Border Theories and the Realities of Daily Public Exchanges in North America

24 May 2013

By Manuel Chavez for Slavic-Eurasian Research Center

This paper expands initial theory building focusing on borders in North America. While arriving at a complete theory is still challenging, this paper provides another building block towards its construction by adding the role and influence of the media. Sharing borders with the United States requires unique frames of interaction from Canada and Mexico and that generates different models of interface. Despite being friendly neighbors, the three North American countries engage in complex and interdependent activities that go beyond institutional and official contexts such as trade, energy, environment and security; in fact, the richness of the interaction is due to the intensity of social, cultural and familial relations as constantly presented by the media. As power is shaped and reshaped in North America, this paper examines and adds the role of the media to the next level of theory construction in order to understand its influence on border communities and national governments.

Introduction

Studying the North American borderlands reveals the growing multilayer of social, economic and political forces, their interconnected dimensions with each other, and a constant increasing complexity. More importantly, in the study of the region some disciplines have dominated the field, while others have been absent. The situation in North America (Canada, the United States and Mexico), is becoming more complex and difficult to conceptualize. This paper, first illustrates how interactive and interdependent the borders are in North American to underline the deep and constant interdependence of the three countries with each other. Secondly, the paper contextualizes the realities of tri-national interdependency under conventional theoretical models used to explain their reality. Finally, adding the critical elements of information and communication, the paper provides a theoretical model that helps in continuing the study of the region.

As the North American border becomes more complex and interdependent, this paper uses the central tenants of territoriality, sovereignty, interdependence, and now national security to interpret it. The interaction of all of these elements is fundamental to strengthen the North American border concept. In other words, the traditional core elements of nation-state, while very current in the region, need to add the intensity of economic and social interactions between the United States and its two neighbors; as well as the role of information exchanges.[1]

National security principles and policies of the United States, that for more than a hundred and fifty years were not considered in the region, came to assume a prime role after the September 11 terrorist attacks. The incorporation of national security in any model attempting to explain the realities of twenty-first century North American border region is now fundamental. New pressures cause significant challenges, specifically on the conditions of the U.S.-Mexico border, that include heavy immigration inflow patterns and policy controls and, for the moment, drug violence that is the result of a trafficking war.

Interdependent and complex models of interaction include a complex set of variables that function actively between nations sharing borders or intense relations.[2] In the case of North America, for instance, demographic changes and natural resources management are some of the critical and fundamental variables to consider. After the definition of borderlines with Canada in 1821 and with Mexico in 1848, the border areas evolved years later as the countries become more interactive with each other. The interaction of Canada with the U.S. has been more intense because most Canadians live within 100 miles from the border, and secondly because fresh-water resources located across the border served first as major transportation network and then as a major source of energy from the end of 1800s until today.[3] In the case of Mexico, historically most of the population has concentrated in the central-southern parts of the country not on the border. For the most part, the border was simply a port of entry in each direction that has been maintained with the corresponding low or high flows of traffic depending on the social, political, or economic conditions of each country. Natural resources are less available and demand more shared management on the U.S.-Mexico border, for instance, water sharing is complex since most of the topography is desert, and water is regionally scarce. Energy and oil are important but are mainly located on the eastern side of the border; yet, they have been critical in the bilateral relationship since the 1920s. [4]

The current structural conditions of interdependence between the United States and its neighbors are not bound to decline or to reduce in significant ways; in fact, they are expected to increase as the regional economy improves. Currently, the economies are emerging from the global Grand Recession with different patterns of recovery, the U.S. more slowly as result of its dramatic decline in real estate, financial institutions and manufacturing; and, Canada and Mexico more steadily as a result of less exposure to those economic sectors.[5] Despite the global crisis, Canada has been able to buffer the impacts with its diversified economy and heavy energy production; likewise, Mexico has been able to minimize the impacts by continuing a steady export platform of agriculture and oil production.[6] The United States, Canada, and Mexico are entering a period of cementing the current conditions of economic and commercial exchange through the expansion of energy, trade, e- commerce, and government procurement. As manufacturing across North America increases production and the border becomes the nodal point, industrial sectors are looking for mechanisms to keep and increase investments. All of these are supported by an agreement of security and economic cooperation [7] that seeks the facilitation of every exchange taken place between the three countries.

To all of these known elements in the North American region, a missed element that needs to be included is the role of the media and communication. In the formulation of theoretical approaches for North America it is essential to examine the large connections between people’s learning, their influence and opinion, and their institutions. People living in communities in North American border areas have daily exchanges with each other (whether they are direct or indirect), institutions also interact with each other, and people’s daily living is a result of how communication and information flows and is exchanged. Moreover, their local or national policies are not created in a vacuum; they are the result of the influence and mobilization (or lack of) of their civil societies, individual or partisan actors, and the role of the media. Local and community leaders, political party organizations, and neighborhood associations have a role to play in their domestic issues that many times are international in context and substance.

The media role is particularly important because by understanding its position, processes, and outcomes it becomes clear how information flows, how people learn, how information is shared and exchanged, and how all of these create public opinion. Public opinion in turn influences policies that have impacts on communities and localities that, in the case of borders, matter not only to the communities inducing change, but to their neighbors across border lines. So, this paper and its theoretical formulation propose to add to the current models of analysis the context and influence of the media.

The North American Complex Economic Interdependence

The rapid expansion on the Mexico border areas started with the 1963 creation of the Border Industrialization Program that was intended to create assembling plants for American companies. This program expanded dramatically from the 1970s to the 1990s as regionalization accelerated, and the two countries became more interdependent on each other.[8] By 1988, Canada and the U.S. signed a free trade agreement and Mexico started its corresponding negotiations with the U.S. As the three countries saw a possibility to benefit regionally, the countries created the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993.[9] Since then the three countries have increased their economic relationship to the point that Mexico and Canada are the two largest trade partners of the U.S., and for them, the United States represents their top world trade partner.

NAFTA sought to increase free trade, reduce tariffs and duties, and to create a regional economy that emphasized competitive advantage and transportation benefits. As interactions expanded, border needs also increased. During this period, most border protection and regulations were shaped on the basis of volume and fluidity of traffic of goods and people, but not security. Yet, September 11 brought a new dimension; national security trumped everything else to the point that in 2005, the three countries signed the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (SPP).

Despite the stringent U.S. border security regulations, North America is a vibrant and active region that continues to have high flows of vehicles, trucks, and persons across the borders shared with Canada and Mexico. Since the passing of NAFTA, trade has increased steadily from $297 billion in 1994 to $1.1 trillion dollars in 2008 or an increase of 270 percent. The trade volume for goods and services in 1994 was $813 million traded daily; however, by 2008 the total volume of trade between the three countries was $3.02 billion every day.[10]

Up until September 2010, trade has maintained a level of more than $2.6 billion per day. Mexico and Canada as top trade partners of the United States account for close to one-third of the total U.S. trade.[11] Moreover, trade in North America will most likely increase as energy, deregulated financial and insurance services, and government procurement grows in the coming years.

However, as national security measures by the U.S. Homeland Security became more stringent, cross-border trade slowed down. The movement of goods into the United States after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, became a security challenge to ensure an expedited and “trusted” system. Even though U.S. borders with Mexico and Canada were not closed during that day and the days after, the filters and controls implemented on the inspection points created following September 11 almost paralyzed trade between the these countries.

Table 1 U.S.-Mexico Border Inspections by Category 2009

Buses

Trains

Trucks

Personal Vehicles

Passenger Personal Vehicles

Pedestrians

TOTAL

2009

2,657,644

574,299

4,291,465

70,304,756

141,016,993

41,314,685

260,159,842

Pct.

1.02

0.22

1.65

27.02

54.20

15.88

100.00

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation. RITA. 2010.

Increased trade between the United States, Canada, and Mexico translates to a high number of inspections taking place on the borders. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security implemented daily around 720,000 inspections on the U.S.-Mexico border (See Table 1) that for the most part were persons (passengers or pedestrians). 78 million vehicles crossed the border, including personal vehicles, buses, trains, and trucks, which together represent about 213,000 inspections daily. This illustrates the magnitude of the infrastructure (human and physical) needed to facilitate and process the traffic that takes place every day on the U.S.-Mexico border.

The volume of inspections on the U.S.-Canada border is less voluminous but still requires significant infrastructure. As in the case of Mexico, inspections from Canada are higher for passengers of personal vehicles entering the United States (See Table 2). Yet, in comparing data from both countries, Mexico registers more yearly crossings that result from double the number of personal vehicles, almost triple the number of passengers, and 110 times the number of pedestrians. Only trains and trucks traveling between the United States from Canada were reported higher than those traveling between the United States and Mexico.

Table 2 U.S.-Canada Border Inspections by Category 2009

Buses

Trains

Trucks

Personal Vehicles

Passenger Personal Vehicles

Pedestrians

TOTAL

2009

116,355

1,553,416

5,020,633

26,698,239

53,508,568

379,902

87,277,113

Pct.

0.13

1.78

5.75

30.59

61.31

0.44

100.00

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation. RITA. 2010.

New Security Framework in North America

An important regional policy framework interacting continuingly is the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (SPP). Not much is known publicly about SPP in part because most of the elements in the partnership relate to security, intelligence and law enforcement. The other reason is that the news media has lost track of it because the partnership is segmented by multiple federal agencies and many areas of cooperation and collaboration lay under National Security regulations with restrictive information controls.

The partnership was signed in 2005, the SPP was touted as a positive instrument to increase the economic potentials of the U.S., Canada, and Mexico under a secure framework for people and communities. The three governments recognized officially SPP as a major facilitator to the social, economic, and political linkages already in place. Security, though, was the major tenet of the new partnership and was derived from the post-September 11 framework developed by the U.S. government.[12]

The partnership on security programs has implications for border areas (see Table 3) as the creation of biometric standards, cooperation of law enforcement and emergency agencies, sharing information and intelligence, and a program for “trusted travelers and goods.” These trusted travelers included the establishment and maintenance of the border programs NEXUS (the Northern Border Program), FAST (Free and Secure Trade), and SENTRI (the Southern Border Program). Also, the partnership proposed a new coordination model for the prevention, protection, and response of cross- border terrorism, cross-border health threats (including pandemics and endemics), and cross-border natural disasters.

Additionally, the new security framework proposed programs targeting border areas; others are of national and regional content (See Table 4). The United States, Canada, and Mexico agreed to increase border security programs that included biometric standards requiring governments to issue complying official documents by 2008. Areas of security included concrete steps to enhance cooperation of law enforcement agencies that included the sharing of information and intelligence as well as inter-agency collaboration.

One important role of cooperation is related to the prevention of and response to emergencies – regardless of their origin. After many years of marginal progress, SPP proposed programs and the collaboration of the three governments to control cross-border terrorism, and to manage cross-border health threats, and cross-border natural disasters. This area proposed the open communication and collaboration of federal agencies to respond to not only deliberate threats but to natural or health-related risks.

Table 3 Categories and Focus Areas of the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America

SECURITY

PROSPERITY

Major categories

-Secure North America from external threats

-Prevent and respond to threats within North America

-Further streamline the secure movement of low-risk traffic across shared borders

-Improve productivity

-Reduce the costs of trade

-Enhance quality of life

Focus

-Development of joint preventive, protective, and respond actions

-Intelligence sharing and screening

-Collaborative operations and law enforcement

-Facilitation for business operation

-Collaboration for business resources

-Safe food supply and joint controls for environment and health

Author’s analysis of the SPP-RL, 2005.

Table 4 Specific Areas of Collaboration under the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America

SECURITY

PROSPERITY

Content Areas

Traveler security Cargo security Bio-protection Aviation security Maritime security

Law enforcement cooperation Intelligence cooperation

Protection, prevention and response Border facilitation

Science and technology cooperation

Manufactured goods, sectorial, and regional competitiveness Movement of goods

E-commerce and Information and Communications Technology Financial services

Transportation Energy Environment

Food and agriculture Health

Total Areas

10

9

Author’s analysis of the SPP-RL, 2005.

Despite the focus on security, economic sectors are included in SPP and those considered as priorities to the regional North American economy include food and agriculture, energy, manufacturing (steel and auto), environment, transportation, and finance. These sectors are good examples of interdependence and positive governmental cooperation that needs to be public, explicit, and transparent. Under the energy sector, for instance, SPP proposed the expansion of science and technology in North America, the cooperation on nuclear facilities and materials, and the standardization of rules for regulatory cooperation. In addition, the energy sector considered the cooperation necessary to trade safely natural gas and oil and to increase efficiency in the entire sector. This is critical since Canada and Mexico are the two main suppliers of oil to the U.S.[13]

The Transition of Theoretical Constructions on Borders

Currently, there is no central paradigm of border studies and that results in mixed news. First, border research is still evolving and the development of a single border theory is still a work in progress as additional elaboration, conceptualization and formulation is taking place. For the most part, border research is a collection of theories that have application to certain geographical regions, but not on others; and similar phenomena can be explained by two different and opposing perspectives depending on the discipline. And second, as forces of global interaction evolve and mature, borders have direct or indirect impacts that provoke constant changes. To arrive at a border paradigm will depend on the stability of political and international forces and processes, but those again have a high degree of variance.

Scholarly research started examining borders with a disciplinary focus dominated by geography, and the unit of analysis as the physical boundaries that separate nations, states/provinces, and counties/cities. This beginning was part of a colonial process to demarcate the territories of the nineteenth and early twentieth century empires. As border lines changed with decolonization, geography followed the new boundaries and it studied the human, economic, political, and natural resources and movements located on those areas.[14]

History also had a significant role in border studies, as historians documented the social, economic, political, legal and cultural experiences of settlements on old and new boundaries. Historians were some of the first to bring attention to the consequences, not always positive, of the new redefinition of border areas. This was particularly important during the nation-state border changes in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. The historical analysis also included the very critical role of government, as they reminded us that changes did not happen without the strong hand of governmental power.

As boundaries were analyzed, legal frameworks were integral in the examination of borders. As borders have a definite place and their processes, characteristics, morphology, and changes had impacts on jurisdictional legislation they were placed under the realm of international, state/province, and municipal regulations.[15] Consequently, geography, history, and law were among the first disciplines that set the basis for the understanding of borders.

As other social sciences evolved more methodologically and theoretically, disciplines such as economics, political science, and international relations, attempted to understand and examine borders. The contributions of sociology and anthropology later were particularly important as they emphasized two major elements: agency and structure. Despite the natural boundaries of each discipline, for the most part, social sciences maintained that borders were understood as integrated elements, and consequences, of location, sovereignty, and territoriality.

As border studies began to examine more closely people, governments, social institutions and their influences, interactions, experiences, transitions and movements, the scope of analyses expanded and became more inclusive. That was the stage when subfields of the social sciences and interdisciplinary approaches arrived to study borders with specific foci: demographic changes, trade flows and impacts, environmental constrains, transportation patterns, transboundary interactions, and government conflict and cooperation models.[16] The arrival of the humanities and literary areas also helped to understand the manifestations of culture and identities on borders. All these disciplinary arrivals provided a more comprehensive empirical and theoretical framework to study borders with a multi and interdisciplinary focus that brought new light to the field.

Adding and combining the methods of other disciplines allowed scholars to examine borders as systems where social, economic, and political forces interacted in multiple levels. With this influence, the analysis of borders amplified significantly as new empirical models brought new lenses to examine borders. But this process was not the result of a concerted epistemological discussion of border scholars, it happened naturally as some borders become more hermetic or others more open. Likewise, rapid technological advances impacted borders making them more flexible, permeable and vulnerable. One discipline that now is bringing its long scholarly tradition to border studies is communications and its subfields of journalism, public relations, telecommunications, advertising, and health and risk communication.

First, border scholarship for the most part has not incorporated communication, or its subfields into its methods of study. It has not addressed how people living in border areas are informed and learn about the issues that affect their own communities, families and friends. As borders become more complex and interdependent, the role of communication cannot be ignored from the human, institutional, and governmental interaction that nations experienced. For instance, the role of newspapers, radio, TV, and social media is fundamental in understanding how borders interact with each other, think about each other, live within its boundaries, and mobilize to protect their interests.[17]

Specifically, three points of emphasis lie at the intersection of borders and communication: intercultural communication, cross-cultural communication, and international communication. Each of these deserves attention when considering advances in border theory construction. For instance, as nations interact actively with their neighbors across common borders, conflicts, misunderstandings and stereotypes can be reduced as governments use the media to influence positive public opinion with a model called public diplomacy.

Of all forms of communication, the media is the essential means by which information is provided to people about their communities and its role is more fundamental when the outlets are located in border areas. As individuals communicate with each other, the media influences their frame of reference. When border communities embark on communicating with each other their major source of information is the media. Consequently, the border news media takes advantage of their natural two markets, one on each side of the border, to provide information on what is important first for the local niche and then for the market across the border. Border media responds to the three major frameworks of communication. Reporters, journalists and editors exchange communication face-to-face with sources and advertisers on the other side of the border representing intercultural communication. Likewise, printed or broadcast media, first transmit traditional communication targeted to their traditional audience, then exercise cross-cultural communication by presenting the values and norms of one nation to the other, and then provide international communication derived from institutional and governmental information.

The three major components of communication (intercultural, cross-cultural, and international) are at play on the North American border every day. Intercultural communication takes place as communities and individuals communicate with businesses, schools, governments, families and friends on a daily basis. In areas with border twin cities this face-to-face communication occurs 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Cities on the U.S. Mexico border such as Tijuana-San Diego, San Luis Rio Colorado-Yuma, Cd. Juarez-El Paso, Nuevo Laredo-Laredo, Reynosa-McAllen, and Matamoros-Brownsville and others with smaller populations interact and exchange communication on a daily basis. Similarly, on the U.S.-Canada border the exchange is comparable in areas such as Niagara-Buffalo, Sarnia-Port Huron, Cornwell-St. Andrews, Fort-Frances-International Falls, Windsor-Detroit, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The fluid and constant flow of commuters that interact with each other on a daily basis represents also an example of an intense degree of intercultural communication.

Similarly, businesses trading and transporting products across each side of the border communicate with each other daily. Cross-cultural communication takes place as the norms and values used by each national culture in their daily exchanges of communication permeate their frames and contexts. The formality of corporations’ interaction with other companies or with staff of the same companies but on the other side of the border is a constant exchange of communication functioning within the cultural frameworks of each nation’s staff. For instance, the auto industry, which relies heavily on daily production of vehicles and parts, offers cross-cultural training for their staff who interact with staff from other countries. In fact, even when English is the official business language, there is no assumption in the industry that internal and external communication will flow and be received in the way it was intended.

International borders exist because of the presence of a frontier or a limiting line of a jurisdiction, and for the most part towns, states, or provinces must interact and communicate with each other. International communication takes place when local communities are represented formally by cities and municipalities are required to attend to environmental, security, economic, cultural, educational, and logistical issues. Attending to these issues requires constant and effective international communication that can be formal, informal, official, and unofficial. Moreover, at the federal level, forms of communication tend to be more formal and official requiring protocols, formats, and processes that are part of their traditions in dealing with the bureaucracies of other countries. The best example is the communication used by diplomatic officials and consular personnel who interact with their counterparts in working about the issues that affect their respective countries. Likewise, NGOs, universities, and other organizations operating internationally communicate with similar institutions, communities, and social groups using formal and informal communication that, essentially, is international.

Building a North American Border Theory

As discussed previously, the United States has defined and determined the characteristics of the North American border, its limits, operation, and regulation. Canada and Mexico for the most part have only adapted to the new measures enacted by Washington, DC. After the passing of NAFTA the three countries started efforts to construct a fluid and unobtrusive border, however, September 11 came to change that. As national security superseded other areas, the United States increased controls on both sides of its borders, and the two neighbors have no other option but to adapt to the new unilateral regulations.

Many scholars believe that the intensity of globalization and regionalization that took place during the 1980s and 1990s would produce a relaxation of borders.[18] In fact, some talked about a process of deterritorialization that did not materialize completely.[19] The European Union, for instance, moved to reduce border controls that facilitate the transit of people and goods within their borderlines and frontiers. Even the United States before September 11 contemplated mechanisms to facilitate controls and inspections on its borders with Mexico and Canada.

However, while U.S. Homeland Security controls steadily increased, the levels of economic interdependence did not change, as showed in the previous sections. And here is where the characteristics of the North American border help in the conceptualization and formulation of a border theory. The theory considers human flows in North America regardless of how policy is implemented by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in each inspection. This is to recognize that DHS officials verifying each person’s documents will treat people with different questioning. While DHS will not implement a policy to discriminate on the so-called “hierarchy citizenship” or in their personal background, in practice, federal officers may apply their own personal discretion and biases to those who are citizens from other countries, naturalized citizens, permanent residents, and visitors. However, despite the discretion that DHS agents have to treat any individual, the social and economic forces will not reduce significantly the flows of people willing to cross borders.

First, North American borders exist in a model defined as complex interdependence, which was proposed by Keohane and Nye in 1989 (although originally they proposed the basic assumptions of their theoretical model in 1977).[20] This theory proposes that countries living at peace but with high levels of economic and social interaction are more willing to engage in cooperation and to reduce any military action to resolve conflicts. Countries that experience this model also exhibit a high degree of interaction between their societies. This is the case of both Mexico and Canada.

Second, despite some media generalizations that the Canadian and American borders are similar, the reality is far from it – they are different and distinctive. The U.S. and Anglo-Canadian border have some similarities but more differences since Americans and Canadians on both sides of the border are very determined to establish their own boundaries and identities, insisting that they are very distinctive. In addition, the case of the Franco-Canadian border region with the U.S. could not be more different, as the Quebec area imposes its own identity at and beyond any of their crossing points.

Thirdly, despite differences on the U.S.-Mexico border, the region has a strong context of binational and bicultural attributes. This is easily understood as most of the populations on the American side is of Mexican origin, ranging from 60 to 95% of the total per metropolitan area. [21] Border residents see themselves as being part of the border with the two identities coexisting. The culture of Northern Mexico and Southern U.S. exhibit a high degree of communality that includes language, traditions, food, music, folklore, and even architecture. In fact, the region is commonly known as the origin of Spanglish, a combination of both English and Spanish used in informal settings.

With these differences and commonalities and high levels of complex interdependence of the North American borders, the construction of a theoretical model is difficult to elaborate. However, there are very close formulations that offer a possible path to conceptualize a theory. The proponents of the theory are Konrad and Nicol (2008)[22] who advanced the original propositions of Brunet-Jeilly (2005). [23] Their proposition is simple and clear and represents the fluid and dynamic processes on the border. The proposed model in this paper builds upon their formulations to provide another stage of border theory conceptualization.

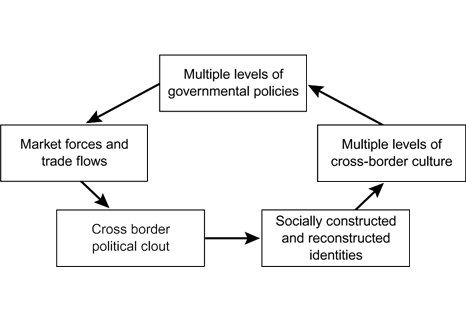

The Konrad and Nicol theory proposes an interactive process of five stages that follow a specific path: socially constructed and reconstructed identities -> multiple levels of cross-border culture -> multiple levels of governmental policies -> market forces and trade flows -> cross border political clout, and then the process repeats.[24] The stages are simply the forces that interact actively on the border that include identities, culture, government roles, economics, and politics. The model proposed here adds and edits some of their concepts.

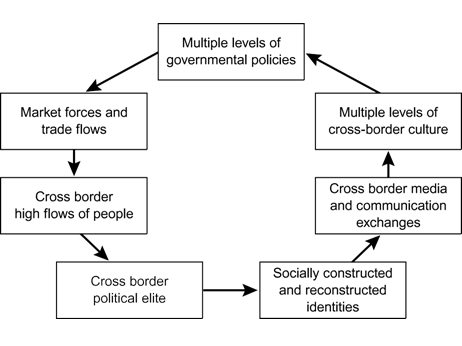

The model proposes to place in the second stage a new component called cross border media and communication exchanges and after market forces and trade flows, a new stage called cross border high flows of people. The editing is in the last stage to change the political clout for political elite so that it represents more precisely who is behind the power structure on border areas. As defined, this model would be as follows: socially constructed and reconstructed identities -> cross border media and communication exchanges -> multiple levels of cross-border culture -> multiple levels of governmental policies -> market forces and trade flows -> cross border high flows of people -> cross border political elite, and then the process repeats.

Figure 1 Konrad and Nicol Theory Model for North America

Socially constructed and reconstructed identities -> multiple levels of cross-border culture -> multiple levels of governmental policies -> market forces and trade flows -> cross border political clout, and then the process repeats.

Figure 2 Chavez Model Adapted from Konrad and Nicol

Socially constructed and reconstructed identities -> cross border media and communication exchanges -> multiple levels of cross-border culture -> multiple levels of governmental policies -> market forces and trade flows -> cross border high flows of people -> cross border political elite, and then the process repeats.

This conceptualization adds to the forces that interact actively on the border including identities, culture, government roles, economics, and politics, the very critical role of the media which is responsible for directing and influencing public opinion, and the recognition of high level of crossing flows of people. These stages are interactive and underline the importance of interdependence, cooperation and conflict derived from the volume and the intensity of constant interaction. In both areas of the border, the role of the media and intensity of people flows are elements needed to arrive at a more comprehensive border theory for North America. As in any other theory building, there is a need to provide empirical testing and for the moment the propositions of this theoretical framework are still under construction.

Finally a note on why violence is not considered in this model. The recent violence on the border related to the drug-war is a localized confrontation between Mexican drug traffickers to control the entry paths of drugs into the United States. The drug trade is confined to cities across the border and some central cities in Mexico, which are the places of operation of the drug leaders. Drug violence and its impacts on communities nearby the border, clearly is the result of drug interdependence between the United States and Mexico. In other words, the laws of supply and demand are at play as the U.S. is a heavy consumer of drugs and Mexico an active supplier of those drugs.

Currently, and according to intelligence analyses, the drug-war does not represent a threat to the binational relationship and it is not spilling onto the American side.[25] The two governments through the Plan Mérida (Merida Initiative) are cooperating in the eradication of production areas and in the arrest of leaders and members of drug trafficking groups. Ultimately, the best demonstration of cooperation and collaboration is that despite the violence, the two countries co-exist with each other for three hundred and sixty five days of each year.

Empirical research will help to apply and test some of the propositions of these models and will advance their further formulation. So far, these propositions respond to the current realities of North American borders, but as organic and dynamic as they are, a border theory will likely need to adapt to new, unforeseen realities.

[1] Silvia Nuñez-Garcia and Manuel Chavez (eds.), Critical Issues in the New U.S.-Mexico Relations: Stumbling Blocks and Constructive Paths (Mexico: National University of Mexico Press, 2008).

[2] Joseph Nye, Soft Power. The Means to Success in World Politcs (New York: Perseus Books Group, Public

[3] Roger Gibbins, Regionalism, Territorial Politics in Canada and the United States (Butterworths: Toronto, Canada, 1982).

[4] Oscar J. Martínez, Mexico Borderlands: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers [Jaguar Books in Latin America],1996); Oscar J. Martínez, Border People: Life and Society in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1994).

[5] Dow Jones Wires, “Nafta Reports Higher Revenues and Profit for 2010,” SITA Slovenska Tlacova Agentura July 15 2011.

[6] “Bringing NAFTA back home,” The Economist, October 30 2010, p. 39.

[7] Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (SPP), “Report to Leaders,” Governments of Mexico, Canada, and the United States, Printed Version (2005).

[8] Paul Ganster, “On the Road to Interdependence? the United States Border Region,” in Paul Ganster, Alan Sweendler, James Scott and Olf Dieter-Eberwein (eds.), Borders and Border Regions in Europe and North America (San Diego, CA; IRSC, San Diego State University Press, 1997).

[9] Manuel Chavez and Scott Whiteford. “Beyond the Market: Political and Socioeconomic Dimensions for Mexico,” in Karen Roberts and Mark Wilson (eds.), Policy Choices. Free Trade Among Nations (East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 1996).

[10] U.S. Department of Commerce (USDC), “U.S. Top Export Markets Report,” Free Trade Agreement and Country Based Fact Sheets (Washington, DC; International Trade Administration, 2010).

[11] U.S. Office of the Trade Representative (USTR), “North American Free Trade Agreement Report page,” http://www.ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/north-american-free-trade-agreement-nafta accessed November 15 2010

[12] See Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (2005).

[13] See Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (2005).

[14] Barbara J. Morehouse, “Theoretical Approaches to Border Spaces and Identities, ” in Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi, Barbara J. Morehouse and Doris Wastl-Walter (eds.), Challenged Borderlands: Transcending Political and Cultural Boundaries (London: Ashgate, 2004), pp.19-40.

[15] Manuel Gonzalez Oropeza, “La Internacionalización de la Frontera Mexico-Estados Unidos en el Marco Legal,” in Alfonso Cortez, Scott Whiteford, and Manuel Chavez (eds.), Seguridad, Agua y Desarrollo; El Futuro de la Frontera U.S.-Mexico [Security, Water and Development. The Future of the U.S.-Mexico Border] (Tijuana, Baja California: Colegio de la Frontera Norte Press, 2005).

[16] Paul Ganster, Alan Sweendler, James Scott and Olf Dieter-Eberwein, Borders and Border Regions in Europe and North America (San Diego, CA: San Diego State University Press, 1997).

[17] Bella Mody, International and Development Communication: A 21st Century Perspective (Thousand Oaks, and London: Sage Publishing Co., 2003), pp. 1-4.

[18] James Scott, Alan Sweendler, Paul Ganster and Olf Dieter-Eberwein, “Dynamics of Transboundary Interaction in Comparative Perspective,” in Paul Ganster, Alan Sweendler, James Scott and Olf Dieter-Eberwein (eds.), Borders and Border Regions in Europe and North America (San Diego, CA: IRSC, San Diego State University Press, 1997).

[19] Thomas Wilson and Hastings Donnan, Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers (Cambridge; Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[20] Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition (Boston: Little- Brown, 1977; 2nd edition, 1989).

[21] U.S. Census Bureau, “Preliminary Demographic Results” (Washington, DC, 2010).

[22] Victor Konrad and Heather Nicol, Beyond Walls: Re-Inventing the Canada-United States Borderlands (London: Ashgate, 2008).

[23] Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, “Theorizing Borders,” Geopolitics 10 (2005) pp.633-649.

[24] Konrad and Nicol, Beyond Walls, p.55.

.jpg)