. (The forms of violence include state-based conflicts, persistent armed conflicts, non-state armed conflicts and deadly assaults on civilians.)

The particular virtue of the 2012 report is that it debunks the conventional wisdom on a number of significant points. Among its conclusions are that military interventions in appear to increase death tolls in civil wars; that peace negotiations are in fact highly effective; that conflicts between non-state actors and one-sided violence against civilians have not increased over the past two decades; and that the number of conflicts worldwide appears to be stabilizing, despite significant year-to-year fluctuations. You can find the full contents of the 2012 Human Security Report external pageherecall_made, along with links to previous reports.

Our focus today is on Chapter 5 of the HSR, which examines global trends in state-based armed conflicts. The text not only defines such conflicts as those in which at least one of the belligerent parties is a legally recognized state, it also distinguishes between four types of these conflicts – extra-state conflicts, intra-state conflicts, internationalized intra-state conflicts, and inter-state conflicts. With these definitions in hand, the chapter then considers the relationship between each type of conflict and battle-related deaths. Overall, the data shows that while Africa remains a hotbed of conflict in general, Central and South Asia now has the highest number of battle-related deaths.

The chapter further reveals that the deadliest conflicts are those where external military forces interject themselves into civil wars. Indeed, these internationalized intra-state conflicts are, on average, twice as deadly as intra-state conflicts where no military intervention occurs. And what are we to conclude from this data? Well, with interventions comes the increased risk of conflict escalation, which means that even humanitarian military interventions may not be helpful. On the contrary, one-sided support for rebel groups actually correlates with intensified and prolonged conflicts.

Chapter 5: State-Based Armed Conflict

In this chapter, we analyze trends in the number and deadliness of state-based armed conflicts—those in which at least one of the warring parties is a government. We show how the geographic locale of the deadliest wars has shifted over time. In the first three decades that followed the end of World War II, most of the world’s battle deaths were in East and Southeast Asia and Oceania. In the 1980s, the Middle East and North Africa was the most violent region; in the 1990s, sub-Saharan Africa. By the middle of the new millennium, Central and South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa had become the world’s deadliest regions. Most recently, the deadliest conflicts in the world are concentrated in these two regions, notably the wars in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq.

Finally, we examine the complicated phenomenon of internationalized intrastate conflicts—civil wars in which external military forces intervene and fight in support of at least one of the warring sides. These conflicts include many of the wars involving major powers that have dominated the media headlines for decades—the Vietnam War, the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, the civil war in Iraq following the invasion in 2003, and the current conflict in Afghanistan.

We find that these wars are consistently deadlier than civil wars in which there is no external military intervention. Given the large numbers of troops and heavy conventional weapons that major powers can bring to civil-war battlefields, this is perhaps not surprising. What is surprising is that civil wars in which there are military interventions by minor powers can be as deadly as those in which major powers are involved.

Global Trends in State-Based Armed Conflict

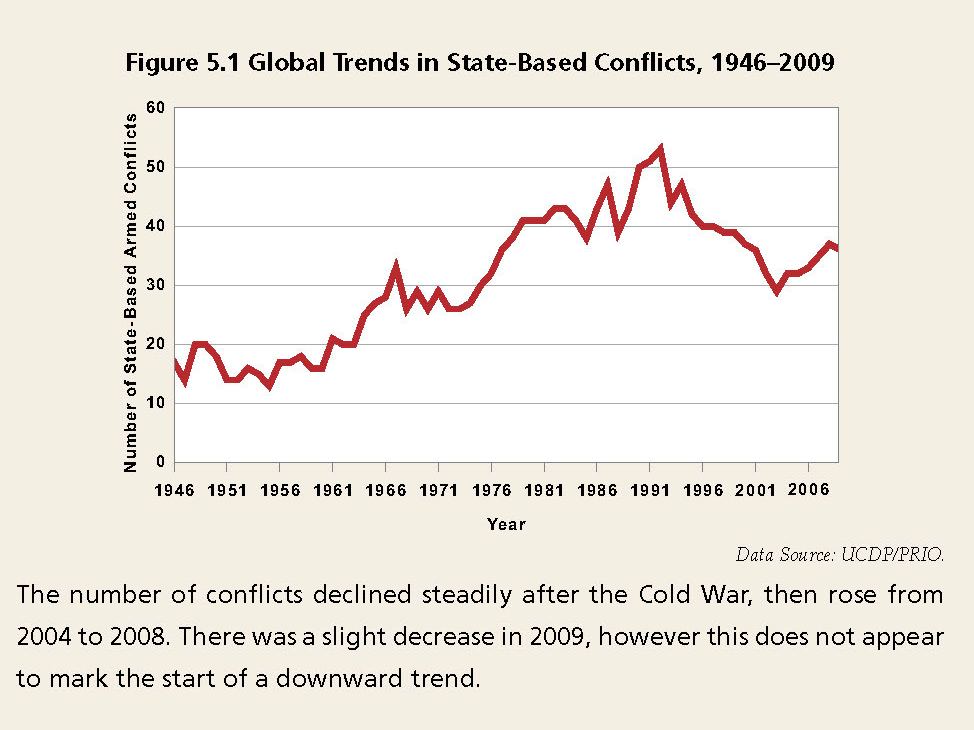

The last Human Security Report noted that the number of state-based armed conflicts rose by 25 percent between 2004 and 2008. While this was a significant increase, and clearly a source of concern, we cautioned against interpreting this five-year increase as a long-term trend towards an increased incidence of warfare around the world.

As Figure 5.1 below demonstrates, the number of conflicts in 2009 was a third lower, at 36, than in the peak year of 1992. The latest data, which we are currently analyzing for the next Human Security Reports, show that the number of conflicts appears to be stabilizing roughly at this level—i.e., between 30 and 40 active conflicts per year—despite significant year-to-year fluctuations.

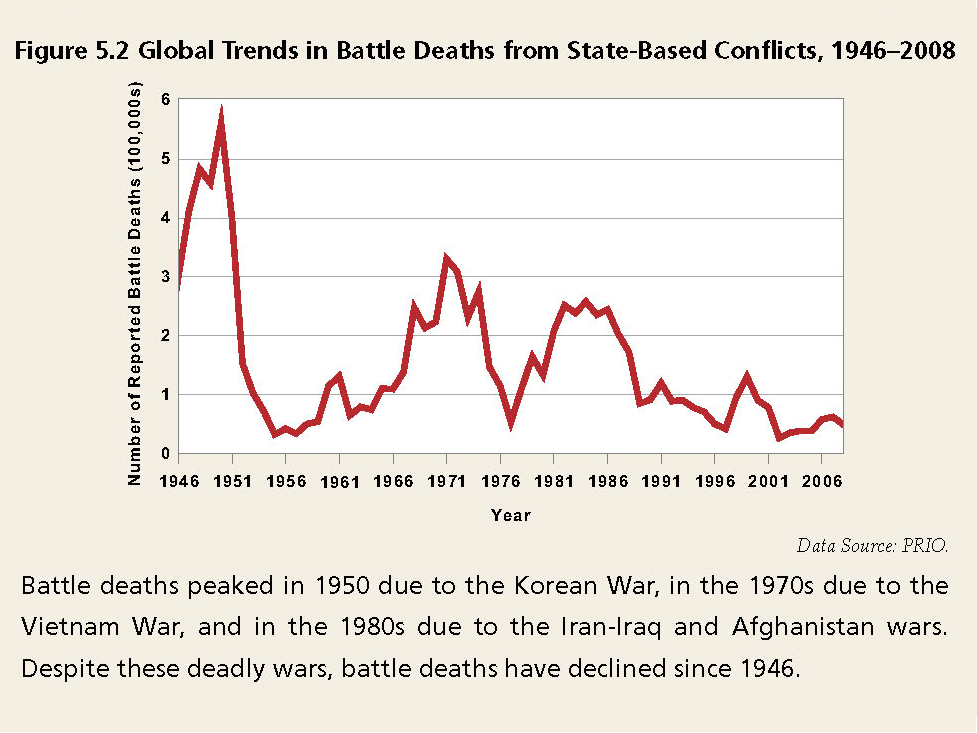

Battle deaths also increased by around a third from 2005 to 2008. But this increase should be seen in the context of the dramatic, decline in battle deaths over the past 60-plus years, shown in Figure 5.2. The average number of battle deaths per conflict in the post-Cold War period3 is some 76 percent lower than the average during the Cold War period.

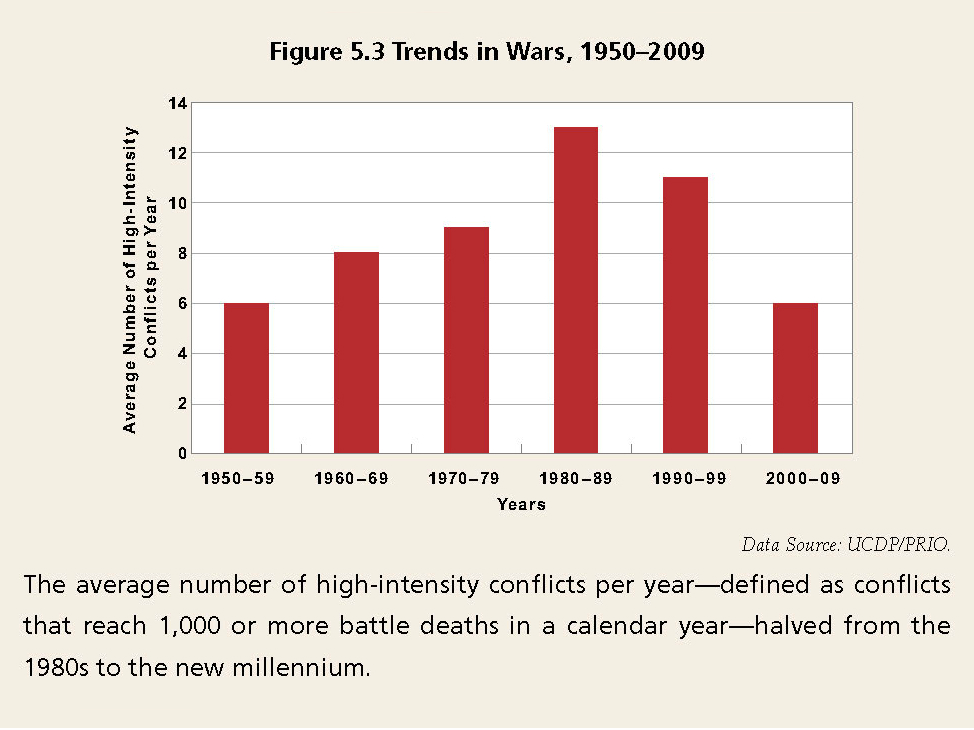

A large part of this long-term, but uneven, decline in battle deaths has been a result of the reduction in the number of high-intensity conflicts, counted as wars in years when they cause at least 1,000 battle deaths. As shown in Figure 5.3, in the new millennium the average number of wars being fought each year was just over half that in the 1990s.

Wars also make up a decreasing share of all conflicts. During the Cold War period—from 1950 to the end of the 1980s—31 percent of conflict years resulted in at least 1,000 battle deaths. That figure dropped to 25 percent in the 1990s, and even further to 19 percent in the new millennium.

The Deadliest Conflicts

In 2009 the three deadliest conflicts in the world were all in Central and South Asia—in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

There were just three high-intensity conflicts outside of Central and South Asia in 2009: in Iraq, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where Rwandan and Congolese forces battled the Democratic Liberation Forces of Rwanda (FDLR).

Of these six high-intensity conflicts, those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, and the DRC are internationalized intrastate conflicts. This type of conflict, as we explain later, tends to be considerably deadlier than civil wars in which there is no military intervention by external powers.

Four of 2009’s six most deadly conflicts, those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Somalia, are associated with international and local campaigns against Islamist groups. The security implications of this association were discussed in the last Human Security Report.

Regional Trends in State-Based Armed Conflict

Since the end of World War II, the location of the world’s deadliest conflicts has shifted repeatedly.

From 1946 to the end of the 1970s, East and Southeast Asia and Oceania was by far the deadliest region in the world, with most of the deaths being caused by the Chinese Civil War, the Korean War and the wars in Indochina. But, as we demonstrated in the last Human Security Report, with the effective ending of foreign military intervention (mostly by the US and China), the region’s major wars were over by the early 1980s and battle-death tolls declined steeply. Since the end of the Cold War, East and Southeast Asia and Oceania has suffered fewer battle deaths than any other region.

In the early 1980s, the Middle East and North Africa became the deadliest region in the world, with the war between Iran and Iraq alone causing hundreds of thousands of battle deaths. But in the late 1980s, death tolls in the region declined sharply, driving the global death toll down in the process.

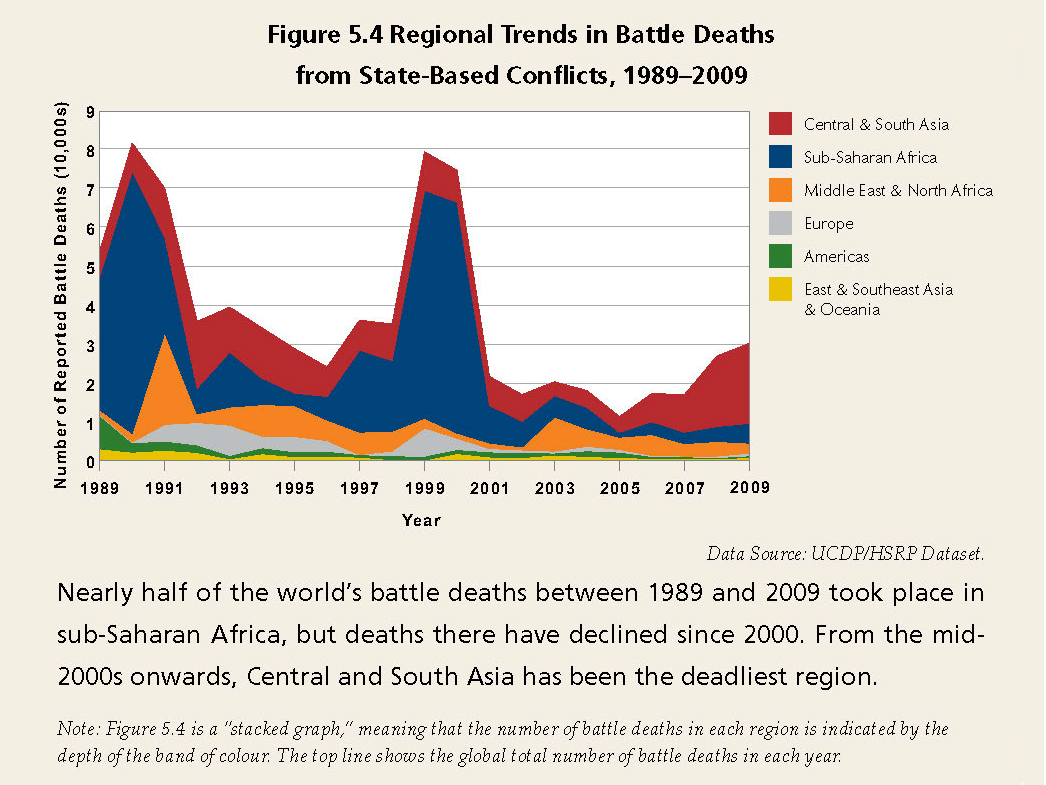

Half of the World’s Battle Deaths in the Post-Cold War Period Have Occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa

The battle-death toll in sub-Saharan Africa declined in the late 1980s, but in the second half of the 1990s it increased again—this time dramatically. This increase meant that sub-Saharan Africa was by far the deadliest region in the world in the 1990s. And as Figure 5.4 indicates, nearly half of the world’s state-based battle deaths between 1989 and 2009 were caused by wars in sub-Saharan Africa, most of them in the 1990s.

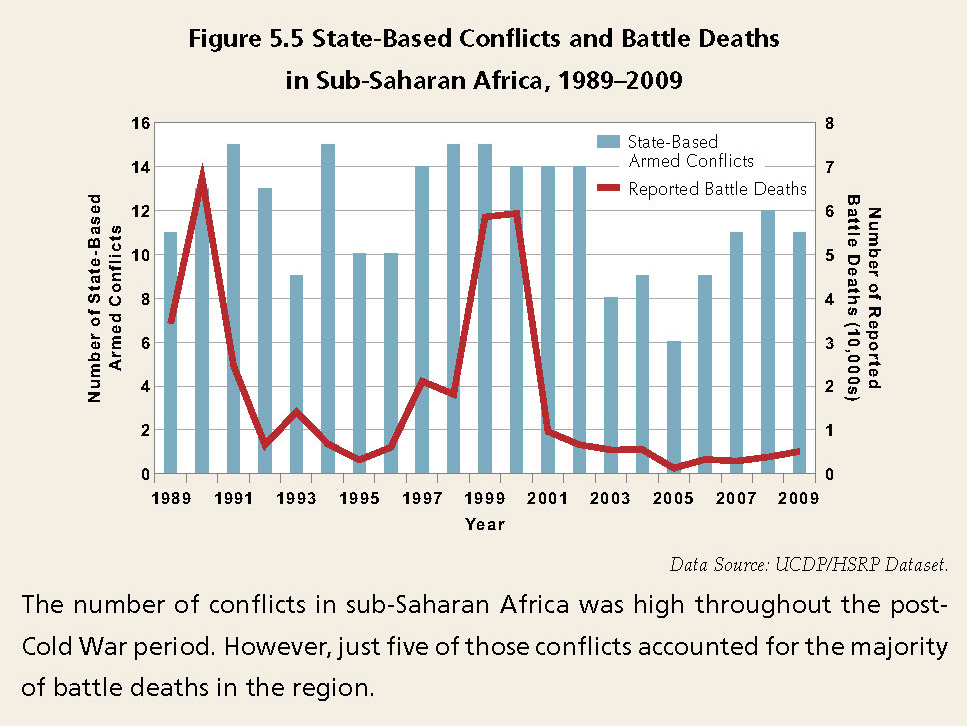

But in the new millennium there was another radical change as the number of people being killed in state-based conflicts across the region dropped dramatically. While the number of conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa has remained high, as Figure 5.5 demonstrates, the average number of battle deaths per conflict in the region has declined by 90 percent since 2000.

Sub-Saharan Africa has been by far the most conflict-prone region in the post-Cold War years, with nearly a third of the world’s total conflicts.

However, over half of the region’s battle-death toll has been due to just five conflicts, each of which caused at least 10,000 battle deaths in a calendar year at some stage in the conflict. Two of these wars were civil conflicts in Ethiopia. There was a single international conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and civil wars in Angola and the Republic of Congo (sometimes referred to as “Congo-Brazzaville”) that also exceeded 10,000 reported battle deaths in a year. Since the end of the Cold War, only one conflict outside sub-Saharan Africa has reached this level of intensity in at least one year: the war following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1991.

None of these conflicts have been active since 2002, however, and their ending has made a major contribution to the decline in global death tolls in the new millennium.

The list of the deadliest cases of organized violence also includes the 1994 Rwandan genocide and the violence in the DRC (sometimes referred to as “Congo-Kinshasa”) during the late 1990s and early 2000s, the latter of which has been described as “the world’s deadliest conflict since World War II.” In these cases, however, the majority of deaths resulted from one-sided attacks against civilians. Data on one-sided violence are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8 of this Report.

Central and South Asia Is Currently the World’s Deadliest Region

In the mid-2000s, death tolls due to conflicts in Central and South Asia and in the Middle East and North Africa increased relative to all other regions. As the battle-death toll in Iraq decreased in 2007, however, Central and South Asia has clearly become the world’s deadliest region.

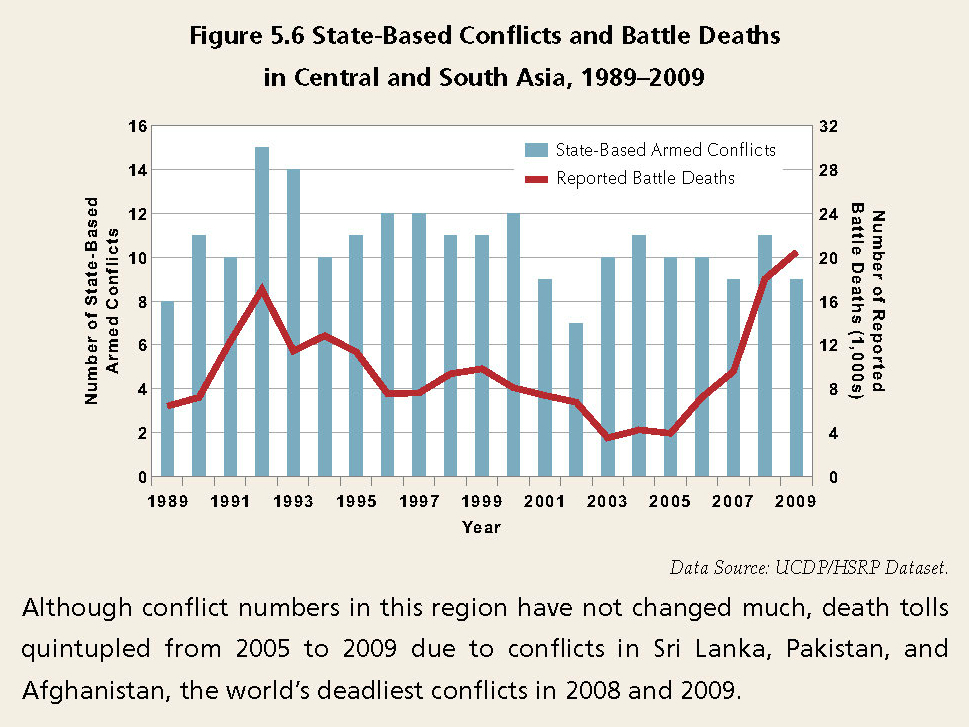

Recently, death tolls in Central and South Asia have escalated significantly, more than quintupling between 2005 and 2009, as shown in Figure 5.6.

In 2009 Central and South Asia alone accounted for two-thirds of the world’s total battle deaths from state-based armed conflict. The region had four times as many battle deaths as the next deadliest region, sub-Saharan Africa.

The fact that the number of armed conflicts in the region has remained fairly stable while the number of battle deaths has increased dramatically means that, on average, these conflicts are becoming deadlier. But this higher average is driven by just three conflicts. The wars in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Afghanistan were the three deadliest conflicts in the world both in 2008 and, as noted earlier, in 2009.

In 2009 the government of Sri Lanka decisively defeated the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and there have been no battle deaths associated with this conflict since mid- 2009. However, the other two conflicts, both associated with international and local campaigns against Islamist groups, show no signs of abating.

While these conflicts are currently the world’s deadliest, they cost far fewer lives than the deadliest conflicts in previous decades. For example, UCDP researchers estimate that the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea had a battle-death toll of nearly 50,000 in 1999 alone. In Sri Lanka it took some 18 years to reach a comparable cumulative death toll.

The Deadly Impact of Military Interventions

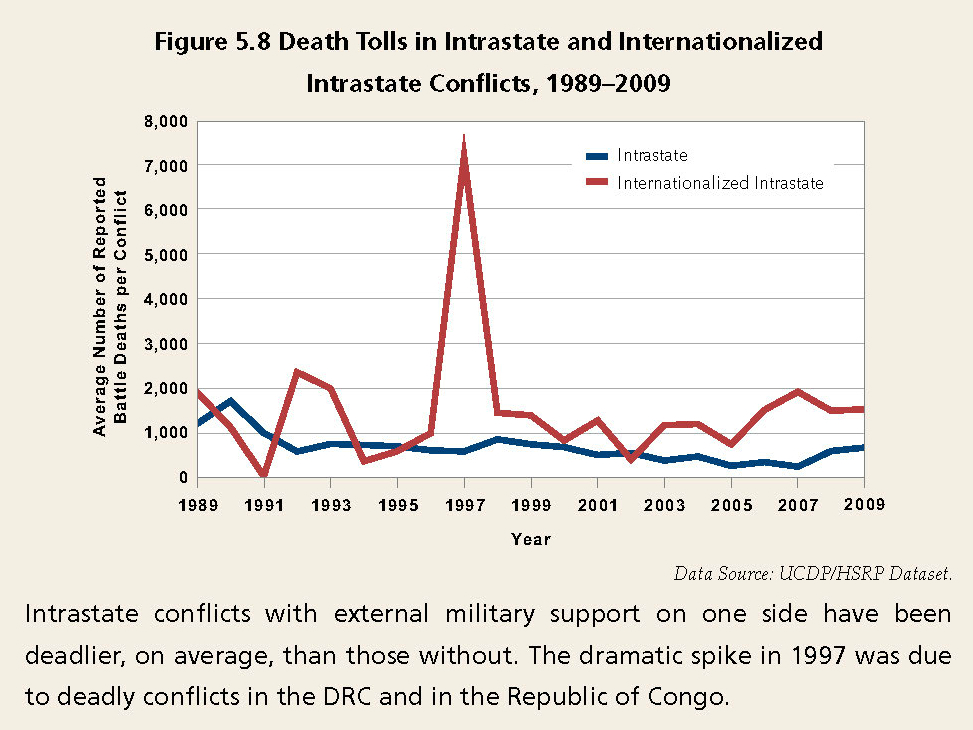

Many of the deadliest conflicts of the past two decades have involved external military forces fighting in civil wars. These internationalized intrastate conflicts are, on average, twice as deadly as intrastate conflicts where there is no military intervention.

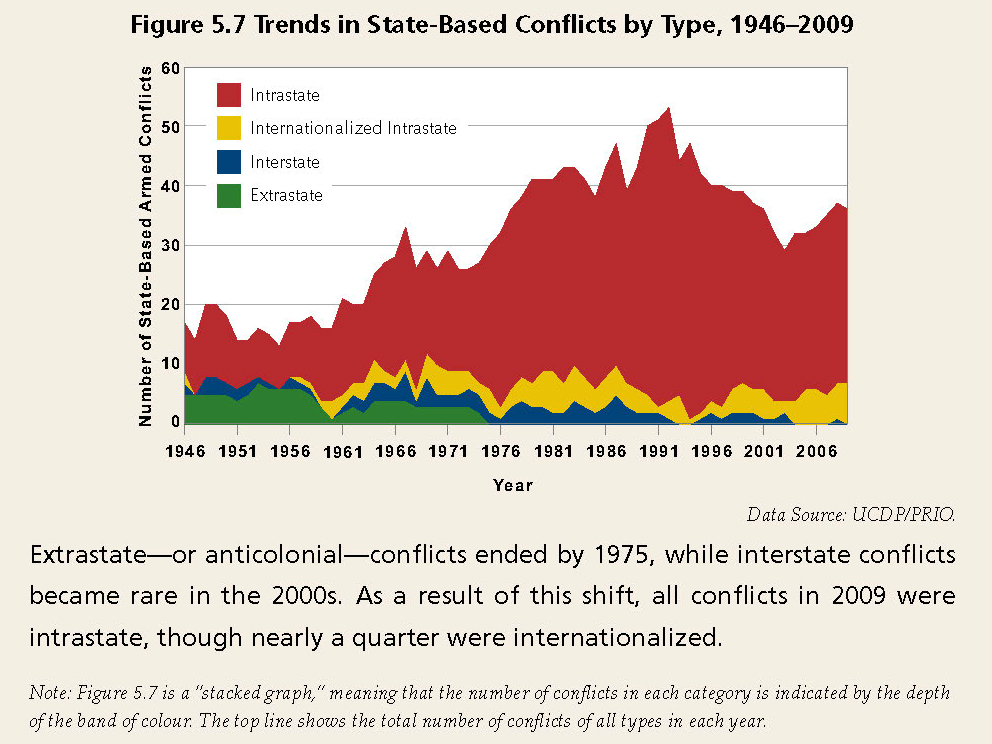

Interstate wars tend to have far higher battle-death tolls than civil wars with or without external military support, but as shown in Figure 5.7, conflicts between states have become extraordinarily rare. Since the end of the Cold War there have been three times as many internationalized intrastate conflicts as interstate conflicts.

Internationalized intrastate conflicts are a type of civil conflict in which the military forces of one or more external governments fight in support of one of the warring parties. This includes so-called humanitarian interventions if external military forces officially take sides and support a party to the conflict with troops. However, the definition does not include most peacekeeping missions, which are usually deployed to support negotiated settlements—and sometimes to help protect the peace against spoilers—but not to further the goals of a combatant.

States intervene militarily in civil conflicts in other countries for a variety of reasons. They may send forces to protect political or ideological interests, as was the case in the so called proxy wars of the Cold War era, or in response to humanitarian crises. Intervening states often have a complex combination of motivating factors, many of which may remain unstated. Our data do not provide information on these motivations but rather enable us to focus on the common characteristic of these conflicts: the presence of external military forces supporting at least one of the warring sides.

The highest-profile internationalized intrastate conflict currently is in Afghanistan, where the United States and its allies intervened on behalf of the Northern Alliance and now support the current government against the Taliban. The US-led involvement in Iraq started as an interstate war with the foreign forces fighting to end Saddam Hussein’s regime, but in 2004 the conflict shifted to a civil conflict in which the United States and its allies are militarily supporting the current government in its fight against rebel forces. Earlier examples of internationalized intrastate conflicts include the American intervention in South Vietnam in the 1960s and early 1970s and the Cuban presence in Angola in the 1970s and 1980s. France’s reinstatement of Léon M’ba as president of Gabon in 1964 was a smaller-scale internationalized intrastate conflict.

As the Cuban example shows, intervening countries can be non-major powers. North and South Vietnam (and later the Socialist Republic of Vietnam) played a major role in the Cambodian civil war throughout the 1970s and 1980s, while the armed forces of a major power, the US, were also involved. In the DRC the armies of several neighbouring countries fought in the civil war in the late 1990s and early 2000s without the presence of a major power.

As we will show in the following section, civil wars with foreign military support differ from other intrastate conflicts in a number of ways. Most notably, they are on average twice as deadly as conflicts in which no external powers are involved.

Intervention is Associated with Intensified and Prolonged Conflict

The trend data on internationalized intrastate conflicts show a strong positive correlation between external involvement in a conflict and that conflict’s battle-death toll, but this does not necessarily mean that the former caused the latter. The involvement of foreign combat troops and their weaponry in a civil war clearly has the potential to increase fatalities, but it may also be the case that foreign military support is more likely in conflicts that are already deadly.

The internationalized intrastate conflict in Iraq from 2004 to 2009 resulted in much higher battle-death tolls than any previous civil conflict in Iraq. In this conflict there is no doubt that the intervention was one of the major drivers of the huge death toll in the country. In other cases the pre-existing level of organized violence prompted the intervention that eventually stopped the fighting. Cases in point are the intervention of the US-led coalition in Kosovo in 1999 and the UK deployment of combat troops in Sierra Leone in 2000.

Surprisingly little systematic research has been done on the impact of external military support on conflict intensity. The limited findings so far provide little more than confirmation that external support is usually associated with high battle-death tolls, but quantitative analyses tend not to draw strong conclusions about causality.

Bethany Lacina, of the University of Rochester, finds that “[a] strong predictor that a civil war will be severe is the availability of foreign assistance to the combatants”—but her findings do not include an analysis of external military support in civil conflicts since the end of the Cold War. More recently, Kristine Eck, of Uppsala University, has found that the risk of conflict escalation—i.e., of higher death tolls— “increases by 192 percent if an external state intervenes militarily on the side of the rebels,” suggesting that this is because “obtaining troops and military resources from an external state” increases the “strength of the rebel organization.”

A number of researchers have examined the impact of external military support on the duration of conflict. Patrick Regan, of Binghamton University, who has done extensive research on different types of intervention, finds for example that “longer running conflicts tend to have more outside interventions.” But again, he notes that the research design of his study “cannot discriminate between the cause and effect.”

Some researchers argue that a one-sided intervention may increase the probability of victory for the warring party that receives the support and that this will shorten the conflict, but this claim is contested. Most agree that intervention leading to a balance of power between the warring parties is likely to prolong conflicts since neither side will have the forces necessary to defeat the other.

David Cunningham, of the University of Maryland, offers a somewhat different perspective, finding that the effect of external military interventions on conflict duration results from cases “in which the intervener has an independent agenda.” He argues that if there are separate agendas to be satisfied, the conflict will consequently be more difficult to settle.

Cunningham uses the example of South African and Cuban involvement in Angola’s civil war to illustrate how the presence of an external party can be an important obstacle to peace: with the winding down of the Cold War in the late 1980s, the political imperatives that had led South Africa to support the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) rebels and the Cuban government to support the left-oriented Angolan government lost their salience. Following an agreement in 1988, Cuban and South African forces withdrew. As Cunningham notes, this “paved the way for an internal peace agreement in Angola in 1991, albeit one that broke down a few years later.”

In December 2011 UCDP released a new dataset that provides more information on the involvement of foreign powers in wars. This includes the provision of both military and economic assistance by external actors. UCDP’s Therese Pettersson reviewed the new data, and preliminary findings “suggest that there is a positive relationship between external support and conflict intensity.”

Are Internationalized Intrastate Conflicts a Growing Threat?

Many scholars see military intervention in civil wars as a phenomenon associated primarily with the security politics of the Cold War. Bethany Lacina, for example, examines the impact of military assistance on conflict severity by comparing the death tolls of conflicts that started during the Cold War with those that started subsequently. She finds that conflicts that started during the Cold War had 1.8 times as many battle deaths as compared to the post-Cold War era. This makes intuitive sense: the high-stakes geopolitics of the Cold War drove many proxy wars—conflicts in which the US and the Soviet Union (or their allies) supported warring parties in the developing world. Support related to the ideology of the Cold War, which was often associated with extremely high death tolls, ended with the Cold War.

But while this might suggest that internationalized intrastate conflict numbers should have declined in the aftermath of the Cold War, the reverse has been true. The number of foreign military interventions in civil wars over the past two decades has actually increased, while the number of intrastate conflicts with no such intervention has decreased substantially. In the new millennium the number of conflicts in which external forces have intervened militarily is 70 percent higher than in the 1980s, the last decade of the Cold War. Therese Pettersson, using UCDP’s new data on external support, finds that the proportion of “active conflicts with external troop involvement” has gone from an average of 12 percent during the Cold War, to 7 percent in the 1990s, and up to 16 percent in the new millennium. If sustained, the rise in both the number and percentage of conflicts with external military intervention in recent years is a cause for concern.

As the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts increased over the past two decades, their average deadliness showed no discernible upward or downward trend. As Figure 5.8 demonstrates, internationalized intrastate conflicts have remained, on average, deadlier than other intrastate conflicts throughout most of the post-Cold War period. The difference peaks in 1997, a year in which external military support was recorded in only two intrastate conflicts. The civil wars in the DRC (“Congo-Kinshasa”) and in the neighbouring Republic of Congo (“Congo-Brazzaville”) each resulted in several thousands of battle deaths that year.

While there are civil conflicts with no foreign military support that are quite deadly, this analysis shows that, on average, conflicts that do involve external armed forces tend to be deadlier. The number of these conflicts, and the proportion of all armed conflicts that involve foreign military support, appears to be increasing. Even though the limited evidence available does not prove that military intervention causes deadlier conflicts—foreign militaries may be more likely to intervene in already deadly wars—it does suggest that a significant risk of escalation may be associated with intervention on behalf of a party to a conflict.

The Surprising Deadliness of Minor Power Intervention

Since the end of World War II, France, the UK, the US, and Russia (USSR) have each shown the ability to independently project power over significant distances. These four countries, which here we consider the major powers, have repeatedly dispatched military forces overseas to assist governments or rebels in fighting civil wars around the world. Some of these interventions—such as those by the US in Vietnam and the Soviets in Afghanistan—have been associated with hundreds of thousands of battle deaths.

It is not surprising that major power interventions, which add highly trained troops and sophisticated weapons systems into ongoing civil wars, are sometimes associated with high battle-death tolls. What is surprising is that military interventions by minor powers are, in many cases, associated with battle-death tolls that are just as high.

For example, the internationalized intrastate conflict in Angola involved the armed forces of Cuba, South Africa, and the DRC—none of which are here considered major powers. The conflict caused over 1,000 battle deaths every year from 1975 to 1989. This minor power intervention is far more deadly than some examples of major power intervention. The Russian intervention in Georgia’s South Ossetia region in 2008 was associated with hundreds, not thousands, of battle deaths, while even fewer fatalities were recorded in the context of the UK’s intervention in Sierra Leone in 2000.

High-profile major power interventions that cause extremely high death tolls—from Vietnam to Afghanistan—capture most of the media’s attention. But, in fact, minor power interventions in civil wars are more often associated with high death tolls than major power interventions.

Some 61 percent of minor power interventions— by which we mean external military support that does not involve any of the major powers—in civil wars since 1946 were associated with battle-death tolls that crossed the highintensity, thousand-battle-death threshold for a year or more. Over the same period, just half of the intrastate conflicts in which major powers intervened crossed this threshold.

Conclusion

Some scholars have suggested that international military interventions are an effective means of ending civil wars. Ann Hironaka, for example, argues that “decisive external intervention” represents a “promising possibility” to end civil wars, citing the NATO missions in Bosnia- Herzegovina and Kosovo as examples. The doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), which was endorsed in principle by the UN General Assembly in 2005, also envisages the possibility of Security Council-mandated military interventions by the international community to protect civilians from war crimes, genocides, or other gross violations of human rights, which tend to occur during civil wars.

However, we have shown in this chapter that the support of foreign military forces for a warring party in a civil conflict is very generally associated with higher death tolls than is the case where there is no intervention. While in some cases military intervention can save lives, the reality is that we know very little about the necessary conditions for successful military interventions.

By contrast, there is much evidence to suggest that international efforts to resolve conflicts through diplomacy, negotiations, and peace operations have overall been successful in reducing the number of wars worldwide—as we have discussed in detail in the last Human Security Report. The following chapter analyzes trends in the duration and termination of civil wars and argues, among other things, that the large increase in the number of peacemaking and peacebuilding efforts since the end of the Cold War has helped make recent conflicts less persistent.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Human Security: Genesis, Debates, Trends

The Global Regime for Armed Conflict

Conflict Trends 2012