Back to Basics or Just Backwards? An Agenda for NATO's 2016 Warsaw Summit

16 Sep 2015

By Trine Flockhart for Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)

This Policy Brief was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageDanish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)call_made on 1 September 2015.

NATO should be careful not to let the ‘back to basics’ rhetoric steal the show at the 2016 Warsaw Summit. By moving away from out-of-area operations with a crisis management focus back to its original purpose – collective defence – NATO will become irrelevant in the long run.

The problem is that going ‘back to basics’ sounds like an intentional limitation of NATO’s role in the 21st century, and it implies a downgrading of NATO’s two other core tasks: cooperative security and crisis management. The three core tasks were identified in the 2010 Strategic Concept as essential if the Alliance was to remain fit for the 21st century. Having multiple roles has served the Alliance well in the past. Moreover, important as the changes in the relationship with Russia are, the changes in the global strategic environment, which led NATO to codify its three core tasks in the first place, are still in play.

”Today we do not have the luxury to choose between collective defence and crisis management. For the first time in NATO’s history we have to do both”.

– NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, March 2015

A flexible and adaptable Alliance

The Alliance is – and always was – more than ‘just’ a defence alliance. This is clearly stated in the Washington Treaty, which emphasizes both ‘collective defence’ (Article Five) and ‘cooperative security’ (Article Two). Moreover, following the end of the Cold War, the Alliance added the role of crisis management through a growing practice of meeting security challenges outside NATO’s own geographical area. Had NATO been ‘just’ a defence alliance, ‘just’ doing territorial defence, it would have had no raison d’etre and would probably have disappeared along with the Cold War.

It was recently pointed out by NATO’s Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg, that one of NATO’s greatest strengths is its ability to adapt in response to changes in its strategic environment. The ability to do so stems directly from the Alliance standing on three legs rather than just one. During the Cold War, NATO focused almost exclusively on collective defence, whereas the post-Cold War period has been characterized by a focus on cooperative security through NATO’s growing circle of partnerships and increasingly – though at times reluctantly – on crisis management through NATO’s many operations.

In response to the dramatic deterioration in the relationship with Russia, the temptation is to go ‘back to basics’ to focus primarily, or even exclusively, on collective defence. Such a move would make sense if the Alliance was going back to a strategic environment similar to that of the Cold War. That, however, would not be an accurate reading of the emerging global security environment.

The nature of change in the security environment

It is tempting to think that the changes NATO has to respond to are ‘simply’ the return of a specific Russian threat and the emergence of a number of unruly non-state actors such as Islamic State. But what if Russia’s new assertiveness and the rise of IS are symptoms of even greater change? What if it is the basic structure of the international system that is changing; a change that is as significant – perhaps even more so – as the changes following the end of the Cold War?

There is no doubt that the international system is changing and that the rules-based liberal order established in the wake of the Second World War is being challenged and is under internal strain. A polycentric system appears to be emerging characterized by plurality of power and principle and by changing practices (such as hybrid war) and the weakening of its multilateral institutions as well as the emergence of new ones (such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank).

As new powers are rising, they challenge the understanding of how order in the international system should be maintained, and some are balancing against the Western powers (in Europe on NATO’s borders – in Asia more directed against the United States). In addition, the demise of the Arab Spring and the failure of Western efforts to bring democracy and stability to Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya wiped some of the shine off the liberal democratic model’s promise of freedom and prosperity.

The point is that these are changes that require more effort by engaging fully in all three core tasks rather than scaling back to just one of them.

A relevant NATO in a changed world

In the past NATO has had the luxury of being able to focus on just one or two of its core tasks. In the emerging security environment, however, the dilemma is that the challenges on NATO’s eastern and southern flanks seem to suggest that the Alliance should hurry ‘back to basics’ by shifting its focus to collective defence. Yet, it would be naïve to assume that NATO can simply abandon its commitment to crisis management at a time where there has never been more need for meeting security challenges in an increasingly unstable neighborhood.

‘Going back to basics’ ignores that in the new global environment, the United States will continue to rebalance towards Asia, and that alternative visions for international order-making are emerging.

Although there is no expectation for NATO to follow the United States in its rebalance towards Asia, there can be no doubt that the United States (no matter who resides in the White House from 2017) will expect the Europeans to do more in their own neighborhood. Moreover, in an environment of loosening alignments, differing visions of order-making and declining magnetism of the liberal model, partnerships will be needed more than ever to forge essential links across dividing lines, albeit that they are likely to be more difficult to sustain.

The problem is that the ‘going back to basics’ narrative emphasises one aspect of the changing security environment, but neglects other important changes that require NATO to focus on cooperative security and crisis management. In the long run ‘going back to basics’ will make NATO irrelevant.

The Warsaw Summit should aim to insure a relevant NATO for the 21st century rather than a retrenching Alliance characterized by ‘going back to basics’. A relevant NATO is able to play a full role in all three core tasks;

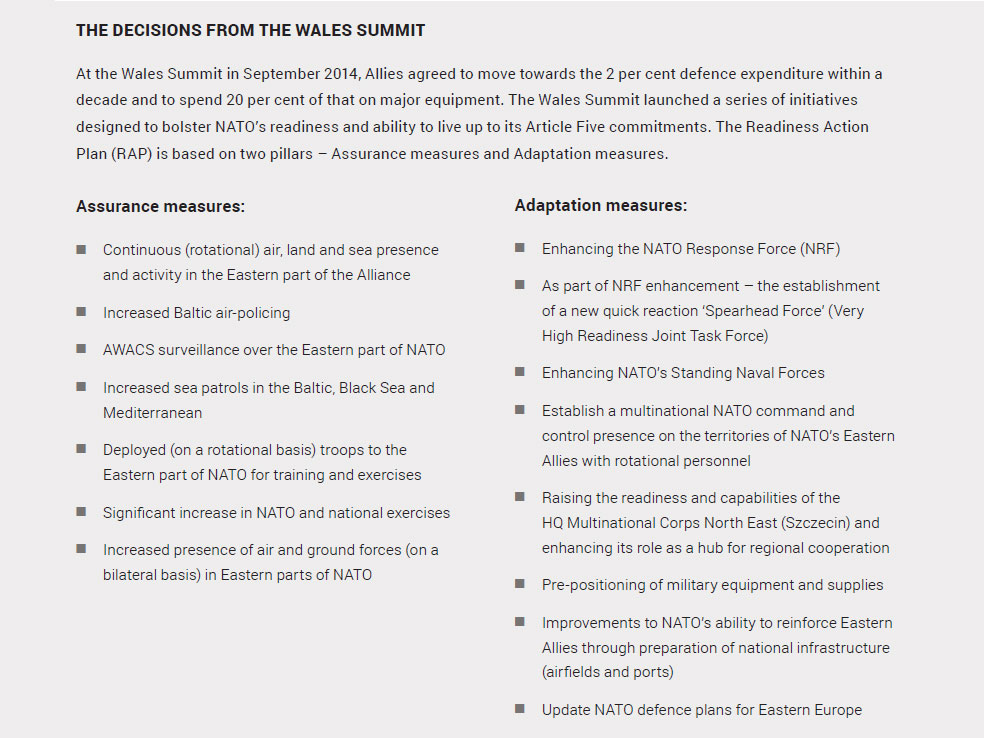

- in collective security – by fully implementing the decisions taken at the Wales Summit, including the 2 per cent spending pledge and the speedy and full implementation of the Readiness Action Plan (RAP).

- in cooperative security – by reassessing the role and function of NATO’s partnerships. Although partnerships can be based on shared values and eventually lead to membership, in the emerging strategic environment it is more likely they will be based on (perhaps narrow) shared interests and specific policy areas. Moreover partnerships with other international organizations, including the EU, are a pre-requisite for meeting many of the challenges in NATO’s own neighbourhood.

- in crisis management – by realizing that top-table credibility today comes from availability to contribute to crisis management operations rather than from having a static territorial defence. Agreement of, and participation in, crisis management operations is not an optional extra but is the foundation of a new implicit transatlantic bargain in which the ‘price’ for the continued relevance of the American security guarantee is an active contribution to order-making in the vicinity of Europe whilst the United States balances towards Asia. The improvements achieved through the RAP are equally relevant for crisis management as they are for collective defence.

Conclusion

Going ‘back to basics’, understood as an Alliance in which the United States guarantees Europe’s security in much the same way as it did during the Cold War, is absolutely not an option. To be sure, European NATO members need to implement the decisions taken at the Wales Summit to reassure its eastern allies and to reinforce its readiness and collective defence capabilities, but readiness and internal reassurance cannot come at the expense of NATO’s two other core tasks. National positions on how to proceed span a wide spectrum in NATO and not all support the rebalance from crisis management to collective defence. Even so the ‘back to basics’ narrative is damaging because it is pervasive and it implies otherwise.

The Polish hosts for the 2016 Warsaw Summit and NATO’s international staff should be mindful of the damage such a narrative can do to the long-term health of the Alliance. Having taken the decisions at Wales to increase readiness and reassurance (and swift implementation) is a positive first step towards a more healthy Alliance – next step is a new division of labour and a narrative of a more equal transatlantic partnership.