Making Waves: Aiding India's Next-Generation Aircraft Carrier

5 May 2015

By Ashley J. Tellis for Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

This is an excerpt of the external pageoriginal articlecall_made, first published on 22 April 2015 by the external pageCarnegie Endowment for International Peacecall_made.

Introduction

Ever since the conclusion of the 2005 U.S.-Indian Civilian Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, many policymakers have wondered what the next big idea to transform bilateral ties might be. Clearly, no successor initiative could ever replicate the momentous character of the nuclear accord because it implicated core national security policies in both countries and removed the singular disagreement that had kept them at odds for over thirty years. Yet there exists presently a remarkable opportunity that holds the promise of making new waves in bilateral collaboration—in the best sense—if only Washington and New Delhi are imaginative enough to grasp it: jointly developing India’s next-generation aircraft carrier. Working in concert to develop this vessel would not only substantially bolster India’s naval combat capabilities but would also cement the evolving strategic bond between the United States and India in a truly spectacular fashion for many decades to come.

No country today possesses the technical capacity to design and build aircraft carriers like the United States. And no country today would profit as much from collaborating with the United States in carrier design and construction as India at a time when its local dominance in the Indian Ocean is on the cusp of challenge from China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), which commissioned its first aircraft carrier in 2012. If the United States were to partner with India now in developing its next large-deck carrier, tentatively christened Vishal—the first in a series of standardized designs that would eventually replace both the current Russian (INS Vikramaditya) and British (INS Viraat) hand-me-downs in the fleet as well as the indigenous Vikrant scheduled to enter service in 2018—it will have contributed mightily to helping the Indian Navy meet the emerging Chinese naval threat while simultaneously becoming a net provider of security in the Indian Ocean. U.S. assistance would also send a powerful signal to China and to all the other littoral states that U.S.-Indian defense cooperation is intended to advance their highest mutual national interests, including preserving, as former U.S. secretary of state Condoleezza Rice once phrased it, an Asian “balance of power that favors freedom.” And, finally, it would convey to important—but still skeptical—Indian audiences, especially in the military, that the United States can collaborate with India on vital projects of strategic import in ways that only Russia and Israel have done thus far.

Factoring such considerations, U.S. Senator John McCain, in a September 9, 2014, address at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, challenged the U.S. and Indian governments to expand their defense cooperation to include “more ambitious joint ventures, like shipbuilding and maritime capabilities, even aircraft carriers.” This vision was realized during U.S. President Barack Obama’s January 2015 visit to India when the two nations agreed to “form a working group to explore aircraft carrier technology sharing and design.” That this accord finally came to fruition was owed largely to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi: disregarding the reservations of some of his senior advisers, and appreciating the singular proficiency of the United States in carrier design, construction, and operations, Modi chose to accept the U.S. offer of partnership and, accordingly, authorized the conclusion of deliberations that had begun during his September 2014 visit to the United States. In so doing, Modi was guided by a clear recognition of the importance of the Indian Ocean for both India’s prosperity and its security—and by his conviction that a strong navy, with the most capable afloat aviation possible, was essential for the realization of India’s strategic aims.

The door has thus been opened for genuine U.S.-Indian collaboration in developing India’s next-generation aircraft carrier. Consummating this aspiration, however, will require the two sides to think ambitiously. This implies partnering in everything from vessel design to physical construction to sea trials so that the Indian fleet may finally commission the most formidable man-o’-war possible. The Indian Navy, undoubtedly, will lead this effort, which is already under way: its Naval Design Bureau has completed the technology assessment, feasibility studies, and analysis of alternatives, and is now deeply immersed in activities relating to engineering design. At this point, there is a quickly closing window of opportunity for a comprehensive partnership with the U.S. Naval Sea Systems Command and, as appropriate, with U.S. private industry. Such an accord would bestow great dividends because the wealth of American experience in overseeing the construction of large-deck carriers cannot but benefit the Indian Navy before it finalizes its production design.

What the Indian sea service should not do is succumb to the temptation of making bilateral cooperation merely an exercise in procuring technologies, such as the electromagnetic aircraft launch system (EMALS), which it has long eyed for its future “flattops.” If this remains its only ambition, the fecund collaboration otherwise possible will degenerate into a transactional activity centered on releasing export licenses and consummating discrete procurement deals at the American and Indian ends, respectively. While even such modest interactions would undoubtedly produce a better Indian capital ship, they would constitute a huge opportunity lost in deepening the strategic partnership with the United States. Even worse, New Delhi will have foregone the potential of developing the most formidable aviation-capable vessel possible.

The Strategic Context Underlying Indian Carrier Capabilities

The Indian Navy has been one of the few fleets to deploy aircraft carriers continuously for more than fifty years. But while this ship retained pride of place in the service’s force architecture, it did not have incontrovertible utility when India was largely an inward-looking state. Until the end of the Cold War, the Indian economy enjoyed tenuous links with the global trading system, India’s local adversaries—Pakistan and China—did not constitute major naval threats, the extraregional powers operating in the Indian Ocean largely left India alone, and New Delhi’s power-political weaknesses implied that, despite the rhetoric, India’s strategic interests did not extend far beyond its subcontinent. Consequently, aircraft carrier deployment lacked the value it otherwise might have had if India’s geopolitical circumstances had been different.

Thankfully for the navy, however, India’s fortunes are changing dramatically for the better—and the emerging strategic environment promises to reward the fleet for preserving its proficiency in carrier operations over the years. Increasing Indian economic growth recently has produced greatly expanded maritime trade, and India’s rising national power has sensitized New Delhi to its larger interests throughout the vast Indo-Pacific region—from the east coast of Africa to the Persian Gulf to the Southeast Asian straits and even beyond, to the distant East Asian rimlands. As Prime Minister Modi summarized it succinctly in a March 12, 2015, external pagespeech in Mauritiuscall_made, “India is becoming more integrated globally. We will be more dependent than before on the ocean and the surrounding regions. We must also assume our responsibility to shape its future. So, [the] Indian Ocean region is at the top of our policy priorities.” Reinforcing this conviction, the United States is also eager to see India assume a larger role in this strategic space. But most important of all, the PLAN now appears poised to operate consistently in the Indian Ocean, thus giving the traditional terrestrial rivalry between China and India a new and more serious maritime twist.

The prospect of a major Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean challenges Indian security in novel ways, transforming a hitherto secure rear into a springboard from which coercive power can be brought to bear in new directions against the Indian landmass. Thanks to its antipiracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden, Beijing has already taken the first steps toward maintaining a near-continuous presence in the western Indian Ocean. Chinese nuclear and conventional attack submarines have recently undertaken their first operational cruises in the wider basin, and, since 2012, Chinese auxiliary general intelligence ships have systematically conducted oceanographic and bathymetric surveys, almost certainly as a prelude to major (and perhaps regular and extended) deployments of Chinese carrier battle groups (CVBGs), surface action groups, and nuclear attack submarines in the future.

In this context, perhaps no event would be more catalyzing than the appearance of a Chinese aircraft carrier and its associated escorts in the Indian Ocean. Because carriers make a qualitative difference to the kind of sea control that can be exercised by a nation in support of both gunboat diplomacy and power projection, such a Chinese vessel operating in the vicinity of the Indian peninsula would vivify the heightened naval dangers to New Delhi. The possibility of such a presence, especially during a crisis or a conflict, would justify the acquisition of various instruments intended to neutralize it—with the most obvious counters being land-based airpower, attack submarines, and of course carrier aviation itself.

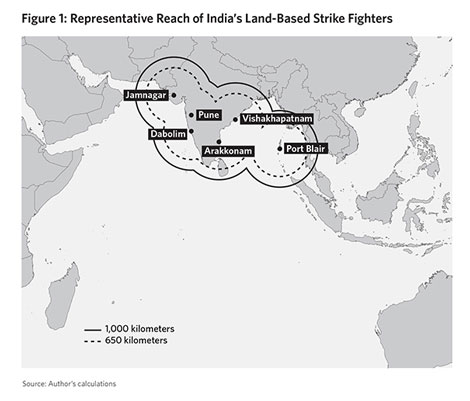

India’s favorable geography makes land-based airpower a particularly potent instrument in dealing with any future Chinese aircraft carrier in the Indian Ocean. But this solution is most viable only in relative proximity to the Indian coastline. Unless India acquires a dedicated bomber contingent, its best strike fighters today (the Su-30MKI, for example) have useful operating radii of 650–1,000 kilometers (400–620 miles) from their home bases, depending on the missions and flight profiles involved. Air refueling can, depending on tactical circumstances in the Indian context, extend these ranges by some 25 to 30 percent. But it cannot compensate for the critical limitations that afflict land-based fighters in general: the increased but unproductive mission time required to reach far-flung targets compared to potentially nearby carrier airpower, not to mention the operational delays incurred when important targets have to be reattacked because of mechanical failures or successful enemy interception.

As a rule, therefore, the farther away military action occurs from the Indian peninsula, the more indispensable carrier aviation becomes (see figure 1). Preparing for such a contingency is, in fact, utterly reasonable because if a PLAN flotilla in the Indian Ocean is to be parried by force, Indian naval strategists would seek to neutralize it as far away from their homeland as possible. Furthermore, if Indian commerce from Europe, Africa, and the Far East has to be protected along the country’s sea lines of communication at great distances from the mainland, an Indian CVBG would be invaluable.

These carrier capabilities, however, would also have great utility closer to the Indian landmass in any major crisis or conflict involving China because it is possible, even likely, that the Indian Air Force (IAF) could be unavailable due to its commitment to air defense and ground attack along the disputed Himalayan border—far away from India’s maritime frontiers. Even if IAF assets were available, carrier-based capabilities would be highly desirable because they would complicate PLAN operations by forcing the Chinese fleet to guard against attacks from its seaward side, even as it coped with threats emanating from the Indian peninsula.

The case for a capable contingent of quiet nuclear attack submarines to deal with the emerging Chinese challenge in the Indo-Pacific has never been stronger. Indian attack submarines will invariably prove to be formidable in the countercarrier role—with nuclear vessels having advantages in speed and endurance over their conventional counterparts, assuming they meet the appropriate quieting thresholds. But their ready availability for this mission cannot be presumed, given their expected small numbers in the Indian inventory, their likely commitment to anti-submarine warfare (ASW) missions (including possibly in support of the Indian CVBG), and their preoccupation with other tasks that may be essential in a conflict. If India is to deploy a subsurface force capable of undertaking the silent high-speed runs necessary to intercept a fast-moving surface flotilla without being detected, while also being capable of conducting at other times the ultraquiet operations associated with anti-submarine and acoustic intelligence collection missions, it will need to acquire additional Russian submarines with acoustic stealth levels of the Improved Akula I- or Akula II-class nuclear submarines or better—rather than the leased Akula I currently in service.

At any rate, the Indian Navy has already determined that it requires land-based airpower and nuclear attack submarines as a complement to—but not as a substitute for—its aircraft carriers when dealing with the dangers posed by a Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean over the long term, because of the myriad benefits of possessing organic naval aviation for other wartime and peacetime contingencies. The central analytical task, then, consists not of evaluating the desirability of aircraft carriers relative to the alternatives, but rather of identifying how the United States and India should cooperate to develop the kind of next-generation carrier capabilities that New Delhi deems desirable.

The principal objective that should guide bilateral cooperation in carrier development is the need to ensure that India’s next-generation aircraft carrier—to include its air wing and its capacity for combat operations—will be superior to its Chinese counterparts. China has been a late entrant into carrier aviation, but it appears determined to make up for lost time. Beijing currently deploys an extensively refurbished Kuznetsov-class vessel of approximately 65,000 tons, the Liaoning, which is likely to serve as the baseline for its future carrier forces. The Liaoning, now used mainly for training missions, is larger than the INS Vikramaditya, a Kiev-class ship of about 45,000 tons. But both vessels, being formerly Soviet aviation cruisers, are only capable of short take-off but arrested recovery (STOBAR) operations: the deployed aircraft launch under their own power using a ski ramp for added lift, but they use arresting cables to terminate their landing run when returning to the ship.

After building its first indigenous carrier, the Vikrant, as a relatively small STOBAR platform, the Indian Navy has sensibly decided that its successor will be a larger, approximately 65,000-ton vessel capable of catapult-assisted take-off but arrested recovery (CATOBAR) aviation operations. This is indeed a wise choice because, given the vast ocean areas of interest to India and the expectation that its CVBGs will have to operate more or less independently, such carriers can host larger air wings composed of high-performance fighters capable of carrying heavy ordnance loads, integrate the requisite number of support aircraft, and mount substantial cyclic air operations, meaning the rapid launch and recovery of aircraft.

A carrier larger than the ship currently contemplated might have been even better because it would have had the capacity to host an even bigger air wing in comparison to its Chinese competitor. But so long as the Indian vessel can conduct CATOBAR air operations, in contrast to China’s STOBAR-only capabilities, the Indian Navy will still retain the edge. Together with the superior training, doctrine, and other complementary capabilities that India now possesses, such a carrier capability would improve the Indian Navy’s chances of securing sea control even against an otherwise formidable Chinese opponent operating in the Indian Ocean region.

The laws of physics only make large carriers a more sensible choice for India, given its vast operating areas and its diverse operational objectives, which include air warfare, anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface warfare, mine warfare, amphibious warfare, and land-attack operations. For starters, it is more economical, in terms of installed horsepower per ton of displacement, to propel a larger vessel at 30-plus knots than a smaller one. And, thanks to the square-cube law, an aircraft carrier’s useful hull volume increases at a rate greater than its structural weight, thus allowing for a balanced design that maximizes flight deck size; expands the number of aircraft that can be carried; increases the size of the armored box that protects ordnance, propulsion, command and control, and other vital spaces; and in general improves passive protection throughout the ship. At the end of the day, however, the large carrier’s greatest advantage is its potential for increased sortie generation and, by extension, higher-tempo cyclic operations, which permit the force to unleash greater firepower relative to its opponent.

If it is assumed, as a rule of thumb, that one aircraft can be spotted on a carrier for every 1,000 tons of displacement, the navy’s Vishal-class ships will be able to routinely host a notional air wing of at least some 50 aircraft (the smaller number allowing for safety margins): 35 strike fighters, three airborne early warning (AEW) platforms, eight ASW and utility helicopters, and four support aircraft, aerial tankers, or electronic warfare (EW) platforms. Over time, a squadron of unmanned combat aerial vehicles—for particularly dangerous tasks such as the suppression of enemy air defenses or for long loiter missions such as reconnaissance and surveillance—would be plausible as well.

An Indian carrier air wing hosting high-quality assets in such numbers would represent significant combat capabilities, especially when the weapons and sensors of its escorts are factored into the equation. A CVBG of this kind would be able to conduct air, surface, and anti-submarine warfare operations simultaneously against all regional adversaries as well as against any future Chinese carrier operating STOBAR aviation in the Indian Ocean. When the Indian Navy finally deploys the three Vishal-class vessels it hopes for, these capabilities will only expand further, enabling its CVBGs to hold their own against future Chinese CATOBAR carriers operating in proximity to India, while undertaking additional responsibilities such as supporting amphibious and mine-warfare operations as well as executing significant land-attack missions with tactical aviation against any local competitor. Success in all cases will still depend on a broad range of continental capabilities, to include shore- and space-based sensors along with long-range maritime patrol aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles. But the combat power embodied by such large-deck carriers will bestow on the Indian Navy a capacity for extrapeninsular sea control that it has not enjoyed before.

To continue reading, please external pageclick herecall_made.