Syrian Medical NGOs in the Crisis: Realities, Perspectives and Challenges

30 Oct 2015

By Zedoun Alzoubi for Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre (NOREF)

This article wasexternal pageoriginallycall_madeexternal pagecall_madepublished byexternal pageNOREFcall_madeexternal pagecall_madeon 1 October 2015.

Introduction

Syrian civil society organisations (CSOs) were literally born during the current crisis in the country. Although, some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were established before the crisis, they were under the control of the Syrian government. Before the crisis Syrians rarely used the term “civil society” and considered it a Western way of culturally invading the country. The government always preferred the term “community-based organisations”, interfered in the appointment of their boards, controlled their operations and in some way owned these organisations. This did not prevent the existence of some NGOs, like Syria Trust, that were established and managed by the first lady, yet an NGO sector could nonetheless still not be considered to exist in its generally accepted form before the crisis.

After the crisis began many activists started to create various forms of NGOs in reaction to a range of issues. Firstly, the severity of the violence inflicted by government forces in the first six months of the crisis required some kind of action to document human rights violations, which was undertaken by CSOs such as the Syria Violations Documentation Centre. Also, violence and the insecurity of public hospitals made many doctors opt to start NGOs to tackle issues related to treating people who were wounded in demonstrations. Secondly, many pacifists found themselves sidelined after the transformation of the civil movement into an armed one, especially after the second half of 2012. This led many such pacifists to establish humanitarian and developmental NGOs to compensate for the role they had lost in the uprising. Thirdly, after the last quarter of 2012 many parts of Syria gradually slipped beyond government control and hence there was a need for some kind of action to deliver services in these areas. The opposition failed to establish a body that could fill the vacuum that resulted from the withdrawal of Syrian government agencies, so consequently there was a need for CSOs to step in.

These newly born CSOs faced several challenges. Firstly, most were quite immature and had little organisational experience. They lacked professional training, including essential expertise in finance, human resources, supply chain management, etc. Secondly, they faced legal constraints, because they could not register in Syria. Instead they had to register in Europe, the U.S., Canada or neighbouring countries, which required knowledge of these countries’ legal frameworks. Financial transactions, including simple money transfers, were particularly difficult, due to the sanctions imposed on Syria. This forced many organisations to change their names and remove the word “Syria” from their titles. Thirdly,these organisations had little knowledge of the role and nature of civil society, and the importance of remaining non-partisan.1 Many had very strong political terminology in their mission statements that contradicted the essential nature of civil society. This at times led many of these organisations to play a harmful political role. For example, the Syrian Journalists Association had the aim of “toppling the regime” as one of its objectives, and when its management tried to remove this term from its bylaws, many members protested and withdrew from the association. Fourthly,these organisations had to face an extremely difficult security environment that involved dealing with several extremist groups on both sides. Many organisations failed to negotiate access and service provision terms with these groups, while others lost staff in the ongoing fighting.

Medical organisations are no exception to these trends; rather, they are situated at the heart of the crisis. In this expert analysis we will discuss the challenges faced by these organisations, their perceptions, and the recommendations related to them made by the decision-makers in these organisations and in donor circles. Although most of the discussion will revolve around Syrian NGOs in opposition-controlled areas, because they form the vast majority of the country’s NGOs, the findings of this expert analysis apply to a large extent to Syrian NGOs in government-controlled areas.

Most of what is stated in the discussion comes from the author’s direct observations, which means that it reflects the point of view of the author, who manages a Syrian-led medical organisation, the International Union of Health Care and Medical Relief Organisations (UOSSM). This means that the major biases in the article stem from two main sources. Firstly, the author draws on his own experience gained from his organisation and partner organisations in opposition-controlled areas, and, secondly, the analysis mainly covers the challenges faced by Syrian medical NGOs in opposition-controlled areas and does not claim to deeply understand the problems faced by similar NGOs in government-controlled areas. For example, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) does an excellent job in government-controlled areas, but it is impossible to properly analyse the challenges it faces there.

Another challenge in writing this analysis is to understand what exactly a Syrian medical NGO is in the first place. Currently the major “Syrian” health service providers are the UOSSM, the Syrian American Medical Society, the Syrian Expatriates Medical Association, Shafaq, and, of course, the SARC. With the exception of the SARC, these organisations are not registered in Syria, and hence legally they belong to the country of their registration. On the other hand, Physicians Across Continents (PAC) (Turkey) is considered a Syrian organisation because it is largely dominated by Syrian nationals and has joined the Syrian NGO Alliance. Also, health directorates in opposition-controlled areas act very much like NGOs. There is no supervising authority to which they have to report, and they apply for funding directly to donors, very much like an NGO. For ease of analysis, this article considers Syrian medical NGOs to be those who are led by Syrians, operate inside Syria only (i.e. excluding PAC) and define themselves as NGOs (i.e. excluding health directorates).

Syrian medical organisations are “at the heart of the crisis”

From March 2011 it became clear that the main humanitarian challenge in Syria lay in health and protection. Although the Syrian humanitarian crisis is considered one of the most challenging since the Second World War, has affected almost every family in Syria and has required immense international intervention in all aspects of humanitarian response, it is clear that the health sector is one of the most affected sectors in the country.

The Syrian Center for Policy Research has documented that more than 90 health facilities were damaged by the end of 2013 alone (Syrian Center for Policy Research , 2014). While this expert analysis was being written (July 2015) more than 50 health facilities in the southern and northern regions of the country were targeted by the Syrian air force, while, for example, Islamic State (IS) forces killed the manager of Soran hospital. According to a report published in May 2015 by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR),

At least 610 medical personnel have been killed, and there have been 233 deliberate or indiscriminate attacks on 183 medical facilities. The Syrian government is responsible for 88 percent of the recorded hospital attacks and 97 percent of medical personnel killings, with 139 deaths directly attributed to torture or execution.

Attacks on healthcare facilities in Syria have reached their highest levels in a single month since the start of the conflict in March 2011. In May 2015 alone PHR documented 15 attacks on 14 medical facilities, including seven that had been previously attacked. Also, PHR documented the killing of ten medical personnel during the same month. It has found that government forces were responsible for “all of the May facility attacks and seven of the 10 personnel deaths” (Physicians for Human Rights, 2015).

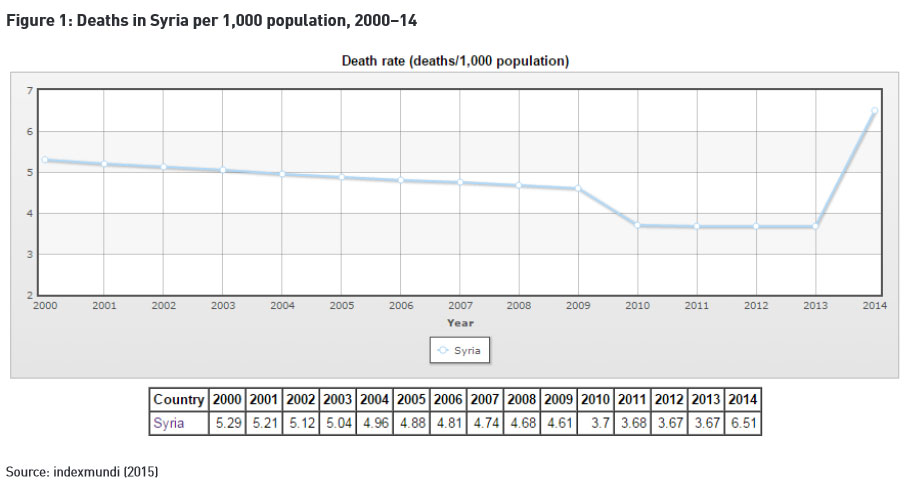

It has become evident that the areas controlled by the opposition and/or IS are suffering from a total failure of the healthcare system. This is characterised by high mortality rates, widespread epidemics and high levels of patient transfers to neighbouring countries (see Figure 1).

It is clear from Figure 1 that the increase in the death rate cannot be attributed only to direct war casualties, but also to the collapse of the health system in Syria. The absence of a central healthcare authority (whether opposition or government) that is able to carry out the required functions to maintain the healthcare system has pushed Syrian medical NGOs to fill this significant gap. In this effort they were faced with several challenges that can be categorised as follows:

•Organisational issues: These are issues related to the internal capacity of Syrian medical NGOs to conduct their operations.

•Inter-organisational issues: These are issues related to the relationships among various Syrian medical NGOs and organisations operating in opposition-controlled or government-controlled areas.

•Extra-organisational issues: These are issues related to relationships with the international community, including international NGOs (INGOs), United Nations (UN) agencies and governments. They are also related to relationships with military and civil forces inside Syria.

We will discuss these challenges in further detail below.

Organisational issues

As mentioned in the introduction, Syrian medical NGOs are very young to the NGO sector and have little of the kind of professional experience that is required by any organisation, irrespective of the context in which it operates. This is a legacy of the semi-social, state-controlled economy of the Ba’th Party government since 1963.

Most of these NGOs started as grassroots organisations characterised by direct board management, weak soft and hard skills, deep personal dedication and neutrality challenges, scarcity of resources, full dependence on donors, and, above all, a lack of knowledge of the specificities of civil society, i.e. adherence to the definition of what constitutes a proper NGO. In addition to these internal problems, logistical and security issues remain very clear obstacles in the attempts of Syrian NGOs to effectively and efficiently execute their projects. These challenges include the following:

•Board management: Newly formed organisations are usually managed directly by their boards of directors. However, when the board continues to be involved in the direct management of the organisation, management and implementation teams face issues with regard to the need for timely decision-making, which for the most part is still under the discretion of the board. Board members are volunteers, usually busy doctors, mostly located in the Gulf, Europe and North America, and therefore cannot manage these organisations effectively. Also, most board members lack or have little management experience, and there is poor communication among board members. This, of course, affects the implementation of projects on the ground. Very few organisations have moved towards having executive directors who are able to understand the organisations’ requirements, are close to the ground, and have the power to make decisions in a timely and effective way.

•Weak soft skills: Most Syrian medical NGOs – like Syrian NGOs in other sectors – have little knowledge of or skills and competencies in team building, networking, communications, time management, presentation, reporting and leadership. Moreover, most staff lack sound English language skills (because English is the main language of donors, Syrian NGOs need to write reports and proposals and discuss their work with donors using English – both general and technical English; they also need computer skills, mainly MS Access and Excel). Many management and implementation staff also lack specific soft skills that are crucial in a crisis-affected context, i.e. negotiation and conflict resolution skills. Although it is gradually improving, professional reporting remains an essential problem among these organisations. More importantly, most Syrian NGOs do not value the real need for such soft skills in their work and consider them as complementary skills to have during times of conflict. However, some Syrian NGOs are becoming more aware of the importance of such skills and are asking the donor community to focus more on capacity-building among Syrian organisations, but there is still much to be done in this regard.

•Weak hard skills: Hard skills, such as supply chain management, hospital management, programme management, and advanced medical services management and provision are extensively lacking. Most staff come from a particular political background – i.e. revolutionary in opposition areas and loyalist in government-controlled areas – rather than from a professional one. Until now, in many organisations, hiring policies depend on political affiliation rather than professional background, which means that many qualified staff are excluded from the workforce at various Syrian NGOs.

•Neutrality and passion challenges: Most of the staff who established or are employed by Syrian medical NGOs that function in opposition-controlled areas came from an opposition, revolutionary background that characterises their views of humanitarian work. Similarly, those who operate in government-controlled areas are from a “loyalist” background. This poses major challenges in communicating with donors and other Syrian CSOs, and in understanding their role as humanitarian organisations. Terms like “neutrality”, “objectivity” and “unbiased service provision” are not really embraced or understood by most organisations, and many see humanitarian action as political. Although many Syrian medical NGOs have changed their mission statements and logos to reflect neutrality in their activities, such “neutrality” still needs to be fully reflected in their behaviour and programmes. For example, the SARC does not really cooperate with Syrian medical NGOs operating in opposition areas. In fact, neither seems to be ready yet to be truly neutral and non-partisan. Also, the majority of the staff of these organisations are very emotionally involved in the crisis, making it very difficult for them to take decisions according to guidelines based on fulfilling the needs and providing for the general safety of those they deal with. However, many medical workers are willing to take high risks in their humanitarian activities.

•Donor dependency and financial issues: Syrian medical NGOs started their operations in the first year of the crisis by mainly depending on donations from individual Syrians – mainly doctors in the diaspora. From the second year of the crisis these organisations started to establish relations with government-related agencies and INGOs. This has not changed much since then and these organisations have not established their own fund-yielding projects or self-generated revenues. They still rely very much on two types of funding. The first – and largest – is public funding from international institutions and partners, including multilateral and bilateral donors, as well as INGOs. The second type of income is private funding, which is still small in scale and poorly designed, whether in terms of fundraising events that mainly target Syrian communities abroad or establishing relations with private foundations or donors. Very few organisations have established relations with businesses or profit-oriented projects. Moreover, there is still little knowledge of how to undertake online fundraising and make use of social media. Syrian medical NGOs not only rely on international donors, but many do not know how to establish professional relations with such donors. Very few organisations carry out donor mapping or donor analysis, or have concrete donor relationship strategies. In addition to these challenges the sanctions on Syria have been negatively affecting these organisations. Most bank transfers take weeks, if not months. If the organisation has the word “Syria” in its title it might be subject to many legal and administrative hurdles. This means that many organisations have had to change their names and even their mission statements to avoid such difficulties.

•Logistical and security challenges: The Syrian conflict is very complex and the level of violence is extremely high. Syrian medical NGOs are at the front lines of this violence and face the systematic destructive targeting of both medical facilities and medical personnel. Moreover, organisations that work in opposition-controlled areas have to deal with various civil and military powers with different ideologies and agendas. Negotiation skills are extremely important in such contexts. Furthermore, operating in IS-controlled areas poses a special challenge for many reasons. Firstly, the behaviour of this group is in many instances unpredictable and might change from one day to the next and from one area to another. To a large extent decisions in IS-controlled territories are made by the “amir” in charge of the region, who could change his mind for no clear reasons, posing risks to working staff and organisations. This has forced most organisations to leave these areas, with only a handful remaining. Also, working in these areas requires Syrian medical NGOs to establish a relationship with local medical organisations and commissions that act as mediators between the NGOs and IS. Working with these mediators requires high levels of negotiation skills and tools for verification and validation that still need to be improved by most NGOs. On the other hand, opposition-controlled areas that are dominated by Jabhat al-Nusra (JAN) and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) are characterised by different contexts and require different negotiation skills. Most of these forces have not deeply interfered in the operations of Syrian medical NGOs. Despite that, some incidents show that this behaviour is not stable and might change drastically in the future, which requires these NGOs to be prepared for all possible scenarios. At the moment strategic, long-term planning seems a luxury. Moreover, relationships with local administration councils (LACs) are not yet fully established, for many reasons. Firstly, LACs suffer from many problems, including those of governance and financial support. Secondly, the LACs’ role is mostly still only vaguely defined. Until now most LACs have operated very much like CSOs: they have neither a government to report to, mechanisms to mobilise resources in their areas, a clear budget nor representational legitimacy. Most of them write proposals to donors and are not democratically elected, which makes them just like any CSO that is competing with other CSOs. This issue will be further addressed below.

Inter-organisational issues

Inter-organisational challenges are the challenges facing Syrian medical NGOs in dealing with other institutions or organisations. These challenges include, but are not limited to, other Syrian medical NGOs, civic and military forces in Syria, international institutions, and the international donor community.

Due to the immaturity of the newly established Syrian civil society, most Syrian organisations encounter difficulties in dealing with one another. Until now this interrelationship has been characterised by competition and distrust. However, this has moved through various stages and gradually seems to be improving over time. The first stage was apparent as early as 2012, when many organisations rushed to create unions and coalitions under the pressure of the crisis. However, this process was poorly handled. There was no clear vision on how to structure such collaborations without compromising the identity of the organisations involved. Hence, many of these unions and coalitions fully or partially failed. This was followed by a period until 2014 characterised by competition and mistrust. By the end of 2014 many organisations started to value cooperation and gained more experience of how coalitions might be developed. Accordingly, many unions and coalitions came into existence with various roles. The most famous coalitions are as follows:

•The Syrian Civil Society Coalition mainly focuses on peacebuilding.

•The Syrian NGOs’ Alliance and Syria Relief Network focus on advocacy for humanitarian operations.

•The Syrian Hope Alliance for Modernity and Liberty focuses on the co-implementation of projects and complementarity among Syrian NGOs.

•The Union of Syrian Civil Society Organisations focuses on capacity-building.

The emergence of these networks, although promising, does not rule out the mistrust that exists among Syrian NGOs, and medical NGOs are no exception. This mistrust exists for several reasons. Firstly, most of these organisations have some kind of political agenda, which affects the relationship among them, which in turn translates into difficulties in overcoming political dissimilarities. Secondly, the scarcity of resources drives these organisations to compete for all types of resources, mainly of the human and financial kind. Thirdly, many donors follow an approach that focuses only on one major partner, which forces medical NGOs to compete for donors.

Although some donors have started to focus on multilateral projects that involve two or more Syrian NGOs, this is still uncommon. Currently there are very few examples of real information-sharing platforms that allow for greater efficiency and effectiveness in the health sector, despite the Health Working Group, facilitated by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). For example, the first round of the UNOCHA-administered Humanitarian Pool Fund witnessed a business-like call for bids, where medical organisations presented their proposals secretly, which prevented better coordination and planning of the already limited existing fund.

Extra-organisational issues

Relationship with the international donor community

Although the relationship between Syrian medical NGOs and the international donor community has gradually improved over the past two years, it still suffers a great deal of mutual misunderstanding. Firstly, many donors have little knowledge of the Syrian context. Many of them do not understand the limits of Syrian NGOs, on the one hand, and the complexities of the Syrian context, on the other hand. Some INGOs fail to understand that there is no government in more than half the country, and thus often ask Syrian NGOs to do the impossible.2

Moreover, many Syrian NGOs criticise some INGOs for deciding on the projects they want to fund rather than tailoring the projects to the needs of the people inside Syria. Some Syrian NGOs also complain about INGOs that want to impose their own system, disregarding the capacity of Syrian NGOs and their own established systems. For example, most donors distance themselves from trauma projects (field hospitals), especially in the north-east regions of Syria, i.e. in IS-controlled areas. These areas suffer from a severe shortage of health services, because most donors will not support projects in these areas, although they contain more than 2.5 million people. Besieged areas also receive little support from donors, because donors’ documentation requirements cannot be met in these areas. Another major issue is that many Syrian medical NGOs feel that there is competition with INGOs instead of cooperation, especially over human resources. Many INGOs offer salaries that most of Syrian medical NGOs cannot match, which creates a huge problem, considering the high emigration rate for doctors.3

On a different note, training of the sort that is needed by most Syrian NGOs, especially medical NGOs, such as supply chain management, negotiation skills, dealing with counter-terrorism legislations, etc., is overlooked by most donors. Very few donors are willing to support projects that focus only on the training and capacity-building of the organisations they support, and would rather integrate this training into their actual projects on a limited scale, which is usually not sufficient.

On the other hand, INGOs experience problems with Syrian NGOs, many of which are hotbeds of conspiracy theories and accuse some INGOs of being involved in conspiracies. This means that occasionally detailed data about projects is unavailable. Syrian NGOs accuse INGOs of hindering direct relationships between the former and large donors such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the British Department for International Development (DFID) and the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civilian Protection department (ECHO), saying that INGOs underestimate the capacity of Syrian NGOs to retain control of projects. Also, NGOs do not enforce basic humanitarian principles, as mentioned above. Moreover, the lack of professional conduct by Syrian NGOs in general creates a gap between the actual behaviour of these NGOs and the requirements of INGOs.

One major issue that it is worth mentioning is the reluctance of government-related agencies to provide direct funds to Syrian NGOs. So far, very few organisations – if any – receive funds directly from the DFID, USAID or ECHO. This underestimation of Syrian NGOs’ capacity has led to a feeling of a lack of mutual support between donors and beneficiaries. For the most part this can be attributed to the immaturity of the newly established Syrian NGOs in general, which is quite understandable. However, this issue has to be addressed strategically, in light of the fact that many Syrian NGOs, particularly medical NGOs, have drastically enhanced their strategic planning and operational capacity. Finally, it must be acknowledged that the gap between Syrian NGOs and INGOs, and the donor community is narrowing. However, a great deal still has to be done to create a more cooperative working environment.

Relationship with community-based organisations and LACs

LACs and local NGOs play a major role in the delivery of services. Firstly, they have better knowledge of the requirements of their respective areas. Secondly, they are in a better position to negotiate with military factions that control their areas. Local organisations play a major role in IS-controlled areas and are effectively the only mediator between Syrian NGOs and INGOs, on the one hand, and IS, on the other. There is little chance for any project to be successful without their involvement. Also, these organisations play a mediating role between the community and Syrian NGOs. In the same way that INGOs suffer when they work with Syrian NGOs, the latter also suffer when they deal with local NGOs and LACs, who are even more inadequate in terms of the required competencies. Also, there are material differences in capacity and legitimacy among LACs: some have developed their skills and relations with the community and military factions, while many are still lagging behind. This complicates the ability of Syrian NGOs to implement their projects. INGOs and Syrian NGOs should cooperate to provide training that address the needs of local organisations and LACs. The lack of skills among LACs and local NGOs results in very complicated relationships. Some Syrian NGOs and INGOs opted to give local organisations full control over projects, which resulted in their complete failure, with some exceptions, such as Tamkeen (see the following paragraph).4 Others decided to fully marginalise local organisations, which will only hamper development in the long run.

One good example of the kind of action that is needed is Tamkeen, which is funded by the DFID. Through extensive consultations Tamkeen creates a consortium of Syrian NGOs, LACs and local NGOs to decide on projects. They all receive training tailored to the needed skills and the project is supported by international partners to improve effectiveness and efficiency. Unfortunately, Syrian medical NGOs have not yet started such initiatives.

Relationship with military factions

This is the most complicated relationship faced by NGOs and could be the most influential, especially for Syrian medical NGOs, because the operations of the latter directly affect the militias. This relationship has never achieved a state either of full confrontation or cooperation, but is more one of mutual interest. Syrian NGOs in general, and Syrian medical NGOs in particular, are needed by all militias, while these NGOs cannot work without the consent of the militias. Most militias – if not all of them – need the medical services provided by Syrian medical NGOs either to their wounded fighters or to the communities they claim to protect. This has both a positive and negative impact. The positive impact comes from the authority that Syrian medical NGOs have over these militias, making the latter in many cases abide by NGOs’ conditions. The negative impact is that in many cases health facilities are pressured by militias to provide preferential treatment for their fighters. Militias have frequently attacked doctors and health facilities after accusing them of providing inadequate or improper treatment. In other cases some groups have prevented medical assistance being given to communities living under the control of other groups.5 However, there are differences in how militias deal with Syrian medical NGOs.

The FSA and Kurdish forces interfere the least in the operations of Syrian medical NGOs, while Kurdish forces show more disciplined behaviour than FSA fighters. JAN tends not to interfere in the operations of Syrian medical NGOs, but has tried at least once to control the warehouses containing medical supplies under the pretext of unifying humanitarian aid. JAN seems more strategic in dealing with humanitarian aid and general civil work in areas under its control. Although there is no concrete evidence, some accidents do give the impression that JAN is still waiting for the right moment to control all civil work in its territories. This will be a major challenge that Syrian medical NGOs will need to consider strategically.

The most difficult militia to deal with is IS, which directly interferes with the work of Syrian medical NGOs, including trying to control their operations, hiring and firing processes, and financial transactions. Of course, these NGOs do not allow IS to appoint staff and control financial transactions, not only because this would undermine their operational standards, but also due to their fears of legal consequences. This has led to a confrontation between the two sides. Lately, IS has banned the operations of most Syrian medical NGOs, accusing them of being collaborators with the West and of being Christian missionaries. Some staff members have been kidnapped and tortured. However, there seems to be no general standards for how IS deals with Syrian medical NGOs. What happens in eastern Aleppo is different from what happens in Raqqa or Der’Azor, for example. Although it is quite difficult to understand how IS policies are made, it is widely believed that the amir in charge of a particular area decides what is acceptable or not. Also, IS seems to be the only militia that does not care much about the communities it governs. This is why IS is more flexible when dealing with medical organisations that only provide trauma services, which can assist its fighters, than those who provide primary health-care services to the general population, mainly to women and children.

Dealing with IS is the most difficult challenge facing Syrian medical NGOs and requires patience, negotiation skills and intelligence. So far these NGOs have been able to reach some compromises with IS, e.g. when they stood firm in preventing IS from controlling their operations and when they decided to cease operations if IS interfered, but this has led to depriving people of access to medical services, making enormous health crises possible in the near future, including polio, tuberculosis and water-borne diseases. Although some local NGOs are trying to mediate and help in allowing medical organisations to operate in IS-controlled territory once more, it seems that there is no real solution to this dilemma at this stage.

Relationship with the governments of neighbouring countries

There was a noticeable difference in the scope of operations of Syrian medical NGOs after the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2165 (2014), which allowed for cross-border operations. Part of the essential work of these NGOs is to deal with the governments of neighbouring countries – Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon – especially after UN Resolution 2165. Operations from Iraqi Kurdistan areas are still very limited and hence there is little interaction with the Kurdistan government.

NGOs’ relationship with the Turkish government is still the easiest, despite the closure of the border in early 2015. The Turkish government allows medical supplies, doctors, and NGO personnel to cross the border from and to Syria, although this has become more difficult since the border closure due to the restrictions on movement imposed by the Turkish government.

The Jordanian government controls its borders strictly to prevent the infiltration of foreign fighters and to limit the number of refugees. These control measures have been strictly imposed on NGOs too. It is extremely difficult for doctors to cross to the Jordanian side of the border to receive medical training and visit their families, or to allow medical trainers to enter Syria. This has a negative impact on the ability to respond to the increasing risk of losing skilled doctors in the south. Nevertheless, the Jordanian government does allow daily shipments of medical supplies to enter southern Syria.

Many claim that the Lebanese government is not as cooperative as it should be.6 All Syrian medical NGOs risk having their staff arrested or deported, and there is no way to use Security Council Resolution 2165 to allow for cross-border operations into Syria, which means that no medical supplies whatsoever enter Syria from Lebanon. This has an extremely negative effect on areas like the Damascus countryside and Homs.

It must be emphasised that the movement of doctors from and to Syria is crucial in maintaining health services inside the country. Many doctors leave to visit their families outside the country. If this is limited or prevented then an even worse disaster can be expected, with waves of refugees leaving the country because of lack of medical and healthcare services.

Perspectives and future role

It is obvious that the Syrian crisis will not end soon. Even if it does, Syrian medical NGOs will have to play a major role in restoring the country’s destroyed healthcare system. This puts huge responsibilities on these organisations that they are not ready for at the moment, as discussed above. In order to be prepared for their current and future role, they have to become aware of the requirements of such a role.

Firstly, they have to realise that passion and dedication are necessary in humanitarian work, but are not enough in themselves. Medical NGOs also need high levels of professional and sustainable development of their organisational capacity. These organisations must focus on training in terms of issues like monitoring and evaluation, financial management, quality management, relationship management, etc. in addition to skills that are particularly necessary in the Syrian context, including negotiation and conflict resolution skills.

Secondly, due to the very complex environment in which they operate, Syrian medical NGOs need to increase their knowledge of how to tackle challenges caused by international counter-terrorism legislation and measures. It is clear that medical assistance has a sensitive position because medical services might be perceived as supporting one or other militia. Neglecting this issue might result in very critical conditions for the organisations supplying medical assistance.

Thirdly – and possibly most importantly – these organisations have to move from crisis response to strategic planning that focuses on sustainable development. They have to draw up plans to decrease their dependence on donors and become more self-reliant through direct access to public funds by establishing for-profit organisations that finance NGOs and having their own service fee structures at the local level. The latter factor, i.e. collecting fees at the local level, is of a great importance, not only for the organisations concerned, but also for communities in Syria. It requires a careful strategic planning process that focuses on developing relationship with LACs and local communities. Obviously, LACs are not yet competent to handle such partnerships and initiatives. However, it is very important to develop long-term planning to transfer knowledge and legitimacy from NGOs to LACs in order to allow for the restoration of the public health sector. This would require gradual, slow partnership development. Syrian medical NGOs could start by partially delegating monitoring and evaluation functions to LACs and involve them in the management of healthcare facilities gradually and cautiously until a particular LAC is ready to exercise full authority over the relevant health facility. Of course, this strategy cannot be implemented without collective efforts by all Syrian NGOs to abandon competition among themselves and start creating coordination and collaboration networks and alliances.

Such a role will obviously not be played by Syrian NGOs without the full support of donors, whether governments or INGOs. INGOs must build better relations with Syrian NGOs and help to remove the sense of competition felt by the latter. The gradual transfer of projects, skills and expertise from INGOs to Syrian NGOs is essential to move from crisis response to development. INGOs and government need to support the co-implementation of projects to enhance cooperation among Syrians.

Finally, governments, INGOs and Syrian NGOs need to start projects that have a cross-line impact: if Syrian NGOs do not develop projects that involve beneficiaries on both sides of the conflict, the conflict will surly worsen. A dialogue between Syrian NGOs on both sides of the conflict therefore needs to start as soon as possible.