The Rise and Decline of the Caucasus Emirate

1 Aug 2016

By Grazvydas Jasutis for Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)

Key Points

- In October 2007, Dokka Umarov proclaimed the establishment of the Caucasus Emirate (CE), transforming the armed Chechen nationalist resistance into a jihadist movement with a limited pan-Caucasian identity.

- From 2013 to 2015, the CE underwent substantial changes that dramatically modified its character and its role in regional affairs. Umarov’s death in 2013 sped up the process of conversion and resulted in the decline of the CE.

- The organisation faced a real schism as a result of CE members joining the so-called Islamic State (IS). The pledge of the bayat (oath of allegiance) to IS by numerous CE field commanders demonstrates that IS will be playing a key role in controlling and financing the insurgency in North Caucasus. Nevertheless, IS will not fully take over armed resistance in the region.

- The CE may be considering appointing a new leader to revive its fortunes, re-establish links between the Chechen diaspora and jamaats (autonomous combat formations), and generate the income needed for the insurgency.

- The CE is likely searching for a new identity, which might rely on a mixture of pan-Caucasian and jihadist ideas, and which differs from IS. Even with a new leader and fresh ideas, the CE will remain a marginal insurgency, because its offensive capabilities are impaired and because local support for armed resistance is drastically reduced.

1 Introduction

On 23 June 2015, the spokesman of the Islamic State (IS), Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, declared the establishment of a new governate incorporating the territory of the Russian Federation from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea, the Vilayat Qawqaz. By doing so, IS attempted to extend the territory it controls, and in the process presumably swallow another terrorist organisation, the Caucasus Emirate (CE), which had been operating in the troubled area of North Caucasus. The CE was created in October 2007 by former Chechen field commander Dokka Umarov as a Salafist-Takfiri jihadist group. Since its inception it has claimed responsibility for hundreds of terrorist attacks in the Russian Federation, and has been considered to be the main threat to the stability and security of the region. Its ambiguous affiliation with IS has resulted in friction within the CE, as well as creating a series of complex issues that need to be addressed at both the practical and academic levels.

On 29 December 2015, Salim, the amir (head) of the United Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay vilayet (administrative division or entity), posted a statement on YouTube disclosing internal disagreements and problems within the organisation as a result of the integration of many of its forces into IS. It therefore remains unclear whether the CE will continue as part of a global jihadist group, enjoying various benefits from its association with IS, or whether it will identify itself regionally and take on a different character while operating with limited resources.

2 Origins of the Caucasus Emirates

Regional commentators and experts provide a wide range of explanations as to the origins of the CE. In October 2007, Dokka Umarov abandoned the idea of an independent Chechnya and announced the creation of the CE, which changed the region’s security situation both qualitatively and quantitatively. His declaration referred to eight essential issues: the Russian occupation; the establishment of sharia law; the armed opposition; links to Chechnya; the rejection of all Caucasus law; the establishment of the CE; the intention to wage war outside the Caucasus; and the declaration of himself as the sole leader of the CE. The text of the declaration hints at the origins of the CE and its objectives. However, there are different opinions and perceptions as to the origins of the organisation, which vary depending on sources, interlocutors, and cultural and religious contexts.

Primarily, it is important to note the role of the armed struggle for Chechen independence from the Russian Federation, because the creation of the CE follows on from this struggle. The declaration of the creation of the CE itself states that the jihad (holy war) against Russian kafirs (unbelievers) has never stopped and that it was revived 16 years ago in Chechnya when Dzhokhar Dudayev became the leader of the Chechen people. The CE’s founder, Dokka Umarov, had a mercurial personality and a background in business and criminal activities.

He joined the struggle for Chechen independence in 1994 when he was 30 years old. He was a field commander during the first Chechen war of independence, which must have had a social impact on his perception of the future of Chechnya. In the inter-war period, he was appointed head of the Chechen Security Council and he supported the Sufi community in their clash with the Salafists (such as in Gudermes in 1998). He did not support the radical wing that, under Shamil Basayev’s command, staged military operations in Dagestan, which led to the second Chechen war. He was later appointed as the commander of the south-western front and participated in armed resistance during the second Chechen war. In 2004, the president of the Chechen Republic-Ichkeria, Abdul Halim Sadulayev, appointed him as vice-president. He was automatically proclaimed president following Sadulayev’s death in 2006. Umarov was therefore closely related to the struggle for Chechnya’s independence, and the principle of statehood must have played a significant role in his perceptions and actions. His public statements, speeches and interviews strengthen the idea that Umarov was a pro-Chechen fighter with a clearly expressed Chechen identity, but this did not appear in the text of the CE declaration. Another explanation of the origins of the CE focuses on the expansion of global jihad under the label of Salafism, with potential input from al-Qaeda. The CE declaration places heavy emphasis on Salafism. Although this may not be particularly clearly expressed in the text itself, further explorations of Umarov’s statements and CE activities reveal evidence that supports the idea that the CE is based on Salafism and remains ideologically linked to al-Qaeda. Salafism contains four major elements that are reflected in the CE: tawhid (the ones of Allah); al wala’ wa’l bara (enmity towards non-Muslims); the rejection as blasphemy of shirk (polytheism); and bida’ (non-acceptance of innovations) in Islam such as worshipping Allah in ways not specified in the Quran and Sunnah. Experts agree that the CE has fully embraced the Salafist-Takfiri jihadist ideology: to liberate the Islamic Ummah from jahiliyyah (ignorance of divine guidance); to rid the world of murtad (apostasy) and kafirs (unbelievers); and to establish sharia law throughout the entire world1. This appears strange, because Umarov was committed to a nationalist approach and followed the Sufi Qadir tariqat (order).

The appearance of Salafism as the cornerstone of CE ideology can most likely be traced back to the ideas propagated by foreign fighters associated with al-Qaeda. For example, the notorious Saudi Arabian Umar ibn Khatab, a close ally of Shamil Basayev and a friend of Osama Bin Laden, operated in Chechnya and created the International Islamic Brigade, which consisted of foreign fighters and mercenaries. He advocated Salafism and required Salafist-appropriate behaviour and attitudes from his fellows and staff. A significant part of the insurgency in Chechnya and North Caucasus, together with its radical wing (that is, the CE), has never acknowledged this fact and denies any affiliation with al-Qaeda.

However, there was a large presence of foreign fighters with an al-Qaeda background who shared the ideas of Salafism. These facts, together with significant financial flows, tell a different story. Until 2004, Chechnya received approximately USD 20 million and an enormous amount of equipment through al-Qaeda channels (al-Qaeda material and financial support were organised through the Benevolence International Foundation, which operated in Grozny and Tbilisi).2 This support did not stop even after the deaths of Khatab and Basayev, indicating that Umarov became the recipient of these financial injections. It is obvious that al-Qaeda did not give operational orders in Chechnya (although it ran training camps in the area); however, the ideological links clearly indicate its close relations with the Chechen insurgency. Furthermore, al-Qaeda underwent a process of transformation over time, and newly created organisations under the ideological auspices of or affiliated with al-Qaeda rapidly reverted to their own modus operandi and ultimately made little or no reference to the mother organisation.3 The CE was created in 2007, and it was very likely that it had its own modus operandi, while hosting some mercenaries from al-Qaeda and possibly receiving some further funding from the organisation.

A review of Dokku Umarov’s speeches posted on websites such as YouTube and field interviews with members of the Chechen community revealed that until 2006 Umarov’s ideas had nothing to do with radical Islam. Salafism likely became an issue because of three factors. First, Umarov respected Abdul Halim Sadulayev and his ability to unite the Chechen insurgency and foreign mercenaries. Sadulayev, who was the fourth president of the Chechen Republic- Ichkeria, a field commander during the wars, and the imam of Argun, managed to bring together foreign and CE fighters, appease Basayev and lay the foundations for a united Caucasus. Therefore, Umarov may have been acknowledging the ideas promoted by Sadulayev.

The second factor that affected Umarov’s decision to create the CE was that his fellow commanders were inclined towards Salafist ideas. Among these commanders were Anzor Astemirov (who is rumoured to have encouraged Umarov to form the CE), Said Buriatsky (who had studied Islam), Shamil Basayev (leader of the radical Chechen wing affiliated with al-Qaeda) and Movladi Udugov (the drafter of the CE declaration); thus, Umarov had no choice but to refocus on Salafism.

However, the most convincing argument in this regard relates to the external context. While one of the most prominent experts in this field, Sergey Markedonov, claimed that the CE was created on the values of radical Islam, the factor of the external support Umarov needed for his survival has to be taken into account. Backed by the Russian Federation, Ramzan Kadyrov, the pro-Russian Chechen president, was able to control the security situation in Chechnya, and Umarov inevitably required external support, which was most probably provided with preconditions – such as strengthening the position of Salafism. Also, Umarov could not completely rely on the local community, which was fragmented as a result of various factors. Thus, Umarov had to adopt Salafism as the driving ideology of the CE for the simple reason that external support made his fight possible. As recent research by Ratelle has demonstrated, support for the global Salafist jihad in North Caucasian society remains partial and eclectic, because radical Islamist views do not directly translate into open support for the CE or international jihad in general.4

Undoubtedly, the factor of Salafism played a role in the CE’s founding. It also curbed Chechen national resistance against Russia. A number of interlocutors in the field (the older generation) claim that the creation of the CE is at least partly a product of the machinations of the Russian secret service. The CE effectively killed Chechen separatism and nationalism, which the Russian secret service was also trying to suppress. Many fighters disagreed with the CE’s Salafism, which replaced the concept of statehood and independence. The current prime minister of the Chechen government in exile, Akhmed Zakayev, added that it was the Russians who discredited the fight of the Chechen people, provoked the international community (as the Congress of the Chechen and Dagestan people did, which resulted in the second Chechen war), and labelled the Chechen’s fight as international terrorism, which has nothing to do with Chechen statehood or Islamic values.

It is pertinent to consider the social-economic context of the imperatives that may have affected the creation of the CE, which may address certain issues surrounding the process. These social-economic imperatives did not have a direct impact on the creation of the CE; however, they helped to mobilise social resistance and strong support for the CE. The local community, together with the insurgency, have been affected by an unstable and fragile social-economic situation, and this should be taken into account. North Caucasus is financed by the Russian Federation, receiving financial injections into its budgets that vary from 55 to 83 per cent of the total. The rate of unemployment is the highest in the Russian Federation. Deeply rooted corruption, nepotism and clan connections have prevailed in the North Caucasus republics and have blocked any foreign investment. Clearly, this contributed to the resistance to the current regime and to some extent opened up opportunities for the creation of the CE in light of social opposition and the struggle for a better life.

It is not possible for this variety of factors to reveal a clear-cut, unequivocal explanation for the founding of the CE. However, it is likely that Umarov was forced to side with the Salafists and plan new projects for the North Caucasian insurgency, which would not have been as successful if it had been based solely on nationalism.

3 The structure of the Caucasus Emirates

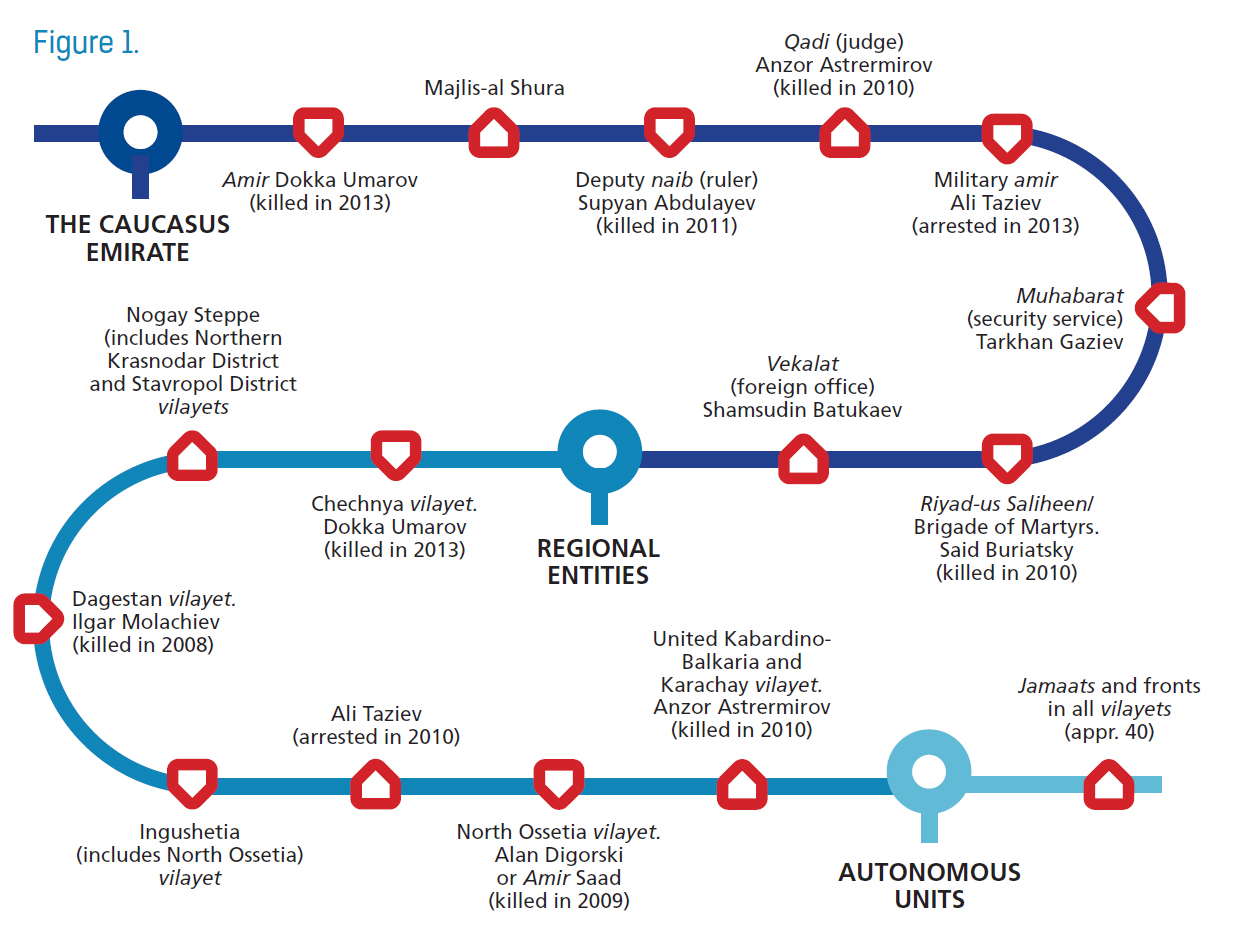

Hahn explains that it would be wrong to see the CE as driven solely by local concerns and lacking central control or a hierarchical structure, because its organisational structure was determined by Umarov by omra (decree) and is a mix of typical network forms.5 Indeed, it seems that the CE operates as a hierarchically structured organisation that includes judicial, political and military branches with a clearly defined top-down decision-making model. The head of the organisation is the amir, who receives the bayat from other amirs. The key roles are taken by the deputy naib (ruler), the military amir and the qadi (judge). The qadi is responsible for the sharia court and all interpretation related to Islam. The sharia courts also resolve disputes between CE members. An example of this is the matter of some Chechen field commanders’ opposition to Dokka Umarov, when commanders Gakayev, Vadalov and Gaziyev accused Umarov in a sharia court of autocratic decision-making and straying from Chechen national ideals. The Majlis-al Shura serves as a consultative body on all CE-related matters and appoints the new amir. There is a further element, the so-called Vekalat (foreign office), which operates abroad and represents the interests of the CE outside the Caucasus. It is also worth mentioning the Riyad-us Saliheen Brigade of Martyrs, which was established under Shamil Basayev, reactivated by Said Buriatsky and incorporated into the structure of the CE. The Muhabarat is responsible for intelligence gathering and security matters.

At a regional level there are five entities or vilayets (administrative divisions) that cover the territory of the North Caucasus. A part of the emirate structure encompasses autonomous combat formations, called jamaats, that operate in well-defined territorial sections of the emirate and beyond. The jamaat leaders are appointed by the amir and approved by the Supreme Council. The emirate’s chain of command is rather unclear, although local amirs must obey the orders of the amir who issues directives. The CE appears to function effectively as an organised bureaucratic machine, with clear lines of authority, terms of reference and laws. For example, in 2015, Dokka Umarov’s brother Akhmed Umarov addressed the issue of a lack of financial accountability in field operations. He presented the issue in writing to the amir, who authorised that it should proceed to the sharia court. Umarov then handed the issue over to the court’s adjudication. This demonstrates that the CE is governed by regulations and laws that members obey. This is slightly more obscure and complicated in the area of military operations because within the framework of the individual vilayets some active and territorially defined jamaats are generally self-sufficient in terms of finances and human resources, and thus enjoy a high degree of autonomy.6 Each jamaat operates autonomously in its territorial area and enjoys almost full freedom of action to decide on its own military activities and operations. Jamaat leaders make decisions to carry out terrorist acts independently and do not consult one another. While the jamaats act on their own, contentious issues can be referred to the amir for final resolution; his decisions would not be ignored. This level of autonomous military action is in response to the offensive operations of Russian troops and Ramzan Kadyrov’s forces, which have been very proactive and efficient in the region. The CE has not been able (or willing) to maintain a typical chain of command, which has been consistently targeted by federal forces and would have ceased to exist if its members had been identified and attacked.

4 Decline of the Caucasus Emirates

The years between 2013 and 2015 constituted a period of crucial changes for the CE for three reasons: changes in leadership (and the subsequent absence of a leader), clashes between IS and CE supporters, and the decreased tempo of military operations.

4.1 Leadership

Inevitably, the CE has undergone many changes in terms of leadership, and this has been the prime factor motivating the changes that the organisation has experienced. Dokka Umarov, the leader and amir of the CE, was targeted by the Russian Federal Security Service and eventually killed in 2013. In March 2014 qadi Ali Abu Mukhammad announced that he would take responsibility for jihad in the Caucasus region and replace Dokka Umarov as the leader of the CE. The appointment of the new amir from Dagestan did not follow the organisation’s procedures, and dramatically changed the internal and external context in which the CE operated. The decision to appoint a non-Chechen leader weakened the links with the Chechen diaspora and undermined support from the Chechen community. Mukhammad’s limited combat experience placed the organisation’s military operations in serious question, although his Islamic education and knowledge of Arabic could have attracted additional support from global jihadist movements. The hub of the insurgency moved to Dagestan and concentrated mainly on the theatre of operations there. In April 2015 Mukhammad was killed in Dagestan and a successor from the Avar people of Dagestan, Magomed Suleymanov, who had had an Islamic education, was chosen to replace him. The decision was taken quickly and there was no information on whether other candidates were considered for the role. His term in office ended after only a few months and he was killed in a security forces anti-terrorist operation in August 2015. No new leader has been chosen since Suleymanov’s death, although some attempts to refer to Akhmed Umarov (brother of Dokka Umarov) as a potential leader were made in September 2015. However, in late October 2015, Akhmed Umarov distanced himself from the fighters who had acknowledged him as their amir. Tarkhan Gaziev, who is a recognised field commander, may be ready to lead the insurgency and has repeatedly promised to return to Chechnya to continue the fight. However, Ekaterina Sokirianskaia explained that the CE could not elect a new leader largely because it is almost impossible to follow the procedure for electing a new amir and there is clearly a shortage of leaders who possess both the necessary knowledge of Islam and relevant battle experience.

4.2 Clashes with IS

IS’s penetration of the area and the resultant clashes within the CE have adversely affected the latter organisation. Mukhammad had to deal with the schism in the emirate’s ranks and the trend of young insurgents travelling en masse to fight in Syria and Iraq. On 21 November 2014, Suleiman Zailanabidov, from the commander of the insurgency in Khasaviurt, pledged his bayat to IS, thereby publicly confirming the schism in the CE. He was followed in December 2015 by the amir of Dagestan, Abu Muhammed Kadarsky, and the field commander who led the insurgency in Shamilkalinski district, Abu Muhhamed Agachaulski. Suleymanov inherited the contentious issue of the schism, which reached a peak in June 2015, when Aslan Byutukaev, the commander of the Riyad-us Saliheen Brigade of Martyrs, pledged the bayat to IS. This was followed by a joint message posted on YouTube on 21 June 2015 in which all the CE field commanders pledged the bayat to IS, which reacted positively and quickly and appointed Abu Muhammed Kadarsky as chief of the newly established IS Caucasus vilayet. Suleymanov, the last CE amir, was killed in action in August 2015, and the CE as such should have ceased to exist. It is possible that there are small groups operating in various geographical areas that have not pledged the bayat to IS. For example, the CE vilayet of Nogai Steppe has not announced its decision with respect to IS, while former followers of Magomed Suleymanov may well be operating independently under the CE banner. The amir of the United Kabardino- Balkaria and Karachay vilayet, Salim, made a statement in December 2015 addressing the schism in the vilayet and urged fighters to return to the Caucasus. Nevertheless, the Kabardino- Balkaria and Karachay vilayet has been gradually decimated since its amir, Anzor Astemirov, who was also the CE’s qadi, was killed in March 2010. The Dagestanis are possibly the only force that could significantly revive the CE to something approaching its previous strength, but in Gordon Hahn’s opinion this is unlikely, since their religiosity and Islamism draw them to IS’s brand of jihadism.7

4.3 Operations

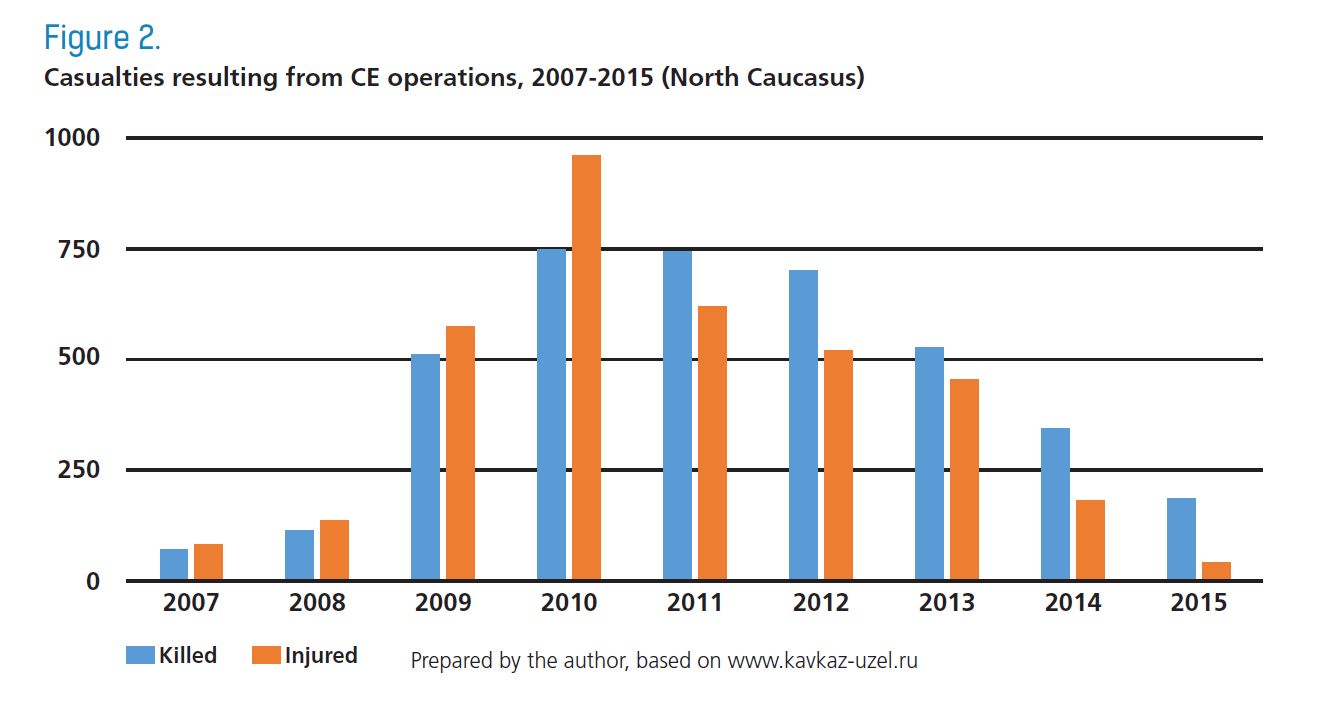

The internal schism has had a negative impact on the tempo of CE operations. Figure 2 clearly demonstrates a steady decrease in CE casualties/ casualties resulting from CE operations, from 749 killed in 2010 to 188 killed in 2015. No major terrorist acts took place in 2015. In 2013, Dokka Umarov threatened to start a fire at the Sochi Olympics. This received significant attention from the international community; however, nothing actually transpired. Since then there was one noteworthy attack in which a CE group ambushed a police checkpoint in Grozny on 4 December 2014, killing three officers. This resulted in a massive counterattack from Chechen security forces that left 25 killed and 36 wounded. This kind of response from the security forces prevents the CE from generating resources and substantial support for field operations; such operations will therefore decrease.

Finally, the fact that not all CE leaders have pledged the bayat to IS and the strong impact of CE opposition to foreign representations indicate that a few scattered units will continue to operate under the CE banner, albeit with a severely limited military chain of command, poorly functioning communication channels and scarce resources, resulting in fewer operations.

Notes

1 See D. Rhodes, “Salafist-Takfiri Jihadism: The Ideology of the Caucasus Emirate”, Working Paper No. 27, Herzliya, International Institute for Counter-Terrorism.

2 G. M. Hahn, Getting the Caucasus Emirate Right, Washington, DC, Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 2011.

3 M.-M. O. Mohamedou, Understanding Al Qaeda: Changing War and Global Politics, London, Pluto Press, 2011, pp.85-87.

4 J.-F. Ratelle, “A Comparative Analysis of the Caucasus Emirate Islamic Ideology within the Global-Salafi Jihad”, CERIA Brief No. 5, January 2015.

5 G. M. Hahn, Getting the Caucasus Emirate Right, Washington, DC, Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 2011.

6 E. Souleimanov, “The Caucasus Emirate: Genealogy of an Islamist Insurgency”, Middle East Policy, Vol.17(4), 2011, pp.155-168.

7 G. M. Hahn, Getting the Caucasus Emirate Right, Washington, DC, Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 2011.

About the author

Grazvydas Jasutis is a research fellow at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, and teaches post-Soviet security courses at the General Jonas Zemaitis Military Academy and at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science at Vilnius University. He has held various positions in EU missions in Georgia, Burkina Faso, and Indonesia, as well as the OSCE missions in Kosovo and FYROM.