Lost in Regulation: The EU and Nord Stream 2

13 Nov 2017

By Severin Fischer for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) as part of the CSS Policy Perspectives series in November 2017.

The pipeline project Nord Stream 2 truly is a dividing issue. In 2015, Gazprom and five partner companies from EU member states announced that they would build a second 9.5 billion Euro twin set of gas pipelines for delivering an additional 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia to Germany on the Baltic seabed. Since then, a broad debate on implications for foreign, security and climate policies has emerged. While for two years, heads of states and governments from Central-Eastern Europe and Baltic Sea neighbors have heavily criticized the project in the European Council, and letters from national capitals and the European Parliament have been sent to the European Commission objecting to the project, adequate legal measures to prevent the construction process have remained unclear. The main reason for this is that Nord Stream 2 neither relies on public financing from the EU or member state budgets, nor on a multilateral agreement between governments. As a commercial investment largely outside of EU member states’ territorial jurisdiction, it is thus not easy to stop.

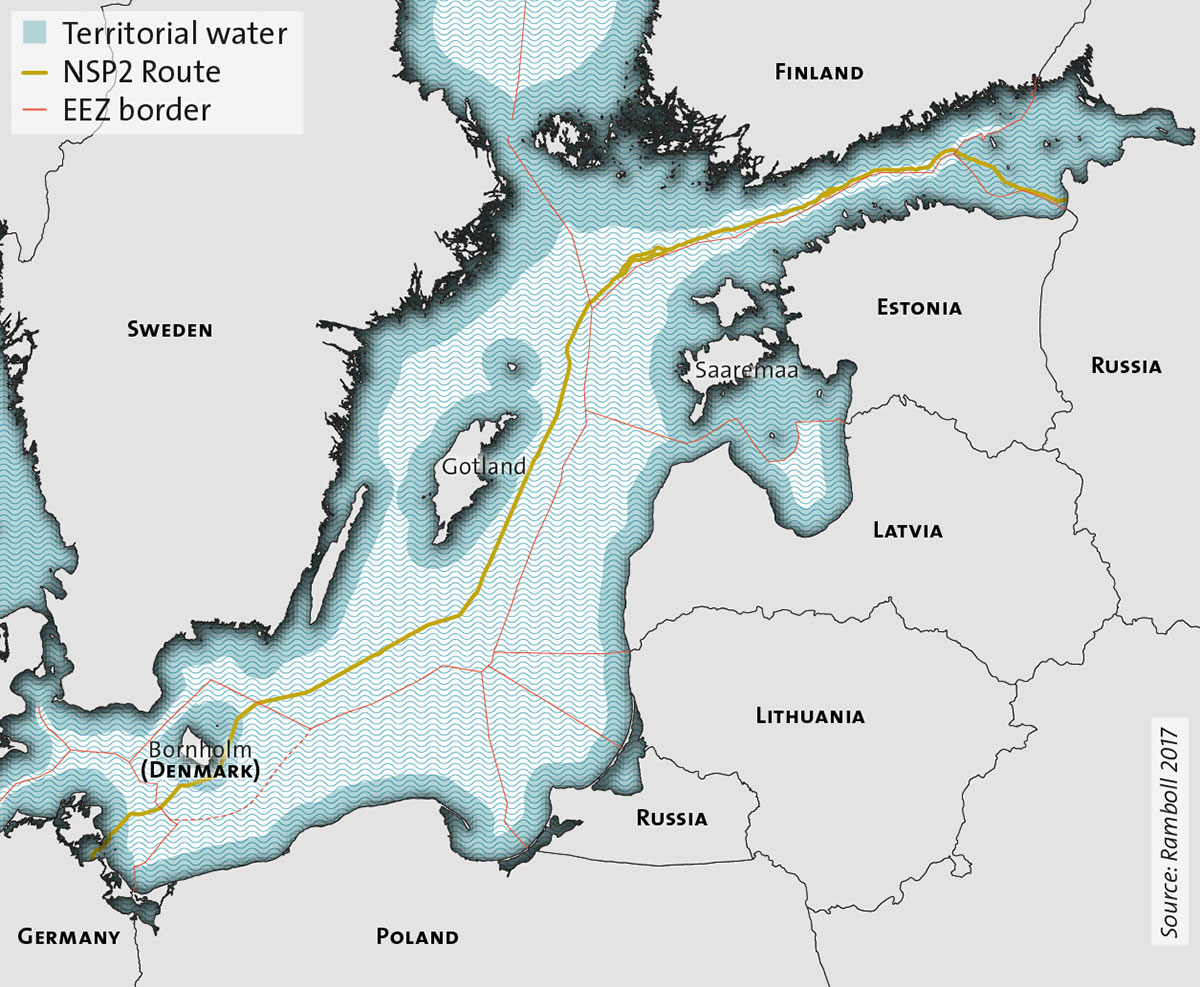

This does not mean, however, that there is a lack of legal frameworks. Like other infrastructure projects, the Nord Stream 2 developers have to fulfill the permitting criteria described in national laws of Baltic Sea littoral states, in EU law and in international law under the “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (UNCLOS) and the Espoo Convention on environmental aspects. Only Denmark’s coalition government is trying to prevent granting a permission by a new law, allowing the foreign minister to stop infrastructure projects in territorial waters on the basis of security concerns. Depending on the development of this domestic law-making procedure, the Nord Stream 2 developers could be forced to avoid Danish territorial waters and change the anticipated route. This would result in a delay of pipe laying, but most likely not stop the project. Contrary to cases of publicly funded infrastructure, the realization of the Nord Stream 2 project is not subject to the agreements reached in political negotiation processes between states. Thus, unless the project developers act against existing laws, direct political influence on the pipeline construction remains limited.

Key Points

- The heated debate about Nord Stream 2 has shifted from a geopolitical

focus towards a question of the applicable regulatory framework - In the EU’s political processes, the question is no longer whether the

building of the pipeline should be stopped, but how it will be

operated after construction - In its search for a new specific regulatory framework to cover the

pipeline, the Commission has got lost in legal inconsistencies - A new German government might change the country’s position

towards Nord Stream 2, but will need to thoroughly assess its

political options

The Commission and Nord Stream 2

While Commission representatives have for the last two years repeatedly claimed, that they do not “like” the Nord Stream 2 project “politically”, it remained unclear, what this would imply in legal terms. In a first step, initiated already in 2016, the Commission asked its legal service to clarify the applicability of its regulatory framework for the natural gas market – the Third Internal Market package from 2009 – on the planned pipeline. In an internal document, the Commission’s legal service denied the applicability, since the EU’s regulatory framework would not cover offshore pipelines from third countries up to the entry point in the EU system some kilometers inland, where natural gas is distributed by connecting pipelines further into the internal market. In a second step, in February 2017, the Commission’s Energy Directorate, contrary to its internal legal advice, asked the German regulatory authority, the “Bundesnetzagentur”, to apply the 2009 rules on the project. The German regulator declined to do so, referring to its own reading of EU law and to other cases of import pipelines, in which EU rules were explicitly not applied, also hinting at the assessment of the Commission’s internal legal service.

While the Commission felt that political pressure to take measures against the project was growing, it found itself locked in a difficult situation: Either it could disregard the assessments of its internal legal advisors and the regulator that would have to implement its policy; or it could upset those actors in the EU context, who had trusted the Commission to use every possible instrument against the project. In this situation of difficult political expectation management, the Commission chose a third way: shifting responsibility to another institution and putting the ball in the field of member state governments in the Council.

The IGA Mandate

The Commission’s approach to externalize the problem of dealing with Nord Stream 2 involved two aspects. First, it moved to a different arena. While the EU’s internal energy market is a domain of the Commission, in the field of international energy governance, member states have an institutional prerogative. Second, the Commission had to find a reason for this move to the international arena. In order to do so, it constructed the problem of a “legal void”, claiming that a conflict of laws on energy regulation was apparent in the Baltic Sea, knowing full well that EU energy market regulation has never been used for comparable import pipelines before, not to mention an application in the EEZ. To solve this artificially constructed problem, the Commission asked the Council for a mandate to start negotiations on an Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) with Russia. This IGA should include all important elements of the EU’s domestic approach: A third party access to the pipeline, unbundling of ownership and operation of the pipeline, tariff regulation and transparency.

This Commission approach was either doomed to fail, or intended to. First, it was unlikely to collect the legally required majority of governments to agree on providing the Commission with such a mandate. This difficulty stemmed from two sources: on the one hand, member state governments feared a precedent for an institutional transfer of power to the Commission; on the other hand, and even more importantly, the reasoning for the exercise (the claim about a “legal void”) was already questioned by many governments and later wiped off the table by the Legal Service of the Council. But even if member state governments would have been convinced and legal questions were put aside, it seems unclear, why the Russian government would have entered negotiations about an IGA, voluntarily introducing EU energy market rules in the EEZ and in Russian territorial waters, having in mind, that this was explicitly not a precondition for the construction process.

For the Commission, the purpose of proposing the IGA procedure was meant to satisfy the demands of Denmark, Sweden and Central-Eastern European states to act, while at the same time, claiming that reasons for failure of this attempt lay with member state governments in the Council. However, no measure comes without costs: First, the debate about an IGA incrementally shifted the political controversy about Nord Stream 2 from stopping the construction of the pipeline towards the issue of how to operate an already built pipeline. Second, it raised the question as to why the Commission refrained from applying EU energy market regulation in the territorial waters of its member states in the first place, while at the same time claiming a conflict of legal systems between Russia and the EU in the Baltic Sea. Since this second question received growing attention and political pressure was built up, the Commission was forced to act again.

Changing the Gas Market Directive

Many observers of the debate were surprised when the Commission announced during a parliamentary hearing in October 2017 that it was planning to modify the Gas Market Directive, the cornerstone of EU energy market regulation in the area of natural gas. The proposed amendment includes the regulation of offshore pipelines in the EU’s territorial waters. So far, the Gas Directive does not explicitly cover the regulation of offshore pipelines from third countries arriving on EU territory. The text of the Directive rather defines an “interconnector” as a pipeline between two EU member states and therefore does not refer to import pipelines. This non-applicability was also stated by the Legal Services of the Commission and the Council and by the German regulator. Recognizing the complexity of this situation, the Commission has now proposed to change the law in order to include import pipelines from third countries in the EU’s energy acquis. At this moment, it would be appropriate to highlight three points.

First, the Commission has created a fundamental friction in its own argumentation. If Brussels sees the need to change the directive to apply EU energy market regulation to the parts of the pipeline that run in territorial waters, the claim about a “legal void” is obviously unjustified. There cannot be a conflict of law systems, if a change to the law is required in order to make the EU law applicable in the first place. This inconsistency in argumentation leads to a conclusion that the IGA mandate procedure is based on an assumption which the Commission has already declared non-existent with its proposal.

Second, only the amendments to the directive would create a conflict between legal systems, stretching beyond the Nord Stream 2 issue. A “legal void” would be created not only between Russia and the EU, but rather between the EU and all other natural gas suppliers using offshore pipelines. Since EU law cannot be applied selectively, the territorial water parts of pipelines in the Mediterranean Sea and Nord Stream 1 would also need to be covered. An exemption clause for these pipelines can hardly be justified, since this would be a discriminatory measure. If also applied, it would change the business case for pipeline operators and create legal disputes with Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia as well, not to mention any future projects.

Third, although the Commission has, in agreement with European Parliament representatives, proposed a fast-track procedure for the amendment to the Gas Market Directive, the necessary majority in the Council is far from certain. Besides Germany, also Italy and Spain would be affected. The risk of relying on exemptions scrutinized by the Commission on unspecified political grounds, could hardly be accepted. Additionally, several member states with potential future offshore gas production could be skeptical as well.

Despite questions around the political process of introducing EU energy market regulation on the territorial parts of import pipelines, the Commission’s proposal raises additional concerns about equal treatment. So far, natural gas arriving via pipeline at the entry point of the EU’s gas market rightly falls under the EU’s provisions from that point onwards. The same applies to competing Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) after it has left the regasification terminal in the EU, but not from the point onwards, where the LNG cargo arrives in the EU’s territorial waters. Comparing these cases, the added value of an application of EU energy market regulation on the very last section of an import pipeline remains – from a regulatory point of view – questionable.

Further Reading

The Council Legal Service’s assessment of the European Commission’s negotiating mandate and what it means for Nord Stream 2 Katja Yafimava (Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Energy Insight: 19, 2017)

The author describes the IGA mandate case and offers three possible scenarios for the political process.

Risks of Expanding the Geographical Scope of EU Energy Law

Kim Talus, Moritz Wüstenberg (European Energy and Environmental Law Review, October 2017)

A good assessment of the legal context and the risks included widening the scope of EU energy market regulation.

Nord Stream 2 – A Political and Economic Contextualization

Kai-Olaf Land, Kirsten Westphal (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP Research Paper 3, 2017)

The authors offer a broader political and economic perspective on the debate around the Nord Stream 2 project.

The way forward with a new German government

Germany’s approach towards Nord Stream 2 is crucial not only for geographical reasons, but also due to its political weight in the Council. Since the beginning of the controversy, Chancellor Angela Merkel has referred to the project as a commercial activity that has to be treated in the same way as comparable projects under EU rules. This position has included resisting Commission attempts to overstretch competences or arbitrarily changing the legal environment for the project.

After the federal elections of September 2017, a new government consisting of the conservative CDU/CSU together with the liberal FDP and the Greens is likely to be formed. Depending on the outcome of the negotiations on a coalition agreement, a more critical stance is possible, since the Greens and parts of CDU/CSU and FDP also oppose the pipeline. If the new coalition government states its opposition towards Nord Stream 2, it will certainly earn some credit points from actors in the fields of foreign and environmental policies. At the same time, the new government will have to explain what this change in perspective implies in reality.

Since the permitting procedure in Germany is already well under way, political interference in order to stop the construction permit process is legally problematic and politically unlikely, unless a new set of sanctions against Russia is agreed on EU level. One way to buy time would be to support the Danish government in finalizing its national law and politically pressuring Denmark’s foreign minister to deny the construction permission. However, this would rather have the effect of delaying the building process, until a re-routing has happened, and not stop the project altogether.

Looking at developments at EU level, a new German government could support the Commission’s approach for a mandate to negotiate an IGA with Russia and a change to the Gas Market Directive in the Council. This, however, would also not stop the building process, but create legal difficulties in the operation of the pipeline in the country after it has been built. For the coalition partners, it might create at least two structural problems: First, besides the specific Nord Stream 2 case, is a transfer of power from the member state level to the Commission in the sphere of negotiating an IGA, a precedent for energy projects in the future? And, second, should the new government allow to politicize energy market regulation arbitrarily for foreign policy purposes, with implications for the economic and political environment of gas trade by offshore pipeline EU-wide? After considering these broader political implications, it seems more than likely, that a new government will focus on a connected topic instead: If serious claims about energy security risks or market foreclosure in the EU’s gas market are raised by EU partners, Germany will have to give guarantees for seamless market functioning in the future and consider energy security concerns from neighboring states more thoroughly.

About the Author

Dr Severin Fischer is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich.

Thumbnail iexternal pagemagecall_made courtesy of beeveephoto/Flickr. (CC BY-SA 2.0).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.