An Unnoticed Crisis: The End of History for Nuclear Arms Control?

6 Jul 2015

By Alexei Arbatov for Carnegie Moscow Center

This is an excerpt from a paper which was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCarnegie Moscow Centercall_made on 16 June 2015. The full paper is available external pageherecall_made.

Beginning with the signing of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963, an international arms control regime has limited existing nuclear arsenals and prevented further proliferation of nuclear weapons. But that entire system could soon unravel. Nearly all negotiations on nuclear arms reduction and nonproliferation have come to a stop, while existing treaty structures are eroding due to political and military-technological developments and may collapse in the near future. These strategic and technical problems can be resolved if politicians are willing to work them out, and if experts approach them creatively.

A Steady Erosion

- Problems other than nuclear arms control dominate the security agenda of the polycentric world.

- Political momentum facilitated negotiations and agreements between Russia and the United States in the 1990s and during a brief reset period between 2009 and 2011. But renewed confrontation and curtailed cooperation between the two countries since then have undermined progress.

- With the disintegration of the nuclear arms control regime, threats of and plans for the combat use of nuclear forces will return to the strategic and political environment.

- Mutual mistrust, suspicion, and misunderstanding among nuclear states will also increase, which may lead to a fatal error in a crisis, with grave consequences.

What World Powers Can Do To Revive Nuclear Arms Control

Forge a unified position. Only political unity among the major global powers and alliances, coupled with urgent and effective action, can reverse the trend of disintegration and help to avoid the “end of history” of nuclear arms control.

Preserve existing treaties. The 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty should remain in effect to limit offensive nuclear weapons.

Set new goals. Because total nuclear disarmament is a distant aim, the parties’ immediate goals should be less ambitious and more suited to the existing—and far from ideal—world order.

Explore a range of options and angles. Objectives could include achieving the next step in reducing the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals on a bilateral basis after 2020, unconditionally committing to a no-first-use policy for nuclear weapons, mutually lowering the alert levels for all legs of strategic forces in a verifiable manner, and transforming the bilateral arms control process into a multilateral one.

Introduction

The Ukrainian conflict and wars in the Middle East, which have captured the spotlight for over a year, have overshadowed other international security challenges. One victim of this preoccupation has been a creeping crisis over the international arms control regime. It has not claimed any lives yet. But should this crisis continue to expand, the entire system of limiting existing nuclear arsenals and preventing further proliferation of nuclear weapons could unravel, with consequences far more devastating than the crisis in Ukraine.

For over fifty years, starting with the signing of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963, the world has had in place a legally binding framework for controlling the most devastating weapon ever invented by mankind. There is now a real and unprecedented possibility that this framework will disintegrate. Even more striking is that this risk has arisen a quarter of a century after the end of the Cold War—an event that gave rise to hopes that the risk of nuclear disaster would forever remain in the past, and that nuclear disarmament would turn from a utopian vision into military-political reality.

The progress achieved in April 2015 at the talks between the P5+1—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States plus Germany—and Iran is the only bright spot on the nuclear negotiations landscape, though a final deal has yet to be reached. All other negotiations on nuclear arms reduction and nonproliferation have come to a dead end. The existing treaty regimes are eroding under the weight of political and military-technological developments and may collapse in the near future. In particular, even as the two key agreements between Russia and the United States to limit offensive nuclear weapons—the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty—are still being observed, their future is in doubt.

Crisis Symptoms

The crisis of arms control is both multifaceted and comprehensive. The United States has abandoned the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and no longer accepts any restrictions on its missile defense deployments. It has not ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) almost two decades after negotiations concluded. For the foreseeable future, there is little prospect of the United States accepting new obligations. At the same time, the United States has accused Russia of violating the INF Treaty. As a result, Republicans in the U.S. Congress have argued for retaliating by renouncing the treaty and even by withdrawing from New START.[i]

Russian officials, for their part, have openly questioned the value of the INF Treaty and also raised the possibility of withdrawing from it. [ii] At the same time, nongovernmental political and strategic analysts in Russia have discussed the possibility of abandoning New START and the CTBT. The most radical voices among them have gone so far as to propose that Russia withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in order to sell and service nuclear weapons abroad.[iii]

Meanwhile, the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program to eliminate Russian nuclear and chemical weapons and to decommission Russian nuclear submarines was ended in 2013. The next year, Russia and the United States decided to discontinue their cooperation on the safety and security of nuclear facilities and materials. For the first time, Moscow has refused to participate in the next Nuclear Security Summit, which will be held in Washington in 2016.

It appears that many parliamentarians, influential politicians, and civic organizations in both the United States and Russia have embarked on a course of destruction of everything that state leaders, diplomats, and militaries have so painstakingly built in this realm over several decades.

Apart from the two nuclear superpowers, the other seven states with nuclear weapons are as reluctant as ever to join the disarmament process and limit their arsenals. Negotiations toward a Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty—an agreement to achieve the rather peripheral goal of preventing the new production of fissile material for weapons—have been deadlocked for many years and their prospects remain bleak. A conference to discuss the establishment of a weapons of mass destruction-free zone in the Middle East has been postponed for several years in a row.

The nonproliferation regime too is in disarray. The P5+1 talks have produced a general outline of a long-term agreement to limit Iran’s nuclear program, but the framework has encountered strong opposition in the U.S. Congress from Republicans and Democrats alike. It has also come under criticism in Tehran. The 2015 NPT Review Conference ended in failure. This state of affairs, along with North Korea’s increasing nuclear potential (the country withdrew from the NPT in 2003 and has since conducted three nuclear tests), exerts a growing pressure on the NPT and its regime and institutions.

The history of nuclear arms control has endured periods of stagnation and setbacks before, and some of these were quite lengthy. The Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty II (SALT II) and START II never entered into force, and the CTBT is still waiting to do so. Negotiations over START III weren’t completed. The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty was even abrogated. But the current period of disintegration is unprecedented, with literally every channel of negotiation deadlocked and the entire system of existing arms control agreements under threat. The lack of attention to this situation from the great powers is also unprecedented, but it fits within the drastic deterioration in broader relations between Russia and the United States.

There is no question that the crisis in Ukraine and the crisis over nuclear arms control complement and exacerbate each other politically. However, there is no direct connection between them. The nuclear arms control crisis started much earlier and has its own origins. A peaceful resolution of the Ukraine problem could potentially create a more favorable climate for nuclear arms control. But it would not resolve a host of other political, strategic, and military-technological challenges, all of which are deep-rooted and together have precipitated the current nuclear crisis. To resolve these issues, the parties will have to understand the causes of the present crisis, formulate new concepts of strategic stability, and reevaluate the role, priorities, and methods of limiting existing nuclear arsenals and preventing the further proliferation of nuclear weapons.

World Order Change

As paradoxical as it might seem, nuclear arms control was an integral part of the Cold War world order. However, this dialectical relationship did not appear immediately, at the outset of the Cold War, or on its own. It took a series of dangerous crises (the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis being the riskiest one) and several cycles of an intensive and extremely costly arms race for the Soviet Union and the United States to realize the dangers they faced and the need for practical steps to prevent a global catastrophe. Nuclear arms control treaties became a top priority of their relationship and of international security more generally.

At that time, international politics was largely shaped by the global competition between the two superpowers. The possibility of a deliberate or accidental nuclear war was the main threat to international security. As a result, efforts to limit and reduce the two superpowers’ nuclear arsenals on the basis of parity (and, subsequently, strategic stability) became the major pillar of common security and the world order after the late 1960s.

The concept of strategic stability formalized the relationship of mutual nuclear deterrence based on each side’s devastating second-strike capability; it also led to mutual incremental reductions of nuclear arsenals. This approach to arms control was consistent with a “managed” Cold War, which was characterized by harsh rivalry in zones that were outside of tacitly recognized spheres of U.S. and Soviet interest, coupled with mutual efforts to avoid a head-on, armed confrontation. Nuclear nonproliferation played a subordinate role in that arrangement, but it was required because it was commonly acknowledged that reductions in the numbers of U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons would have been impossible if the number of nuclear-weapon states had increased.

Two changes that no one could have anticipated at the time occurred with the end of the bipolar confrontation and the arms race by the late 1980s. First, relations between Russia and the United States gradually lost their central role in global politics. Second, nuclear arms control ceased being the major pillar of international security.

The first change resulted from the collapse of the Soviet Union as both an empire and a social-ideological system. With the gradual emergence of the polycentric world, other power centers assumed an increasingly important role—China and the European Union (EU) became global players, and Brazil, India, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey became regional ones. Nuclear arms control did not figure prominently in their foreign policy interests and security concepts, if at all.

In the nearly quarter century since the end of the Cold War, the United States (frequently with aid from its allies) has actively tried to create and take charge of a unipolar world order. Its actions when trying to resolve regional conflicts (in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and the former Yugoslavia), build a new system of European security (through poorly judged North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO, and EU expansions), and limit and prevent the spread of nuclear weapons have often led to substantial harm. Russian President Vladimir Putin has spoken repeatedly—and quite eloquently and emotionally—about the negative consequences of the actions of the United States and the West in general, including in Munich in 2007 and Sochi in 2014. [iv]

But despite its best efforts, the United States’ ability to affect the course of world events (even with help from NATO) has been declining steadily. The West has also been less and less willing to bear the material and human costs of its involvement in regional conflicts, as evidenced by its operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria.

The second shift—the declining importance of arms control in international security—resulted from the fact that the transition from confrontation to cooperation between the two superpowers all but eliminated the fear of the threat of nuclear war between them. This change put the spotlight on the economy, climate change, resources, migration, and the other challenges of globalization, as well as such security concerns as local ethnic and religious conflicts, international terrorism, drug trafficking, and other types of transnational crime. The only high priority nuclear-related concern to attract attention was proliferation.

For some time, the momentum generated by the unprecedented improvement in relations between the Soviet Union/Russia and the West compensated for the implications of these two shifts for arms control. The former adversaries made serious progress on disarmament, which became a symbol of their military-political rapprochement; in particular, they achieved unparalleled transparency and predictability in the main component of their armed forces—strategic nuclear forces (SNFs).

Meanwhile, enormous Cold War-era weapon stockpiles were cut by almost an order of magnitude (counting tactical arms reductions), significantly reducing the risks of losing control over nuclear arms and of accidental launches. These threats were also mitigated by the withdrawal of tactical and strategic nuclear weapons from the territories of the former Soviet and Warsaw Pact states and their transfer to Russia, where they were dismantled.

Thus, as mutual trust increased, the role of nuclear disarmament in bilateral relations decreased. Later on, this dialectical relationship would be broken.

Nevertheless, following the breakthroughs of the first decade after the Cold War, from 1987 to 1997, and the start of a new phase in global politics, the process of nuclear disarmament continued drifting toward the periphery of international security, while its goals and desirable next steps were becoming less obvious. Even in Russian-U.S. relations, nuclear arms reductions were playing a significantly less important role than during the Cold War.

This trend became especially pronounced during the administration of former U.S. president George W. Bush, between 2001 and 2009. During that period, U.S. officials argued that arms control between the United States and Russia was a “Cold War legacy”: arms control agreements were for adversaries, and partners and friends had no need for them even if they possessed nuclear weapons. To make this point, the example of France, the United Kingdom, and the United States was usually cited (disregarding the fact that these countries were NATO allies, whereas Russia was not invited to join the alliance during the 1990s or any time afterward).

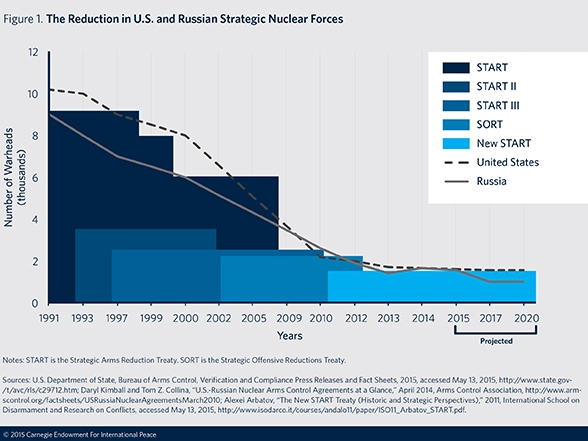

In 2002, the United States withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which had been the cornerstone of the strategic weapon limitation process for the previous thirty years. The Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT), signed in 2002, was never fully functional because the parties failed to agree on counting rules and verification provisions; the United States demanded maximal allowances and minimal restrictions. [v] And the agreements that have followed the unprecedented reductions of START I called for increasingly marginal reductions in SNF levels (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The Reduction in U.S and Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces (click to enlarge)

Notwithstanding all the declarations of friendship and partnership between the United States and Russia, the two countries have failed to formulate a coherent alternative to the concept of mutual nuclear deterrence based on the principles of strategic stability (mutually assured destruction through a second-strike capability). Meanwhile, during the first decade of the twenty-first century, the two powers retained a total of almost 10,000 nuclear warheads deployed in their combat-ready SNFs and in storage (including substrategic arms) that were primarily assigned missions against each other and their allies.

Neglect of nuclear arms control and the prolonged stagnation in the negotiation process during the decade from 1998 to 2008 have had harmful effects. With START I about to expire in 2009, the parties suddenly realized that there was nothing to replace it: the START II, START III, and SORT agreements were not properly ratified or finalized. Therefore, it fell to the administrations of U.S. President Barack Obama and then Russian president Dmitry Medvedev to hastily work out New START (also known as the Prague Treaty), which effectively legitimized the SNF levels agreed upon in SORT eight years earlier (around 2,000 deployed warheads, by actual force loading, in contrast to agreed counting rules that defined each heavy bomber as one delivery vehicle and one warhead). That treaty was an important achievement in preventing the collapse of the central pillar of nuclear arms control and ensuring strategic transparency and predictability for another decade—until 2020.

However, further progress proved impossible—marking a sharp difference from the past, when, upon the signing of every new treaty, each side had its own agenda for the follow-on agreement. An attempt to continue the process was made by President Obama in a 2013 speech in Berlin, in which he called for a further 30 percent reduction in nuclear warheads, down to about 1,000 for each side. However, the proposal was not welcomed in Moscow for political and strategic reasons.

At first glance, the concept of mutual nuclear deterrence sounds quite reasonable. Indeed, during the Cold War era, it was the preferable alternative to the traditional idea of actually using the full extent of one’s military might to achieve victory over an adversary, which in the nuclear age would have led to a disaster. However, the concept also has something apocalyptic about it: states base their security on the mutual capability and readiness to kill tens of millions of each other’s citizens and destroy centuries of civilization in a matter of hours.

The events of 1998–2008 demonstrated that, in the absence of active arms control efforts, a good political relationship between Russia and the United States, which had continued well into the mid-2000s, did not automatically eliminate the harsh strategic reality of mutual nuclear deterrence—regardless of how much it was sugarcoated by political declarations. Having been essentially ignored, this military reality, along with other factors, ultimately undermined political relations between Russia and the United States at the end of the first decade of the new century.

The inability of the two powers’ political and expert communities to elaborate realistic alternatives to mutual nuclear deterrence and realize them in practical arms control arrangements stemmed from a lack of interest and imagination, as well as from taking cooperative relations for granted. This left a “nuclear time bomb” under the foundation of Russian-U.S. relations, which quickly came to the surface and generated fresh, hostile nuclear interactions when domestic and foreign political factors drove Russia and the West apart in 2013.

A 2006 initiative by four prominent American statesmen to revive the idea of a nuclear-free world as a final goal of nuclear arms control was met with a broad positive response in the world’s political and expert communities.[vi] This quest was reciprocated by analogous groups of public figures in many countries, including Russia.[vii] The initiative was crucial in propelling the Obama administration’s policy on the issue, and it facilitated New START in 2010, as well as a number of important projects on the safety of nuclear materials in the world. Nonetheless, as an isolated attempt to enhance nuclear security, it met with growing political and strategic obstacles after 2011.

The tension between the polycentric world order and nuclear disarmament was clearly manifested by the failure of a multilateral arms limitation regime to materialize. Third countries have participated in treaties that restrict manufacturing and qualitative developments in weaponry (the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, NPT, and CTBT) as well as disarmament agreements that apply to certain spaces (such as treaties banning the stationing of weapons of mass destruction in outer space, on the seabed, and on the ocean floor, and accords involving nuclear-weapon-free zones). However, third nuclear-weapon states have not agreed to legally binding nuclear-weapon limitations, despite both deep reductions in Russian and American nuclear arsenals since 1991 and Moscow’s appeals to make the bilateral process a multilateral one (which have occasionally been supported by Washington).

There have not been any well-thought-out proposals for an effective way in which these states could join the disarmament process. In fact, it is not even clear which conceptual framework—parity, proportionate reductions, or strategic stability, among many others—should be adopted for multilateral limitations. There is also neither any accepted definition of the kinds and types of nuclear weapons that could be subject to agreements, nor any serious elaboration of acceptable and sufficient verification mechanisms.

As for the third countries themselves, they continue to assert that Russia and the United States still possess 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons and call for the “Big Two” to undertake reductions to levels close to their own as a precondition for participating in the multilateral disarmament process. This would imply yet another order-of-magnitude reduction for the two leading powers after cuts of almost the same scale since 1991, which hardly seems realistic.

After the end of the Cold War, nuclear nonproliferation replaced nuclear disarmament as the central security issue for the new world order. In turn, disarmament now plays a more or less subordinate role in helping to strengthen the NPT regime and institutions (as per Article VI of the treaty). Nevertheless, states, politicians, and experts around the world have endlessly disagreed on whether there is a correlation between additional disarmament measures and further steps to enhance the nonproliferation regime.

Another important new problem was that although Russia and the United States retained their leading roles in the nonproliferation regime, they could no longer dictate terms to other countries, not least because they disagreed on various political and economic issues. The history of negotiations on the North Korean and Iranian nuclear programs provides telling examples of the limited capabilities of the two leading powers and the entire P5 group, along with its major allies (Germany, Japan, and South Korea).

Furthermore, the United States and Russia have maintained partnerships with some countries of proliferation concern (India, Iran, and Pakistan). They have also competed against each other as exporters of peaceful nuclear technologies and materials. The non-nuclear NPT members resent the privileged position of the treaty’s “Nuclear Five” and have been especially critical of Russia and the United States.

In stark contrast to the situation during the Cold War, the great powers are no longer willing to take as much responsibility, bear as many costs, or accept as many losses as they did to ensure the security of their partners and clients. At the same time, the great powers have resorted to force many times in the last quarter century—in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the post-Soviet space. As a result, some nonaligned countries have turned to their own resources to ensure their security and status, and they see the acquisition of nuclear energy assets and their inherent technological potential for creating nuclear weapons as an appealing option. After the outstanding achievements of the early and mid-1990s, all these factors have created growing obstacles to strengthening the nuclear nonproliferation regime.

The development of new methods of arms control at this time was consistent with the emerging post-Cold War world order. They included strengthening the NPT regime and enhancing International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards; developing stricter control over storage facilities for nuclear weapons and fissile materials; increasing security at nuclear sites; and stopping the production of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. Other methods have included returning highly-enriched uranium fuel for research reactors to the exporter countries and modifying the reactors to use low-enriched uranium, as well as creating nuclear fuel banks to ensure the nonproliferation of national nuclear fuel cycle technologies.

These new forms of nuclear arms control could, however, only be developed in conjunction with concurrent nuclear arms reductions by Russia and the United States, and—eventually—other nuclear-weapon states. However, starting in the late 1990s, Russian-American negotiations began to slow down and then came to a complete standstill after the 2010 New START.

Two major political obstacles to nuclear arms control had emerged at the start of the second decade of the new century. First, problems other than nuclear arms control dominated the security agenda of the polycentric world. Second, the renewed confrontation and curtailed cooperation between Russia and the United States had undermined the political momentum that facilitated negotiations and agreements in the 1990s and during the brief reset period of 2009 to 2011.

Many politicians and experts (especially in Russia) have recently brushed off mutual nuclear reductions as a Cold War relic that has no significance in the modern world. Their bravado notwithstanding, the deep stagnation of this process is fraught with dire consequences.

To read the entire paper, please click external pagehere.call_made

[i] Bob Corker, United States Senator, “Russian Aggression Prevention Act text, Section by Section Overview,” external pagehttp://www.corker.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/9fb69acf-ec5a-4398-9721-66321a9e14cd/Section%20by%20Section%20-%20Russian%20Aggression%20Prevention%20Act%20-%20043014.pdfcall_made; Steven Starr, “‘The Russian Aggression Prevention Act’ (RAPA): A Direct Path to Nuclear War with Russia,” Global Research, August 22, 2014, external pagehttp://www.globalresearch.ca/the-russian-aggression-prevention-act-rapa-a-direct-path-to-nuclear-war-with-russia/539717call_made; Vladimir Ivanov, “Amerike ne nuzhen moshchnyy ‘yadernyy zabor’” [America Does Not Need a Thick “Nuclear Wall”], Nezavisimaya Gazeta, December 19, 2014, external pagehttp://nvo.ng.ru/realty/2014-12-19/10_nuclear.html?auth_service_error=1&id_user=Ycall_made.

[ii] Zasedanie mezhdunarodnogo diskussionnogo kluba ‘Valdai’” [Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club], September 19, 2013, external pagehttp://news.kremlin.ru/news/19243call_made, accessed on January 19, 2015; “Dogovor po RSMD ne mozhet deystvovat’ beskonechno, zayavil Ivanov” [INF Treaty Can’t Last Forever, Ivanov Said], RIA Novosti, June 21, 2013, external pagehttp://ria.ru/defense_safety/20130621/945019919.htmlcall_made.

[iii] Sergei Brezkun, “Dogovory dolzhny soblyudat’sya, no—lish’ s dobrosovestnym partnerom”[Pacta Sunt Servanda, But with Responsible Partners Only],Nezavisimaya Gazeta, August 22, 2014, external pagehttp://nvo.ng.ru/concepts/2014-08-22/4_dogovor.htmlcall_made.

[iv] Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club, October 24, 2014, external pagehttp://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/46860call_made.

[v] For instance, the United States once proposed that only strategic submarines currently at sea, but not at their bases, be counted along with their intercontinental ballistic missiles under the agreed upon ceilings of 2,000–2,200 nuclear weapons.

[vi] George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and Sam Nunn, “Toward a Nuclear Free World,” Washington Post, January 15, 2008, external pagehttp://www.wsj.com/articles/SB120036422673589947call_made.

[vii] Yevgeny Primakov, Igor Ivanov, Yevgeny Velikhov, and Mikhail Moiseev, “Moving from Nuclear Deterrence to Mutual Security,” Izvestia Daily, October 14, 2010, external pagehttp://www.abolitionforum.org/site/moving-from-nuclear-deterrence-to-mutual-security/call_made.