Migrants in the Mediterranean: Easy and difficult solutions

1 Nov 2017

By Mikkel Barslund and Lars Ludolph for Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS)

This article was external pagepublishedcall_made by external pageCentre for European Policy Studiescall_made on 12 October 2017.

On the issue of migration, all eyes are now focused on the so-called central Mediterranean route, which runs primarily from Libya to Italy. Until July of this year, irregular crossings from Libya to Italy were on course to reach a record high for 2017 of more than 200,000 arrivals. Given its reputation as the world’s deadliest migration route, this would have meant a record number of drownings as well.

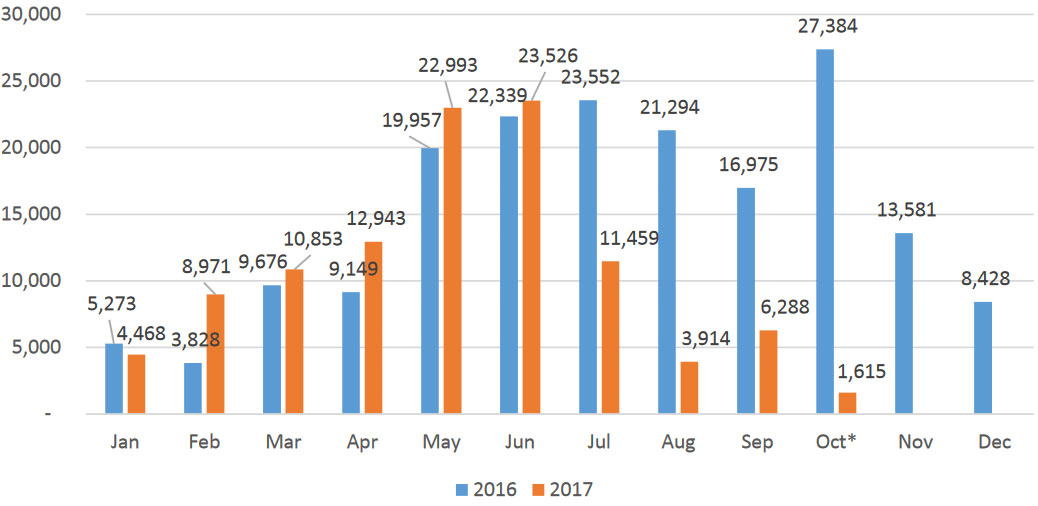

In August and September, the number of arrivals in Italy suddenly dropped to between a quarter and a third of comparable numbers before the summer (Figure 1).1 The reasons for this development are not readily apparent. The number of people coming into Libya along migration routes from neighbouring countries has decreased in the last year, according to the International Office of Migration (IOM), which has also beefed up its much-needed assistance programme of voluntary return of migrants trapped in Libya. There is also some evidence that migrants are re-routing their itineraries towards the Western part of the Mediterranean. But none of these factors can explain more than a fraction of the dramatic drop in the number of arrivals. The fragile and heavily contested Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that Italy signed with the UN-backed Libyan government in February of this year is likely to have played a more important role.2 The MoU talks about resuming past cooperation between Italy and Libya on irregular migration and security issues, with Italy providing technical assistance to border and coast guard operations and financing for development initiatives in Libya.

Figure 1. Arrivals in Italy via the central Mediterranean route, 2016-17

Tracking exactly where and to whom the money from Italy, supported by the Commission’s July Action Plan,3 is ultimately flowing is not an easy task. International media reports on the situation in Libya rarely make for happy reading, nor are the rumours of smugglers turned into coast guard officers overnight. And human rights violations hover over the area as a constant threat.

These are the disquieting realities that prompt many to insist that “EU member states cannot work with Libya”. Given the political salience and importance of migration, however, this attitude has always been naïve. The simple truth of the matter is that working with Libya and a few other countries along established migration routes has always been a potentially easy solution to a complex problem, and it was thus only a matter of time before policymakers would succumb to it. With more than half of the Italian population supporting cooperation with Libya to curb irregular migration, this point has long since been reached.4

Undeniably, Libya does not make for an ideal partner. But, it is an easy partner whose motivations are clear: money and equipment are always welcome. And even though Italy and, by implication, the EU, are now highly vulnerable to mood and power swings within Libya’s militias (with the fighting in Sabratha a case in point), it is likely that additional money can resolve future differences. Furthermore, Italian cooperation with – albeit more stable – Libyan partners is well-tested territory that has been shown to work in the past.

The difficult way forward

There is an alternative to the current state of affairs, which does not involve going back to the unsustainable situation pre-summer 2017. But it does involve more actors and is much harder to implement. It also tackles the root cause of the problem with the Central Mediterranean route: the vast majority of arrivals to Italy are not eligible for protection and as such should be returned to their countries of origin. At present, however, return rates from EU member states are low, making landing on EU soil a de facto ticket to stay and causing public sentiment to turn more and more hostile towards irregular migrants in EU member states.

As a first step, African countries, the main countries of origin, must be persuaded to take their own citizens back. They are often reluctant to do so. One reason is that the diaspora is an important source of remittances and facilitates trade opportunities. Returning people is also unpopular with destination country governments and their voters. Therefore, as suggested by the European Stability Initiative,5 effective agreements on returning migrants should focus on future migrants, not the current stock of rejected asylum seekers. The expectation of being immediately repatriated will – over time – decrease the number of crossings by those migrating primarily for economic reasons. But this approach is only sustainable if asylum procedures, accompanied by all the necessary conditions to safeguard human rights, are conducted relatively swiftly. Implementation of this plan would remain foremost with the EU member states. Italy in particular must do the heavy lifting, and, potentially supported by the European Commission, must aim to reduce the length of its asylum procedures.

The second step involves offering a pool of work permits in European labour markets to African countries that cooperate on returns. Not only will this make effective return agreements more likely to happen in the first place, it will also provide a needed helping hand in achieving long-term development in many countries. Work permits can be combined with investment in on-site training facilities, which would facilitate the transfer of skills to local labour markets. While the notion and extent of brain drain are far less clear-cut than previously thought, there may nevertheless be a case for making work permits temporary, in order to ensure that the skills and savings are recycled back to countries of origin. A temporary work permit scheme could be combined with an EU pledge to reduce the costs of remittances sent back to sub-Saharan Africa to 3% from the current rate of above 9%,6 an objective also stipulated in the UN’s sustainable development goals. Given the importance of remittances in many of the main African source countries – accounting, for example, for more than 13% of Senegal’s GDP in 20167 – this could prove to be a valuable bargaining chip. Further concessions to African countries will have to be made to ensure cooperation, but they will require intense consultation with African governments to better understand their needs; a one size fits all approach will not suffice.

In its recent external pageCommunication on the delivery of the European Agenda on Migrationcall_made, the Commission is moving slowly in this direction by suggesting the launch of pilot schemes to facilitate legal migration and the use of available leverage to increase return rates to third countries. Since third-country access to EU labour markets is foremost a member state competence, the Commission has no work permits to promise on its own and hence must move cautiously in this area. In fact, member state governments must work proactively with the Commission concerning both asylum regulations and procedures as well as the facilitation of work permits. This is precisely what advocates of a better asylum and migration policy should be pushing for in their home countries.

As always in the area of migration, the devil is in the detail, and those need to be worked out more precisely by the European Commission, member states and African partners. Those who are fearful that this way forward will be too difficult or, more generally, are sceptical that anything can be done to limit the flow of so-called economic migrants should keep in mind that a return to the pre-summer status quo on the Mediterranean is not a realistic political option. But there is a counterfactual – and that is the easy solution that is currently being pursued.

Notes

1 See external pagestatisticscall_made published by the Italian Ministry of Interior, 4 October 2017.

2 “external pageItaly's deal to stem flow of people from Libya in danger of collapsecall_made”, The Guardian, 3 October 2017.

3 “external pageCentral Mediterranean Route: Commission proposes Action Plan to support Italy, reduce pressure and increase solidaritycall_made”, Press Release, European Commission, 4 July 2017.

4 See the external pageresultcall_made of a field survey conducted among Italian citizens by the Milan-based Institute for International Political Studies (IIPS), 26-27 September 2017.

5 See “external pageA Rome Plan for the Mediterranean migration crisis: The case for take-back realismcall_made”, ESI paper, European Stability Initiative, 20 June 2017.

6 See “external pageRemittance Prices Worldwidecall_made”, World Bank, Report No. 22, Washington, D.C., June 2017.

7 See the latest external pageestimatescall_made by the World Bank of personal remittances received (% of GDP).

About the Authors

Mikkel Barslund is a Research Fellow in Economy and Finance at Centre for European Policy and Strategy (CEPS).

Lars Ludolph is an Associate Researcher in Economy and Finance at CEPS.

Thumbnail external pageimagecall_made courtesy of Newtown graffiti/Flickr. (CC BY 2.0).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.