Arctic Rivalries: Friendly Competition or Dangerous Conflict?

23 Oct 2017

By Mikkel Runge Olesen for Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageDanish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)call_made on 3 October 2017.

Introduction1

Global warming is gradually changing the rules in the Arctic. After centuries at the margins of global politics, the region was briefly propelled into global politics during the Second World War and during the Cold War, due to supply routes across the Atlantic and due to underwater sea-lanes and flight patterns across the Arctic region for nuclear armed vessels2 – only to drift to the margins again when the Cold War confrontation ended. Now, once again, the region is attracting outside attention. This time, however, global interest in the Arctic is far more multifaceted. Thus, the region’s claim to importance rests not only on geo-strategic military factors (though also that), but increasingly also on its potential in terms of extraction of natural resources and increased international trade. Processes that are further complicated by on-going sovereignty disputes over both Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and Extended Continental Shelves as well as over the judicial status of the Northeast and the Northwest Passages.

As the region gains in importance, questions arise about how the different arctic actors will pursue their interests in the Arctic. Will cooperation and friendly competition be the order of the day, or will disagreements lead to conflict? This question has gained increasing relevance as the Ukraine crisis spilled over into the Arctic in 2014 with the launching of Western sanctions against Russian oil and gas extraction from the Arctic seabed. This article seeks to address this question by assessing the conflicting and congenial stakes and interests of the most important Arctic states across two types of issues: Direct security issues, often determined by out-of-region dynamics, and more Arctic-specific issues connected with the sovereignty disputes and the possible rush for Arctic resources.

Security Issues

At the military strategic level, the only possible dyad for conflict is between Russia and the West. Thus, with the exception of Russia, all littoral states are NATO allies creating a natural “lid” for how serious problems between the Western Arctic states are likely to get. The same applies to the EU. Even China, the most powerful non-arctic state to take an interest in the region, simply does not have the necessary presence in the Arctic for conflicts to escalate to the military level. So how likely is serious conflict in the Arctic between Russia and the West? Let us now consider the security interests of Russia and the Arctic NATO members in turn.

Russia

No other state in the Arctic can match Russia in terms of territory or Arctic capabilities. Thus, Russia’s Arctic shoreline amounts to roughly half the way around the Arctic Ocean, and its fleet of nuclear icebreakers grants Russia unrivaled access to the region. However, Russia is also the most vulnerable of the Arctic powers. First of all, among the Arctic Five (Russia, the US, Canada, Denmark and Norway) – the group of states with a coastline to the Arctic Ocean – only Russia is not a NATO member, leaving it isolated in any dispute with the NATO countries. Secondly, Russia keeps much of its strategic deterrence in the Arctic, especially at the Kola Peninsular3. From a Russian perspective, that also makes the Kola Peninsular a potential target for NATO should conflict ever arise4. Finally, and perhaps of most immediate importance, Russia is economically vulnerable in the Arctic because of the role of Arctic offshore oil and gas extraction in the Russian energy strategy. Not much activity takes place offshore today, but this is where Russia plans to go once its land based oil and gas fields run dry. The challenge, however, is that Russia is in dire need for Western investments, technology and know-how to get such project going5. Investments, technology and know-how that Western sanctions over Ukraine currently block – sanctions chosen by the West, like most sanctions, because of Russian vulnerability in this regard6.

This combination of military and economic vulnerability has generally led Russia to pursue a dual strategy in the Arctic. On the one hand, old Soviet military bases in the Arctic are being reopened7 and the number of Russian military exercises in the Arctic has increased. This likely serves to show the West that Russia is prepared to protect its interests in the Arctic. Incidentally, such policies are also great for domestic consumption, by playing into a narrative of Russia as a great power in the north8. On the other hand, however, the general trends of Russian Arctic diplomacy have been quite conciliatory towards its neighbors. Russia was an integral part of the Ilulisat declaration of 2008 under which the five Arctic coastal states confirmed their commitment to peaceful conflict resolution in the Arctic9. And Russia has generally shown itself willing to play by the rules in the Arctic when it comes to, for example, negotiations over extended continental shelf. Thus, with the exception of certain colorful Russian stunts, such as the semi-official planting of the Russian flag at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean in 200710 or the confrontational trip to Svalbard by Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin in 201511, Russia has generally pursued a relatively restrained diplomatic approach to the Arctic. This has been the case both before and the onset of the Ukraine crisis. This is largely due to the fact that Russia, perhaps more than any other Arctic state, has much to gain from Arctic cooperation and much too loose from conflict in this particular region. This may eventually change, if the sanctions prove semi-permanent, but the continuity that Russia has displayed in its Arctic policies so far, shows the degree of resilience of the approach.

The Arctic NATO countries

While the US nuclear submarines have never left the Arctic, and while the US turned its attention to National missile defense in the Arctic already in the early 2000s, by utilizing and upgrading its existing bases in Alaska and Greenland, the US was for many years regarded as a the sleeping giant of the Arctic region. This has to do with US perception of the Arctic in general. Thus, aside from the role of the Arctic in US strategic deterrence, the US has long not prioritized the Arctic very much. It partly has to do with domestic politics. The US, for example, is, alone amongst the coastal states, has yet to ratify UNCLOS, the most important legal framework for the Arctic. Thus, in spite of support from both Republican and Democrat presidents the ratification has as of yet failed to get through Congress12. This presents an obstacle for effectively delimitating the last contested sovereignty claims in the Arctic where the US has a claim (see below). Furthermore, it was not until 2011 that the US began to participate at the level of Secretary of State in the biannual Arctic Council ministerial meetings. Finally, US Arctic hesitance has also been reflected in procurement for the US Coastguard, which has only recently been able to gain traction for its wishes for new icebreakers (the US currently only has two functioning icebreakers – the aging heavy icebreaker the Polar Star and the newer medium class icebreaker Healy)13. Thus, when it comes to icebreakers, a key Arctic capability, the US is lagging far behind Russia.

This lack of US priority given to the Arctic region has also led the US to try to refrain from provoking Russia in the Arctic. It has therefore been US policy not to seek to engage NATO in the Arctic. Naturally, the sanctions on Russian oil and gas extraction represents an exception to this approach, but these sanctions should be regarded purely as spill-over from other regions. The sanctions are a consequence of the Ukraine crisis and Russian Arctic interests only chosen because they are vulnerable to such sanctions. It therefore says little of Western or US Arctic strategy.

Canada, the middle power of the Arctic, has so far been in line with the US on general security strategies in the Arctic. Thus, though Canadian rhetoric about Russia in the Arctic has varied wildly in recent years – from perhaps the most hawkish among all the Western Arctic states under Stephen Harper14 to a much more conciliatory tone under Justin Trudeau15. However, Canada has consistently opposed NATO involvement in the Arctic under both Prime Ministers. This has to do with both a Canadian wish to avoid relations with the Russians from deteriorate too much16 while also, according to a leaked behind closed doors remark by Harper, to keep out nations trying to gain influence “where they don’t belong”17.

Of the smaller Arctic NATO members, the Kingdom of Denmark has thus far supported the line of limiting NATO’s involvement in the Arctic for the time being. Thus, while it’s the clear Danish position that NATO’s article five, naturally, also applies to the Arctic, the Kingdom sees little reason for increased NATO activity in the Arctic at this point18. This also matches the general Danish foreign policy strategy of seeking to preserve a peaceful Arctic through engagement with Russia, in spite of foreign policy differences in other regions19. At the same time, however, the Kingdom also makes sure to demonstrate itself a useful and loyal ally to the US in the Arctic. Thus, Greenland is home to the Thule Airbase, which plays an important role in the US National missile defense. This secures a certain amount of goodwill in the US (though arguably not as much as during the Cold War20). The base has also, however, been a recurring topic of controversy between Denmark, Greenland and the US. The latest of these, over how a Greenlandic firm recently lost an important contract to provide services to the US airbase to a US competitor, even though legal safeguards in the original US-Danish base treaty of 1951 should safeguard such contracts for Danish and Greenlandic firms only. The issue is currently unresolved and for the last couple of years Denmark has been trying to use its great relationship with Washington to try to solve the contract controversy and similar issues before they turn domestically toxic within the Kingdom (with varying degrees of success)21.

Finally, Norway, the other small littoral Arctic NATO country, has thus far been the most vocal proponent for more NATO involvement in the Arctic22. To understand that state of affairs, one has to consider that for Norway the Arctic region is really two different regions. As an Arctic Ocean littoral state Norway has been an active member of both the Arctic Five and the Arctic Eight (the Arctic Council) in dealing with issues of the circumpolar north. However, when it comes to Norwegian security in the Arctic, one must especially consider the dynamics at play in the south of the Arctic region, in the so-called Northern Area, which covers continental Northern Norway, Svalbard and the Barents Sea. Here Norway, critically, shares both a sea- and a land-border with Russia. On this basis, the Norwegian Arctic strategy has traditionally been one of strategic duality towards Russia. On the one hand, Norway has been at the forefront of diplomatic efforts to keep Russia within the bounds of Arctic institutions. The greatest mark of success of these efforts is undoubtable the fact that Norway managed to reach an agreement with Russia in 2010 on a division of the last contested areas of the Barents Sea23. On the other, Norway has also always played an important role in NATO’s military deterrence of Russia in the Northern Area. Thus, ever since the days of the Cold War Norway has served as an important observation post of Russian military movements in the heavily militarized Murmalsk Oblast. Add to this that Norway itself has signaled its intention to meet increased Russia military build-up in the Arctic with a strengthening of the Norwegian armed forces in the Arctic as well24.

Arctic exceptionalism? The innate security dynamic of the Arctic Region

As we can see, the chief security issues in the Arctic are actually not that much about the Arctic at all. As was the case during the Cold War, the greatest danger to Arctic stability remains conflict imported into the Arctic region from elsewhere on the globe. Indeed, the Arctic itself may have a dampening effect on conflict. Thus, the region is far from an ideal battlefield. According to a 2009 interview with Canada's, then, chief of defense staff, General Walter Natynczyk: "If someone were to invade the Canadian Arctic, my first task would be to rescue them"25. On the flip side, cooperation on communal tasks like search and rescue, preventing oil spills and scientific endeavors is rewarded more in the Arctic than in less inhospitable regions. Indeed, the benefits of cooperation in facing these challenges has enabled the Arctic Countries in reaching binding agreements on how to meet those challenges26. Furthermore, with a few exceptions, the general cooperative attitude between the Arctic countries has largely continued even after the Ukraine Crisis27. Many key regional dynamics of the region thus counteract, to an extent, the spill-over conflict potential of the outside world.

Sovereignty Issues, Economics Stakes and Outsider Interests in the Arctic

Though military conflict may be unlikely, the Arctic is still home to many unresolved disputes and divergent interests. Here, we will look at the sovereignty issues primarily between the Arctic Five as well as their economic interests in the Arctic before moving on to consider the Arctic interests of outsider countries.

Territorial disputes

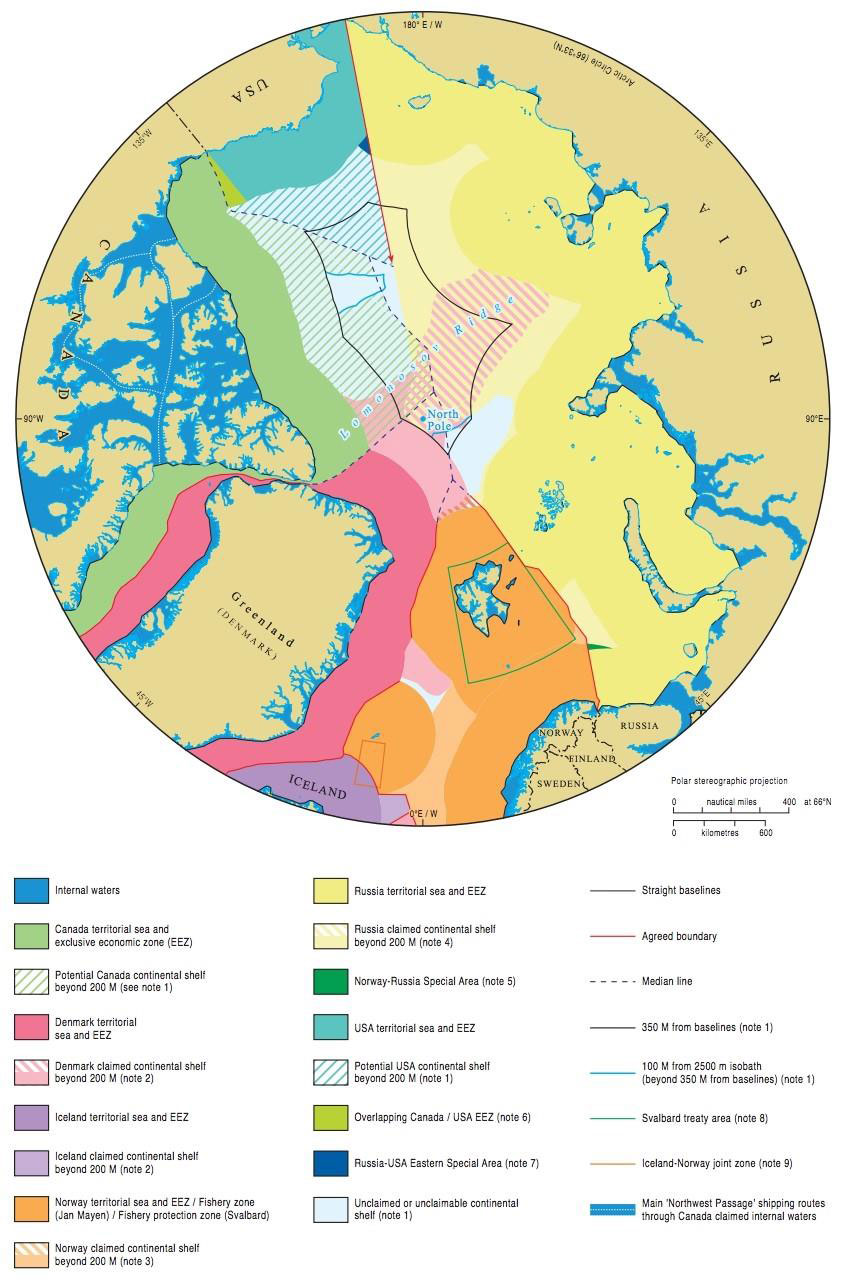

Central among these are the disputes over exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and extended continental shelf. According to UNCLOS (UN Convention on Law of the Sea), each country has the right to 200 nautical miles of EEZ beyond their territorial seas, and the right to apply for extended continental shelf even further beyond that. According to the rules provided in UNCLOS, each country can lay claim to extended continental shelf only to the extent that they can prove that their continental shelves extend beyond the 200 miles EEZ28.

As of 2017, the process of delimitating the Arctic Ocean is still ongoing. The US and Canada remain in disagreement regarding EEZ boundaries the Beaufort Sea29. This dispute is made all the more difficult by prospects for hydrocarbon resources. The presence of such resources is both a complication and a possible incentive for solution, however, as few companies will invest in oil or gas extraction while the judicial status of the region is in doubt. Thus, this dynamic likely played a role in the successful solution of the, similar, Russian-Norwegian dispute in the Barents Sea in 201030.

Moving on to extended continental shelf claims, several issues remain unsettled. Thus, all Arctic littoral states with the exception of the US, which has yet to ratify UNCLOS, has submitted claims to extended continental shelf and/or are in the process of doing so. As can be gathered from the map (see below), the largest remaining disputes, in terms of direct overlap, involve Russia, Canada and the Kingdom of Denmark (through Greenland). All three have agreed, however, to follow the rules laid down in UNCLOS meaning that each has agreed to submit scientific evidence for their claims to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). Denmark submitted its latest claim in 2014 and Russia in 2016, while Canada submitted a partial claim in 2013 and is expected to follow up that claim in 201831. Overlapping claims, however, can be found to be equally scientifically valid, and in that case it will be up to the involved nations to reach a peaceful solution.

Finally, the Hans Island dispute bears mention as the only dispute in the Arctic over land territory. The small 1,3 km2 sized island has been claimed by both Denmark and Canada, and the island has been an object of controversy for years. As the rights to the surrounding sea territory has mostly been settled, however, the island is little more than an irritant for the relationship between the two countries32.

Common for the Arctic Five however, is the resistance against attempts by outsiders to interfere with their division of the Arctic. Thus, a chief motivation behind the Ilulisat Declaration of 2008 was also to unite the Arctic Five against outside influence. This includes, for example, the EU Parliament, which has at times called for Arctic Treaty preserving the Arctic Ocean as common heritage for mankind33. By agreeing to exclusive rights to disagree about contested areas, the five thereby do have considerable common ground from which to negotiate.

Figure 1 Map of the existing maritime disputes in the Arctic. Source: Durham University

The Northeast and the Northwest Passage disputes

As the Arctic is warming up so too prospects are rising for the use of the Northeast and the Northwest Passages as alternative routes for international trade. Furthest along in development the Northeast Passage holds the intriguing possibility of shortening many trade routes between Europe and East Asia considerably34. It is also the center of considerable controversy, however, with Russia insisting on treating the route as internal waters while other actors, most notably the US and the EU, insist on treating the passage as an international waterway. In this regard, it is worth noting that China, a key stakeholder in any development in world trade that might facilitate better connections between Asia and Europe, has, at least for the time being, shown itself willing to accept Moscow’s sovereign rights over the Northeast Passage35.

Similarly, the legal status of the Northwest Passage is contested as well. Here Canada lays claim to the passage as internal waters, while the US is most active proponent of the international waterways principle. This, ironically, puts Canada in a position very similar to that of the Russian position on the Northeast Passage.

For the time being, however, both conflicts have been approached in a low-toned manner signaling little interest on the US or the EU side to avoid immediate confrontation36. Furthermore, the immediate economic potential should not be overstated. For shipping companies the distance between key harbors is only one factor among many when calculating the overall cost of a transit route. Both the Northeast and the Northwest Passages remain closed for much of the year and are still hampered by unreliable seasons and the transits remain risky without icebreaker assistance37.

Economic stakes in the Arctic and what it means for Arctic stability

But how serious are these disputes really? Intrinsically connected with the sovereignty issues are the prospects for extraction of valuable resources from the Arctic. A key point here is that such prospects are much greater in the uncontested areas of the Arctic, than they are in the contested areas. This provides an important incentive for all the Arctic Coastal states to cooperate since the extraction of resources from the uncontested areas, estimated to hold around 80% of the Arctic region’s resource wealth38, require political stability in order to attract interest from the extractive industries. This is, as mentioned, especially true for Russia, which has an intrinsic interest in getting Western sanctions in this area lifted as soon as possible.

Outside powers, notably especially the EU and China also have a role to play in this respect. Several EU member states are members of the Arctic Council (Denmark, Sweden and Finland) or Arctic Council observers, and the Kingdom of Denmark is a littoral Arctic state, though Greenland itself left the EU in 1985 over fishing disputes and is now labelled under “Overseas Countries and Territories of the EU”. The EU has itself sought observer status in Arctic Council, but its application was deferred in 2013 due to differences with, not least, Canada over the EU’s seal ban.

This happened again in 2015 and 2017, though this time the reason was the EU’s conflict with Russia over the Ukraine39. While the practical consequences have been limited, the EU can participate in the work in the Arctic Council as an observer until the decision is made40, the seal controversy in particular underlines the general dilemma of the EU in the Arctic: How to balancing a strong stand on environmental protection of the Arctic against concerns for the region’s economic development41.

For China it is especially the resource potential of the Arctic region that has attracted its attention. In fact, at the moment, China currently seems more interested in resource extraction than exploiting the new sea routes42. Chinese interests includes oil and gas, where China has sought an increasingly close relationship with Russia43, but also minerals such as iron ore or rare earth metals (REE). China’s REE interest in Greenland, in particular, has caused some concern in the West as China is already the supplier of more than 90% of world demands in REE. However, such concerns should be tempered by the fact that that monopoly rests on China keeping down the prices to make it commercially unviable to extract REE’s elsewhere in the world44.

Resource extraction in the Arctic is costly, however. For this reason, however, most schemes for the exploitation of Arctic resources are currently being dampened by the low world prices on natural resources, and most industries will need to see a spike in raw materials prices to make the Arctic truly interesting. That should give the stakeholders of the Arctic region some time to find solutions to their disputes.

Conclusion

So what are the current prospects for conflict in the Arctic? In military terms, it is, at present, very unlikely and the greatest sources of instability come from spill-over from outside the region rather than regional dynamics. No country has a greater interest in a stable Arctic than Russia, and while Russian economic vulnerability in the Arctic has made it a target for Western Ukraine-Crisis-related sanctions, cooperation in the Arctic region has thus far proved relatively resistant to such disruption. Neither a possible rush for Arctic resources, nor the outstanding sovereignty issues are likely to change that in the foreseeable future – not least since most of the possible resource wealth of the Arctic is likely to be located in uncontested areas. The economic development of the Arctic requires stability and many areas of governance in the Arctic provides great incentive for cooperation between the Arctic states. Rather than conflict, we are therefore much more likely to see cooperation mixed with competition in the Arctic. Many unresolved issues remain especially with regards sovereignty disputes. Traditionally, such disputes can take a long time to resolve. The Arctic region is unlikely to be any different. In time, however, common interests will likely lead to their resolution.

Notes

1 This article was previously published, in French, in Politique étrangère https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/politique-etrangere/arctique-une-exploration-strategique#sthash.779p46wD.dpbs. The author is grateful for the permission to release the English version of the article as a DIIS Working Paper. The research for this article is supported by the Independent Research Fund Denmark grant-ID: DFF – 1329-00039.

2 Young 1992: p. 179-213 (Young, Oran R. Arctic politics: Conflict and cooperation in the circumpolar north. Dartmouth College Press, 1992.)

3 Klimenko 2016: p. 26-28. (Klimenko, E., 2016. Russia’s Arctic security policy. Still quiet in the High North? Stockholm: SIPRI (SIPRI Policy Paper No. 45)).

4 Konyshev & Sergunin 2014: p. 82-83. (Konyshev, Valery, and Alexander Sergunin. "Russian Military Strategies in the High North." Security and Sovereignty in the North Atlantic. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2014. 80-99.)

5 Keil 2013: p. 180 (Keil, Kathrin. "The Arctic-A new region of conflict? The case of oil and gas." Cooperation and Conflict, Published online before print June 6, 2013, 162-190).

6 Rahbek-Clemmensen 2017: p. 3. (Rahbek-Clemmensen, J. (2017). The Ukraine crisis moves north. Is Arctic conflict spill-over driven by material interests? Polar Record, 53(1), 1-15.)

7 Klimenko 2016: p. 26-28.

8 Roberts 2015: p. 122. (Roberts, Kari (2015): ”Why Russia will play by the rules in the Arctic”, Canadian

Foreign Policy Journal, pp. 1-17, DOI: 10.1080/11926422.2014.939204).

9 http://www.oceanlaw.org/downloads/arctic/Ilulissat_Declaration.pdf (accessed May 27 2017).

10 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/aug/02/russia.arctic (accessed May 27 2017).

11 http://barentsobserver.com/en/politics/2015/04/russias-sanctioned-rogozin-landed-svalbard-18-04 (accessed May 27 2017).

12 Wright, Thomas. "Outlaw of the Sea." Foreign Affairs (August 7 2012). https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/oceans/2012-08-07/outlaw-sea

13 http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/feb/19/coast-guard-icebreakers-in-arctic-vital-to-us-acce/ (accessed May 27 2017).

14 Plouffe, Joël (2014) “Stephen Harper’s Arctic Paradox”, Canadian Global Affairs Institute, https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/cdfai/pages/448/attachments/original/1418790337/Stephen_Harpers_Arctic_Paradox.pdf?1418790337 (accessed May 15 2017).

15 Sharp, Greg (2016) “Trudeau and Canada’s Arctic Priorities: More of the same” The Arctic Institute, http://www.thearcticinstitute.org/trudeau-canadas-arctic-priorities/ (accessed May 15 2017).

16 Åtland 2014: p. 158. (Åtland, Kristian. "Interstate relations in the Arctic: an emerging security dilemma?." Comparative Strategy 33.2 (2014): 145-166).

17 http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/canada-under-increasing-pressure-to-come-up-with-co-ordinated-nato-response-to-russia-in-arctic (accessed May 27 2017).

18 Forsvarsministeriet (2016): p. 18. Forsvarsministeriet (2016): ”Forsvarsministeriet fremtidige opgaveløsning i Arktis. BILAG 2: Sikkerhedspolitisk redegørelse om udviklingen i Arktis af 25. februar 2016” http://www.fmn.dk/nyheder/Documents/arktis-analyse/bilag2-Sikkerhedspolitisk-redegoerelse-om-udviklingen-i-arktis.pdf (accessed May 29 2017).

19 https://www.b.dk/globalt/samuelsen-advarer-mod-konflikt-og-konfrontation-i-arktis (accessed May 27 2017).

20 Rahbek-Clemmensen, Jon, and Anders Henriksen. "Grønlandskortet: Arktis' Betydning for Danmarks Indflydelse i USA." CMS Report, University of Copenhagen (2017).

21 Olesen forthcoming. (Olesen, Mikkel Runge (forthcoming), »Lightning rod: The US, Greenlandic and Danish relations in the shadow of post-colonial reputations« in Kristensen, Kristian Søby & Jon Rahbek-Clemmensen (red.) Greenland and the International Politics of a Changing Arctic – Postcolonial Paradiplomacy between High and Low Politics. Routledge.)

22 Grønning, Ragnhild (2016), “NATO reluctant to engage in the Arctic”, highnorthnews http://www.highnorthnews.com/nato-reluctant-to-engage-in-the-arctic/ (accessed May 15 2017).

23 Moe, Fjærtoft and Øverland 2011: 151-152. (Moe, Arild, Daniel Fjærtoft, and Indra Øverland. "Space and timing: why was the Barents Sea delimitation dispute resolved in 2010?" Polar Geography 34.3 (2011): 145-162).

24 Norge 2017: p. 20. (Norge: ”Nordområdestrategi - mellom geopolitikk og samfunnsutvikling”, 2017) https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/fad46f0404e14b2a9b551ca7359c1000/nord_strategi_2017_ny.pdf (accessed May 15 2017).

25 http://www.smh.com.au/breaking-news-world/arctic-threats-and-challenges-from-climate-change-20091206-kcx6.html (accessed May 27 2017).

26 http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/our-work/agreements (accessed May 28 2017).

27 Heininen, Lassi. "Security of the Global Arctic in Transformation—Potential for Changes in Problem Definition." Future Security of the Global Arctic: State Policy, Economic Security and Climate. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016. 12-34.

28 Olesen 2015 (Olesen, Mikkel Runge ” Common and Competing Interests”, in: Jokela, J. (ed.) Arctic Security Matters. Ch. 4, EU Institute for Security Studies (2015)

29 Sharp, Greg (2016) “An old problem, a new opportunity: A case for solving the Beaufort Sea boundary dispute “where they don’t belong,”” The Arctic Institute, http://www.thearcticinstitute.org/an-old-problem-a-new-opportunity-a-case-for-solving-the-beaufort-sea-boundary-dispute/ (accessed May 27 2017).

30 Moe, Fjærtoft and Øverland 2011: 151-152.

31 http://www.rcinet.ca/en/2016/05/03/canada-to-submit-its-arctic-continental-shelf-claim-in-2018/ (accessed May 28 2017).

32 Byers 2013: p. 14-15. (Byers, Michael. International law and the Arctic. Vol. 103. Cambridge University Press, 2013.)

33 EU 2008, “European Parliament resolution of 9 October 2008 on Arctic governance” http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P6-TA-2008-0474+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN&language=EN (accessed May 29 2017)

34 Guy & Lasserre 2016. (Guy, Emmanuel and Frédéric Lasserre “Commercial shipping in the Arctic: new perspectives, challenges and regulations”, Polar Record, Volume 52, Issue 3 May 2016, pp. 294-304.)

35 Huang, Lasserre & Alexeeva 2015: p. 38. (Huang, Lasserre & Alexeeva 2015b: p. 39. Lasserre, Frédéric, Linyan Huang, and Olga V. Alexeeva. "China's strategy in the Arctic: threatening or opportunistic?." Polar Record (2015): 1-12.)

36 Guy & Lasserre 2016.

37 Guy & Lasserre 2016.

38 Buchanan, Elizabeth. “Arctic Thaw: Arctic Cooperation and Russian Rapprochement”, Foreign Affairs, (2016)

39 Haines, Lily: “EU bid to become Arctic Council observer deferred again” Barents Observer May 4 2015 http://barentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2015/05/eu-bid-become-arctic-council-observer-deferred-again-04-05 (accessed May 12 2017); http://www.highnorthnews.com/norways-foreign-minister-warns-against-arctic-resource-race/ (accessed May 27 2017).

40 https://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about-us/arctic-council/observers (accessed May 27 2017).

41 Pelaudeix and Rodon 2013: p. 75-76. (Pelaudeix, Cecile, and Thierry Rodon. "The European Union Arctic Policy and National Interests of France and Germany: Internal and External Policy Coherence at Stake?." Northern Review 37 (2014)).

42 Huang, Lasserre & Alexeeva 2015: p. 39.

43 Huang, Lasserre & Alexeeva 2015: p. 37-38

44 http://www.mining-technology.com/features/featurethe-false-monopoly-china-and-the-rare-earths-trade-4646712/ (accessed May 12 2017)

About the Author

Mikkel Runge Olesen is a senior researcher for the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.