Intelligence Models in Practice: The Case of the Cuban Missile Crisis

16 Jan 2015

By William Wilson for Canadian Military Journal (CMJ)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made in Vol. 15, No. 1 (Winter 2015) of the external pageCanadian Military Journalcall_made, which is published by the National Defense and Canadian Armed Forces.

Introduction[1]

The overall complexity of the intelligence profession poses serious conceptual challenges for practitioners and scholars alike. For one, the exact nature of the relationship between policymakers, analysts, and collectors can be difficult to articulate. Moreover, the highly interactive order of decisions, actions, and events cannot be easily captured in ‘linear’ descriptions. At any given time, decisions, actions, and events can take place simultaneously, or even in reverse logical order. Finally, the secretive nature of intelligence work presents the greatest challenge of all: sometimes it is just not known or ‘knowable’ as to what has actually occurred.

In light of these challenges, a number of intelligence models have been created to help grasp this complexity. None of the models claims to completely or faithfully represent the intelligence profession, acknowledging the inherent difficulty of mapping a highly fluid and oftentimes ambiguous work process, but they all claim a degree of authenticity and promise certain advantages to those who employ them. These advantages often relate to greater insight into (and presumably, control over) the intelligence process itself. Among the different models on offer, three prominent ones include the cyclical model, the target-centric model, and the multi-layered model, as presented in the first section of this article. Each model is based upon a slightly different understanding of the intelligence process, and each carries different strengths and weaknesses as a result.

The remainder of this article aims to test the usefulness of these three models by evaluating them against the Cuban Missile Crisis. This crisis demonstrates many of the conceptual challenges confronting intelligence practitioners and scholars, making it an ideal test case. Bearing this in mind, the second section outlines the unique characteristics of each model, while, the third section provides a brief and general history of the Cuban Missile Crisis. In turn, the fourth section situates the three intelligence models within this history to critically evaluate their respective merits. The final section serves as a short conclusion, restating the article’s main findings, and returning to the overall complexity of the intelligence profession. In the end, the best model is the one that acknowledges this complexity and seeks to incorporate it.

Intelligence Models in Theory

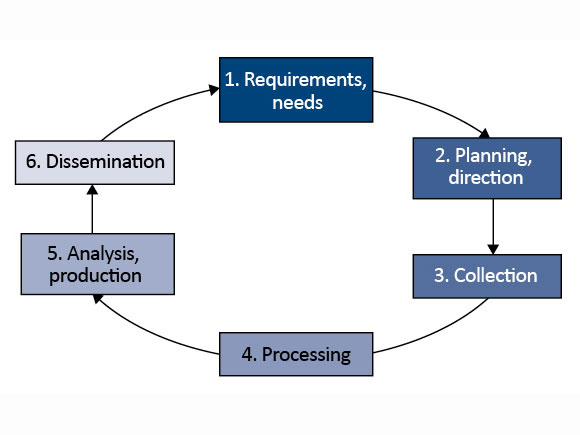

As mentioned, the intelligence profession is very complex, involving multiple actors and roles. Some of the most critical actors involved in the intelligence process include policymakers, analysts, and collectors. The different roles performed by these actors generally reflect their different namesakes. In this respect, policymakers set the overall objectives of the intelligence process and guide its workflows. They are also the primary consumers of intelligence products.[2] Collectors are responsible for the collection of raw data, which is then interpreted by analysts, culminating in an intelligence ‘product’ destined for consumption by policymakers. Individual intelligence operations can vary in length and scope, but they tend to follow this basic pattern of interaction among policymakers, analysts, and collectors.[3] Admittedly, such a pattern is not ideal, failing to properly account for the inherently unequal statuses between these three types of actors, and overstating the autonomy of each actor within the overall intelligence process. Nonetheless, any intellectual exercise that seeks to impose clear meanings on highly fluid and oftentimes ambiguous workflows is likely to face these problems. This basic description of the intelligence profession—commonly known as the “cyclical model”—is represented in Figure 1.1. It is the model that practitioners and scholars often encounter first when attempting to ‘map’ the intelligence process.[4]

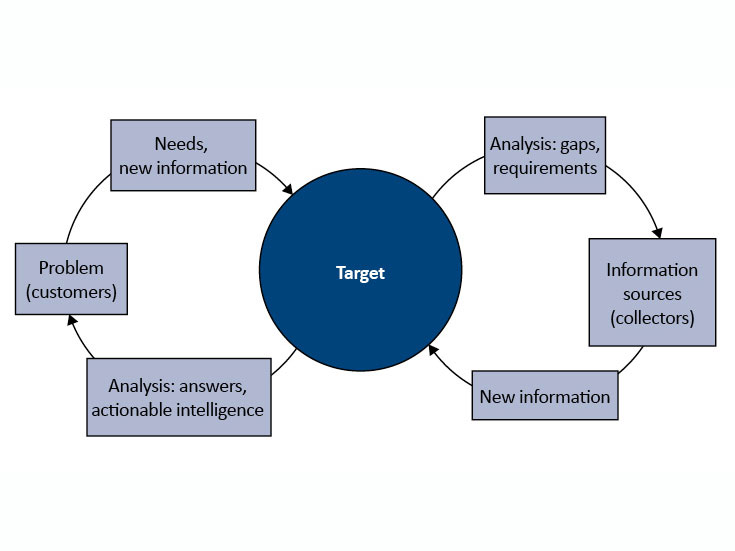

In contrast, Robert M. Clark has developed the “target-centric” model, which aims to address some of the perceived faults of the cyclical model. The target-centric model is depicted in Figure 1.2. Overall, this model attempts to increase the degree of interaction among policymakers, analysts and collectors, acknowledging the complexity of their true relationship. It also attempts to avoid an overly ‘linear’ presentation of the intelligence process, permitting forward and backward movements across the work cycle. Finally, it attempts to situate the intelligence objective at the centre of the intelligence process, pushing other considerations to the periphery. As Clark argues:

The target-centric approach has more promise for complex problems and issues than the traditional cycle view. Though depicted as a cycle, the traditional process is in practice linear and sequential, whereas the target-centric approach is collaborative by design. Its nonlinear analytic process allows for participation by all stakeholders, so real insights into a problem can come from any knowledgeable source. Involving customers increases the likelihood that the resulting intelligence will be used. It also reminds the customers of (or introduces them to) the value of an analytical approach to complex problems.[5]

These are only some of the purported strengths of the target-centric model, but they speak directly to the perceived faults of the cyclical model. Ultimately, it is Clark’s view that the target-centric model creates greater appreciation for the intelligence process as a whole, including the distinct contributions of policymakers, analysts, and collectors. This point can be seen in its unorthodox appearance when compared to the traditional cyclical model.

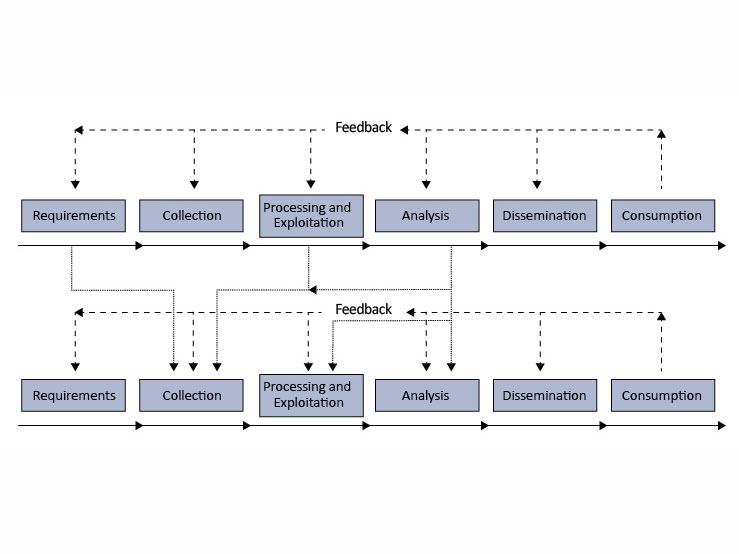

A third intelligence model has been introduced by Mark M. Lowenthal, namely the “multi-layered model.” Like the target-centric model, this model aims to address some of the perceived failings of the cyclical model. Having said this, as shown in Figure 1.3, it does not radically depart from the basic structure of the cyclical model. Instead, it attempts to make provision for greater discretion and contingency within the intelligence process, noting decisions, actions and events can move in almost any direction, while maintaining the same basic conceptual categories and workflows as the other two models. Lowenthal is aware of the overall complexity of his model, but presents this feature as its key strength: “This [model] is a bit more complex, and it gives a much better sense of how the intelligence process operates in reality, being linear, circular, and open-ended all at the same time.”[6] As a set, the three intelligence models discussed in this section claim to offer practitioners and scholars alike greater insight into (and presumably control over) the intelligence process. Their applicability to real-world intelligence situations, however, is debatable, as exemplified by the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

What follows is a short history of the Cuban Missile Crisis. This history is based mainly upon the writings of Raymond L. Garthoff, who worked in the US Department of State as a special assistant for Soviet bloc affairs during the Crisis.[7] The history also draws upon the writings of several other authors to provide greater perspective.[8] It is hoped that the Cuban Missile Crisis, which contains distinct intelligence ‘successes’ and ‘failures,’ will serve as an illustrative, real-world example by which to test the three intelligence models under discussion. In particular, the Cuban Missile Crisis demonstrates the importance of hierarchy within the intelligence process; the non-linear and non-sequential nature of intelligence work; and the importance of unknown events or actions that occur outside the traditional intelligence cycle.

It can be argued that the Cuban Missile Crisis started rather innocuously in the summer of 1962 when the Soviet Union began transferring defensive weapons, including surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), to the Cuban government. This movement of arms became known to the Americans, but it drew little initial concern from the United States intelligence community. One notable exception to this general truth was Central Intelligence Director John McCone, who interpreted the presence of SAMs as part of a defensive system for offensive nuclear weapons. A Special National Intelligence Estimate was issued on 19 September 1962, which reflected the mainstream opinion. McCone criticized the CIA for displaying a lack of imagination when it came to the Soviet’s intentions.

McCone’s skepticism was partially correct: the Soviets decided at a later date to transfer nuclear warheads and tactical nuclear weapons to Cuba, but this decision had no direct connection to the SAMs. The continued presence of SAMs in Cuba after the Crisis had subsided led McCone to argue that the Soviets intended to reintroduce nuclear weapons at some future date. Interestingly, the Americans were never able to confirm or identify the presence of nuclear warheads in Cuba during the Crisis, but decided to operate under the assumption that such weapons had been delivered. Moreover, they never became aware of the presence of tactical nuclear weapons until the late-1980s, when the new Soviet state policy of glasnost allowed for greater openness, including the release of previously secret government records.

The American intelligence community received thousands of human reports with respect to the presence of Soviet long-range missiles (which would have been necessary to deliver the nuclear warheads) in Cuba from Cuban refugees, but many of these reports were easily discredited. Significantly, the majority of these reports failed to properly describe the missiles, and they were provided before the actual delivery of missiles to Cuba would have occurred. Having said this, the Americans received two accurate reports towards the end of September, and they decided to investigate the matter further through the use of U-2 reconnaissance aircraft. A desire to avoid offending the Soviets and poor weather conditions combined to delay the flights for two weeks. However, on 14 October 1962, the Americans finally confirmed the construction of long-range missile sites in Cuba through the use of aerial photographs. They kept this knowledge secret for one week before announcing it publically to the world, then catching the Soviets off guard.

Meanwhile, President John F. Kennedy issued two public warnings aimed at the Soviets on 4 September 1962 and 13 September 1962 respectively. Therein, he warned them not to ship ‘offensive’ weapons to Cuba. These warnings were the result of mounting domestic political pressures and should have clearly communicated the American’s position on nuclear weapons to the Soviet leadership, despite the fact that nuclear weapons were probably already present in Cuba by this time. Nonetheless, the Soviet leadership did not heed the warnings, and they continued with the transportation of offensive weapons to Cuba and the construction of offensive weapons delivery systems in Cuba.

Two subsequent Special National Intelligence Estimates were issued on 19 October 1962 and 20 October 1962, after the discovery of offensive weapons delivery systems in Cuba. These estimates did not vary greatly in detail, considering possible Soviet intentions and potential American responses. The two estimates ascribed an offensive purpose behind the Soviet’s actions, and this led to a more aggressive stance from the Americans. The three potential responses were: 1) a naval blockade; 2) an air strike; and 3) an invasion of Cuba. The National Security Council (NSC) was also created at this time; its Executive Committee (ExComm) being led by the president. The NSC and ExComm were meant to pool resources across the US intelligence community, and it is generally regarded as having succeeded in this respect at first.

The Soviets did not anticipate a naval blockade by the Americans—they assumed that the Americans would simply accept the missiles as part of the ‘game,’ and that the existing presence of the missiles would force the Americans to accept their continuing presence. Therefore, they were caught off guard when the Americans announced their knowledge of the missiles and their intention to set up a naval blockade on 22 October 1962 (the blockade would actually commence on 24 October 1962 at 10:00 A.M. EST). The Soviet leadership, in particular, Premier Nikita Khrushchev, considered ‘running’ the blockade, but ultimately decided against such a response.

At this point, an ostensible stalemate took place. The two main sides (i.e. the Americans and the Soviets) opened lines of communication between each other, but the Americans also began mobilizing their air forces as a precaution. The Soviets were aware of these mobilizations through satellite imaginary, and the Cubans became aware of the American’s contingency plans through human intelligence. Nonetheless, both the Soviets and the Cubans took the American contingency plans to represent their actual plans, and it is commonly argued that this led, in part, to the sudden willingness on Khrushchev’s part to negotiate a settlement on 28 October 1962. Although this general account of the conclusion to the Crisis is accurate, it glosses over several important events that took place between 22 October 1962 and 28 October 1962. Likewise, it downplays some of the lingering issues that were not resolved until much later.

Among these other events were two letters sent by Khrushchev on 26 October 1962 and 27 October 1962, as well as a series of authorized and unauthorized backchannel communications. The first letter sent by Khrushchev was conciliatory in tone, and it laid out many of the concessions that would form the final settlement. In contrast, the second letter, which was sent mere hours after the first, was aggressive in tone, and it demanded the withdrawal of American missiles from Turkey. In preparing their reply to the first letter, the Americans were surprised by the sudden change of tone, and they decided to ignore the second letter.

The origin of the letters is often attributed to an unauthorized backchannel communication between Soviet embassy counselor Aleksandr Fomin and ABC News correspondent John Scali. Fomin was instructed to make contact with the Americans by Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, who was not informed of the Soviet plan to place missiles in Cuba until after it became common public knowledge. The positive response expressed by Scali is read by many to have pushed the Soviets for further concessions. However, Fomin’s encounter would not have reached Moscow in time for Khrushchev’s first letter, meaning the Soviets were already prepared to offer serious concessions. In response to the second letter, Scali met once again with Fomin. This time, he was instructed to offer a firmer message for the Soviets. It is this message that many now believe led the Soviets and the Cubans to believe the Americans were preparing for a full-scale attack. The fact that Soviet SAMs shot down a U-2 reconnaissance aircraft around the same time only added to the sense of alarm felt by all sides.

The idea of trading missiles in Turkey for those in Cuba, however, actually originated through parallel backchannel communications between Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Ambassador Dobrynin on 27 October 1962. Other members of ExComm, apart from the President, were not aware of these talks. For this reason, any exchange of missiles was generally understood to be part of a separate settlement. Khrushchev may have misunderstood this point, but the other major players were aware of it. Finally, between 26 October 1962 and 28 October 1962, the Soviets and the Cubans acquired reports of the Americans downgrading their plans to attack. This may have led to greater confidence in the Soviet-Cuban camp, but subsequent reports reiterated the expectation of an immediate attack. Such a sudden change in intelligence could have pushed the Soviets closer towards settlement, even if the Cubans read it as cause for a pre-emptive attack.

Finally, the Cuban Missile Crisis did not terminate on 28 October 1962. As partial payment for their co-operation, the Cubans demanded that a small show of Soviet force remain in Cuba. This force was meant to act as a ‘tripwire’ in the event of any future American attack, and it went directly against the agreed upon settlement. In fact, a small Soviet combat brigade of 2500 men remained in Cuba until their discovery in the summer of 1979, which caused a mini-crisis. Moreover, the Soviets tried to exploit the difference between ‘offensive’ and ‘defensive’ weapons, but the Americans were generally effective in denying this difference.

Intelligence Models in Practice

The Cuban Missile Crisis offers an ideal case through which to test the three intelligence models discussed above. For instance, all the models appear to have some degree of difficulty incorporating ‘outside’ events or actions, such as the secret backchannel communications between Attorney General Kennedy and Ambassador Dobrynin, into their workflows. A corollary of this shortcoming concerns the generally-stated relationship between policymakers, analysts, and collectors. While there were somewhat even and ongoing interactions between these three types of intelligence actors at the beginning of the crisis, towards the end, policymakers such as President Kennedy and Attorney General Kennedy assumed sole ownership of the issue. Furthermore, they began to actively perform the roles of analysts and collectors themselves, problematizing the conceptual categorization of separate intelligence activities based upon separate intelligence actors. In this sense, the true nature of hierarchical power is not properly captured by any of the models. Their general focus upon interactions between policymakers, analysts, and collectors obscures the fact that the degree to which this relationship is truly interactive depends upon policymakers. Likewise, it obscures the fact that policymakers alone can perform all three roles.[9]

In terms of the particular intelligence models, Figure 1.1 indicates that the cyclical model fails to incorporate outside events or actions, presenting itself as a closed process. This is problematic for the reasons already addressed. The same model also suggests an overly linear process in that instructions proceed unidirectionally from policymakers to analysts and collectors. Such a depiction ignores the reality of interaction between these three actor types. Although the true nature of their relationship is by no means ideal or equal, it can prove complicated. For example, collectors may communicate with analysts to get a better sense of their needs. This point can be directly related to the American surveillance of Soviet missile sites in Cuba during the Crisis. Here, collectors were actively photographing the pace of construction, providing analysts a better sense of the actual threat posed by the missiles, based upon feedback. Finally, the cyclical model succeeds in recognizing hierarchy within the intelligence process, but it arranges policymakers, analysts, and collectors in a way that overstates their independence. As demonstrated, policymakers enjoy the unique capacity to bypass analysts and collectors, or to unilaterally assume their roles.

Figure 1.2 shows that the target-centric model encounters some of the same problems as the cyclical model. However, it also encounters some additional problems, based upon its target-centric nature. First, alongside the cyclical model, the target-centric model fails to incorporate outside events or actions, and it overstates the reciprocal nature of the intelligence process, albeit in greater excess. A cursory glance at the model would suggest a nearly equal, symbiotic relationship between policymakers, analysts, and collectors, but actual experience, as exemplified by the Cuban Missile Crisis, proves otherwise. Once again, it bears mention that policymakers enjoy considerable influence, authority, and autonomy over the other actors involved in the intelligence process. Second, the target-centric model presupposes that a clear intelligence target already exists. This was not the case with respect to the Cuban Missile Crisis. The American government scrambled to build such a target after it became known that the Soviets were building long-range missile sites in Cuba. Thus, the importance of long-term, forward thinking and investment implied by the target-centric model may reflect an expectation that is set too high for actual practice. On the other hand, the target-centric model allows for greater interaction among policymakers, analysts, and collectors than the cyclical model, which serves as its greatest strength.

In comparison to the other two intelligence models, the multi-layered model represents a highly complex account of the intelligence process. This can be seen in Figure 1.3. While this might seem like a fault, it actually serves to positively distinguish the model. The multi-layered model, for instance, allows for interaction between policymakers, analysts, and collectors in myriad ways, injecting a critical sense of discretion and contingency into the intelligence process. Furthermore, this quality of contingency is better able to incorporate outside events or actions than the cyclical model and the target-centric model. Taken together, the qualities of discretion and contingency can account for the obscured activities of Attorney General Kennedy and Ambassador Anatoly, linking them to the larger intelligence process. A fault of the multi-layered model, however, concerns its overall complexity, which makes it a poor heuristic. Although valid, this criticism is belied in part by the fact that the intelligence process itself demonstrates great complexity. Thus, the multi-layered model, through its own complexity, closely approximates actual practice. For intelligence practitioners and scholars, this should be seen as the key strength of the model.

Conclusion

This brief article has attempted to outline the respective strengths and weaknesses of three prominent conceptual models in the world of intelligence, namely, the cyclical model, the target-centric model, and the multi-layered model. In pursuing this aim, it drew upon the real-world example of the Cuban Missile Crisis. To some extent, all the models encountered difficulty incorporating outside events or actions into the intelligence process. They also had difficulty conceptualizing the true relationship between policymakers, analysts, and collectors, but this might be a fault of any intellectual exercise that seeks to impose clear meanings upon highly fluid and oftentimes ambiguous workflows. Separately, the cyclical model is guilty of presenting a linear account of the intelligence process and of downplaying the full effect of hierarchy within this process; the target-centric model is guilty of both these faults, in addition to overemphasizing the availability of advanced knowledge; and the multi-layered model is guilty of being overly complex. Nonetheless, given the overall complexity of the intelligence profession, this ‘fault’ of the multi-layered model is actually the model’s key strength, in that it provides a truer sense of the intelligence world. Therefore, although it is far from an ideal heuristic, the multi-layered model appears to be the best conceptualization of the intelligence process available to practitioners and scholars.

[1] Kurt Jensen, who teaches intelligence studies at Carleton University, is due special mention and thanks for guiding me through this project. Without him, the secrets of the world would still be secrets to me.

[2] Robert M. Clark, Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach, 4th edition. (Los Angeles: CQ Press, 2013), pp. 4–7.

[3] Ibid., pp. 46–54.

[4] Mark M. Lowenthal, Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, 5th edition. (Los Angeles: CQ Press, 2012), p. 67.

[5] Clark, p. 10.

[6] Lowenthal, p. 69.

[7] For example, see Raymond L. Garthoff, “Cuban Missile Crisis: The Soviet Story,” in Foreign Policy, Issue 71 (Autumn 1988) and “US Intelligence in the Cuban Missile Crisis,” in Intelligence and National Security, Volume 13, No. 3 (September 1998).

[8] These sources include Arnold L. Horelick, “The Cuban Missile Crisis: An Analysis of Soviet Calculations and Behavior,” in World Politics, Volume 16, No. 3 (April 1964); Bruce J. Allyn, James G. Blight, and David A. Welch, “Essence of Revision: Moscow, Havana and the Cuban Missile Crisis,” in International Security, Volume 14, No. 3 (Winter 1989–1990); Len Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War: Lessons from History (New York: Continuum, 2007); and Roger Hilsman, The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Struggle Over Policy (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996).

[9] Obviously, an analyst can perform the role of a collector and vice versa, but neither can perform the role of a policymaker without first being given the authority of a policymaker. This point relates to the leading position of policymakers in the overall intelligence process. See Lowenthal, pp. 1–9, for an expanded discussion on the true relationship between these three actor types in the intelligence profession.