Lessons of the Refugee Crisis: What Europe can expect from Germany´s Changing Migration Policy

28 Nov 2016

By Fabrizio Tassinari and Sebastian Tetzlaff for Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageDanish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)call_made on 22 November 2016.

While the refugee crisis has exposed the severe limitations of EU decision-making, German choices have had a knock-on effect on the rest of Europe. The politicization of German migration policy will likely force Angela Merkel to take a step towards more conservative positions ahead of the 2017 federal election. This will again require the EU to adjust to Berlin’s policy turns.

Recommendations

■ The practice of ‘bandwagoning’ on Germany is to be welcomed as a short-term solution if it serves as an entry point for a more systematic and fairer EU approach.

■ The first place to watch for Berlin’s commitment to a European solution to the refugee crisis is its support for EU ‘migration compacts’ with five African countries and the fledgling European Border and Coastguard.

■ In the run-up to the federal election in 2017, European partners can expect the governing parties in Germany to retune their rhetoric in order to confront the populist challenge.

In September 2016, Angela Merkel declared that, if she could, she would turn back the clock so as to prepare the German administration for the challenges of the 2015 refugee crisis. However genuine her statement was, it does not add up. Over the past eighteen months, the German government has performed not a U-turn on migration and refugee policy so much as what effectively amounts to a pirouette, returning to positions more akin to the status quo ante the refugee crisis.

In the half-decade preceding the crisis, which coincided with what was then known as the ‘Arab Spring’, German policy decoupled the problems with mass migration facing southern European Union members from those linked to the domestic integration of migrants. Some prominent voices, from a former Board member of the German Bundesbank, Thilo Sazzarin, to Minister of the Interior Hans Peter Friedrich, criticized the multicultural logic and practical limitations of Germany’s domestic integration policies.

However, the population generally supported the government’s handling of immigration on the grounds that it largely kept Germany at arm’s length from the massive flows being experienced by frontier states such as Italy and Greece. In a statement reflecting Berlin’s close adherence to the Dublin regulation, stipulating that asylums-seekers should only apply for asylum in the first EU country they enter, Chancellor Angela Merkel stated as late as 2013: ‘I’d like to remind you that we have quite a large number of asylum-seekers that we have accepted [in Germany] by European comparisons. We need to add some short-term measures on Lampedusa [but] we have today not made any qualitative change to our refugee policy.’

What changed drastically in the summer of 2015 was that Germany coupled the external pressure building up at Europe’s borders, especially along the so-called Balkan route, to its domestic response. Merkel’s statement ‘Wir schaffen das’ (‘We’ll manage’) became the symbol of this strategic turn, as 1.1 million asylum-seekers, a third of them from Syria, flowed en masse into Germany without proper registration in the countries they had passed through earlier. But what was arguably a laudable decision from a humanitarian standpoint quickly turned into a gargantuan logistical challenge and was increasingly framed in the public discourse as a security concern. Hence the gradual adjustment of the past twelve months, which has taken German policy back to its earlier and more familiar, more pragmatic basis, but which has also fundamentally changed the landscape in which Europe is managing the migration crisis.

‘Bandwagoning’ and consequences for European and German politics

Chancellor Merkel has made no secret of the fact that a lasting solution to the refugee crisis will have to be a European solution. The way in which this has translated in practice is a penchant for expediency on the part of Germany, on which other European countries and EU institutions have more or less willingly ‘bandwagoned’.

The epitome of this change is the EU–Turkey refugee deal, spearheaded personally by Merkel on a controversial visit to Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in October 2015, and then negotiated by her in March 2016, when it was then endorsed by the rest of the EU. The resulting ‘one-for-one’ swap between ‘irregular’ asylum-seekers who have crossed the Aegean from Turkey to Greece and those already residing in Turkey has been heavily criticized by human rights groups and independent observers on humanitarian grounds. But from a purely diplomatic and power-political standpoint, what emerges out of it is a modus operandi in which accepted European consensus-building mechanisms and normatively grounded positions are sidetracked for the sake of expediency.

This adjustment is mirrored in the domestic realm in Germany. The EU–Turkey deal has paid political dividends in so far as it has provided the centerpiece of the German government’s response to the crisis. However, this did not prevent a domestic backlash, with right-wing segments of the political spectrum profiting from the perceived lack of organization and depicting Merkel’s management style as reckless. The far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has become an established party in ten German states, and if current polling trends continue, it will also be represented in the national parliament after the Federal Elections of 2017.

Similarly, conservatives such as Horst Seehofer, Chairman of the CSU, the Bavarian sister party of Merkel’s own Christian Democratic Party, repeatedly pressured the Chancellor to cap the number of refugees to be allowed into the country. After a year of intensifying politicization of the migration debate, the European Union and discussion about migration, integration and Islam all revolve around questions of domestic security. The ultimate shift was reinforced by terror attacks in France, Belgium and Germany, some of which were carried out by refugees who had entered Europe in the course of the refugee crisis. Opponents to the government’s handling of the crisis linked the dramatic decrease in arrivals since March 2016 to the effective closure of the Balkan route rather than being attributed to effective crisis management. As a result, populists continue to profit from the crisis, as testified by the impressive AfD gains and severe CDU losses in local elections in Berlin and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

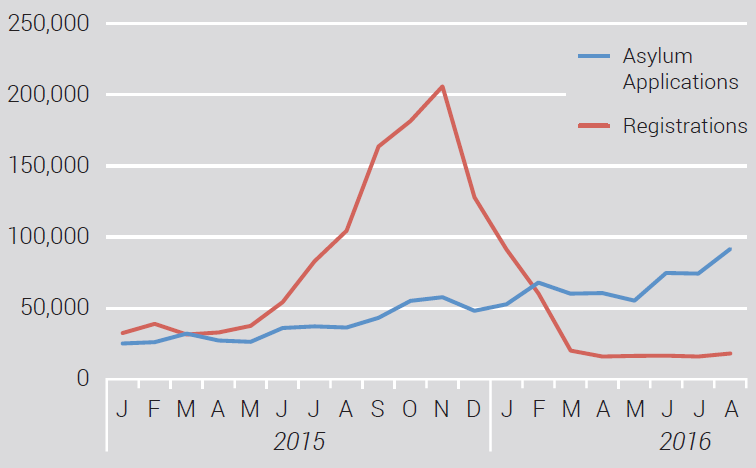

EASY-System Registrations and Asylum Applications

Mainstreaming the crisis

The refugee crisis has altered the modus operandi of EU policy-making on matters of both internal and external security. In the run-up to the crisis, some member states acted with little prior consultation and then presented their partners and EU institutions with a fait accompli, leaving them with just the ability to rubber-stamp decisions. This has created a so-called ‘domino effect’ of chain reactions, of consequence to a country like Denmark, as Germany’s northern neighbour. With the Schengen system and Dublin convention effectively overcome by events, the domino effect is not only physical but also metaphysical, as it changes standards of acceptable European behavior. This search for expediency and even unilateralism can only become an antidote to European paralysis if it ultimately proves capable of channeling national interests and resources into viable, collective European solutions.

In this respect, the evidence of the past eighteen months challenges Chancellor Merkel’s claim that the solution to the refugee crisis is a European solution. The proposed quota system that is supposed to share out the burden of refugees among all EU member states has floundered amidst a ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ attitude championed by Central European states. The more tangible effects of the Europeanization of the refugee crisis occurred when member states ‘bandwagoned’ on Germany, as in the case of the EU-Turkey deal. Such trends can only be welcomed if expediency in the short term gives way to a fairly shared, systematic and durable organization of security for the EU external border in the longer term. German support for European initiatives such as the so-called ‘migration compacts’ with African countries and the fledging European Border and Coastguard – an upgraded Frontex – would make up for many of the real or perceived European failures in this area recently.

Ahead of the federal election in the fall of 2017, European partners must also expect a gradual mainstreaming of immigration-critical positions on the part of the German government. Having started by acknowledging criticism of the CSU, Chancellor Merkel now appears intent on targeting the segments of the population that have grown disaffected with her leadership and turned to the populist anti-immigrant AfD. Success in striking a discursive middle ground, whereby urgency is defused while depriving the populist right of some of its signature arguments, may represent the most genuine political challenge facing Chancellor Merkel and, if successful, also prove to be the most enduring legacy of her management of the refugee crisis.

About the Authors

Fabrizio Tassinari is a research coordinator and a senior researcher at DIIS. Sebastian Tetzlaff is a research assistant at the Institut für Europäische Politik.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.