Southern Africa RSC: The Polarity

24 Sep 2013

By Igor Castellano da Silva for Africa Institute of South Africa (AISA)

from external pageSouthern Africa Regional Security Complex: The Emergence of Bipolarity?call_made

As shown in the first section of this paper, Buzan and Waever emphasise that South Africa holds the regional unipolarity in Southern Africa RSC by its economic dominance over neighbours and the predisposition of regional states to accept its leadership. This section attempts to validate this proposition in the 2000s and to include, based on methodological guidelines of neorealist theory of International Relations, indicators related to material capabilities to evaluate the polarity of the region.

If it is sufficient to say, ‘that for the idea of polarity to work as a definition of the system level it requires a single, identifiable concept of great power.’ then it is also significant to consider a concept of regional power to access the polarity of the region.

For being a great power or a regional power, the main element that defines that quality is the existence of a substantial gap of power between the country in analysis and the countries within the level in question, global or regional. In short, what matters is the gap between the country aspiring to be a power and the rest.[39] This is the main element that sustained the evaluation made by Douglas Lemke of the regional powers in the regions he analysed in 2010.

The next open question is, ‘gaps in what terms?’ In other words, ‘what are the criteria/ elements which a country should present in excess compared to other regional members to be considered a regional power?’ For Buzan and Weaver as for Frazier and Stewart-Ingersoll, Nolte, Destradi, Nabers and Schirm there are two main groups of elements that should be taken in consideration. The first group comprises elements traditionally used by theoretical realism; the material capabilities. On the side of defensive realism, Kenneth Waltz highlights the distribution of material capabilities among the factors that compose the structure and consider factors such as territory, population, natural resources, wealth, military strength, political stability and competence as necessary qualities of a power that determine system polarity. On the side of offensive realism, John Mearsheimer argues that the ability of states to maximise power in the system relates to the availability of concrete power (military capability, especially armies) and potential power (population size and wealth). The second group is more linked with behavioural criteria, such as the formal recognition of a country as a regional leader and the necessity that political calculations of the regional members take into account the main powerful states.

Besides the importance of behavioural aspects to the establishment of a regional leadership and to consolidate a country as a regional power, one could sustain, as neorealists do, ‘identity and behaviour of regional powers should be determined by the regional distribution of these capabilities.’ In other words, the material capabilities are a precondition for those behavioural aspects to work properly. In practice, the behavioural criteria of Buzan and Weaver eventually led to the expansion of the concept of regional power and, consequently, to difficulties in measuring the degree of power of states and to establish a hierarchy between the elements. In the case of their own study they were careless about the evaluation of material capacities and focused on behavioural aspects with a low level of rigor and systematisation. In none of the region studies of Buzan and Waever is there a real assessment of the material capabilities of the regional members or comparative studies among the countries by using important indicators related to material capabilities.

In the case of the Southern Africa RSC, for example, that are many statements presented to support the proposed unipolarity based in South Africa, but no empirical evidence is shown. For instance, they have assumed that South Africa is ‘a giant compared to its neighbours’; a ‘regional great power’; ‘dominant to an unusual degree’. The country would have a ‘dominant position’; a ‘longstanding economic dominance’; and a ‘high percentage of resources of the region’. Beyond the supposed disproportional material capacities, for which the authors don’t present any concrete evidence, there’s also the behavioural argument. The authors suggest a ‘readiness of the other states in the region to accept South African leadership’. On the other hand, they paradoxically sustain that lately South Africa has ‘failed to provide regional leadership’, that there are some ‘mistakes in South Africa’s handling of its leadership role’ and some ‘difficulty of agreeing in practice on how to divide roles and responsibilities’ exists in the region. Those later statements may logically invalidate their own argument of the unipolarity, as their concept of regional power contains behavioural aspects, such as leadership.

Here, it’s not argued in favour of the elimination of the behavioural elements of power but we propose an example of approach to evaluate material capabilities and to use those elements as the primary task in power evaluation. In this section we propose to give a partial rigour to the identification of regional powers. Rigour because we intend to give empirical indicators that will sustain our arguments. Partial because we only focus on material capacities of the countries, an approach more aligned with the neorealist theory.

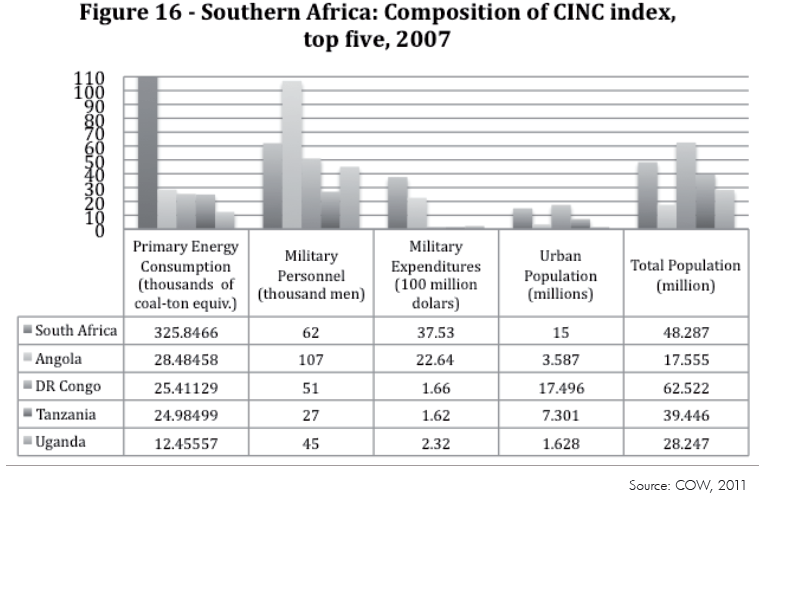

Among the material capabilities, those relating to the potential power (GDP and population) and concrete power (size of the army and weapons) may be mentioned. As the results will show, the polarity of the RSC seems directed toward an unbalanced bipolarity. South Africa has economic and military power disproportionately superior than all other countries, but Angola has stood out among the other countries in the region due to the puissance of its economic growth, size and experience of its armed forces and the experience acquired after the victory in their civil war and some stability operations in neighbouring countries.

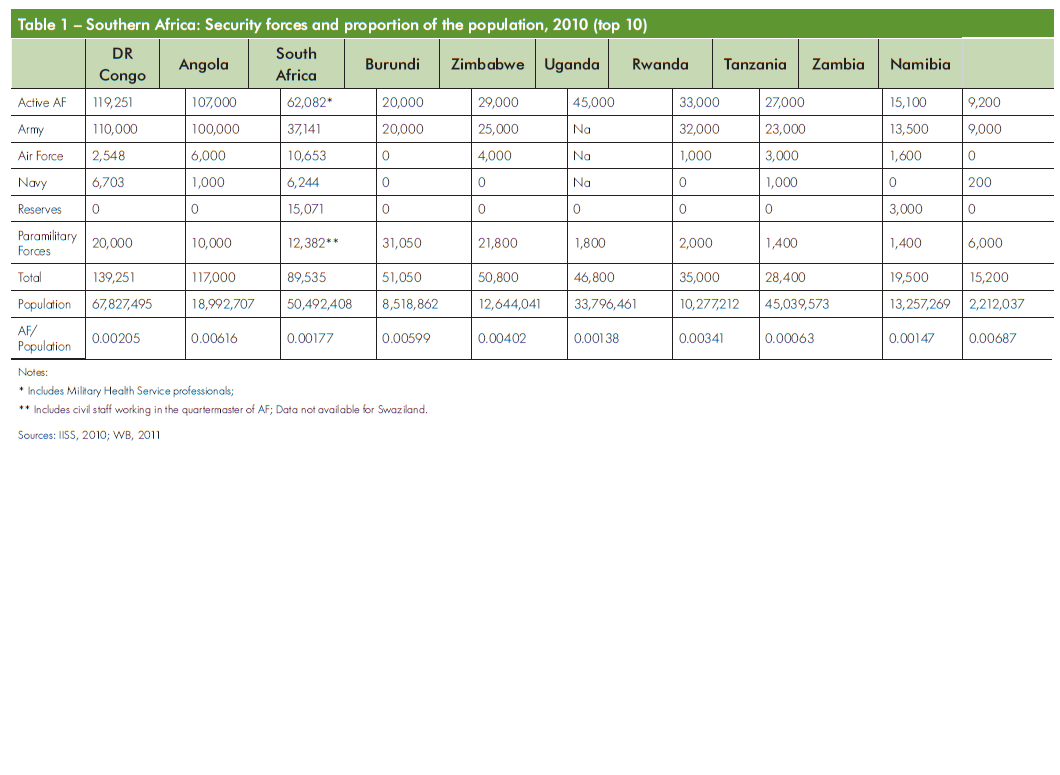

Table 1 -- Southern Africa: Security forces and proportion of the population, 2011 (top 10)

As an initial task, one seeks to assess the size of the security forces in the region (see Table 1). The first impression, however, is suggestive; South Africa does not have the largest security forces. It lies behind the DRC and Angola. The second impression is even more suggestive, the DRC has the largest security forces in the region with 140,000 men. However, it is worth mentioning that this number is totally misleading. There are two reasons for this; the first is that it represents a process of expanding of the Congolese Armed Forces, intensified in 2008 when the country’s total military contingent went from 51 to 120 thousand. This explosion in the number of troops was due to the beginning of a second phase in the integration process of the belligerents of the Second Congo War and the armed conflicts of the State of Violence into the national forces. The second reason results from the first; the Armed Forces of the DRC are typically ineffective. This is because the integration process was full of shortcomings, related to the scope of the programs and the scarcity of resources.[40] As a result, one of the great villains of the current ‘state of violence’ is a part of the Congolese Armed Forces itself which attacks national populations, plundering, murdering and sexually abusing some communities.

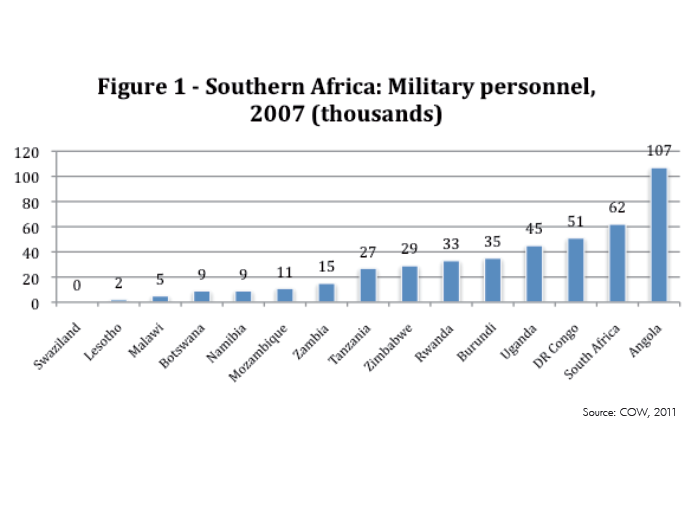

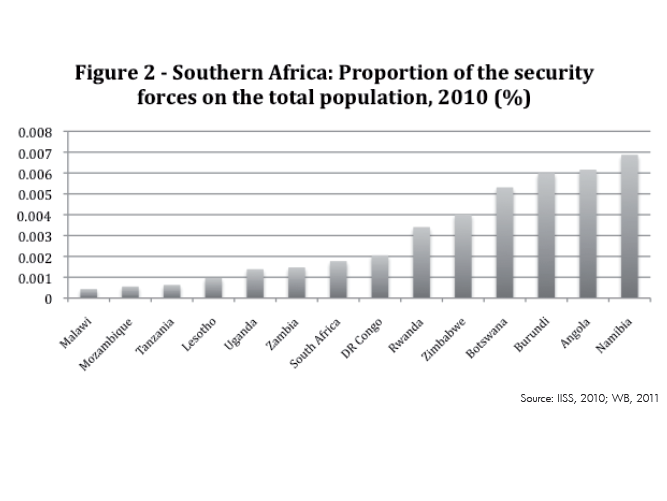

Thus, a figure more consistent with the reality of the 2000s is presented for the year 2007 (see Figure 1) in which Angola, and not the DRC, appears as having the greatest military contingent in the region. It is important that this fact remains true to this day, if only the forces effective and responsive to a chain of command and control are counted (C2). Moreover, currently, Angola has one of the highest proportions of security forces/population in the RSC (see Figure 2).

Besides representing the largest effective military contingent in the region, the FAA acquired considerable experience in recent decades with the clash of regular and irregular threats. In the case of conventional threats, we can mention (i) the SADF (South Africa Defence Forces under apartheid) in support of UNITA, (ii) the UNITA armed groups in battles adopted regular tactics and (iii) Rwandan troops during the Second Congo War. In the case of irregular battles, the guerrilla tactics adopted by UNITA in various moments of the civil war should be remembered, especially on occasions when they were at a disadvantage, as in the period after the year 2000.

In the case of South Africa, its last relevant conventional war was waged in Cuito-Cuinavalle, when a relative parity of forces in relation to Angola was observed. However, one stresses that Angola fought with the help of 20,000 Cubans and in its own territory. On the other hand, currently the main SANDF experience of war is with peace missions, which raise questions about its real ability to fight in regular combat.

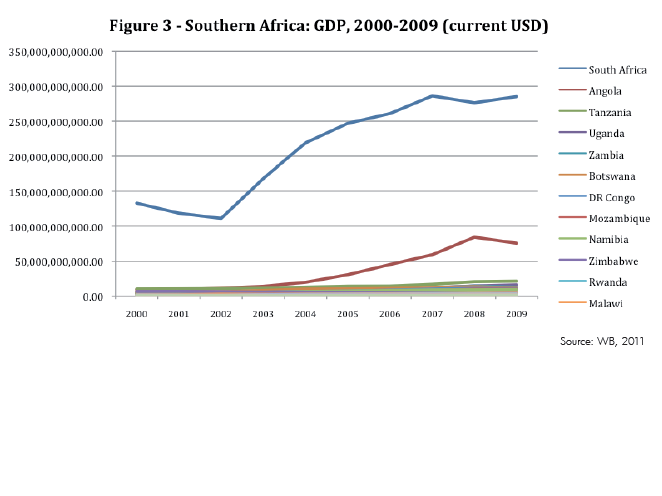

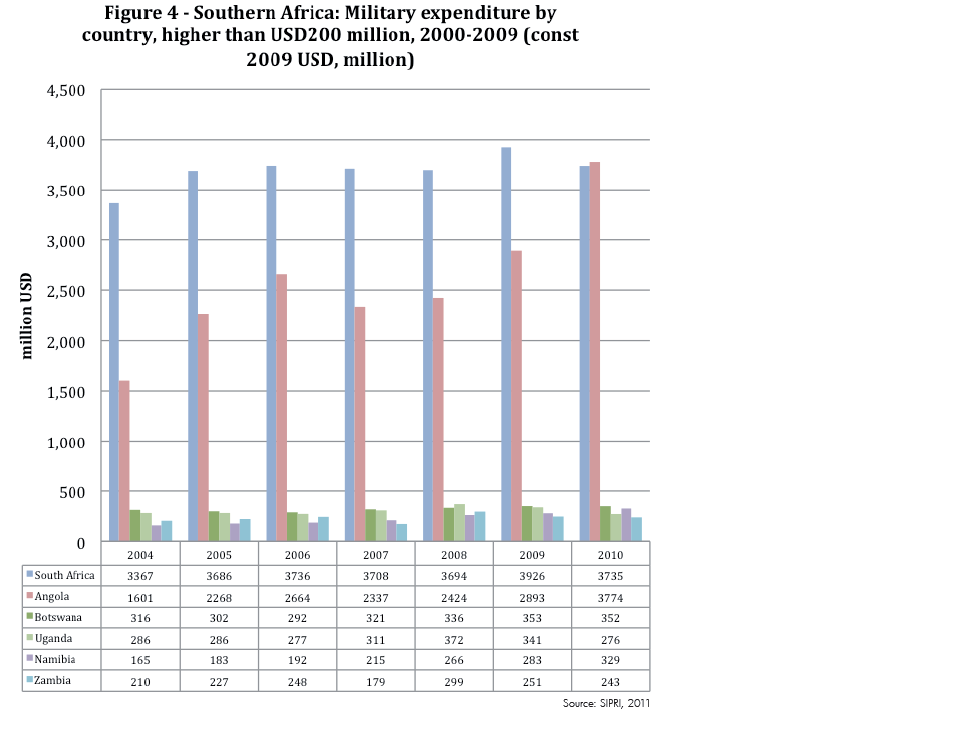

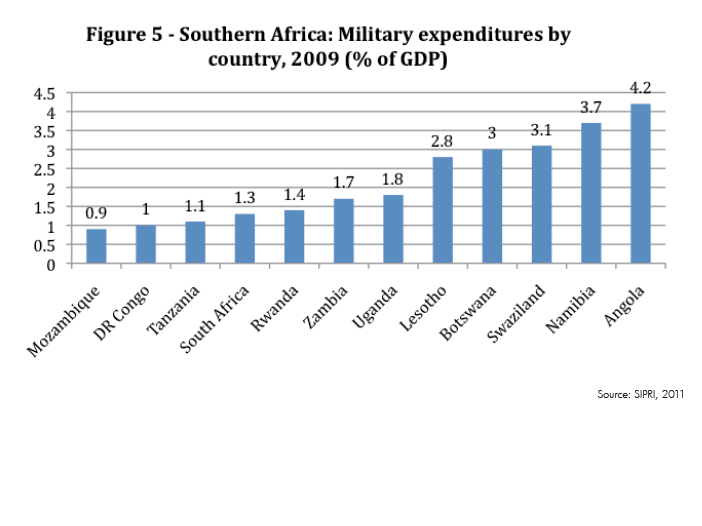

However, the economic superiority of South Africa in relation to its neighbours (see Figure 3) enabled the country to direct considerably higher resources to the defence sector during the 2000s (see Figure 4). These features favoured an important process of modernization of the Armed Forces conducted in the last decade, as discussed below. Furthermore, although there is economic and social pressures to control and reduce these costs in post-apartheid South Africa, the small proportion of these resources in relation to GDP (see Figure 5) would, at least in theory, leave space to an increase in expenditure in a sustainable manner (usually up to approximately 5% of GDP). This disparity in favour of South Africa is also found in other materials capacities evaluated below.

However, it is worth mentioning that, with an exponentially higher increase during the decade, in 2010 Angola’s military spending exceeded that of South Africa. In addition, throughout the decade the country has maintained a prominent position among other countries in the region. The data suggests that throughout the decade Angola, despite having an inferior position against South Africa, held important distinctions in relation to

other countries in the complex. With respect to absolute military spending (see Figure 4), excluding South Africa, all other countries of the complex (including those not represented in the figure) totalled together over the decade, only a little more than a half of Angola’s expenses. Angolan military spending growth during the decade was significant and in 2010 the sum of the expense of other countries was less than half of Angola. Specifically, in 2010 Angola had accumulated 42.14 per cent of expenditures in Southern Africa, South Africa had 41.72 per cent of the expenses and all other countries remained with 16.15 per cent.

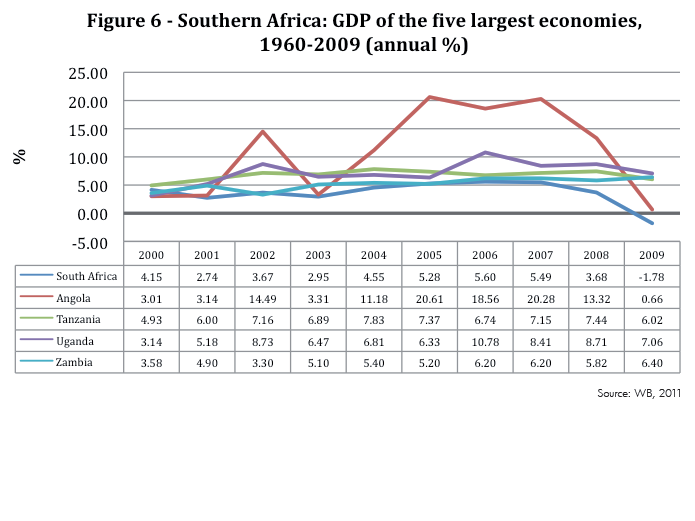

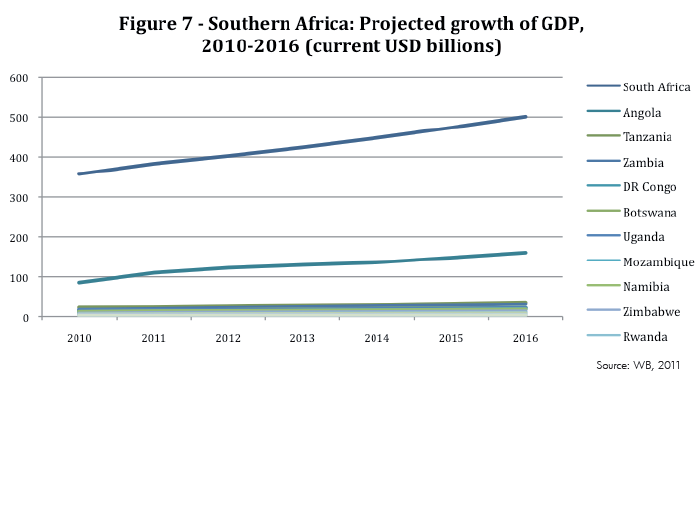

In regards to GDP, it should be remembered that Angola has recorded the highest growth in the region in the last decade (see Figure 6). The increase was also observed in the country’s absolute GDP. The Angolan national income accounts for more than three times the GDP of the next country in the ranking (see Figure 3), even considering the economic downturn in 2008. Furthermore, this ratio tends to remain constant at least until mid- 2010, according to the IMF (see Figure 7). The growth was also present in the country’s per capita GDP, which was US$ 4,081.22 in 2009, more than twice the average for the region (US$ 1,833.71) and relatively close to that of South Africa (US$ 5,785.98). However, it should be noted that economic growth in the last decade is centrally based on massive increases in oil prices and on the expansion of its exploitation. As a result, the increase in GDP per capita does not necessarily mean that there was some distribution of the national wealth. There is a fragile economic dynamism in Angola [41], while South Africa has a relatively diversified economy, but it has been hard hit by the crisis of 2008.[42]

With regard to military equipment, South Africa is disproportionately more technologically advanced, but Angolan largely exceeds the capabilities of its neighbours. Moreover, the equipment profile of the two countries differs with regard to the type of war and the doctrine adopted. On the one hand, Angola has a strength profile that combines mobility and regular capacity. On

the other, South Africa maintains a profile of force directed to participation in peacekeeping missions, which involves the need for prompt establishment of troops, and to national and regional defence against maritime threats (piracy and illegal fishing). These profiles have centrally influenced the process of modernisation of both countries’ forces in the last decade.

Angolan and South African military modernisation

Before describing the process of military modernisation which both countries have been through in the last two decades (qualitative analysis), one should

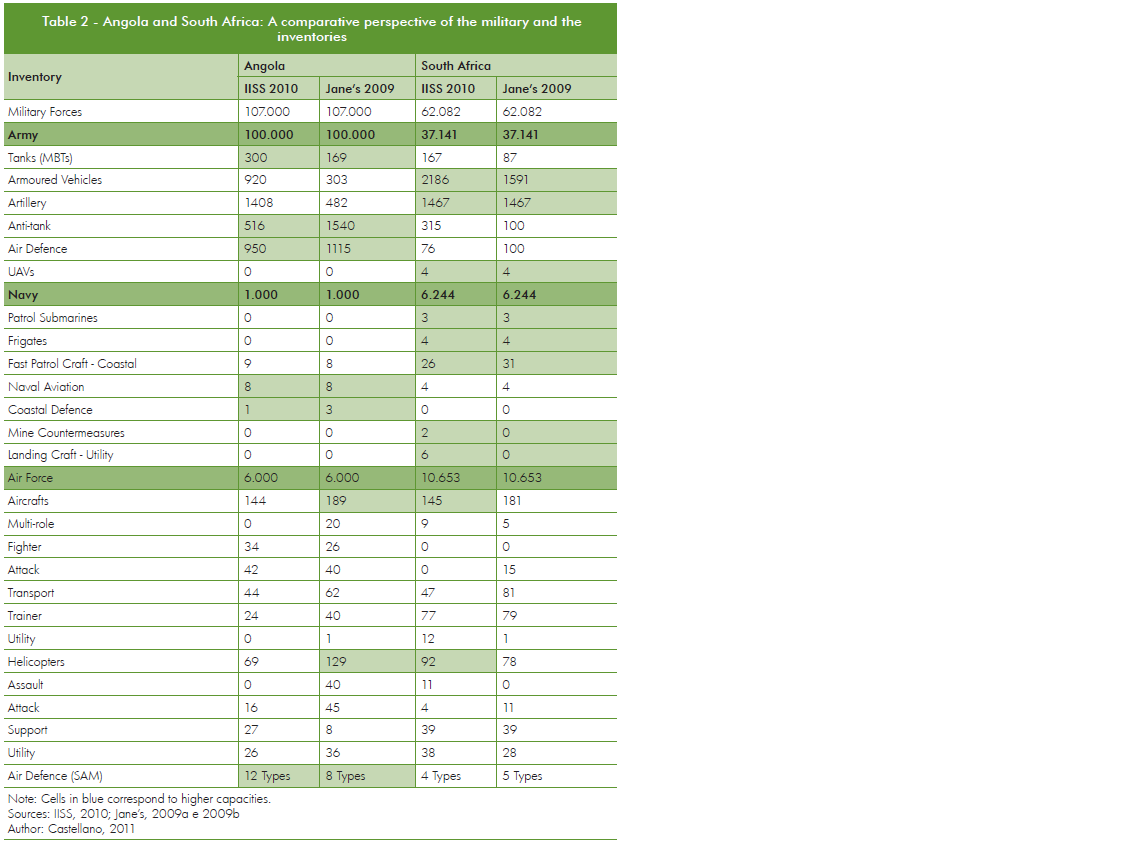

Table 2 – Angola and South Africa: A comparative perspective of the military and the inventories

display a current photograph of the military inventories of their armed forces (quantitative analysis). Based on the databases of the IISS and Jane’s the table on below shows the simplified equipment configuration of the two countries.

South Africa has superior numerical superiority in regard to the naval forces. This superiority also exists in a quality grade, considering that the country, unlike Angola, has submarines and frigates (as discussed below), while Angola has to be content with only a reasonable anti-ship defence system with patrol aircraft (operated by the Air Force) and missile defence on the ground. However, the capabilities of both countries seem more equivalent in the case of air and ground forces. In the Air Force, although South Africa has modern multirole aircraft, Angola has a diverse set of relatively modern aircraft for air combat and attack, and holds between 8 and 14 Suk hoi Su-27 Flanker fighter jets, with capacity and range comparable to the South African JAS39D African Gripe. On the one hand, both fighters have similar missile and simple weapons capabilities (weapons of approximately 30 mm and hard points for a maximum of six missiles). On the other hand, the Angolan fighter is faster (2,500 km/h against 2,204 km/h), has greater flight range (3,530km against 3,200km), higher service ceiling (18,500m against 15,240m) and higher maximum load (30,450kg against 14,000 kg). In the army, although older, the T-72 Angolan MBTs can cope with the South African Olifant Mk1A in conventional combat. Despite the weakness of his turret armour, the T-72 weapons are greater than the Olifant’s (125mm against 105mm) and can reach similar speeds (approximately 60km/h).

However, any quantitative analysis is incomplete without a more qualitative assessment of capabilities which in this case, involves an understanding of the modernisation process of the armed forces.

In Angola, in spite of past cooperation with most countries in the region, the recent threats of internal guerrilla groups operating on its soil and abroad (usually backed by rival neighbour regimes) continue to favour the legitimacy of high spending on the defence, of robust armed forces and of an equipment profile which includes capabilities for regular warfare. Thus, ‘Angola retains sufficient hardware and troops to make it a regional military power in sub- Saharan Africa. Massive conscription expanded the overstretched Angolan Armed Forces to give it a quantitative, if not qualitative, edge over any other military in the region’ During the war against UNITA, Angola developed one of the most powerful militaries on the continent. By 2002, her forces were established in the territory of three of its four neighbours (DRC, Congo and Namibia), with occasional struggles on the border of Zambia.

Regarding the modernisation of forces, it is noteworthy that the FAA was trained by Portugal assessors in the 1990s and by South African and North American private military companies since 1993. One can also cite a military training agreement signed with Russia in 2000, encompassing technical support for the operation of newly purchased equipment from countries of the former USSR. It should be noted that after 1999, rising oil prices enabled a process of relative modernisation of the FAA, especially in the Army and the Air Force, in a period that also encompassed the final phase of the fighting against UNITA. The arsenal from Eastern Europe helped centrally in the successes against insurgents in the 2000s. Between 1998 and 2000 Angola purchased stocks of the Warsaw Pact, among them 320 MBTs (Main Battle Tanks), 160 AIFVs (Armoured Infantry Fighting Vehicles), more than 100 artillery pieces, 46 multi-rocket launchers, some attack planes Sukhoi Su-22 Fitter (reinforcing the existing inventory of these planes) and some attack helicopters Mi-24 Hind. Obtaining qualitative benefits was also embraced by the acquisition of some units of more modern equipment, such as the Sukhoi Su-27 Flanker. Other weapons, parts and advisers were agreed with Russia in 1999.

The exception to the modernisation program was the Navy, which had already lost all its combat and patrol ability and half of its staff in the year 1990, due to the focus in the war against UNITA, which never developed maritime presence. In 2002 it was reported that the Angolan Navy did not have reliable ships and vectors, which opened room for occasional South African presence. More recently, in 2004, an initial cooperation with the Namibian Navy allowed the establishment of coastal fishing patrols by utilising the neighbouring country vessels. Moreover, the development of the oil sector has pushed the government to reconsider the construction of a coastal defence force. Currently, the Navy uses the Air Force’s air-to-air vectors and does not utilise several bases along the coast.

The FAA has undergone training through a contract with a private US company, Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), and with the International Military Education and Training (IMET). US aid came primarily to the Navy, due to greater concern with oil exports from its third largest trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa and the second largest destination for US investment in Africa, after South Africa. In September 2005, there was also the Med-Flag 2005, a naval exercise involving 700 Angolan and 200 American troops.

The army’s modernisation process, which received large amounts of relatively modern equipment since the late 1990s [43], also encompassed training programs established by South African private companies (especially Executive Outcomes). Links with China were also established in 2007 an agreement on military-technical cooperation was signed, which will be implemented in the form of supplies of military equipment, to be delivered. Currently, senior officers of the two countries have a program of experiences exchange.

Regarding the Air Force, it had been trained in the 1990s by Executive Outcomes (1993-1996), the American Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI) and Portuguese teams of instructors.

Until the 1990s the Angolan military doctrine mixed aspects of Portuguese military thinking with Soviet, Cuban and Warsaw Pact schools. In the mid-1990s the resumption of the war by UNITA caused a subtle change in this framework. The external advisors of Executive Outcomes enabled a refinement of the Soviet era style, by creating new and reduced Operational Manoeuvre Groups. These are battalions with reduced formation and conventional capability, but much faster and more flexible. As a result, the units have become smaller and more agile, making it difficult for UNITA to face conventional combat in the resumption of war in 1998. The new line enabled combined formations of artillery, motorised and mechanised infantry and armoured cavalry. This reality has led the insurgents to be defeated as a conventional threat in 2000, pressing them to modify the standard of combat to guerrilla tactics.

Thus, it is noteworthy that, although the formation has been specialising in the mobility profile, the conventional strategy remained present in the FAA and visible in the size of the army and the profile of recent acquisitions (MBTs).

Finally, the largest on going reform of the Angolan armed forces is the structuring of a more concrete national army of conscripts. This has been done by four current priorities, (i) increasing the professionalism of the armed forces, especially in the army, (ii) increasing the combat readiness of soldiers, (iii) increasing the organisation, control and registration of staff and equipment (iv) increasing the imposition of discipline, and (iv) improving the living conditions of soldiers and increasing the rate of literacy among the military.

Concerning South Africa, it is important to remember that the country has the best equipped and trained military in sub-Saharan Africa, with significant operational experience. The country also has a Military Industrial Complex under construction with the presence of companies such as Denel (aerospace equipment), Advanced Technologies and Engineering (avionics and weapons systems), Grintek (avionics and traffic control), and Reutech (tactical communications equipment, mine detector and electronic fuses). The political importance of these strategic industries could be seen when, in 2006, the government saved Denel from financial losses that could result in bankruptcy, depositing almost R2 billion in the parastatal organisation.

Despite these advances, it should be noted that post-Apartheid, the SANDF has undergone unfavourable changes, both internally and externally. Internally, it had to distance itself from the internal coercive role attributed to apartheid security forces. Externally, there was a need to build forces that did not alarm its neighbours, still traumatised by the history of the SADF’s destabilising role in the region. As a result, a force of regional vocation was built, but centrally based on the legitimacy exercised by peacekeeping mandates. This profile was supported by a portentous process of modernisation of the armed forces in the 2000s.

Following successive reductions in military spending in the 1990s, which ultimately affected the operational readiness of the forces and reduced the number of military bases, South Africa has gone through an extensive process of equipment modernisation throughout the 2000s. The 12 year long purchase program, the 1999 Strategic Armaments Package (SAP), totalled more than US$ 6 billion and was directed almost exclusively at marine and aeronautics.

Among the navy’s equipment, priority was given to (i) the control of maritime Exclusive Economic Zone against illegal fishing and piracy, (ii) the carrying out of support tasks to maritime peacekeeping missions and (iii) the patrol of oil regions on the continent’s Atlantic coast. The main equipment purchased were four frigates class MEKO A-200 and three diesel-electric submarines (both bought from Germany), as well as four Lynx helicopters to equip the frigates. In the Air Force the purchase list was composed of 26 Gripen JAS39D and C, 24 Hawk trainer aircraft and 30 utility helicopters Agusta Westland A109UH.[44]

The modernisation also involved the increment of vectors. Embarked missiles (spear) Umkhonto were established in the new MEKO frigates, new models of self-propelled artillery Denel/GDLS 105mm were presented. In order to establish elements of rapidly deployable air-transported artillery and the establishment of a joint program with Brazil for the development of the agile short-range air-to-air missile (AAM) A-Darter, whose prototype is being produced by Denel. Thus, the SANDF has confirmed its standing as the most modern armed forces in the continent.

However, two main issues put pressure on the profile and the regional role assumed by the SANDF, which has established peacekeeping and reconstruction tasks in Burundi, Ivory Coast, DRC, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Nepal and Sudan, and supported electoral processes in Comoros, DRC, Madagascar and Lesotho in recent years, totalling almost 4,000 military abroad. The first issue was the option to modernise the armed forces throughout the decade, which caused between 30 per cent to 40 per cent of the budget to be directed exclusively to the military purchases program, leaving few resources for training and operations spending. The second factors were the national economic difficulties that emerged, at the same time, pressures on defence spending to remain below 2 per cent of the GDP, and the negative effects of deterioration of resources committed to defence due to inflation and currency devaluation. This reality favoured the reproduction of incertitude about the viability of the regionalised profile of South African forces. Some experts spoke of the need for increased spending by 30 per cent in 2011 so that the SANDF could support its regionalised force profile. The armed forces’ modernisation program also generated additional costs with training and integration of new structures and systems. If not prescribed in a DoD rubric, it may end up draining the resources dedicated to the establishment of regional operations.

Moreover, in spite of the prodigious modernisation program in South Africa, throughout the 2000s, the army was marginalised in relation to the Air Force and the Navy under the purchase program. As a result, the army is currently too small to sustain its current missions and there is a lack of resources for training, maintenance and purchase of vital equipment. Positive signs were given in 2007 with the publication of a plan to increase the army’s budget in the Defence Update. Seeking to generate greater flexibility and mobility in the army, which is the backbone of peace efforts in the continent, the government established a new structure for the organisation[45] and committed to prioritise purchases for this force[46].

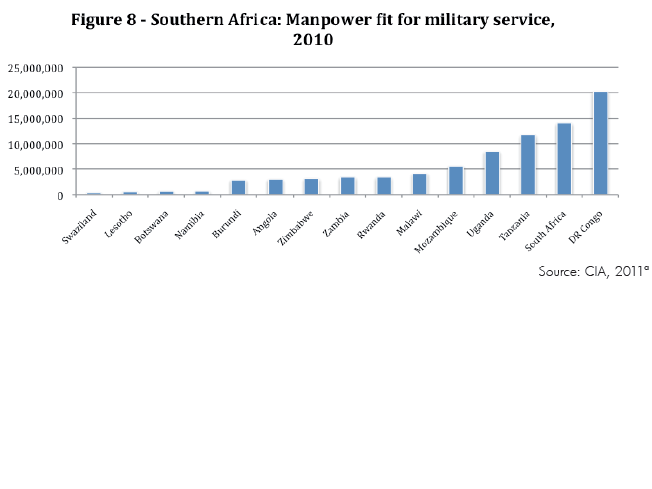

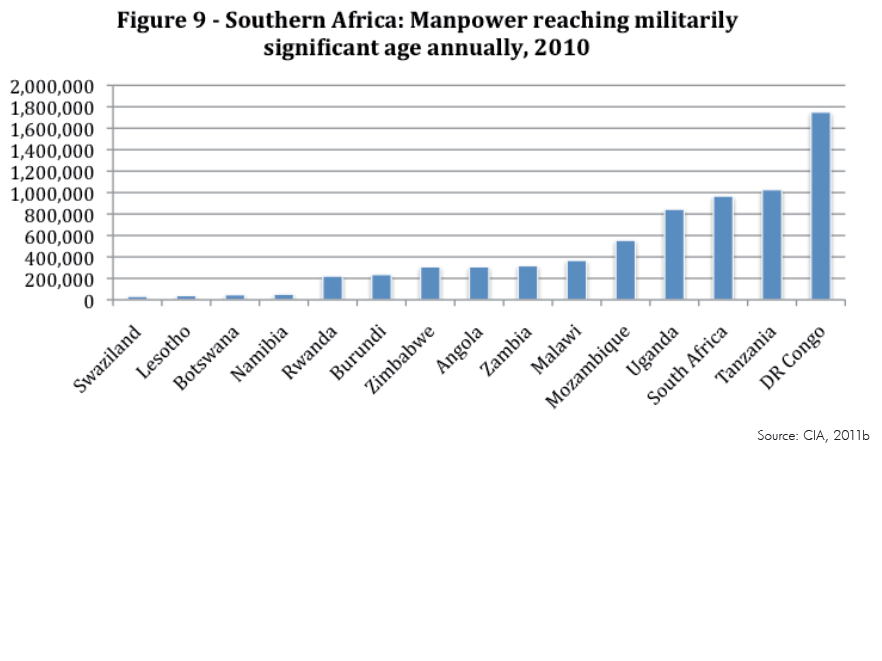

Another problem present in the SANDF is staff shortages in terms of quantity and quality. This became aggravated by the post-apartheid policy of racial quotas, creating a shortage of qualified officers to meet the requirement of a reduced white contingent. Moreover, there seems to be little identification between the army and the population, which causes difficulties in the recruitment of volunteers. The number of people able to take on military tasks and are reaching military age in South Africa would suggest the opposite (see Figures 8 and 9), but currently, the SAAF has just 38 per cent of the required number of fighter pilots, 60 per cent of technicians, 72 per cent of helicopter pilots, and 68 per cent of transport pilots.

The end of conscription and compulsory military service is another source of this problem. The system was replaced by a force of volunteers. It is important to note that the DoD sought to cut the size of the armed forces in order to reduce operational expenses since the early 1990s. Thus the paradox of having an ambition to sustain a force for regional stability and a policy of budget cuts and staff was apparently resolved by a doctrine which assumes that their actions will only occur if preceded by peace agreements. This implies that their role in combat is reduced to the extent that in peace operations (even in missions of peace enforcement) the activities of the armed forces are considerably reduced compared to conventional military operations, specifically with regard to attrition and friction. An example of this is that within the largest UN peacekeeping mission, MONUSCO, with a mandate clearly under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, the actions of the peace force are of surgical character and of material and logistical support to heavier military operations by the FARDC.

Therefore, despite the extensive modernisation of forces during the 2000s and its declared regional vocation, the SANDF seems to face practical problems in sustaining South Africa as a single pole in Southern Africa. It can be concluded with the analysis of the material capabilities of the Southern Africa countries, especially the two major players, that Angola is an emerging local power to the regional power, or is already a regional power exercising an unbalanced polarity in relation to South Africa.

Shared vulnerabilities

Despite the preponderance of these countries as poles of the Southern Africa region, it is necessary to highlight some shared vulnerabilities. The first refers to demographic issues, the second, to problems concerning the concept of security adopted by each country.

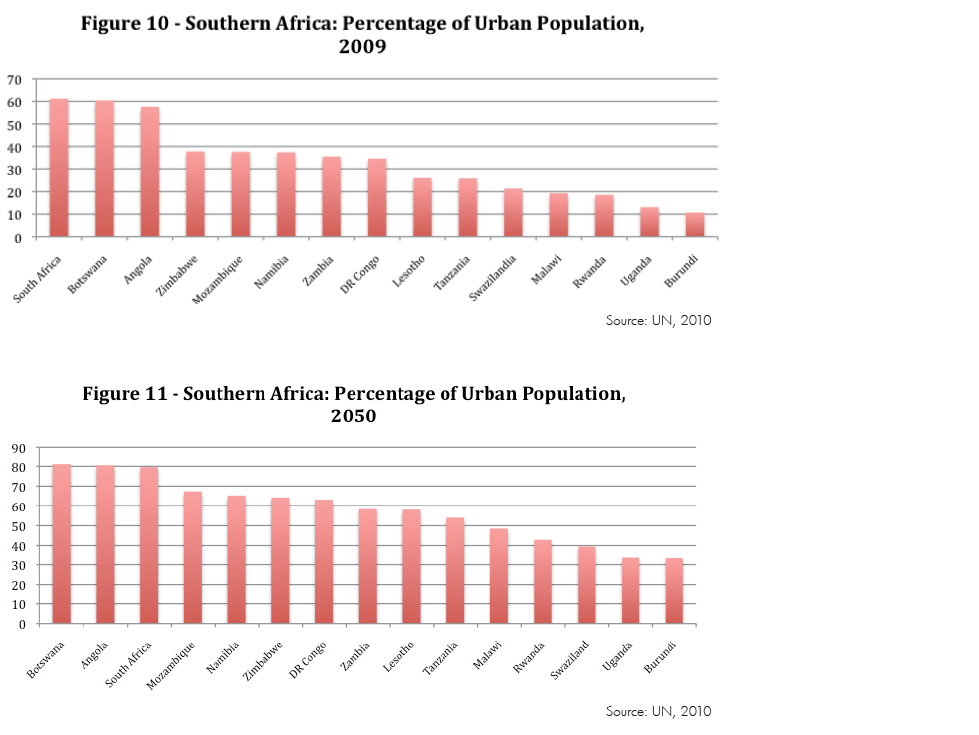

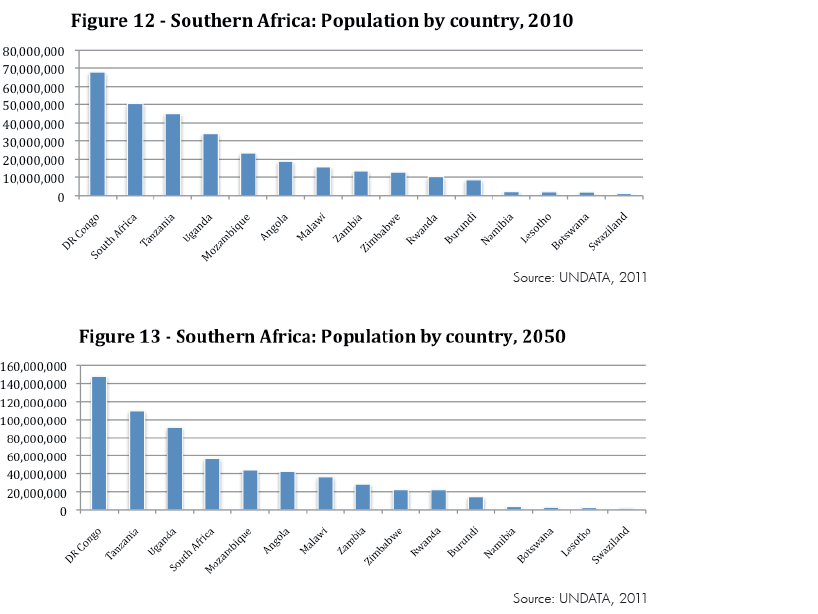

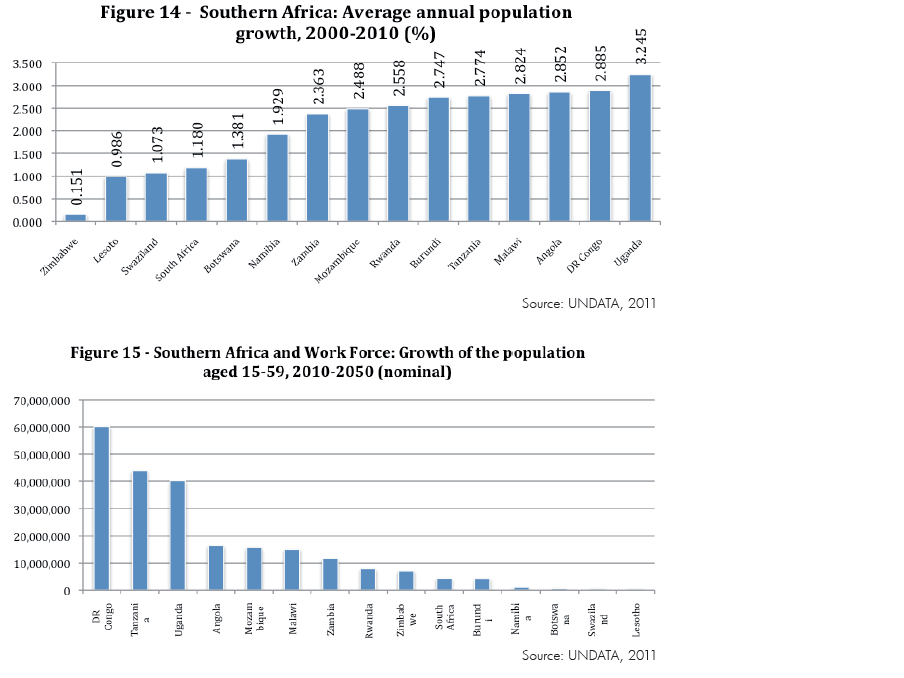

In the context of population issues, although both countries currently hold a large percentage of urban population, and this view remains to the year 2050 (see Figures 10 and 11), the scenario does not seem so favourable regarding their absolute population compared with other countries in the region (see Figures 12 and 13). It is estimated that Angola will continue in 2050 as only the seventh country in the region in terms of absolute population. In relation to South Africa, it is assumed that the country will move from second to the fourth place in terms of population size, suggesting the loss of some relative power on the continent. The situation seems to be a direct result of the low rate of population growth that South Africa presents to the larger countries in the region (see Figure 14). Data of particular concern, especially for South Africa, refers to the growth prospects of its workforce by the year 2050 (see Figure 15).

This demographic framework may have implications for the capacity of countries to sustain their economic development, their military capacity and therefore their position in the region. What can also be learned from the various figures is that, in case there is a positive response to the stabilisation of conflicts in the Great Lakes region and an appropriate reform of its security forces, the DRC may become a new hub in the region. Its population growth and especially its workforce can generate positive results for the country’s position in the region. It should be noted that since the splitting of Sudan in early 2011, the DRC is the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa in territorial terms.

In the context of the adopted concept of security, neither Angola nor South Africa appear to have a sense of security that is able to effectively gather the region under its leadership due to a variety of reasons. In the case of Angola, it is because of its excessive focus on internal security. In the case of South Africa, it is related to the concept of human security.

Angola’s security concept is based on national security. This concept stems from its historical experience with the civil war, when the greatest threat to the state was within its borders. In adopting this concept, Angola seeks to prevent the formation of new forces’ claims of power and rivalry to the state and to consolidate the process of state-building. However, the external result of this conceptual approach is that Angola only interferes in the region when security issues could disrupt its own internal security. Its participation in the wars in the DRC and Congo-Brazzaville and its alliance with Namibia to suppress UNITA are indicators that seem to support this perception. Even more recently, Angolan support to the training of security forces of the DRC seems to be due to the fact that the security of its neighbour directly affects its national security. This is evident when one sees that Angola does not think twice about expelling Congolese citizens from the country.

The exception to this rule can be perceived also in the case of the DRC when, in 2006, Angola once again demonstrated that the government of dos Santos would assist Kabila in the case of an invasion by Rwanda, even where the threat of UNITA had been demobilised.

However, even with attitudes based on concerns about national security, Angola ended up acting at times as an actor in stabilising the region, seeking to block the war of aggression and assistance from central government against insurgent groups. Thus, history suggests that this model, even if focused on domestic concerns, can stabilise the region unintentionally. On the other hand, its focus on national security, sometimes translated into non-interventionism, can block the development of more regular and incisive regional policies. In the case of Côte d’Ivoire in 2011, the objection to an AU intervention facilitated space for French action, showing how this self-centred security perception may be harmful in avoiding extra-regional interventions in the continent.[47]

In the case of South Africa, human security and non-interventionism, except those supported by mandates of international organisations, are the basis of the adopted security concept. The construction of this security posture was directly related to the construction of new armed forces in postapartheid and sought different political interests, such as (i) a basis for legitimacy in society, (ii) to find elements that could assimilate the different factions integrated into the armed forces, (iii) to avoid topics that could bring conflict to its own forces and (iv) to establish an ethical role which could assimilate the different factions within the armed forces with the society. The result of this policy was the refusal to defend territorial integrity and condemn the war of aggression in the two wars of interstate character in the region (First and Second Congo Wars), which created 3.8 million deaths in total. This resulted in a division within SADC and checked the posture of the organisation as a force to intervene in armed conflicts in the region. [48]

In short, there is a paradox between the fact that South Africa has the continent’s strongest military and the fact that it does not interfere in heavy combat and conflicts centrally related to regional stability. Its military capacity could be translated into the blockade of wars of aggression, in a regional alternative to extra-regional interventions, and in military aid tasks in counter-insurgency operations against destabilising transnational and national groups within the continent. Today the tasks are restricted, especially, to peacekeeping missions and aid to the reform of security forces after peace accords. In this case it implies that power-sharing agreements (as the one produced, with South African mediation, in the DRC and Burundi and defended by the country in case of Angola) are more desirable than those supported by a military definition on the battlefield (such as the one in Angola).

The above table summarises the findings of this section regarding the polarity of the Southern Africa RSC during the 2000s. During the decade, the economic primacy of South Africa was constantly being followed by Angola, which has always stood out among the other countries in the region. With regard to military factors, the capacity of both countries became a little less asymmetric. Angola has the largest military and recent experience with regular and irregular war. South Africa has a better balance between the forces, which are structured for a more advanced stage of modernization. Finally, the graph also suggests future demographic problems and the possibility of the rising of the DRC as a regional power, which will be conditioned by its ability to solve the current internal conflicts.

Conclusion

This article tried to make a contribution to Buzan and Waever’s attempt to apply the Regional Security Complex’s model to Southern Africa. More specifically, it sought to analyse the security dynamics, to limit the boundaries and to assess the polarity of the RSC during the 2000s. This task was accomplished in three stages.

The first outlined the peculiarities that involve the application of the RSC model to the African case. Moreover, it pointed out the main analytical flaws committed by the authors in adapting their model to Southern Africa. Among them, we can mention the classification of the Great Lake of Central Africa as an RSC by itself, separated from Southern Africa; and the perception that the Southern Africa RSC is characterized by unipolarity, exercised by South Africa. The following sections sought to present an alternative interpretation of these points, using the study of the security dynamics present in the 2000s, mostly not included in the work of the authors.

The second section described these dynamics, divided into domestic and regional levels and intended to review the Southern Africa RSC’s boundaries. We concluded that Buzan and Weaver seemed to be right to include DR Congo into the Southern Africa RSC, but wrong to detach it from the security dynamics of the Great Lakes region. For the period after the author’s book, three hypotheses were evaluated and we concluded that DR Congo is still integrated both to Southern Africa and Great Lakes RSCs. As the model doesn’t permit overlapping RSCs, we concluded that Buzan and Waever’s Southern Africa and Great Lakes RSCs are integrated into the same RSC, here called the Southern Africa RSC. This is due mainly to the position and the security dynamics within the DR Congo. In short, our argument is based on three main realities (i) the impossibility to detach the DRC (the whole country) from the security dynamics of the region; (ii) the interconnection between the region’s security dynamics and characteristics of the Second Congo War, which was a typically regionalized conflict; and (iii) the necessary connection between the conflicts in the region after 2003 and the policy of South Africa and Angola as regional powers –

The third and most important section assessed the type of polarity in the Southern Africa RSC, based on indicators of material capability with data for the 2000s. With the analysis of indicators such as GDP, GDP per capita, GDP growth, size of the armed forces, military expenditure and military expenditure to GDP, it became apparent that although South Africa is the country with the largest economic capabilities of region, Angola stands out among the other countries, especially for its economic and military capabilities. Consequentially, little doubt remains that during the last decade Angola has become at least partially a regional power (in terms of material capability). Additional studies are necessary to assess the behavioural aspects of its power. This could expand the finding to a full measurement according to the author’s concept, which embraces both material capability and behaviour.

A brief assessment of the military capabilities of the two regional powers was then presented in order to identify the specific characteristics of polarity. From this exercise it was noted that the South African National Defence Forces (SANDF) are more modern and have maritime capabilities superior to the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA). However, these latter forces have relevant land and air capabilities, aided by their extensive experience in regular and irregular wars, guaranteeing the material basis for Angola’s position as a regional power. The data supports, therefore, the interpretation that there is an unbalanced bipolarity in Southern Africa in favour of South Africa, but qualifies Angola as a power distinct from the rest of the region. Even with this reality, vulnerabilities presented by both countries suggest that this position is not guaranteed. Future demographic problems and the adoption of inadequate security concepts seem to act as variables which may affect the stability of the power of both countries.

For future work we also suggest the development of studies to assess (i) the existence of a sub-Saharan Africa RSC, which could contain, it is assumed, three sub-complexes (of West Africa, the Horn of Africa and Southern Africa); (ii) the security relations between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa (Maghreb) seeking to verify if these regions are part of different or same RSC; and (iii) what are the power poles of a possible African Regional Security Complex.

Read the full paper external pageherecall_made.

[39] ‘During the Cold War (when most of the theoretical apparatus of International Relations was constructed), the existence of bipolarity made this seem easy to do. There was a big gap between the superpowers and the rest, and their rivalry was openly global in scale’ (Buzan and Waever 2003:30).

[40] The process was marked by atomization. This is because the focus has been accomplished without the construction of a permanent national army with unified training and which could contribute to the social formation of the soldiers, as has been the case in Angola. This was, partially, a result of the lack of coordination between bilateral partners in the case of training of integrated forces and the large number of partnerships without an integrated programme and focused on shortterm (Boshoff 2008, Wolters and Boshoff 2006, Jane’s, 2009c). It should also be noted that initial option for the process of mixage (former rebels are placed with other troops, but their units are not dissolved, only juxtaposed) over the brassage one (they are individually mixed and redistributed geographically) resulted in difficulties in establishing hierarchy and command and control over integrated forces, mainly over the ones that kept parallel command structures. There was also insufficient funding and misuse of scarce resources (ICG 2006). This was a main result of the lack of coordination between international donors, largely due to disputes over leadership of the process (Boshoff et al, 2010) and important international constraints that block multilateral resources directed to restructuring the military (ICG, 2006). As a final result there was a distrust of the rebel groups about the whole process.

[41] The Angolan economy was directly favoured by the end of civil war and the rising oil prices with the proximity of the Iraq War (the sector accounts for 50 per cent of GDP). Some authors claim that the country can overcome in the near future the oil production of Algeria, Libya and Nigeria, tripling its production and becoming the largest oil producer in Africa (Jane’s 2009:7). The mining of diamonds also bring some comfort to the Angolan economy, especially after the approval of the Kimberley Process certification scheme. However, oil and diamonds were the only sectors of the economy that actually worked after the war. Fishing, coffee production and the industry collapsed with the armed conflict. The country’s infrastructure was also destroyed by the war, which gives central importance to its partnership with China. Currently, huge investments are needed to reopen access to the interior and clear landmines (Jane’s 2009a: 7). There is still dependence on food imports and a deficit in revenue of 36 per cent if oil is excluded from the calculation (IISS 2004:343).

[42] South Africa has the most developed economy in Africa and is characterised as the dominant power economically, diplomatically and strategically in the environment of Southern Africa (Jane’s 2009b: 4). It represents a third of the product of sub-Saharan Africa, much of its military spending and a major source of foreign direct investment in the continent. The South African economy was also particularly hard hit by the economic crisis of 2008, the consequence of capital outflows and the resulting drop in revenue and the deterioration of the budget, which is undermined by accumulated inflation from previous years, which reached 10 per cent in 2010. During the 2000s, the economy gained new impetus with the increase in employment, appreciation of government bonds and the consequent increase of national reserves. However, good results were carefully considered. The government has chosen to establish fiscal prudence and has sought budget surplus, which resulted in significant effects relating to restraint in military spending.

[43] It should be noted that in spite of the modernisation process, the equipment purchased do not represent new generations of equipment and in some cases serve only to be a source of spare parts.

[44] The air force had also ordered in 2006 eight Airbus A400M cargo to replace its fleet of C-130 that was coming to an end of service life. The project would have benefited the national armaments industry, especially companies like Denel and Aerosud, which would participate in the production of the aircrafts’ embarked electronics and avionics, generating an income of at least $ 400 million for the companies. However, in November 2009 the government abandoned the project and the planned purchases because of escalating costs and significant delays in the delivery of the products (IISS 2010:291). One can also suggest that the problem is related to the fact that the government had established that the funds for this purchase would come from additional funding. However, the Treasury has adopted a tough stance insisting that the funds should come from the defence budget, which proved the increasing pressures on training, maintenance and other purchases (IISS, 2007:259).

[45] From 2008 there has been a structural change in the army, after the publication of the document ‘Vision 2020’ in 2006. A new divisional structure has been established: ‘introduction of administrative staff structures similar to the G1 sections seen in many other armed forces. This is due to be Followed by the establishment of land, training and support commands, along with ten brigade head-quarters, and one mechanised and one motorised division headquarters. South Africa’s Special Forces Brigade will to continue to operate under the authority of the chief of joint operations and the president’(IISS 2008:277).

[46] In terms of purchases it may be cited the Hoefyster Project (contract of 264 IFVs to replace the Ratel), Project Vistula (purchase of more than 1,300 tactical logistic vehicles, 733 of 8 wheels and 579 of 6 wheels), the Project Sapula (new family of APCs to replace the 30 years old Casspir and Mamba), a system for ground-based air-defence (GBADS), involving multiple batteries of SAMs Starstreak. However, these projects seem to be subject to the country’s economic performance in 2011, except in the case of the Project Hoefyster won by Denel, for the production of a new generation of IFVs with 5 variants based on the Finnish vehicle Patria (IISS 2008:277).

[47] It is very important to Angola to self-perceive as an actor of regional responsibilities. Its current experience with the reconstruction of the army after years of civil war and the focus on building a cohesive national army of conscripts could serve as a model for countries in the region experiencing post-civil war instabilities (DRC, Burundi, and Rwanda).

[48] As an exception it may be cited the 1998 intervention in Lesotho, a country vital to the internal security of South Africa.

REGULAR.jpg)