Cross-examining the Criminal Court

23 Jul 2018

By Céline Barmet for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The this article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) as part of the CSS Analyses in Security Policy series in October 2017.

Fifteen years ago, the first permanent International Criminal Court took up its work. The establishment of this tribunal was a success that sent a strong signal against impunity for human rights violations. Today, however, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is struggling against stiff resistance from various quarters. In the interests of efficient prosecution of crimes, the court’s mandate must be supported more forcefully.

The adoption of the Rome Statute in 1998 and its entry into force on 1 July 2002 were milestones in the development of international criminal law. For the first time, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has made it possible for a permanent international body to prosecute the perpetrators of the most atrocious crimes. It supports the rule of law and fosters the systematic implementation of international humanitarian law. In doing so, the ICC has institutionalized the maxim that certain crimes are banned under all circumstances and that the victims of the most serious violations of human rights have a right to justice and reparations. By sentencing individuals for crimes of sexual violence, recruitment of child soldiers, and the destruction of cultural heritage, the court has furthermore succeeded in creating important precedent and giving a strong signal.

Nevertheless, the ICC finds itself confronted with diverse challenges due to ongoing global tensions. Authoritarian regimes are blocking the implementation of universal human rights, while only a fraction of all violations of international law is sanctioned. Moreover, political circumstances frequently obstruct the work of the ICC. For instance, the court cannot initiate an investigation in Syria until the UN Security Council (UNSC) refers the situation to the court’s jurisdiction – a move that veto powers Russia and China have so far prevented. At the same time, neither Russia, China, nor the US have ratified the Rome Statute, and Russia actually withdrew its signature in November 2016. This means that the ICC is missing important member states. On the other hand, certain African states feel unfairly treated by the court, and have threatened to withdraw. The withdrawal of Burundi will take effect on 27 October 2017. Effective cooperation between some African governments and the court is hampered by divergent priorities and differing legal opinions, for instance, concerning the execution of arrest warrants and the transfer of evidence.

Ultimately, the ICC can only function within an international framework that shares its value system and supports the court’s mandate. If justice is to be served against the most dangerous criminals – as stipulated by the Rome Statute – in the interests of deterrence and the prevention of atrocities, support for the ICC at the multilateral level is not sufficient. The moral authority of the ICC should also provide motivation to strengthen regional and national judicial systems in accordance with international law. Switzerland, which feels particularly obligated to the ICC due to its humanitarian tradition and its appreciation of international (humanitarian) law, actively supports this cause.

How the ICC Operates

The first calls for the establishment of an international criminal court were voiced as early as the 1870s, although international criminal law only came into being after the Second World War and the subsequent war crimes trials in Nuremberg and Tokyo. After 60 states had ratified the Rome Statute of 1998, the ICC was finally established on 1 July 2002, with its seat in The Hague. As of October 2017, it will have 123 member states. The Rome Statute consists of three main parts: the Court; the Assembly of States Parties as the reviewing and legislative body; and the Trust Fund for Victims, which finances reparations. The operating budget for 2017 is €141.6 million, funded by the member states. In addition to its headquarters, the ICC maintains a liaison office in New York and six field missions on the African continent. In total, the court has about 800 staff members from approximately 100 countries. Unlike the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR) and the special tribunals for Sierra Leone, Cambodia, or Lebanon, the ICC derives its authority not from a treaty between the respective state and the UN or even from a UNSC resolution but from an independent multilateral agreement.

The ICC’s mission is to hold accountable individuals – not states, which come under the purview of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) – for four fundamental violations of international criminal law: 1) genocide; 2) crimes against humanity; 3) war crimes; and 4) the crime of aggression. The jurisdiction of the last one of these crimes was only defined in an additional protocol in 2010 and cannot be prosecuted before the end of 2017. Essentially, the court’s purpose is to focus on bringing to justice the main perpetrators responsible for such grave crimes. By acting against impunity, the ICC also aims to contribute to the prevention of such crimes. At the same time, it is important to ensure that any investigation is in the best interest of justice and of the victims. Injured parties not only have a right to reparations but may also give testimony as witnesses at all stages of the court proceedings.

The ICC operates on the principle of complementarity, which means that the main responsibility for prosecuting the four defined crimes lies primarily with the states themselves. The ICC was established to play a complementary role (“court of last resort”) and only deals with cases that national courts do not prosecute under the standards of international criminal law due to lack of interest, lack of resources, or lack of capacity.

Moreover, the ICC can only prosecute crimes carried out in one of the ICC member states or by an adult citizen of an ICC member state. This authority may expand to non-member states if the UNSC refers a matter to the ICC or if the state in question agrees to accept the court’s jurisdiction temporarily. It may only deal with crimes committed after the entry into force of the Rome Statute, or after the date of ratification for those countries that had not yet joined as of 1 July 2002. Assuming that these criteria are met, cases may be referred to the ICC chief prosecutor by authority of a member state, the UNSC, or the chief prosecutor’s office itself (proprio motu). In order to initiate proceedings through this last instance, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) requires the court’s consent. Before an investigation can be initiated, the OTP must verify in preliminary examinations whether the abovementioned criteria are met and whether the situation falls within the scope of the ICC’s jurisdiction.

Membership

With 123 members (as of October 2017), the ICC is one of the biggest international organizations. Many states from Western and Eastern Europe, Africa, and South America have joined it, while only a few Asian countries have ratified the Rome Statute. Global heavyweights like the US, Russia, and China do not intend to join the ICC. As permanent UNSC members, they can refer situations to the ICC but avoid prosecution for their own citizens. Thus, the ICC’s ability to act against impunity for the most serious crimes is restricted to a certain geographic area. The UNSC could adjust the balance somewhat by referring situations in non-member states, but it does so in all too few cases. The result is an inequitable situation that damages the effectiveness and independence of the ICC.

The ICC’s Africa Complex

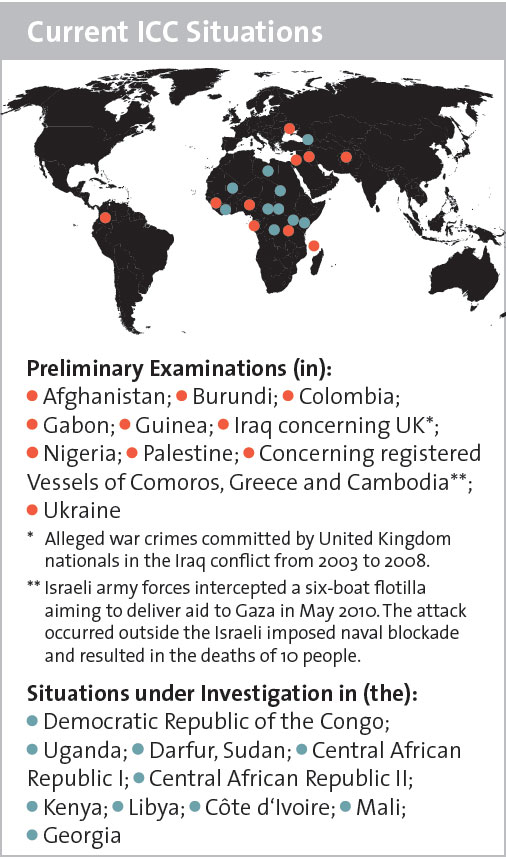

A frequently voiced criticism that closely relates to the question of universality is the charge of selective justice to the disadvantage of African states. While the ICC currently engage in preliminary investigations in a number of states outside of Africa (see chart), nine out of ten situations that actually end up being dealt with in court relate to African states. Many of these rank high in the Fragile States Index and have little capacity to investigate serious crimes themselves. Therefore, African states have referred situations to the ICC on their own authority in five cases. The investigations of the situations in Kenya, Libya, Côte d’Ivoire, Georgia, and Darfur were, however, initiated with external assistance, i.e. by the UNSC or the ICC chief prosecutor. Among these were also the indictments of former Sudanese president Omar Al Bashir and Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta.

The African Union (AU) argued that the arrest warrants for these two individuals violated the immunity of high-ranking AU state officials, and called on its members not to cooperate with the ICC in either of these cases. Furthermore, the AU accused the ICC of trying to influence political power structures in Africa in a neo-colonial manner and of jeopardizing the Sudan peace process with the arrest of Al Bashir. Mainly Kenya instigated this aggressive rhetoric on the part of the AU, and the implied attempt to discredit the ICC, with other governments joining in for fear of possible ICC prosecution. This was likely also the key reason for Burundi’s decision to withdraw from the ICC, effective on 27 October 2017. In response to the violence in Burundi following President Pierre Nkurunziza’s bid for re-election to an (unconstitutional) third term in office, the ICC chief prosecutor initiated preliminary investigations in April 2016. Subsequently, the East African state announced its withdrawal in autumn of that year, and will be the first state to leave the ICC after 13 years of membership. Meanwhile, the withdrawals of South Africa and the Gambia, which they announced in autumn 2016, have been cancelled.

Other critics argue that while the Rome Statute provides for the prosecution of the most serious crimes, it ignores other offences that are of importance to the African continent (piracy, corruption, human trafficking, or illegal exploitation of resources). The call for “African solutions for African problems” has spurred the AU’s efforts since 2014 to give the yet to be established African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR) the authority to prosecute international crimes. If this additional protocol were actually to be ratified, the ACJHR would have jurisdiction over the same crimes as the ICC. Though regional efforts to combat impunity are to be welcomed in principle, especially with a view to the principle of complementarity, cooperation with the ICC should be adopted as part of the regional framework as a matter of urgency. It is important to note that the original motivation for these efforts to expand the ACJHR’s jurisdiction lies in disputes with the ICC, and that the ACJHR wants to guarantee acting heads of state and high-ranking officials immunity ex officio; this makes it all the more crucial to ensure that efforts at the global level are not undermined.

Prosecutions and Convictions (as of 15 August 2017)

To date, the ICC has prosecuted 25 different cases and put 42 defendants in the dock (41 of them citizens of African states). It issued 31 arrest warrants and 9 summonses. 15 wanted individuals are currently still at large, while 6 people are imprisoned in the ICC detention center. In total, the court has so far sentenced 8 individuals in 5 different cases and 3 situations (Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Central African Republic I (CAR I), and Mali) for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and offences against the administration of justice. One person was acquitted in another case. It handed down the first sentence in spring of 2012 in the case of former Congolese militia leader Thomas Lubanga (DRC situation). He was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment for war crimes due to his recruitment of child soldiers during the 2002 – 3 civil war. In another case, the former militia commander-in-chief and vice president of the DRC, Jean-Pierre Bemba (situation CAR I) was sentenced – for rape inter alia – to 18 years of prison. In the Bemba case, the court categorized the crime of rape as a war crime and a crime against humanity which thus marks an important precedent concerning crimes of sexual violence. Another key judgment was handed down in September 2016 against Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi (Mali), who was sentenced to nine years in prison for the intentional destruction of historic and religious monuments. This was the first trial to deal exclusively with the destruction of cultural heritage as a war crime. It also marked the first prosecution of an Islamist militant in the ICC.

Incumbent high-ranking state officials, some of whom are also alleged dangerous felons, often enjoy immunity in their own countries, and can wield their authority to compromise the independence of the national judiciary. That is why the existence of the ICC and its action against impunity is of great significance. However, crimes can be prosecuted to the ICC’s standards in Africa too, as evidenced by the trial of former Chadian president Hissène Habré. A special tribunal established by the AU and Senegal sentenced him to life in prison for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and other violations of international humanitarian law.

The Crime of Aggression

The crime of aggression, as described in the Rome Statute, refers to a state’s use of armed force against the sovereignty of another state in a manner incompatible with the UN Charter. Due to the difficult nature of negotiations, the crime was given its legal definition not in Rome, but in Kampala, 12 years later. The requirement for its activation was that at least 30 states had to ratify the status change, which the assembly of states parties (ASP) then had to confirm one year later. Since 34 states have ratified it to date, the ASP is theoretically required to finalize the process in December 2017. However, the member states remain in disagreement over the legal interpretation of the article – despite a compromise found at Kampala with the so-called “opt-out option”, which gives member states the option of revoking the court’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression through a simple declaration. However, France, the UK, Japan, Norway, Canada, and Colombia argue that the Kampala agreement is ambiguous on the question of jurisdiction. They have thus cast doubt on the viability of this compromise, fearing a residual risk for their own citizens.

Lack of Cooperation

ICC member states are obliged to cooperate with the court. In case of referrals by the UNSC, this obligation also extends to non-member states. For the ICC, which has no police force of its own, such cooperation is indispensable to fulfill its mandate. Only the states can arrest individuals wanted by the ICC, render them to The Hague, freeze assets, enforce sentences, or hand over incriminating evidence to the ICC. In this respect, the prosecutions of former Sudanese president Al Bashir and Kenyan President Kenyatta were handled in a particularly unfortunate manner. Al Bashir has traveled unhindered through several African ICC member states without being served the arrest warrant that has been outstanding since 2009. At the AU summit in Johannesburg, too, the South African government refused to execute the warrant against Al Bashir, arguing that he enjoyed immunity, which caused great outrage internationally. In July 2017, the ICC confirmed that South Africa’s actions in this case violated its duties of cooperation under the Rome Statute, since diplomatic immunity prevents the court under no circumstances – even in the case of incumbent heads of state – from exercising its jurisdiction. Nevertheless, Al Bashir remains at large.

The fact that the proceedings against Kenyatta and his Deputy President William Ruto had to be closed due to lack of evidence is also illustrative of the court’s impotence in the face of individual states’ political intransigence. Fortunately for Kenyatta, Kenya refused to release potential evidence to the ICC. According to the current chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, the Kenyan government is also responsible for the intimidation of potential witnesses. Both Kenyatta and Ruto remain in office in Kenya to this day.

Switzerland and the ICC

Due to its advocacy against impunity, for the implementation of human rights, and in favor of strengthening the international criminal jurisdiction, Switzerland actively supports the cause of the ICC. Accordingly, Switzerland took part in the formation of the ICC and ratified the Rome Statute on 12 October 2001. Further, Switzerland was significantly involved in the negotiations on the definition of the crime of aggression in Kampala in 2010. As the depositary for the Geneva Convention, Switzerland is engaged in various bodies in upholding international humanitarian law, especially with a view to the UN Charter’s ban on the use of force. For instance, in January 2013, it called upon the UNSC to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC. However, although 56 other states supported the proposal, it was ultimately unsuccessful. Increasing the efficiency of ICC trials is another major concern of Switzerland. To this end, the Swiss government organized two retreats in Glion, Canton Vaud (Glion I and II) in September 2014 and April 2016, with invitees including high-ranking representatives of the ICC, member states, and civil society. Glion I was based on an independent expert report a Swiss coordinated, and laid out how ICC trials could be more efficient and more accelerated in practice. The court later took up some of the points under discussion, and the ICC’s efficiency has been one of the main priorities of the current president, Silvia Fernández de Gurmendi (2015 – 18). Glion II developed and substantiated performance indicators that can help member states better assess the court’s efficiency. Moreover, Switzerland supports the functional capabilities of national legal systems. In May 2017, it funded a conference for African ICC member states in Dakar. Topics on the agenda included the implementation of the principle of complementarity and cooperation between the African judicial systems and the ICC.

The UNSC’s support for the ICC is also politically motivated and occasionally poor. Although the UNSC has referred situations to the ICC, it did not take any meaningful follow-up measures to implement those referrals thoroughly and comprehensively. Moreover, despite the efforts of many states, the UNSC has still not referred the Syria situation to the ICC. At least the UN General Assembly in December 2016 managed to create a mechanism to support investigations and evidence gathering related to serious international crimes committed in Syria since 2011 and is preparing prosecutions in national, regional, and international courts. The ICC is also currently considering whether it can charge adherents of Islamic State (IS) militias who are citizens of ICC member states.

The international community must do more to prove that it is serious about supporting the criminal prosecution of severe violations of international law and preventing such crimes. All too often, the ICC remains dependent on the political balance of power and is forced to postpone certain investigations, or not even to initiate them. This continues to deny justice to innumerable victims of atrocities, and the court is in danger of losing credibility and relevance. This would be disastrous, since the number of cases before the ICC is likely to multiply given the global potential for conflict, which will be compounded in the future by population growth, resource scarcity, climate change, and migration movements. This will also increase the pressure on the ICC’s limited capabilities. On the other hand, the ICC must convince regional and national partners in the areas of peace support, conflict prevention, and human rights as well as the civilian population to extend complete support to its mission. To this end, relations must be strengthened and dialogue must be fostered. Member states are also required to strengthen their engagements, since the increasing number of ICC prosecutions outside of Africa will accordingly also require increased funding.

About the Author

Céline Barmet is a research assistant at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. She has previously worked at the Swiss embassy in The Hague and served as a delegate for the ICC.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.