Human Security Report 2012, Chapter 6: Persistent Armed Conflict - An Increasing Threat?

27 Dec 2012

Editor’s Note: This week the ISN takes the opportunity to highlight the comprehensive and scholarly insights provided by the 2012 Human Security Report. In particular, we focus on Part II of the report ("Trends in Human Insecurity"), which traces the incidence and severity of armed conflicts and other forms of violence at the regional and global levels. (The forms of violence include state-based conflicts, persistent armed conflicts, non-state armed conflicts and deadly assaults on civilians.)

The particular virtue of the 2012 report is that it debunks the conventional wisdom on a number of significant points. Among its conclusions are that military interventions in appear to increase death tolls in civil wars; that peace negotiations are in fact highly effective; that conflicts between non-state actors and one-sided violence against civilians have not increased over the past two decades; and that the number of conflicts worldwide appears to be stabilizing, despite significant year-to-year fluctuations. You can find the full contents of the 2012 Human Security Report external pageherecall_made, along with links to previous reports.

Our focus today is on Chapter 6 of the HSR, which focuses on "persistent armed conflicts" – i.e., those confrontations that result in more than 25 battle deaths per year over a prolonged period of time. In investigating this type of struggle, the chapter demonstrates that in contrast to what has been argued in the past, there is little support for an overall trend towards longer conflicts. Today's high rate of conflict relapse is not so much due to the failure of peace building, but rather due to the fact that most of today's civil wars are very small in scale. Peace agreements are much more successful than is usually assumed: they save lives even when they fail.

Chapter 6: Persistent Armed Conflict – An Increasing Threat?

It is now widely accepted that the number of armed conflicts has declined substantially over the last two decades. But there are warnings of serious and even growing causes for concern: that wars are lasting longer than before and that, even when wars stop, violent conflict is increasingly likely to recur. In short, it is argued conflicts are becoming more difficult to resolve.

This bleak assessment has certainly received support from some influential conflict researchers. For example, James Fearon asserted in 2004 that “the average duration of civil wars in progress has been steadily increasing throughout the postwar period, reaching almost 16 years in 1999.” Paul Collier and colleagues, as well as Ann Hironaka, have made similar claims. If it is indeed the case that conflicts are lasting longer on average, then this is bad news for efforts to end them.

It is true that numerous conflicts have remained unresolved for decades. The conflict between Israel and the Palestinians was recorded as active for 58 of the 64 years from 1946 to 2009, the period covered by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) and Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) datasets on which we primarily rely for our analyses. Other conflicts that have lasted decades include those in Burma, the Philippines, and Colombia. And even civil wars in Algeria, India, and elsewhere that started more recently—in the 1980s or 1990s—have already continued for more than a decade.

An additional cause for concern is that in an increasing share of instances where conflicts have stopped, the violence starts up again within a short time. The World Bank World Development Report (WDR) noted in 2011 that repeated cycles of violence and recurring civil wars have become “a dominant form of armed conflict in the world today,” pointing out that “90 percent of conflicts initiated in the 21st century were in countries that had already had a civil war.”

If these analyses are correct—if conflicts are becoming much more protracted, more likely to restart once stopped and therefore more difficult to resolve—this raises an important question. Were the vast number of international initiatives that were launched after the end of the Cold War to stop conflicts and prevent them from starting again as effective as the Human Security Report Project (HSRP) and others have argued?

However, while recognizing that conflict persistence is an important policy issue, we argue in this chapter that a closer examination of the data reveals a considerably more encouraging picture than other authors suggest. Most of today’s conflict episodes are relatively short; long-lasting conflicts are increasingly the exception rather than the rule. Persistent conflicts are often very small in scale, and the higher rates of recurrence of conflict result in large part because conflicts have become more difficult to win—but not necessarily more difficult to resolve. An increasing proportion of conflicts is terminated by negotiated settlements, the majority of which prevent the recurrence of violence. We further find that even when peace deals collapse, the death toll due to subsequent fighting is dramatically reduced.

Defining and Measuring Conflict Persistence

What do we mean by conflict persistence? Generally, concern about armed conflicts arises not because governments and their non-state rivals have serious disputes, but primarily because they attempt to resolve such disputes through armed violence, which is highly destructive and disruptive. Simply speaking, a persistent conflict is therefore one that involves many years of fighting.

Conflicts that have resulted in armed combat for long periods without interruption are persistent according to this definition, but so too are those that repeatedly stop and then start again, accumulating many years of fighting in the process. We therefore approach persistence from different angles, looking at the duration of armed conflicts, as well as rates of conflict recurrence. Findings on how long conflicts last and how frequently they recur, however, depend to some extent on how onsets and terminations of conflicts are defined.

Most studies on conflict duration and recurrence focus on civil wars—or intrastate conflicts as they are defined in the datasets used here—because they are not only the most common type of conflict but also the most persistent. Following this practice, the chapter will also be limited to conflicts that occur within rather than between states. An armed intrastate conflict in UCDP/ PRIO terms consists of state forces fighting one or more rebel groups over either government power or the control of a certain territory, leading to at least 25 battle deaths per year.

But how do we distinguish between a new conflict and a recurrence? And what exactly does “uninterrupted” fighting mean? Does a cessation of hostilities lasting for a few years mark the end of a conflict or simply the end of an episode within the same armed struggle?

Some researchers consider a conflict terminated when it causes fewer than 1,000 battle deaths within a calendar year; others apply lower casualty thresholds and require a two-year break in the fighting to qualify as a termination. One dataset may record certain events as a single long-lasting conflict, another might count the same events as a series of violent episodes within one conflict, while a third may count these events as two separate conflicts. Trends and analytical findings based on these definitions differ as a result.

The UCDP/PRIO armed conflict dataset and the related UCDP conflict terminations dataset that we primarily use here avoid this problem by allowing the study of both distinct episodes of fighting as well as conflicts consisting of several such episodes of fighting between the same actors or over the same issues.

The datasets code a conflict as active for each year in which it results in at least 25 battle deaths. When the conflict’s death toll falls below this threshold for one calendar year—and thus the fighting is interrupted—this marks the end of a conflict episode.

Even when the fighting dies down below this death-toll threshold, the conflict is not necessarily over. The dispute between Israel and the Lebanese group Hezbollah, for example, was last active (using the UCDP/PRIO definition) in 2006, but few would argue that the conflict—the core antagonism between the rival parties—is really over. The cessation of hostilities in 2006 is counted in the UCDP/PRIO dataset as the end of an episode. If violence breaks out again between these two parties, the dataset will list a new episode within the same conflict. A new conflict, on the other hand, is recorded when fighting erupts between any two parties over an issue that was not previously contested.

The UCDP terminations dataset records, as precisely as possible, start and end dates for all conflict episodes. The dataset includes information about the outcome of conflict episodes: this can be a peace agreement, a ceasefire, a victory, or—if a conflict falls below the battledeath threshold without a decisive event—“low or no activity” (which in the following we refer to as “other terminations”).

All of these termination types can mark the end of a conflict—or merely an interruption of the fighting. Some of the communist insurgencies in East Asia, for example, dropped below the battle-death threshold without an outright victory or a peace settlement but never started up again. In Afghanistan, on the other hand, the conflict halted for a short while due to the victory of the US- and NATO-backed “Northern Alliance” over the Taliban government in 2001. The Taliban have since regrouped and the violence has resumed.

The UCDP/PRIO data allow us to study the duration of armed conflicts, whether as continuous episodes of fighting or in terms of the total number of years that an intermittent dispute results in battle deaths. We can also track patterns in how conflict episodes end and whether or how often they recur. This enables our analysis of persistent conflict to look at both conflicts that last for many years without interruption and conflicts that result in a substantial number of years of warfare spread out over periods of intermittent violent struggle.

This definition includes long-running, uninterrupted conflicts such as the civil war in Colombia, which has been active in each year since 1964, as well as intermittent struggles such as the conflict over the Cabinda territory in Angola, which has broken out in seven episodes of deadly violence since 1989, adding up to nine conflict years in total. In both cases, we have a record of many years of armed clashes, but different patterns of violence.

We use the term persistent conflict to include all forms of intrastate conflict that result in more than 25 battle deaths per year over a prolonged time period. The definition includes some conflicts that have seen resolution attempts, but persistent conflicts are not necessarily “intractable”; instead, many may persist simply because no real effort has been put into ending them.

Are Conflicts Really Lasting Longer than Before?

In 2003 Paul Collier found evidence that “decade by decade, civil wars have been getting longer.” This widely accepted finding appears to be supported by other studies: James Fearon, for example, points out that the average duration of civil wars has almost trebled since the 1960s. The UCDP/PRIO dataset, which use a slightly different definition of armed conflict, reveal a less consistent trend, but the duration of civil wars still shows an increase over the same period.

Due to the different definitions and datasets, Fearon’s numbers are not directly comparable with ours. But we argue that this way of measuring trends in duration represents in any case only one part of the picture. A significant problem arises because figures such as those relied upon by Fearon are affected by a strong upward bias over time. The average duration of ongoing conflicts is skewed upward by the longerrunning conflicts or conflict episodes. Short conflicts or conflict episodes will be factored into the average as long as they are active. But once they stop, they cease to be part of the sample and their duration will not affect the average the following year, while the longerrunning conflicts keep pushing the average up.

Thus, as long as some persistent conflicts remain, the average duration of conflicts in progress will go up in most years. Understanding what determines the persistence of these conflicts is important, but as Roy Licklider observed, long-running conflicts are clearly not the norm but rather outliers. And even though Fearon’s measure correctly shows that the world has a significant number of persistent conflicts today, it tells us little about how this compares to other time periods.

Focusing on the most persistent cases does not allow us to analyze whether more or fewer conflicts are now persistent than before. It also does not tell us enough about whether changes in the ways that conflicts are fought and brought to an end have affected their persistence. These are, however, critical questions for the design and evaluation of policy responses.

A Different Perspective Reveals a Decline in Conflict Duration

To understand whether, at any given time, more or fewer conflicts are becoming persistent, it is useful to look at the average duration of conflicts and conflict episodes that started in the same year or the same time period. Unlike other metrics, this ensures that persistent conflicts are not given more weight than other conflicts.

When viewed from this angle, the data show that there is ample reason to doubt that most conflicts are lasting longer than they used to. In fact, the average duration of conflict episodes, sorted by start date, shows a clear downward trend. Episodes starting in the 1970s lasted almost seven years on average, but the average duration dropped to around four years in the 1980s. By the end of that decade, the average duration was around three years and has remained roughly at the same level since. The drop in duration is slightly larger when we count entire conflicts rather than just episodes.

We must be careful, however: measuring trends in duration based on start dates also contains a bias. In this case, it is downward: a conflict episode that started in 1950, for example, could theoretically have lasted 60 years by the year 2009—the most current entry in the dataset—while the maximum duration of an episode starting in 2006 would be four years. The most recent conflicts may only appear to be short at this stage because we cannot look into the future to determine their end dates.

But the sharp decline in the duration of conflict episodes—by more than half—around the mid-1980s is too steep to be wholly the result of this bias. Not only did some long-standing conflicts end during the late 1980s but the proportion of civil conflicts lasting longer than average has declined significantly since the 1980s.

Long Periods of Fighting Have Become Less Common

These two different ways of calculating the average duration of civil wars both have their limitations, as shown above. Another way to track how civil war duration has changed over time is to determine how many of the conflicts that started each year eventually exceed a specified length. When applied to uninterrupted episodes of fighting, this measure shows no bias over time, since each episode has the same chance of reaching the threshold. If the proportion of conflict episodes that are longer than the specified length has risen over time, then this clearly indicates an increase in conflict persistence.

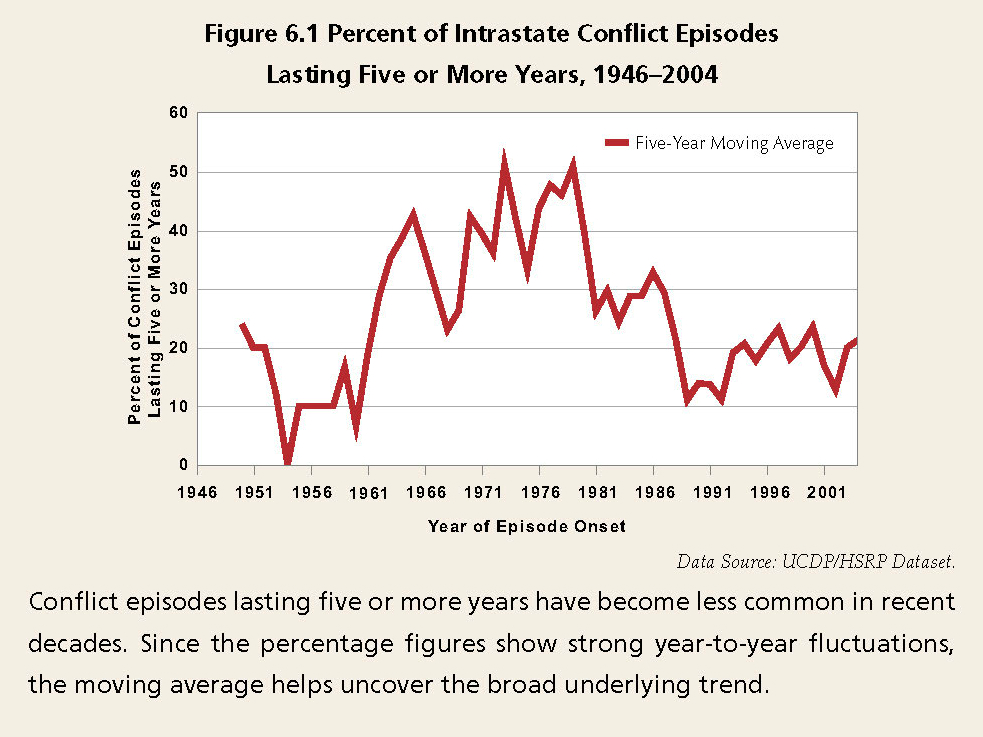

Civil war episodes since the end of World War II have lasted on average approximately four years and three months. We therefore applied a threshold of five years to capture conflict episodes that have been longer than average. The results are shown in Figure 6.1.

The trend line in Figure 6.1 shows that onsets of conflict episodes that lasted five years or more have clearly become less common in recent years. Their share was highest during the 1970s, when almost half of all conflict episodes resulted in five or more years of fighting. This was followed by a decline during the 1980s and, since the 1990s, the share of longer than- average episodes of conflict has remained lower at approximately 20 percent. In other words, roughly 80 percent of the more recent conflict outbreaks were followed by less than five years of continuous fighting. The fact that this figure is significantly higher than during the preceding decades counters claims that there has been a general increase in conflict duration. Recent conflict episodes appear to be less persistent, not more, than those that started earlier.

The duration of uninterrupted conflict episodes gives just one indication of trends in conflict persistence. As explained above, many conflicts stop and start up again after a short break in the fighting. The downward trend shown in Figure 6.1 is confirmed, however, if we look at the cumulative duration of conflicts—i.e., if we consider all conflicts that resulted in a total of five or more active years that may have been interrupted by a period of inactivity. Application of other thresholds as a way of testing the strength of this conclusion does not significantly alter the trend.

Results drawn from data that include intermittent conflicts may change in the future if more conflicts break out in violence again. Still, the fact that the downward trend in onsets of longer-than-average conflicts and conflict episodes is consistent even when the data are examined in various ways undermines claims that conflicts are generally lasting longer and longer, and counters warnings that persistent conflict is an increasing threat.

Summing Up: Conflict Duration Is Not Generally on the Rise

Our analysis demonstrates that different ways of looking at changes in conflict duration over time reveal different trends in conflict persistence. All of these findings convey important messages.

There is no question that a significant number of persistent conflicts exists today. Twelve—or 18 percent—of the 65 civil conflicts recorded between 2000 and 2009 were active in every single year of that decade. This includes the chronic violence in parts of Ethiopia (Oromiya), in Algeria, India (Assam and Kashmir), and Colombia. These persistent conflicts pose major challenges and, as discussed above, they drive up the average duration of conflicts in progress.

These cases are, however, not necessarily representative of overall patterns. Civil wars that have persisted for decades are often difficult to resolve and, obviously, get longer every year. But this does not suggest that conflict persistence in general is a bigger problem than it was during previous periods.

Our analysis shows that the conflict episodes that have started recently tend to be short. The overwhelming majority of episodes of fighting that started since the end of the Cold War have been brief. As we have shown, the proportion of conflict episodes that are shorter than five years increased significantly during the 1980s.

Many of the conflicts active today have multiple episodes, stopping and starting again. We will take a closer look at recurrences in the remainder of the chapter. However, the trend towards shorter duration in recent conflicts discussed above still holds true when we add up the total number of active years spread over a number of episodes. The trend revealed in Figure 6.1 does not, therefore, result simply from the fact that today’s conflicts tend to split into many short episodes. More than a third of the conflicts that started since the end of the Cold War have been both short and nonrecurring—in other words, they are far from persistent.

Yet, the tendency of many contemporary conflicts to stop and start again after a short lull in fighting is a reality as well. Approximately half the conflicts that started during the 1990s had more than a single episode. Understanding why conflicts start up again after a halt is therefore crucial for explaining trends in conflict persistence and for the design of policies aimed at peacemaking. The following section takes a closer look at how conflicts end and recur.

Increases in Conflict Recurrence

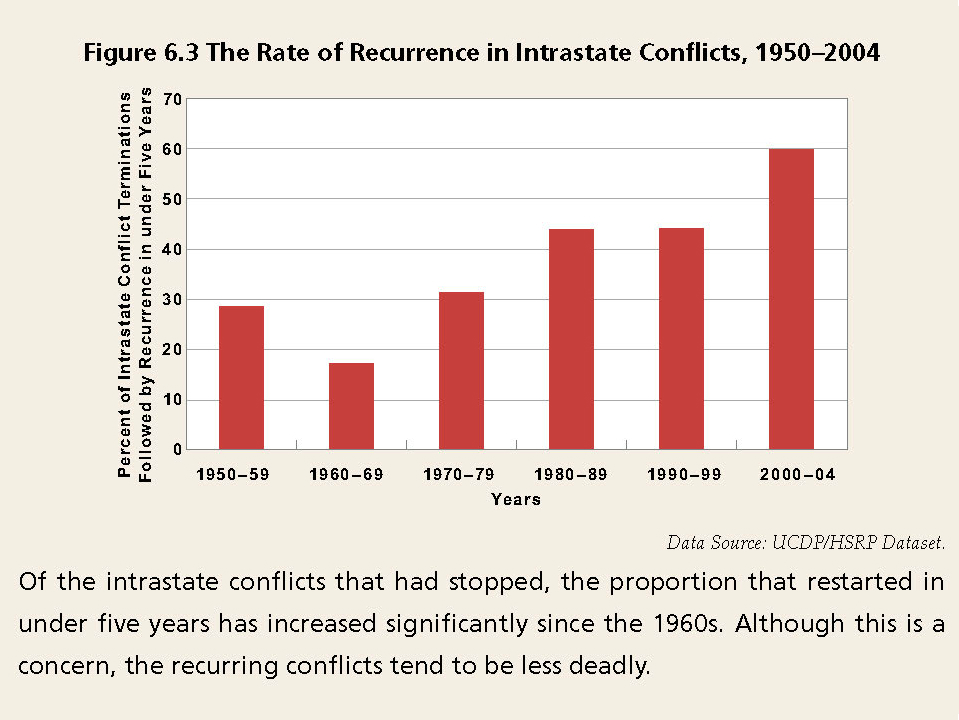

Conflict relapse has become characteristic of today’s civil wars. The UCDP armed conflict termination data clearly demonstrate that a substantial number of today’s conflicts are “on-and-off affairs”59 and that the recurrence rate of violent conflict is higher now than at any time since World War II: 60 percent of the conflict terminations between 2000 and 2004 were followed by renewed violence in less than five years.

Judging solely by the increase in the rate of civil war recurrence, we might be tempted to conclude that there is much cause for alarm. If, however, our major reason for concern about armed conflicts is the death and destruction they cause, then a closer look at the data on conflict recurrence reveals that the trend has some reassuring elements. Most importantly, as we explain below, it is very often the case that the conflicts that recur are relatively small and less deadly, not the ones that are responsible for the majority of battle deaths.

In 2011 the WDR observed that the overwhelming majority of the conflicts currently active are recurrences of violence. In fact, the report finds that “every civil war that began since 2003 was in a country that had a previous civil war.”

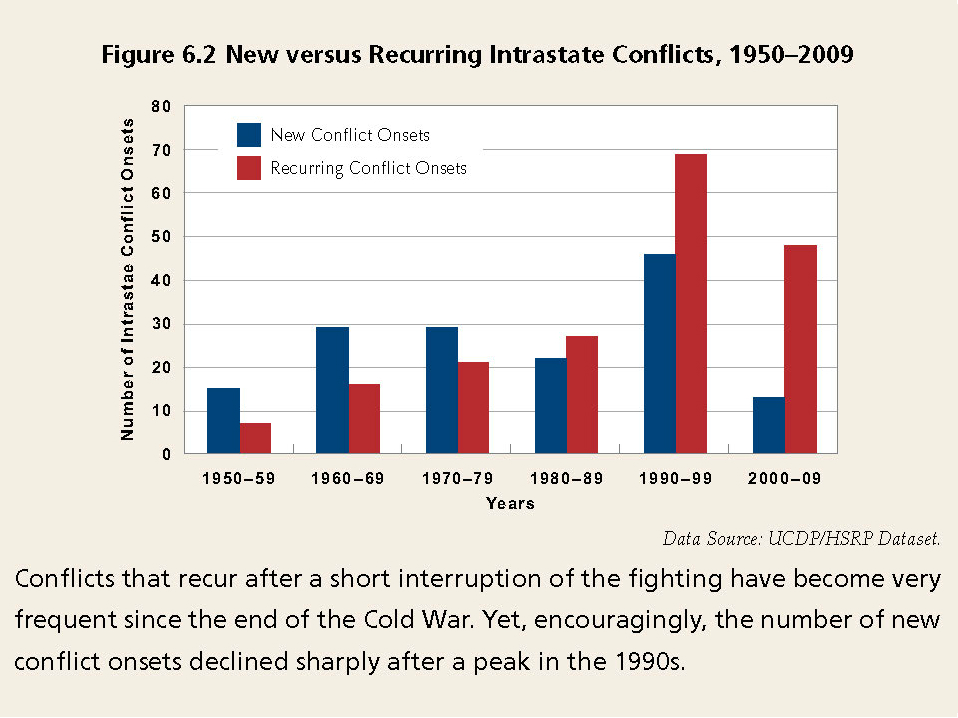

Figure 6.2 confirms this finding by presenting a similar measure. The number of onsets of new conflicts—i.e., conflicts that have not been recorded before—was lower between 2000 and 2009 than in any other decade in the post–World War II period. Outbreaks of new conflicts peaked in the 1990s, with 46 new conflicts, and dropped to just 13 in the first years of the new millennium, a reduction by more than two-thirds. Although the number of old conflicts erupting into new episodes of violent conflict dropped by about one-third over the same period, this number remained at a very high level. The share of recurrences for the years from 2000 to 2009 exceeded those of the Cold War decades by a factor of roughly two or more. Recurrences of earlier civil wars now make up almost 80 percent of all conflict episode outbreaks.

Not all of the messages that Figure 6.2 conveys are cause for concern. On the positive side, the drop in the number of new outbreaks of conflict suggests that fewer disputes, whether over territorial autonomy or over who should control government, are turning violent. If instead there was a larger number of new conflicts today, this would certainly be bad news for prevention efforts.

What is more, we have to keep in mind that for a conflict to recur, it first has to stop. The large number of recurring wars must therefore also be seen in the context of the many conflict terminations since the late 1980s. The fact that so many conflicts have terminated is encouraging, but this naturally resulted in more post-conflict settings that always involve a risk of violence recurring.

But the increased number of episodes where violent conflict recurs after a lull remains a concern, because it indicates that terminations of intrastate conflicts have become less stable. The proportion of terminations that are followed by renewed violence in less than five years has shown a substantial and steady increase over the last 40 or so years. Figure 6.3 demonstrates that the rate of recurrence has now reached 60 percent, a more than threefold increase compared to the 1960s.61 In the first half-decade of the new millennium, the risk of recurrence increased by more than one-third compared to the 1990s.

Civil Wars Have Become Difficult to Win

Conflict episodes can end in a number of different ways, and some endings are far less stable than others. The prime reason why there is a higher rate of recurrence of violence today is that less stable types of outcomes have become—relatively—much more common. For reasons we explain below, this change is not as big a cause for concern as it may seem.

As mentioned above, the UCDP terminations dataset records whether a conflict episode ends in a victory or a negotiated settlement, which can be a peace agreement or a ceasefire. Conflicts that drop below the 25-deaths activity threshold without a settlement or the defeat of one party fall into the “other” category.

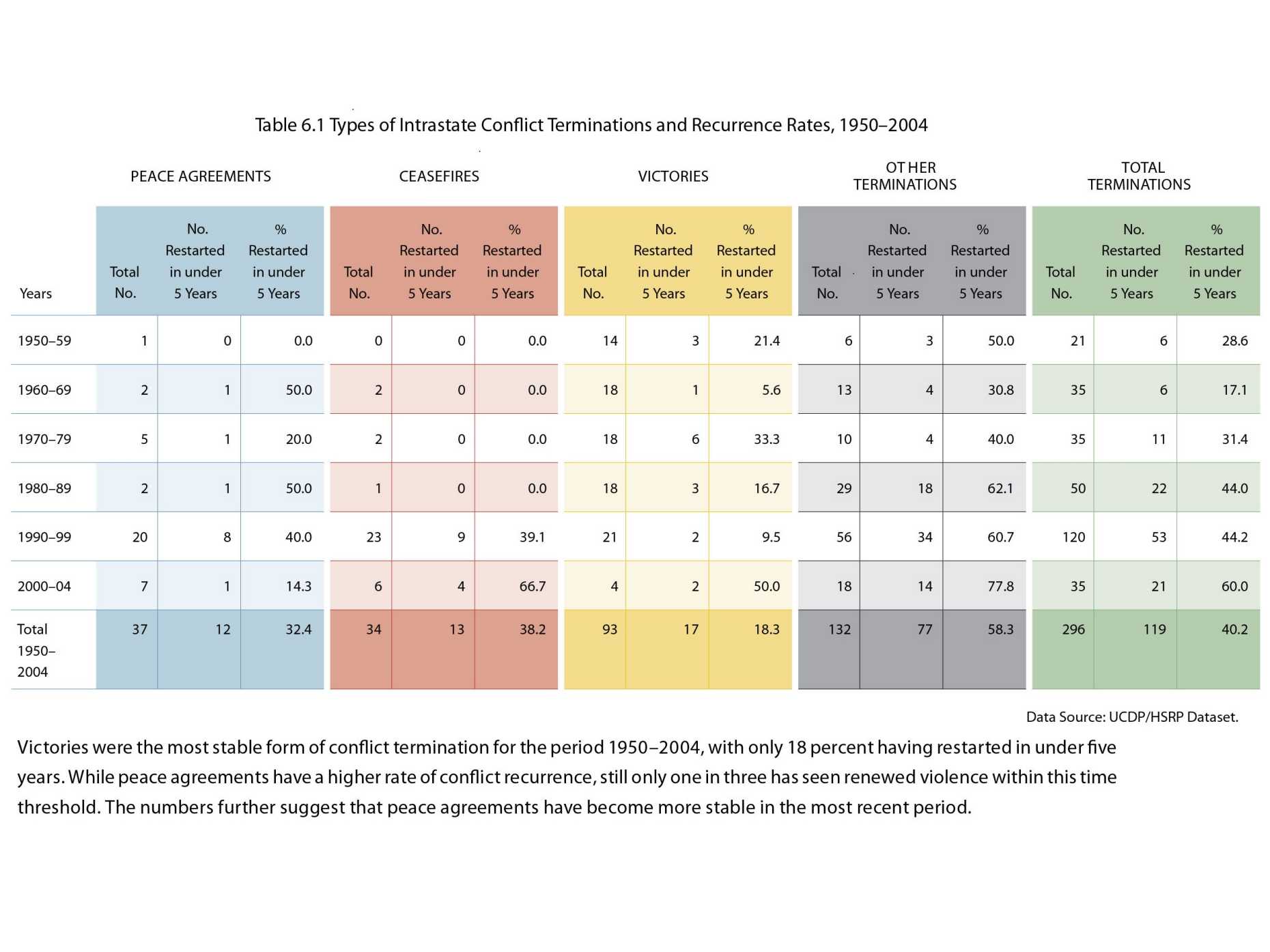

Victories have long been known to be the most stable type of outcome. Table 6.1 shows that between 1950 and 2004, less than 20 percent of the conflicts terminated by victories recurred in less than five years. In most cases, victory prevents renewed fighting because the defeated side simply lacks the capability to continue the struggle.

By contrast, where hostilities cease as a result of negotiations, both parties often retain their capacity to continue to fight. Given this, and given that the experience of war usually increases suspicion, fear, and mutual antipathy between the parties, it is not surprising that between 1950 and 2004, twice as many ceasefires (38.2 percent) and nearly twice as many peace agreements (32.4 percent) as victories (18.3 percent) were followed by renewed violence within five years.

Table 6.1 also clearly demonstrates that fighting is most likely to recur when a conflict episode ends with neither victory nor negotiated settlement. In most cases where a conflict dies down without a victory or settlement, there is merely a lull in the fighting, followed by renewed violence within a few years.

There are cases where conflicts taper off and do not start up again because the rebels quietly give up the fight. This happened, for instance, in Thailand, where the small communist insurgency ended in the 1980s. The rebels were not decisively defeated, nor was there a peace deal, but the conflict has not recurred since.

Yet, this is the exception rather than the rule. Between 1950 and 2004, almost 60 percent of conflict terminations that fell into the “other” category were followed by renewed violence in less than five years. The figure for the early years of the new millennium was nearly 80 percent.

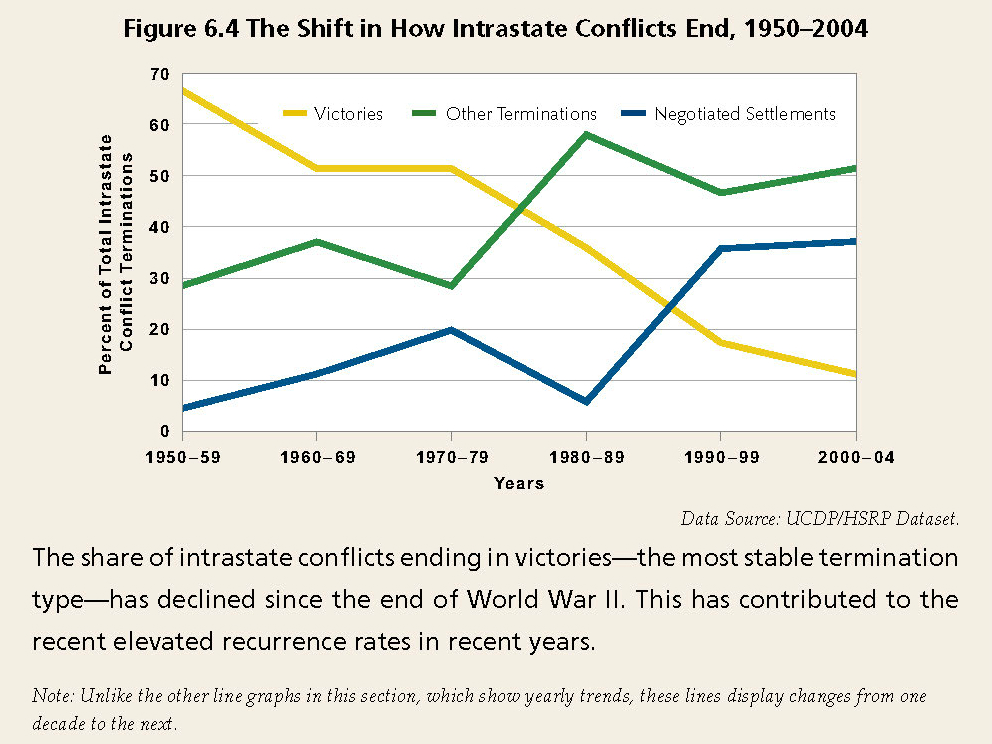

The data presented here show that the risk of conflict recurrence differs considerably for various types of conflict outcomes. But they also demonstrate that the relative frequency of these different outcomes has changed significantly over time. Figure 6.4 displays victories, negotiated settlements, and “other terminations” as a percentage of the total conflict terminations in each decade since 1950. It reveals a major shift over time.

Victories—the type of outcome least likely to be followed by a recurrence of violence— were by far the most common form of conflict termination from the 1950s through the 1970s. But civil wars have become much more difficult to win outright, and victories are becoming very rare. As Figure 6.4 illustrates, approximately only one in 10 of all terminations since 2000 has been a victory by one side over the other.

The decline in the number of victories has coincided with a fairly steady increase in negotiated settlements (ceasefires or peace agreements). As Figure 6.4 shows, for each decade of the Cold War period, the share of conflicts ending with a peace agreement or a ceasefire was only 20 percent or less. Since then, however, the share has risen to almost 40 percent.

Table 6.1 shows that in the majority of cases—68 percent for peace agreements and 62 percent for ceasefires—negotiated settlements lead to a stable solution of the conflict. But neither peace agreements nor ceasefires reduce the risk of relapse into violent conflict as much as victories do. That the increase in the number of settlements relative to victories has contributed to a higher overall recurrence rate is therefore no surprise.

Figure 6.4, however, indicates another major change: unlike during most of the Cold Wardecades, the majority of today’s conflict episodes end without a clear outcome. In the 1980s, “other” terminations surpassed victories as the most common type of outcome. Since then, roughly half of all conflict terminations have been “other terminations,” involving neither outright victory nor a ceasefire or peace agreement.

As explained above, these “other terminations” are far more likely to be followed by renewed violence. The change in how most conflicts terminate thus represents the single most important explanation for today’s high rate of recurrent violence. In fact, almost two-thirds of the recurrences since 1990 have been associated with “other” conflict terminations.

The data patterns discussed here clearly demonstrate that the rise in civil war recurrence rates is not because victories or negotiated settlements have become less stable over time. As we point out in the box on page 178-9, the data seem to suggest instead that peace agreements, at least, have recently become considerably more successful. There is also no clear trend for the stability of victories or for ceasefires. In other words, there is no general increase in recurrence rates of all types of terminations; instead, there is a change in the ways conflict episodes end.

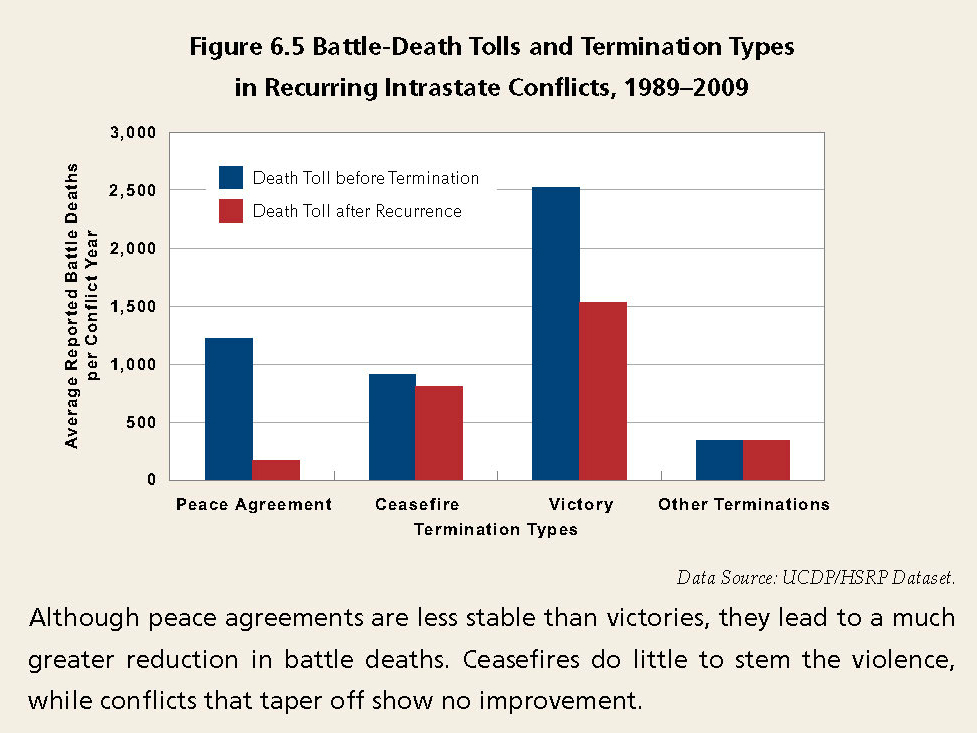

The Least Stable Terminations Occur in the Least Deadly Conflicts

Different types of conflict outcome not only have different risks of recurrence; they are also associated with different levels of lethality. Conflict episodes that end in victory are by far the most deadly. In a sense this is not surprising, since military defeats almost by definition mean large death tolls. By contrast, conflict terminations that fall into the “other” category, comprising the majority of all terminations today, have the lowest battle-death tolls. During the two decades since the end of the Cold War in 1989, the civil conflict episodes that terminated with neither victory nor a negotiated settlement had an average annual toll of less than 350 battle deaths. The toll is two times higher for ceasefires, three times higher for conflicts settled through peace agreements, and seven times higher for conflict episodes that ended in victory.

The comparatively small death tolls associated with the termination type that is most prone to conflict relapse suggest a link between low-intensity conflict and high recurrence rates. And there is, as we show below, evidence to support the view that the limited scope of conflicts can favour persistence.

We note that the definitions of conflicts and conflict terminations may partially explain the finding that low-intensity conflicts are more likely to stop and start up again. If a conflict only accounts for a few dozen codable battle deaths and thus hovers just above the threshold of 25 battle deaths a year, not much needs to change for it to be coded as inactive in one year and as starting up again in the next. A high-intensity conflict, on the other hand, killing 1,000 people per year, will require significant changes in the conflict dynamics for the toll to fall below 25 battle deaths.

If the high recurrence rate of low-intensity conflicts were only an artifact of the coding of the data, the finding would be of little value. However, there is evidently more to it. Research based on a new dataset indicates that contemporary conflicts significantly affect only a small fraction of a country’s territory. It is often these small conflicts that are also the most persistent conflicts of recent decades.

Thirty-eight percent of the conflicts that recorded three or more episodes over the last two decades had average death tolls of less than 100 casualties per year. These include the conflicts in Angola over the territory of Cabinda, the struggle between the government of Eritrea and Islamist rebels based along the Sudanese border, and the conflict over Tripura in India. Only four conflicts with more than two episodes—the conflicts over government power in Pakistan, Somalia, and in the Republic of Congo (“Congo- Brazzaville”), as well as the conflict in Sri Lanka—had an average annual death toll of more than 1,000.

Many of the conflicts with the highest number of cumulative years of fighting since 1989 are also of relatively limited scale, both in terms of intensity and geographical scope. India’s insurgencies in Assam, Manipur, and Bodoland have each accumulated between 15 and 20 years of conflict but resulted in average annual death tolls lower than 100. There are, of course, a small number of long-lasting conflicts that are also quite deadly, including the civil wars in Afghanistan, Sudan, and Sri Lanka, each of which has claimed more than 1,000 lives per year on average. But aside from these few cases even the more deadly persistent conflicts are usually limited relative to the size of the countries in which they take place. These conflicts typically do not engulf entire nations but are concentrated in smaller areas. Examples are the conflict in Northern Uganda, and in Turkey over Kurdistan.

This raises a question with important policy implications: why are small conflicts so persistent, in terms both of protracted low-level fighting and of high rates of recurrence?

The Persistence of Small Conflicts

We have seen that types of conflict terminations differ markedly in their rates of recurrence, and that the least stable outcomes and some of the longest-running conflicts are associated with very low death tolls. As we show in this section, there is a plausible explanation supported by recent scholarship: the smaller a conflict is, the fewer incentives there are for the parties to end the fighting.

Some conflicts are characterized by both persistence and a high intensity of fighting, as in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Somalia, and Sri Lanka. But many of the persistent civil wars active today are limited both in terms of human and material costs and the amount of territory affected by violence, because rebels often choose to base themselves in remote and inaccessible areas.

A number of recent quantitative studies show that small and peripheral insurgencies are more likely to persist. And some of the authors provide support for the argument that strategic considerations in the capital may be one reason for the persistence.

Fearon has argued that the reason these peripheral cases last a long time “may be that they involve relatively few combatants, pose relatively little threat to the center, and thus stay fairly small. They are difficult to eliminate entirely, and because they tend to be so small, not worth the cost of doing so.”

Guerrilla forces in remote areas are extremely hard to defeat. The Philippines Army, for example, possesses military resources that are vastly superior to that of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), an insurgent group mainly active in remote and mountainous areas. But, as in other small, guerrilla-type wars, the government’s problem is not so much defeating the rebels in battle, but locating and engaging them.

In other words, while peripheral insurgencies present little real threat, they are nevertheless difficult to put to an end. As a result, governments have few incentives to devote the resources necessary to end the insurgencies, either by military action or by negotiations.

There are additional reasons why state actors might not push forcefully to end low-level insurgencies. A state military organization, for example, may invoke domestic rebellion as a threat to national security in a bid to build its power base, or even to legitimize a coup against the government. Moreover, international actors are less likely to pressure a government to negotiate a settlement where the conflict is small and contained.

It is, of course, difficult for the quantitative studies cited here to determine what motivates the decisions of conflict parties, whether it is a government’s indifference or inability that presents obstacles to solving a conflict. But the argument that small-scale conflicts are allowed to persist because they do not significantly hurt the interests of the government side are consistent with findings from the qualitative literature as well. Chester Crocker et al., for example, point out that a state of war can become “a comfort-zone”81 when there appears to be an acceptable status quo—at least for those in positions of power on both sides.

Explaining Changes in Conflict Persistence

This chapter provides one of the first systematic analyses of trends in conflict persistence. Persistent armed conflict, we argue, can manifest itself in long, uninterrupted periods of fighting, as well as in intermittent conflicts that stop and start again frequently. We have therefore taken a closer look at patterns of conflict duration and recurrence.

First, we noted that the often-cited rise in the average duration of ongoing conflicts, while not untrue, is misleading in that it gives the impression that wars overall are becoming longer and more intractable. There are, of course, significant numbers of decade-long—and longer—conflicts that are still active today. These conflicts, understandably, receive a great deal of attention from researchers, which contributes to the impression that most conflicts are getting longer.

But while long-duration conflicts are a source of obvious concern, and while they inflate the average duration of conflicts, they remain the exceptions, not the rule. In fact, most of the conflicts that have started in recent years have been of short duration.

We point out that the rate at which conflicts restart after a brief calm has increased significantly. Today’s high recurrence rate, however, can to a large extent be explained by the trend towards small-scale armed conflict with few violent clashes that are often interrupted by months and years of tranquility.

As noted above, fighting in today’s conflicts tends to take place in confined geographic areas. The most persistent of these conflicts also result in low numbers of battle deaths and take place at the periphery of a country. And the data and research discussed above suggest that such conflicts are often allowed to persist precisely because the intensity and scope of the fighting is limited. Paradoxically, the very weakness of rebel groups may help them avoid defeat if it means that they carry out operations in peripheral territories where the violence and destruction they perpetrate do not represent a significant threat to the central government.

A second reason for the higher recurrence rate of conflict episodes today is the increase in the number of negotiated settlements. Since 1990 more conflicts have ended through negotiations than at any other time in the post–World War II era. Because such settlements have a significant risk of relapse into violence, any increase in their share contributes to a higher rate of conflict recurrence. Despite this, as we argue in more detail below, negotiated settlements are almost always the best available outcome for a conflict episode.

The picture we present is more encouraging than most other accounts of trends in conflict persistence. However, this is not to suggest that conflict persistence is a marginal issue. A significant number of persistent conflicts exist today and some of them are highly destructive. Responses to conflict persistence depend on reliable information about trends and what drives them. But just as important as understanding the causes of conflict persistence is trying to account for the positive developments over the last decades.

Why Most Conflicts Today Are Short-Lived

Global changes in the way conflicts are fought and resolved have had a profound impact on patterns of conflict persistence. Since the end of the Cold War, the intensity of armed conflicts has declined dramatically. In many cases, long-standing civil wars came to an end while new conflicts tended to end after only a few years of fighting. As a result, the number of conflicts has declined globally, but as we showed above, the duration of recent conflicts and conflict episodes has also seen a significant drop. The reduction in the intensity of armed conflicts, however, may have contributed to conflict persistence in other cases. As we have argued, some conflicts are able to persist precisely because their intensity is low so that they pose so little threat to governments.

For more than four decades following the end of World War II the superpowers and their allies engaged in “proxy” wars by fueling civil wars in the developing world. This exacerbated death tolls and prolonged the fighting by providing the warring parties with financial, military, ideological, and political support. The end of the Cold War abruptly reduced the external support that had helped sustain both governments and rebel forces. Without it, many long-standing conflicts simply ground to a halt.

With fewer sources of external support, the civil wars that started during the 1990s and 2000s became both shorter and less deadly. Few of the rebel movements active today have much chance of defeating the governments they oppose. Indeed, less than 5 percent of terminations in civil wars since 1990 have been insurgent victories.

The reduction of superpower support following the end of the Cold War affected rebel groups but also states. It is often claimed that conflicts persist because weak or “failed” states simply lack the capacity to end them. But they may also persist because governments are much stronger than insurgents, pushing the latter towards the periphery and out of reach of government forces. Where threats to a state are low because rebels are weak, but the challenges of crushing a peripheral insurgency are high, governments may prefer the low-cost option of containing the insurgency, rather than the high-cost route of seeking to defeat it.

The Successes of Peacemaking and Peacebuilding

The end of the Cold War also coincided with an upsurge in peacemaking and peacebuilding missions seeking to bring armed conflicts to an end and to prevent them from starting again. The 2009/2010 Human Security Report explained how this international activism has helped reduce the number of active civil wars around the world since 1992. But a muchless- remarked-on benefit of these international efforts has been a reduction in conflict duration.

There is strong evidence that the mediation efforts central to post–Cold War peacemaking have shortened the average length of armed conflicts. Patrick Regan and Aysegul Aydin found in 2006 that “diplomatic interventions dramatically reduce the expected duration of a conflict. For example, the expected duration for civil conflicts that have experienced diplomatic interventions is reduced by about 76 percent over conflicts without diplomatic interventions.”

Abel Escribà-Folch explains that economic sanctions, which have also increased dramatically in number over the past 20 years, may be much more successful in bringing conflicts to an end than is usually assumed. His models show that sanctions increase the chances of civil war termination or, in other words, shorten the duration of conflicts.

The upsurge in international activism thus provides an additional explanation for the decline in conflict duration since the late 1980s that we have highlighted in this chapter. As internationally supported peacemaking initiatives have increased, negotiated settlements have become more common. But, as we point out above, such settlements have—by their very nature—a considerable risk of collapse.

Today’s high rate of conflict recurrence is to some extent related to the increase in negotiated settlements and therefore also to the success of peacemaking, which has helped create more post-conflict settlements, and hence more situations in which conflicts may recur. This raises an important question for policy-makers: does the high recurrence rate of civil wars put in question the success of international efforts to shorten conflicts?

Some observers have argued that because of the high risk of subsequent failure, negotiated settlements artificially prolong the fighting and exacerbate human suffering. By contrast, conflict terminations that result from the decisive military defeat of one of the warring parties are seen as a better outcome because the defeated party often lacks the capability to go back to war.90 Conflicts that end in the military defeat of one of the warring parties are not immune to recurrence. But, as shown above, only around 18 percent of victories were followed by renewed violence, making it the most stable type of conflict termination.

What then are the advantages of peace agreements as a means of bringing conflicts to an end? The evidence clearly suggests that despite their risk of collapse, negotiated settlements almost always present the best available option to end wars and save lives.

First, negotiations may be the only practicable means of ending some conflicts. While victories tend to occur in shorter wars, negotiated settlements are usually needed to bring the longest-running conflicts to an end. Where a conflict is stalemated and victory has become unattainable by either side, the only alternative to a negotiated settlement is continued warfare, perhaps interrupted by short breaks in the fighting. Such “other terminations,” as we show above, are even more likely to be followed by renewed violence than negotiated settlements.

In other words, negotiated settlements do not prevent victories that, according to some scholars, would occur if a conflict was allowed to follow its “natural course.” Instead, settlements typically stop those conflicts that are stalemated and unlikely to be resolved through any other means.

In a small number of cases, peace agreements end the fighting even though one side is on the verge of defeat; that is, when victory for the other side is a realistic possibility. These settlements are usually very stable, since they involve a dramatic diminution of the military capacity of one side and negotiations that give at least some concessions to the weaker party. The conflict in Angola is a case in point. In 2002 the government struck a deal with UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) after the rebels had been seriously weakened. Since then, UNITA has transformed into a political party and no fighting has recurred in this conflict.

Last but not least, it is seldom recognized how much the costs of conflict are reduced by peace agreements even when they break down. The focus on conflict recurrence has drawn attention away from a crucial fact: the analysis in the box on page 178-9 points to the crucial, but largely unnoticed, finding that even peace agreements that break down almost always lead to a dramatic reduction in battle deaths. Death tolls drop by more than 80 percent on average in conflicts that recur after a peace agreement. This is a greater reduction than for any of the other termination types.

It is true that peace agreements have repeatedly failed to bring about an enduring peace and that this pattern may be repeated in the future. Yet, the evidence presented here clearly shows that peace agreements are often the only available option to raise the chances of peace and decrease casualties in persistent civil conflicts.

Moreover, there are ways to increase the success rate of peace agreements. Reaching and implementing a peace settlement demands a high level of cooperation and trust from the warring parties, yet such sentiments are usually absent in wartime. And, as Barbara Walter has argued, a peace deal usually “offers enormous rewards for cheating and enormous costs for being cheated upon.” She argues that this is why security guarantees from outside actors like the United Nations are crucial for reducing the risk of cheating and thus limiting the risk that conflicts will break out again.

UN peacemaking and peacekeeping missions have been shown to be successful at helping to end civil wars and preventing them from restarting. Both effects have the consequence of reducing conflict persistence. But even though peacemaking and peacebuilding efforts have grown rapidly in number since the end of the Cold War, they address only a limited number of conflicts.

The UN tends to deploy peacekeepers to high-intensity conflicts in relatively weak states. Many other conflicts—those on the territories of major powers and major regional actors, as well as small-armed struggles—receive little or no direct attention from international actors. This is not likely to change in the future. New research, however, suggests that in these cases, potential improvements in the quality and legitimacy of governance within the conflict affected state may also reduce the probability of conflicts recurring. There are many fragile and conflict-affected states where there is little prospect of a peace operation being mounted but where the international community may still work with national leaders to help them enhance the quality and legitimacy of their governments.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Reasoning with Rebels

Talking to the Other Side

Towards a Non-State Security Sector Reform Strategy