Human Security Report 2012, Chapter 8: Deadly Assaults on Civilians

31 Dec 2012

Editor's Note: This week the ISN takes the opportunity to highlight the comprehensive and scholarly insights provided by the 2012 Human Security Report. In particular, we focus on Part II of the report ("Trends in Human Insecurity"), which traces the incidence and severity of armed conflicts and other forms of violence at the regional and global levels. (The forms of violence include state-based conflicts, persistent armed conflicts, non-state armed conflicts and deadly assaults on civilians.)

The particular virtue of the 2012 report is that it debunks the conventional wisdom on a number of significant points. Among its conclusions are that military interventions in appear to increase death tolls in civil wars; that peace negotiations are in fact highly effective; that conflicts between non-state actors and one-sided violence against civilians have not increased over the past two decades; and that the number of conflicts worldwide appears to be stabilizing, despite significant year-to-year fluctuations. You can find the full contents of the 2012 Human Security Report external pageherecall_made, along with links to previous reports.

Our focus today is on the final chapter of Part II of the 2012 Human Security Report. After offering a careful definition of what constitutes one-sided violence against civilians, whether by governments or non-state actors, and during war or peace, the text then debunks the conventional wisdom that civilians are being increasingly targeted by this type of conflict. It admits, however, that because one-sided violence tends to contravene internal laws, the numbers might be inaccurately low.

Chapter 8: Deadly Assaults on Civilians

Since its inception, the Human Security Report has sought to present a comprehensive picture of trends in organized violence around the world. One-sided violence—the targeting of civilians with deadly force—is an important part of this picture. Yet, until recently, it has been largely understudied compared to other forms of organized violence.

Prior to 2005, global data on one-sided violence were limited. This permitted a number of mistaken beliefs to flourish unchallenged, including the widely accepted claim that civilians have been increasingly targeted in contemporary wars.

The Human Security Report Project (HSRP) commissioned the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) to create a dataset on onesided violence. The first findings were published in the 2005 Human Security Report.

Using an updated version of the dataset, this chapter reviews the global and regional trends in one-sided violence over the past 21 years, and some recent research findings. The data indicate that in 2009 the number of deadly campaigns against civilians was the lowest recorded since 1989—the earliest year for which UCDP has data. The conventional wisdom that civilians are increasingly being targeted in today’s wars is simply incorrect.

The data also reveal that between 1989 and 2009 most campaigns and deaths from one-sided violence were concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. Since the early 2000s, however, the incidence of one-sided violence in this region has declined. The Central and South Asia region has seen the second-highest number of campaigns against civilians—and fatalities—but here too there has been a decline in recent years. The remaining regions have suffered comparatively fewer campaigns of one-sided violence.

This chapter will also review the burgeoning research literature on organized violence against civilians that uses the new dataset to explore a range of issues related to one-sided violence.

What Is One-Sided Violence?

UCDP defines one-sided violence as the organized use of armed force directed at civilians by a government or a formally organized group that results in at least 25 reported deaths in a calendar year. Unlike civilians who die in the crossfire of armed conflict—and whose deaths are counted as battle-related deaths—victims of one-sided violence are the direct, rather than the inadvertent, victims of an attack.

“One-sided violence” is a relatively neutral term, and has thus far avoided the sort of controversy that swirls around the concepts of “terrorism” and “genocide”—both of which also focus on the killing of civilians. It is also in some ways a more inclusive category than either genocide or terrorism. First, it includes both large-scale massacres and small-scale campaigns that meet the fatality threshold of 25 reported deaths in a calendar year. The term “genocide,” on the other hand, generally applies to large-scale killings.

Second, one-sided violence can be perpetrated by either a government or a formally organized non-state group. There is disagreement about whether the term “terrorism” applies in cases where the government intentionally kills civilians. Most terrorism analysts argue that terrorism is the intentional use of violence against civilians for political ends by non-state groups, and argue that where governments intentionally kill civilians this may well be a war crime, but it is not terrorism.

Third, according to the standard definition, genocide has the goal of destroying, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, or religious group. The definition of one-sided violence does not involve identifying the target of violence—other than the fact that it is civilians. One-sided violence is a broader category than terrorism and genocide in some ways, yet it is narrower in one important respect: targets of one-sided violence must be unarmed civilians. In the literature there is no consensus with respect to whether victims of terrorism or genocide must be either civilian or unarmed.

"Collateral Damage" versus One-Sided Fatalities

As pointed out, civilians can become victims of organized violence outside of wars. Within the context of armed conflicts, however, there are two analytically distinct circumstances in which civilians can be killed. The first is when they are caught “in the crossfire” of combat— i.e., when they become the unintended victims of either gunfire, or exploding bombs or improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Such deaths are often euphemistically referred to as “collateral damage.” The second circumstance involves the targeting of civilians by government or nongovernment forces that often takes place during wars but sometimes also in peacetime. This is one-sided violence.

Although battle-related civilian deaths and one-sided violence both result in the death of noncombatants, they are conceptually different. The former is a in effect an inevitable consequence of fighting; the latter is the result of tactical choices by combatants to target civilians.

There are several reasons for treating deaths from the targeting of civilians separately from deaths of civilians caught in the crossfire. First, one-sided violence constitutes a crime under international law, whereas military engagements that inadvertently cause civilian casualties are not considered unlawful. The policy responses to situations in which civilian targeting is a war tactic differ from those in which civilians are accidentally caught in the crossfire of conflict.

Second, campaigns of one-sided violence may occur outside of war settings. Around 16 percent of campaigns of one-sided violence recorded in the dataset occurred in countries that did not experience civil conflict in the same year. One prominent example is the deadly assault on civilians by Chinese government forces in the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. These deaths would not be counted by data-gatherers for standard battle-death datasets because there was no combat. The victims did not, indeed could not, fight back.

Third, the level of one-sided violence varies substantially from conflict to conflict. Some conflicts see significant levels of one-sided violence; the most severe recent example, the Rwandan genocide in 1994, took place while the country was in the midst of a civil war. Yet, in other conflicts—for example, the intrastate conflict in Yemen in 1994—no instances of civilian targeting were recorded. The use of one-sided violence also differs among conflict actors. A 2011 study by Madelyn Hsiao-Rei Hicks et al. found that while 11 percent of non-state conflict actors targeted civilians as their “sole form of lethal behaviour in conflict,” 61 percent completely refrained from using one-sided violence.

In other words, the large-scale killing of civilians is not part of every armed conflict, nor does it play a role in every warring party’s strategy. But the variation in the use of one-sided violence can only be studied if the phenomenon is treated separately from collateral damage.

Even though there is a clear advantage in analyzing the two types of civilian fatalities separately, it is often difficult to clearly identify one-sided violence when it occurs. This is why there is a higher degree of uncertainty with respect to one-sided violence fatality numbers than is the case with data on battle deaths. The fact that killing civilians—unlike killing combatants—is universally proscribed means that governments and non-state armed groups are often reluctant to claim responsibility for acts of one-sided violence that they may perpetrate. Plus, the distinction between one-sided violence and collateral damage, while clear in theory, is often difficult to make in practice for those coding the data.

Research on One-Sided Violence

The recent availability of data on one-sided violence has already led to a small, but growing, number of analytic studies that are increasing our understanding of this phenomenon.

The study by Hicks et al. looks at the degree to which conflict parties resort to targeting civilians. Their finding—that most warring groups in conflict between 2002 and 2007 did not target civilians—shows that, notwithstanding claims to the contrary targeting civilians is not a widely employed tactic. Between 2002 and 2007, only 39 percent of conflict parties carried out some degree of one-sided violence.

Another stream of research looks at the drivers of one-sided violence. In 2009 Chyanda Querido, for example, examined cases of one-sided violence in the context of armed conflict and found that where countries in conflict possessed natural resources, such as easily lootable diamonds and onshore oil reserves, there was an increased probability that the government would carry out mass killings of civilians.

In 2007 Lisa Hultman and Kristine Eck of Uppsala University found that regime type is associated with the risk of one-sided violence. Autocratic regimes are associated with increased risks of one-sided violence perpetrated by government forces in wartime. However, somewhat surprisingly, there is a higher risk of one-sided violence in democracies than semi-democracies, although in the former case the perpetrators tend to be rebel groups rather than government forces.

In 2010 Reed Wood studied the relationship between a rebel group’s strength and its tendency to perpetrate one-sided violence. He found that weak rebel groups that lack the capacity to provide benefits to the civilian population are unlikely to receive voluntary support. In such situations, rebels use violence to coerce support from civilians because the latter are unwilling to provide it voluntarily.

Other research has analyzed some potential negative effects of efforts to support the resolution of armed conflict on one-sided violence. In 2010 Hultman looked at the effect of a peacekeeping presence in ongoing conflicts on the incidence of one-sided violence. She found that peace operations in an ongoing conflict setting can unintentionally increase the level of one-sided violence perpetrated by non-state groups. For example, warring parties facing an intervention might anticipate a settlement to the conflict and therefore target civilians as a “last-minute strategy” to gain territory.

In 2010 Margit Bussmann and Gerald Schneider examined whether various “protection of civilians” mechanisms are effective in restraining parties in civil war from targeting civilians. Their analysis revealed that the presence of a neutral actor, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), deters some government groups from targeting civilians, but fails to deter rebel troops.

Global and Regional Trends in One-Sided Violence

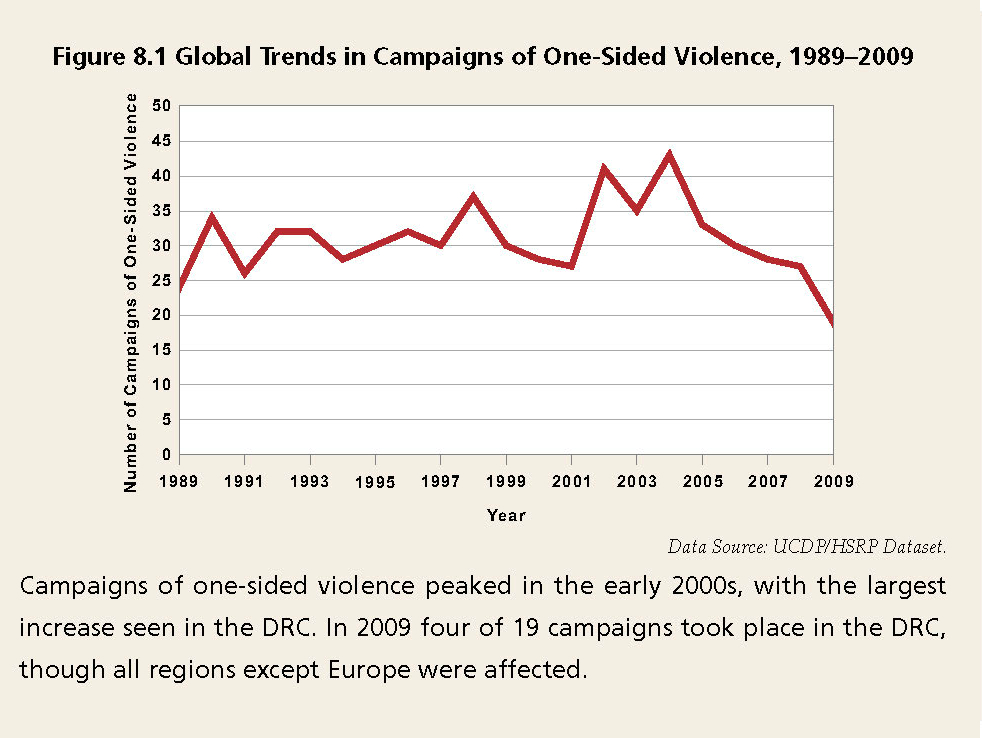

Figure 8.1 below shows the trend in campaigns of one-sided violence between 1989 and 2009. Although state-based conflict numbers declined in the post-Cold War period, one-sided violence campaigns increased unevenly until 2004 then started to decline. And, as the figure shows, the number of campaigns in 2009 was the lowest recorded between 1989 and 2009.

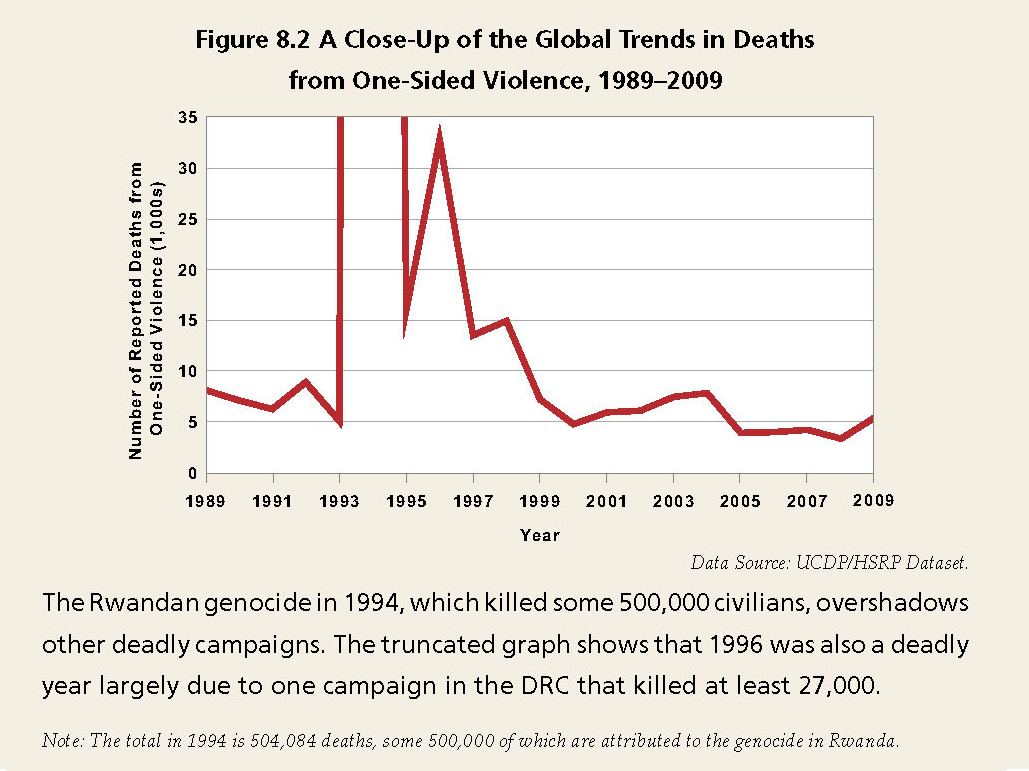

While there has been a clear decline in the number of campaigns of one-sided violence since 2003 and 2004, there has been no comparable decline in the number of fatalities caused by assaults on civilians. Figure 8.2 shows the global trends in deaths from one-sided violence between 1989 and 2009. Deaths from one-sided violence in 2009 increased by over 60 percent compared to the record low in 2008, but remain much lower than during the mid-1990s.

As noted earlier, deaths from one-sided violence are extremely difficult to estimate, which means that we should treat absolute numbers of estimated deaths in any particular year with due caution. There are obvious reasons why both governments and non-state groups might deny intentionally killing civilians, not least being that—unlike killing in combat— one-sided violence is a grave violation of international law. But there are also cases—Bosnia, for example—where one-sided violence estimates have been grossly overestimated.

UCDP’s estimates of one-sided violence are revised as new information becomes available. For example, the version of the data presented in this Report contains a major revision to the death toll from deadly assaults on civilians in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Previous estimates had indicated that the rebel group Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) killed around 6,000 civilians in 1996. New evidence, however, has increased that the figure to at least 27,000.

In the deadliest years in the dataset—1994 and 1996—the overwhelming majority of the fatalities recorded in each year were generated by just one campaign in that year. In 1994 the genocide in Rwanda caused 99 percent of the deaths from one-sided violence in that year. The AFDL’s campaign in the DRC caused 84 percent of the global one-sided death toll in 1996.

The tendency for a few campaigns to be responsible for the majority of the yearly death tolls also helps explain the uptick in fatalities from 2008 to 2009. Although there were 19 campaigns of one-sided violence in 2009, just two campaigns—again in the DRC—were responsible for half the global death toll that year. Most of the campaigns in 2009 were not very deadly by comparison; indeed, if we exclude these two campaigns, the average death toll for each campaign in 2009 was just over 150.

Despite the increase between 2008 and 2009, deaths from one-sided violence have declined substantially since the mid-1990s. The trend remains the same even if we exclude the huge and unprecedented death toll from Rwanda. Absent Rwanda, the average death toll from one-sided violence per year declined by half in the new millennium compared to the period 1989 to 1999.

When it comes to determining which type of actor—government or non-state group—has been the deadliest perpetrator of one-sided violence, there is no clear-cut answer. Between 1989 and 2009, governments were responsible for 83 percent of global deaths from one-sided violence. However, this result is predominantly driven by one-sided violence campaigns in the first half of the period considered. One prominent campaign, as we discuss below, is the Rwandan genocide in 1994, in which (according to UCDP’s “best estimate”) some 500,000 civilians were killed at the hands of the government. Indeed, the data show that the share of onesided violence deaths perpetrated by non-state actors has clearly grown over time. This trend, highlighted in our last Report, continues to be supported by the updated data: between 1989 and 1999, non-state groups were responsible for 12 percent of the deaths. In the new millennium, however, they were responsible for 70 percent of the deaths—a remarkable shift.

Regional Trends

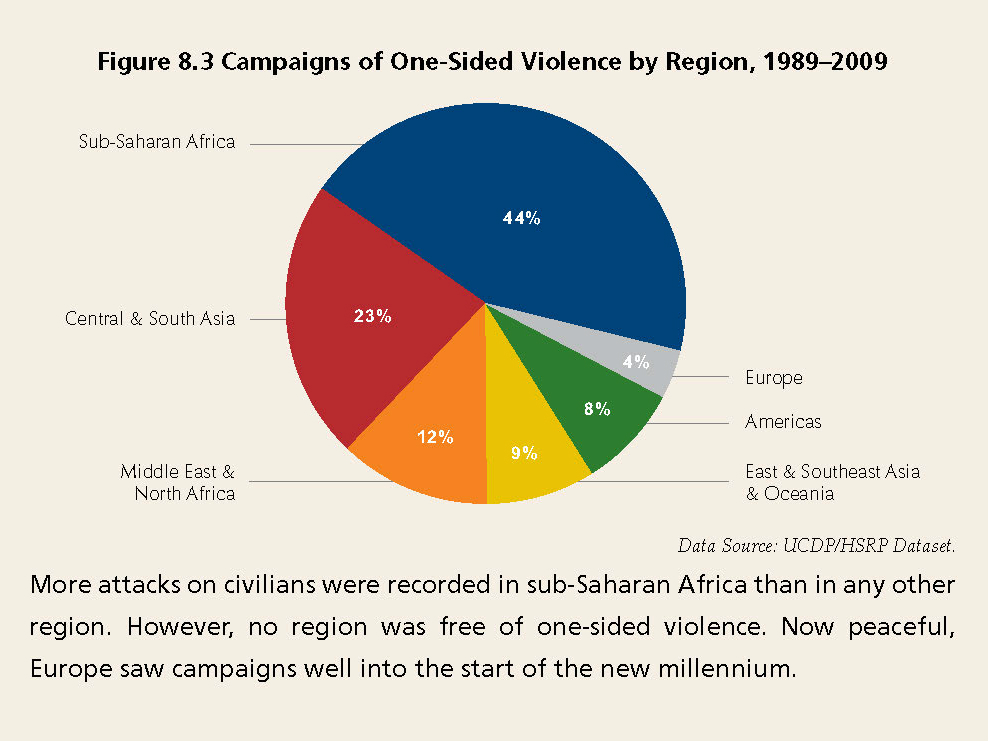

The percentage of campaigns and fatalities due to one-sided violence varies substantially between regions. Figure 8.3 shows the proportion of campaigns of one-sided violence for each region. Just under half of all recorded campaigns took place in sub-Saharan Africa. Central and South Asia was second with just under a quarter of the total campaigns, followed by the Middle East and North Africa with 12 percent.

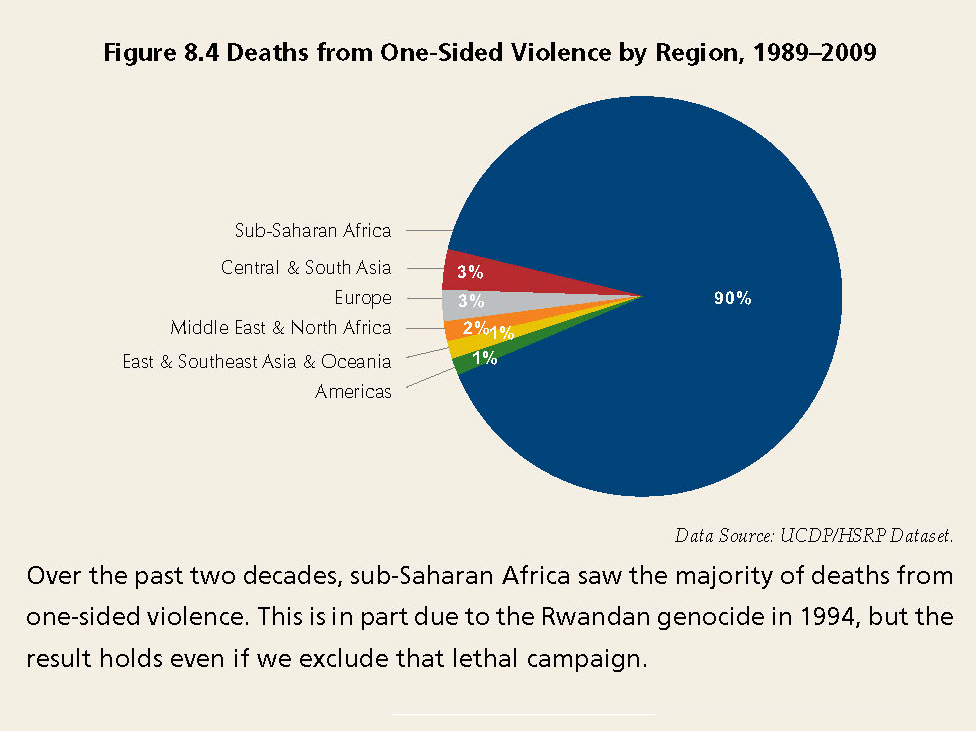

The divergence between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the regions is even more marked when we look at fatalities. Figure 8.4 shows the proportion of deaths due to one-sided violence that occurred in each region.137 Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 90 percent of the total number of fatalities from one-sided violence between 1989 and 2009. By contrast, the region accounted for just under half of all battle deaths from state-based conflict in the same period.

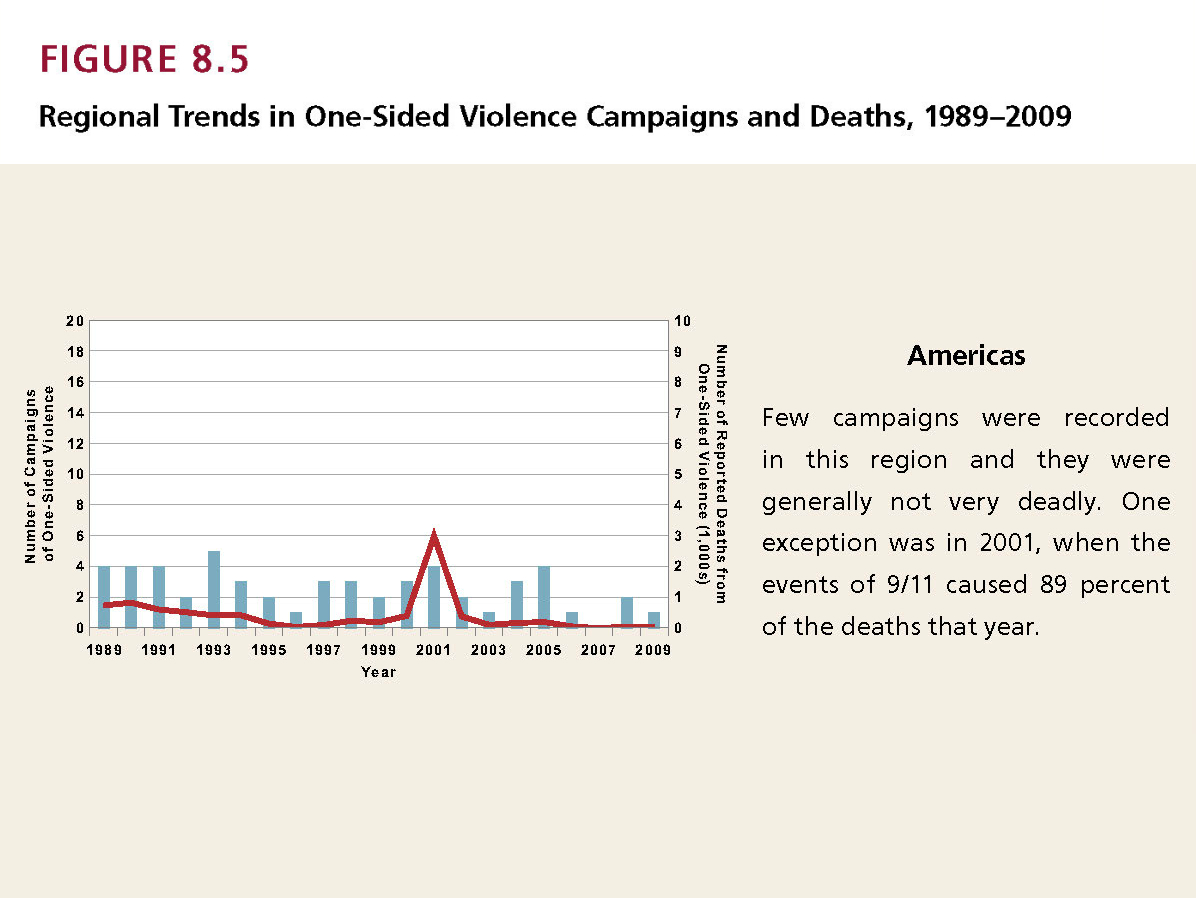

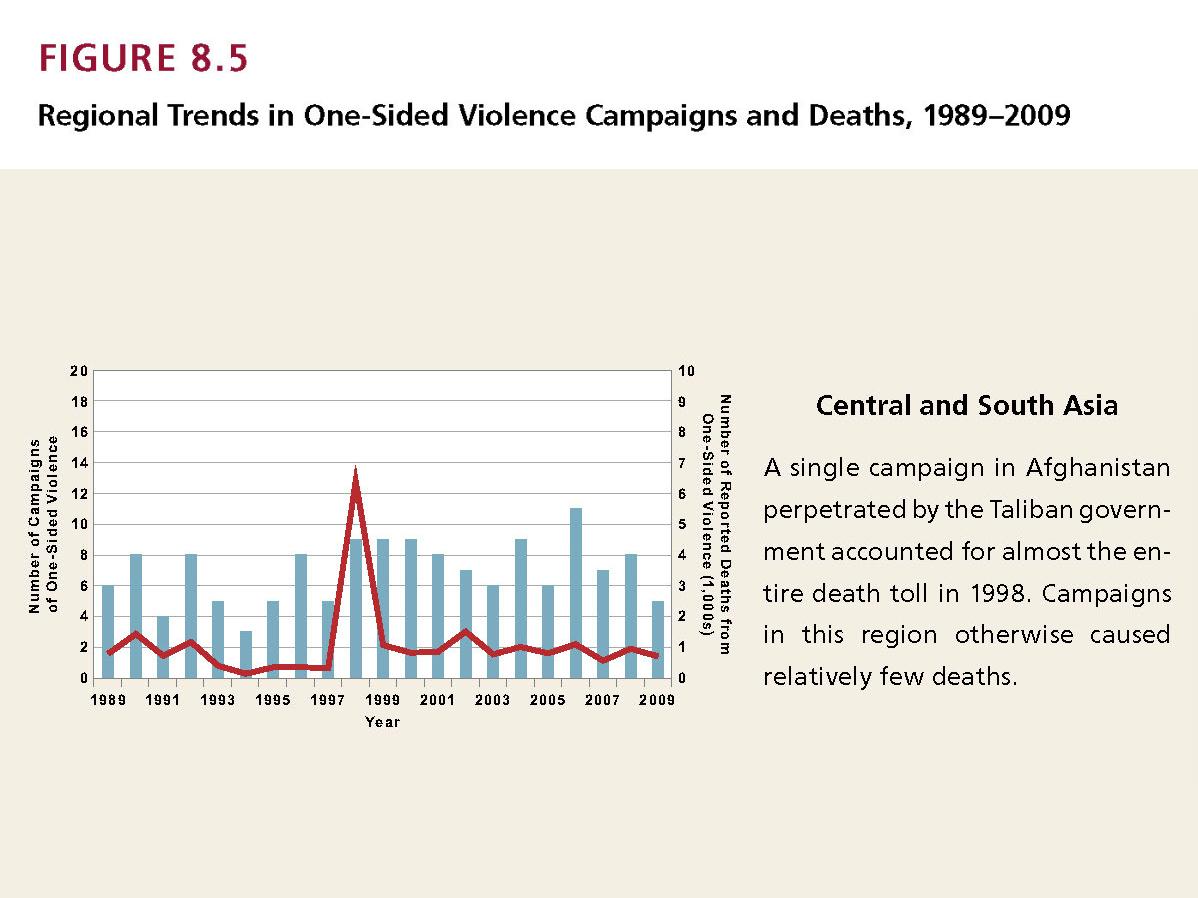

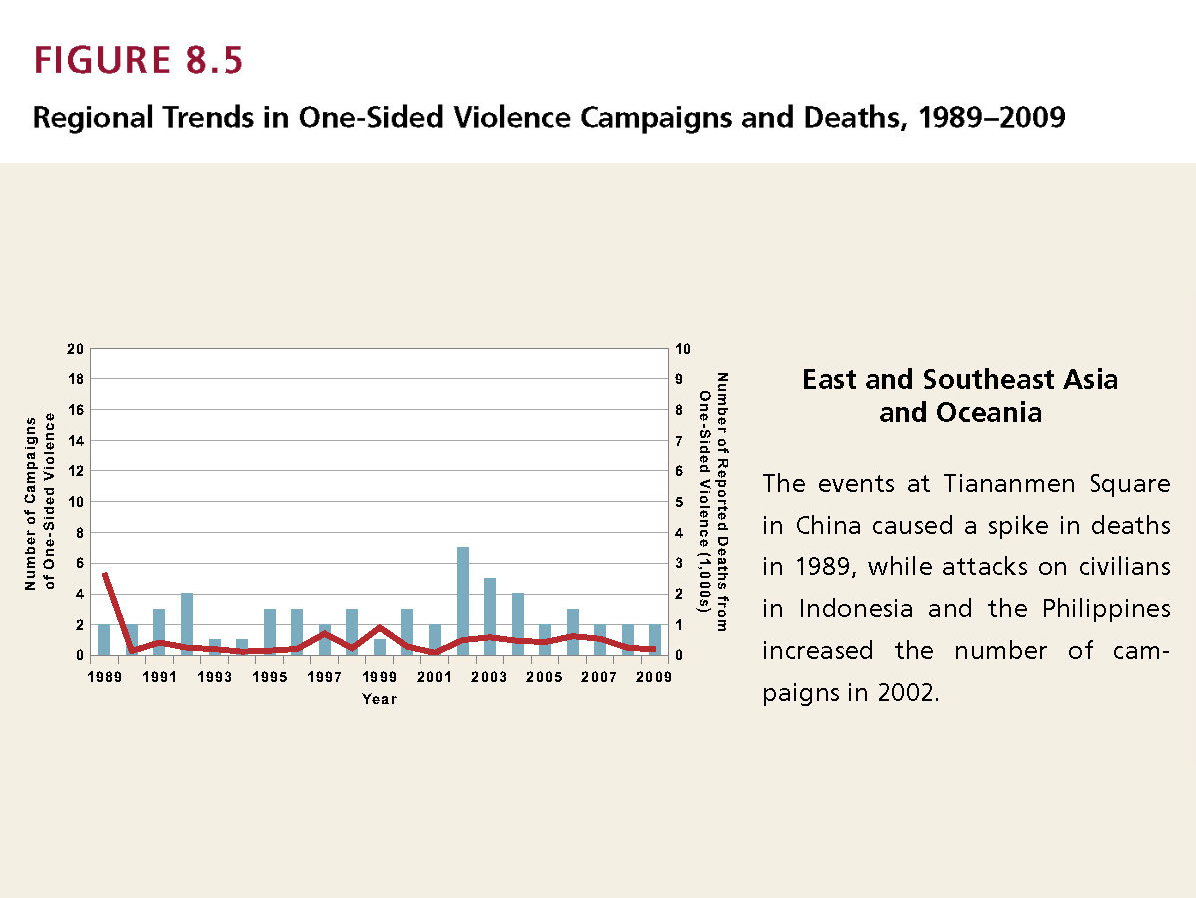

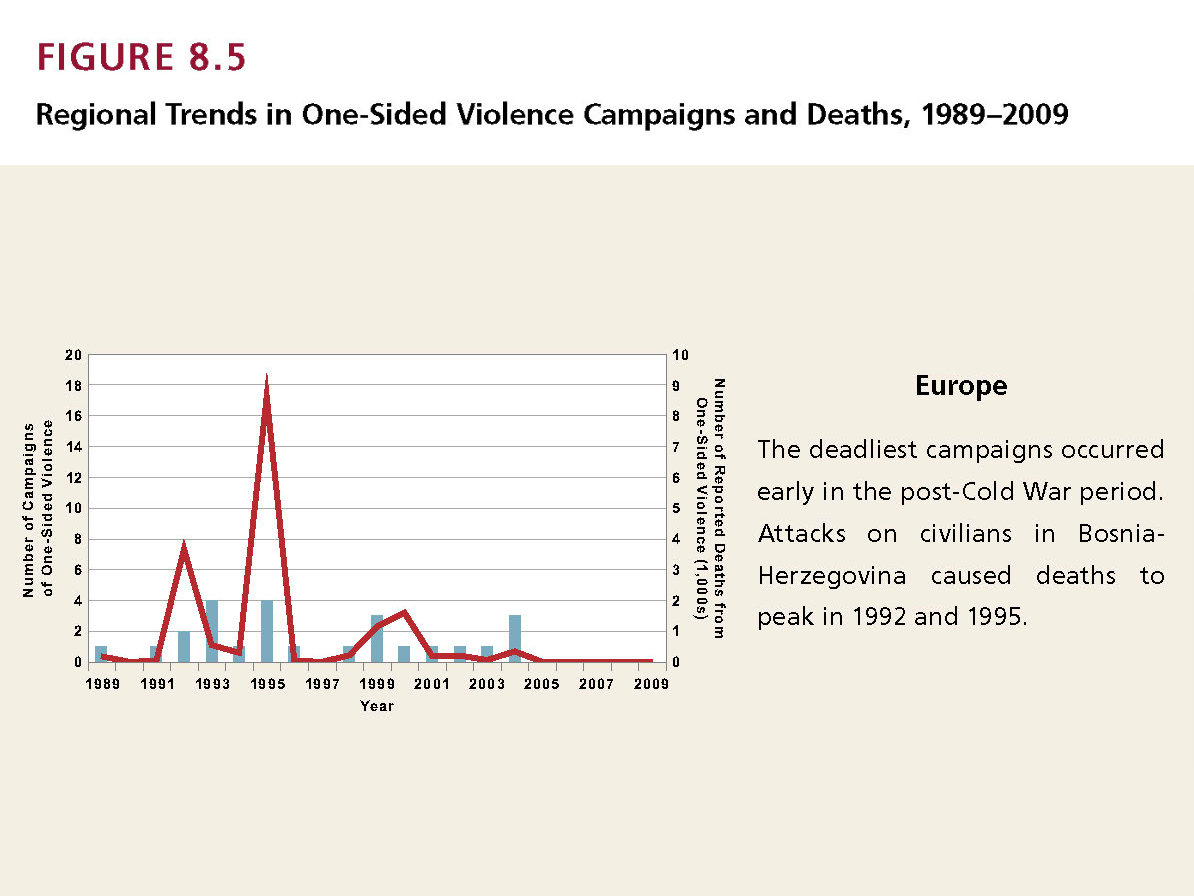

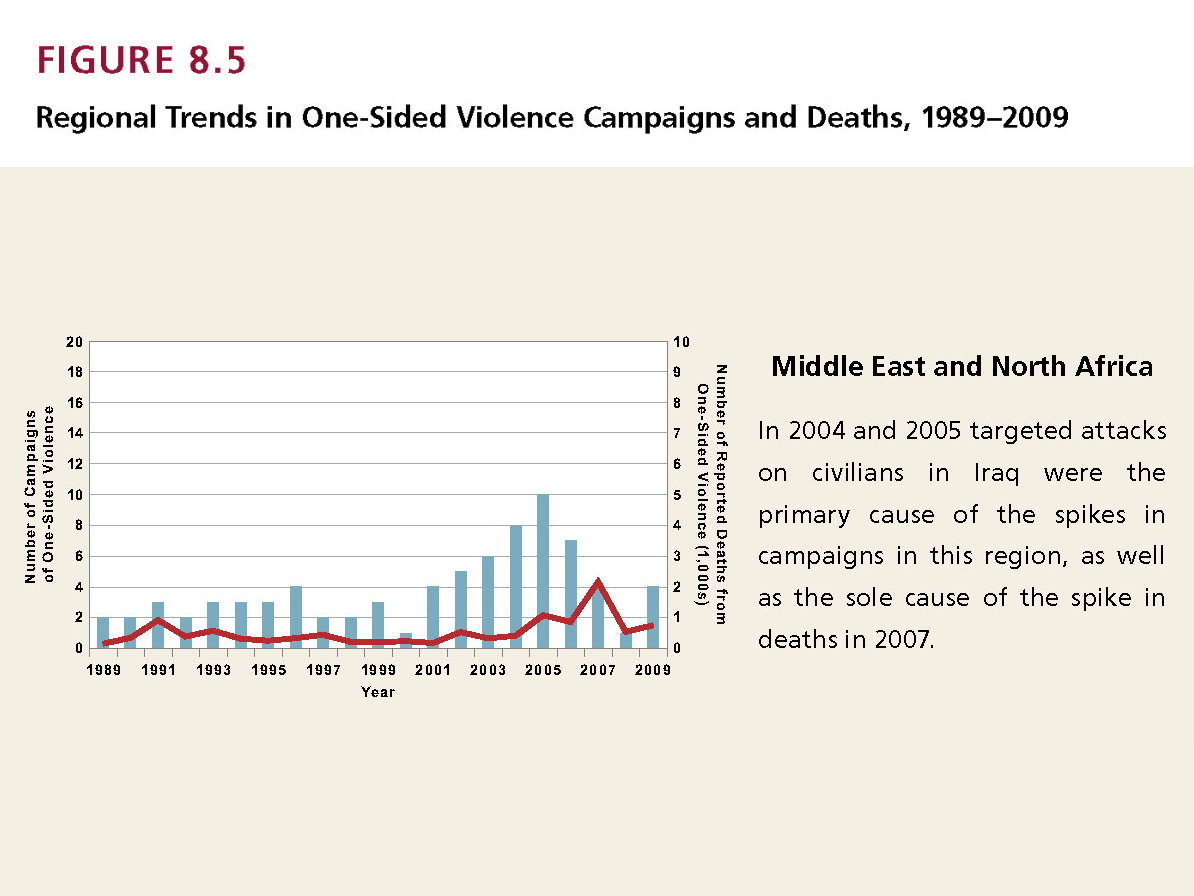

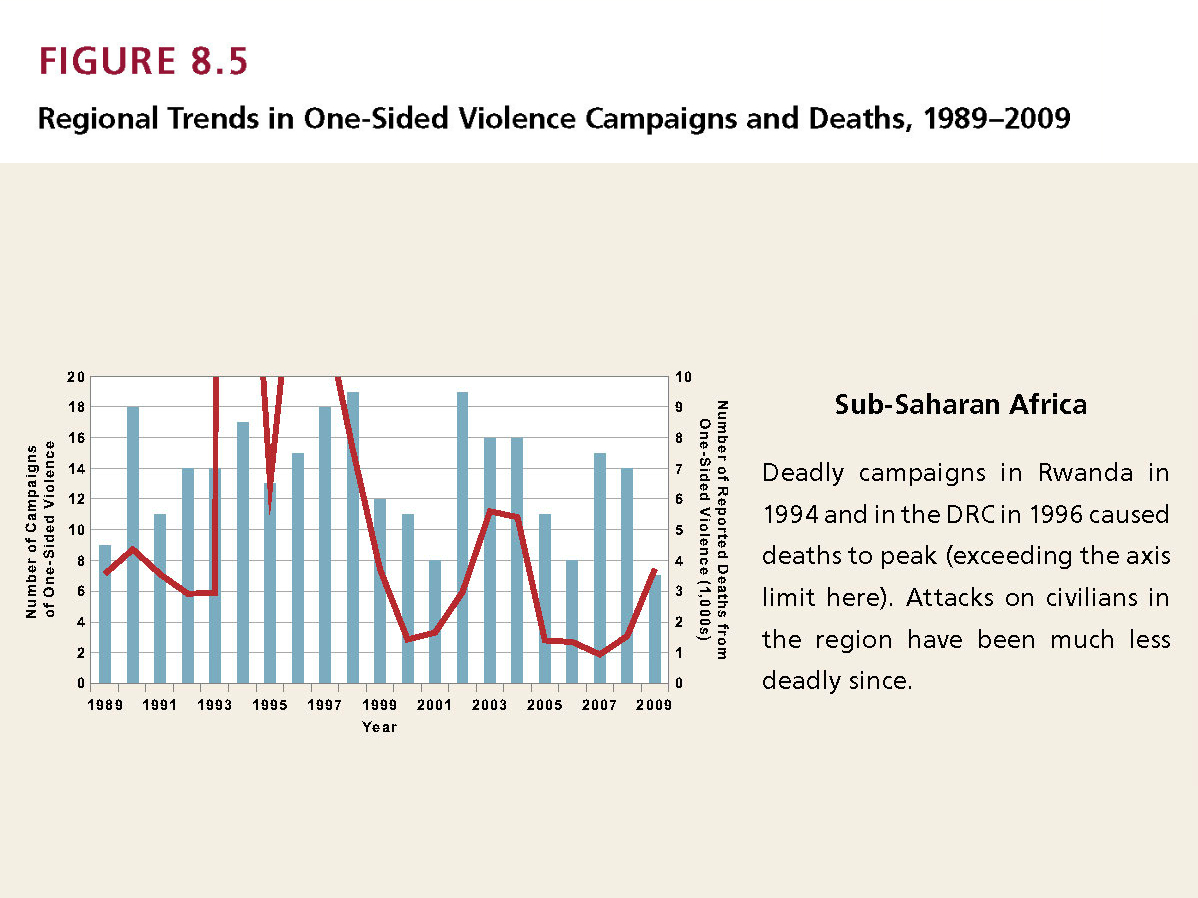

The regional differences can also be seen in the trends over time. Figure 8.5 shows the trends in one-sided violence campaigns and deaths between 1989 and 2009 for each region.

In almost every year the death toll was higher in sub-Saharan Africa than in any other region. Because sub-Saharan Africa had such a large share of total civilian deaths, its trend tends to drive the worldwide trend.

For example, the global peaks in the death tolls in 1994 and 1996 were due to one-sided violence campaigns in Rwanda and the DRC, respectively. Campaigns in sub-Saharan Africa were also responsible for the recent global increase in deaths due to one-sided violence between 2008 and 2009. The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), both active in the DRC, perpetrated the deadliest campaigns of one-sided violence in 2009.

Governments in sub-Saharan Africa were responsible for the overwhelming majority—88 percent—of deaths in the region. However, as was the case at the global level, this was primarily a result of the staggering death toll in a single case—the Rwandan genocide. If Rwanda is excluded from the analysis government actors were responsible for just over a third of civilian fatalities.

Death tolls in sub-Saharan Africa as a proportion of the global tolls have been much lower in recent years compared to those in the 1990s. The region suffered 93 percent of the global total fatalities between 1989 and 1999, but less than half the total between 2000 and 2009.

The region has also witnessed a decline in the number of campaigns of one-sided violence. Indeed, much of the global decline in campaign numbers since the mid-2000s can be attributed to the decline in sub-Saharan Africa.

Although sub-Saharan Africa stands out for having the highest number of campaigns of, and fatalities from, one-sided violence, no region was free of deadly assaults against civilians between 1989 and 2009.

Central and South Asia had the second-highest number of deadly assaults against civilians. The number of campaigns of one-sided violence in this region fluctuated from year to year between 1989 and 2009. In 2006 the region saw a slight increase due in part to new campaigns in India.

In 1998 deaths due to one-sided violence in the region spiked sharply. A campaign by the Taliban, which controlled the Afghan government at the time, resulted in nearly 6,000 civilian deaths. Since then, estimated annual death tolls in the region have varied between 500 and 1,500.

The Middle East and North Africa saw just 12 percent of the global campaigns and less than 2 percent of global fatalities. However, it is one of three regions—including Central and Southeast Asia, and East and Southeast Asia and Oceania—to have had more campaigns of one-sided violence in the new millennium than during the 1990s. In the Middle East and North Africa, the total number of campaigns in the 2000s was 85 percent higher than in the previous decade—a much larger increase than the ones seen in the other two regions.

Since the mid-2000s, however, the Middle East and North Africa has seen a downward trend in the number of campaigns. The number has decreased 60 percent from the peak year in 2005, while deaths have declined 65 percent since the peak year in 2007. As a consequence of the so-called Arab Spring, there may well be a considerable increase in both campaign and fatality numbers in 2011. At the time of writing, these data are still being collated.

The most active perpetrator in the Middle East and North Africa was the government of Iraq, which committed one-sided violence against civilians in 11 of the 21 years covered by the data. Its activity spanned two countries, Iraq and Kuwait—though in Kuwait there were only two campaigns, in the context of the Gulf War in the early 1990s. In Iraq, however, the government perpetrated one-sided violence every year between 1991 and 1996, then again in 1999, and then every year from 2005 to 2007.

The East and Southeast Asia and Oceania region saw comparatively few campaigns of one-sided violence. The deadliest perpetrator in the region was the government of China. During the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, government forces killed some 2,600 people, accounting for 27 percent of all one-sided violence in the region between 1989 and 2009. It is, however, difficult to obtain accurate information on one-sided violence in China and other countries with tightly controlled media. The death toll, in fact, may well be much higher than that which UCDP records.

In 2002 East and Southeast Asia and Oceania suffered the highest number of campaigns of one-sided violence in any year covered by the data. In Myanmar and the Philippines, deadly campaigns of violence against civilians were associated with state-based armed conflicts that were being waged at the same time. In Indonesia the majority of the deaths that year can be attributed to the bombings in Bali, which killed over 200 people. Although the number of campaigns in the region began to decline in 2003, the number of fatalities did not significantly decline again until 2008 and 2009.

Like East and Southeast Asia and Oceania, the Americas region has accounted for only a small proportion of the total campaigns of one-sided violence, and most kill fewer than 100 civilians a year.

The deadliest campaign in the region took place in 2001 in the United States. The deaths associated with the events on 11 September accounted for 45 percent of the global total deaths due to one-sided violence that year.

The perpetrators of the highest number of campaigns of one-sided violence in the Americas were Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) non-state armed groups in Colombia. FARC perpetrated one-sided violence every year in the dataset from 1994, except 2007, while AUC killed civilians each year from 1997 through 2005, with the exception of 2003. These campaigns are connected to the ongoing drug-fuelled civil war in the country. AUC has also fought another rival group, National Liberation Army (ELN), and FARC has long been fighting against the government of Colombia.

Europe saw the fewest campaigns of one-sided violence. But the campaigns that occurred in the region tended to be deadly, though the high deaths tolls may have reflected more complete reporting than may have occurred in some other regions. In fact, after sub-Saharan Africa, Europe saw the highest number of campaigns causing 1,000 or more deaths a year. This was primarily a result of the one-sided violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the Caucasus region of Russia.

Campaigns in Bosnia and Herzegovina caused an estimated 40 percent of the global death toll from one-sided violence in 1992, and 53 percent in 1995. The Russian government’s deadly assaults against civilians in Chechnya caused the spike in deaths seen at the start of the millennium.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Enhancing Protection Capacity

Protecting Civilians? The Interaction Between International Military and Humanitarian Actors

Syria: In Front of a Horrified and Passive World