Rejecting Peace? Legacies of Violence in Colombia

8 Nov 2016

By Håvard Mokleiv Nygård and Michael Weintraub for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

This external pageConflict Trends 4/2016call_made was originally published by the external pagePeace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)call_made in October 2016.

On October 2, 2016, Colombians narrowly voted to reject the peace agreement negotiated between their government and the FARC, the country’s largest rebel group. While significant levels of abstention and a hurricane on the coast both contributed to the razor-thin victory for the “no” camp, past legacies of violence can help explain which communities supported the agreement and which did not.

Brief Points

- Communities heavily affected by guerrilla violence throughout the conflict tended to vote in favor of the peace agreement.

- The opposite pattern is evident for violence perpetrated by paramilitary groups.

- Poorer, more rural communities voted to ratify the peace accords.

- Urban areas tended to vote against the agreement.

Falling Short of Peace

Popular referendums to approve or reject civil war-ending peace agreements have been adopted in a number of countries as conflict parties seek to politically legitimate complex agreements. In a few cases, including in Guatemala and Cyprus, citizens ultimately opted to reject negotiated exits from war, producing uncertainty and confusion about popular commitments to peace.

On October 2, 2016, following four years of negotiations between the Colombian government and Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), the country’s largest and oldest rebel group, Colombian citizens were asked via a plebiscite whether they wished to accept or reject the final agreement. By a razor-thin margin, voters opted to reject the final agreement. What explains the decision by Colombian voters to reject the best hope for ending a five decades-long conflict?

Some point to the extremely high levels of abstention, with less than 40% of eligible those eligible casting their vote, due to apathy, to the fact that this was an unusual election that was not on the traditional election calendar, or to difficulties that voters on the Caribbean coast faced in reaching the polls due to the effects of Hurricane Matthew. Others point to failures of the campaign itself: claims of misinformation and lies on the part of the “no” campaign and claims of exaggerating the benefits of peace on the part of the “yes” campaign. These are certainly valid explanations, yet we lack hard evidence to be able to evaluate a number of these hypotheses.

Legacies of War

In this Policy Brief we assess whether legacies of the armed conflict, in addition to various sociodemographic and economic indicators, can help explain why some communities in Colombia voted in favor of ratifying the peace accords while others opted to reject the deal. To do so we take municipalities as our unit of analysis.

We use electoral data obtained at the municipal level from the Registraduría Nacional de Estado Civil, the governmental body that implements elections.

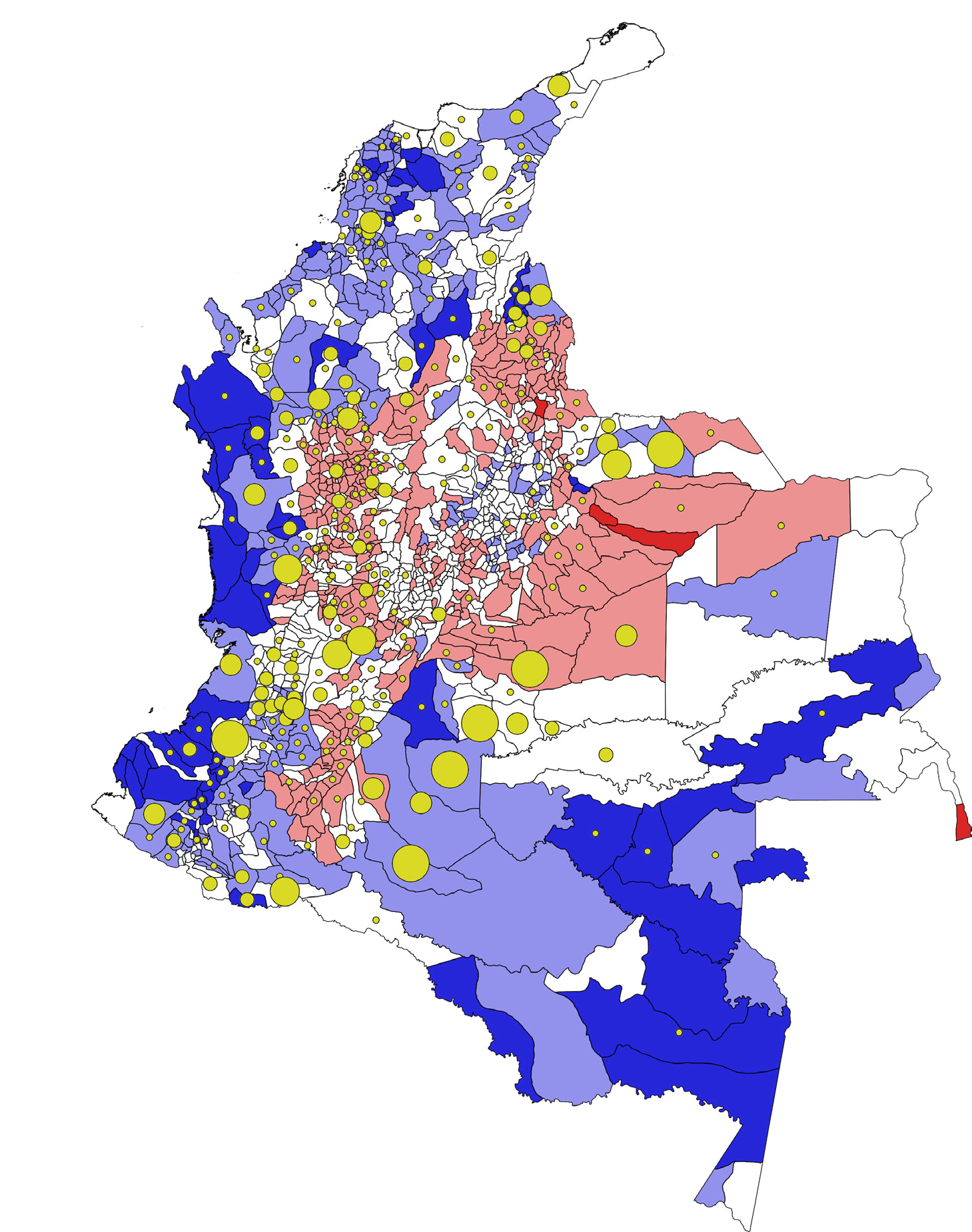

As the map in Figure 1 indicates, support for the agreement negotiated between the Colombian government and the FARC was primarily concentrated in peripheral regions of the country and along the coasts, while the central region (including Antioquia, home to Medellín and opposition leader ex-president Álvaro Uribe) voted to reject the deal. In the map, darker shades of blue indicate higher support for the agreement, white regions indicate rough parity of the vote, and darker shades of red indicate lower support.

We take our analysis further by combining the electoral data with data on violence taken from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s Georeferenced Event Dataset (UCDP GED) and the Human Rights Observatory Database, compiled by the Presidency of Colombia and based on daily bulletins internally compiled by the Colombian government’s security agency, including data on economic, political, and geographic factors (population size, rainfall, area of the municipality, distance from Bogotá, coca cultivation, royalties from natural resources, state presence, voting patterns in the 2014 presidential election, histories of different kinds of victimization by armed groups, poverty, and others). We estimate a set of statistical models, which seek to uncover why some municipalities voted for and others voted against the peace agreement, control for potential confounders that might affect both our chosen independent variables (such as past violence and poverty) and the dependent variable (percent of votes in a municipality that voted “yes”).

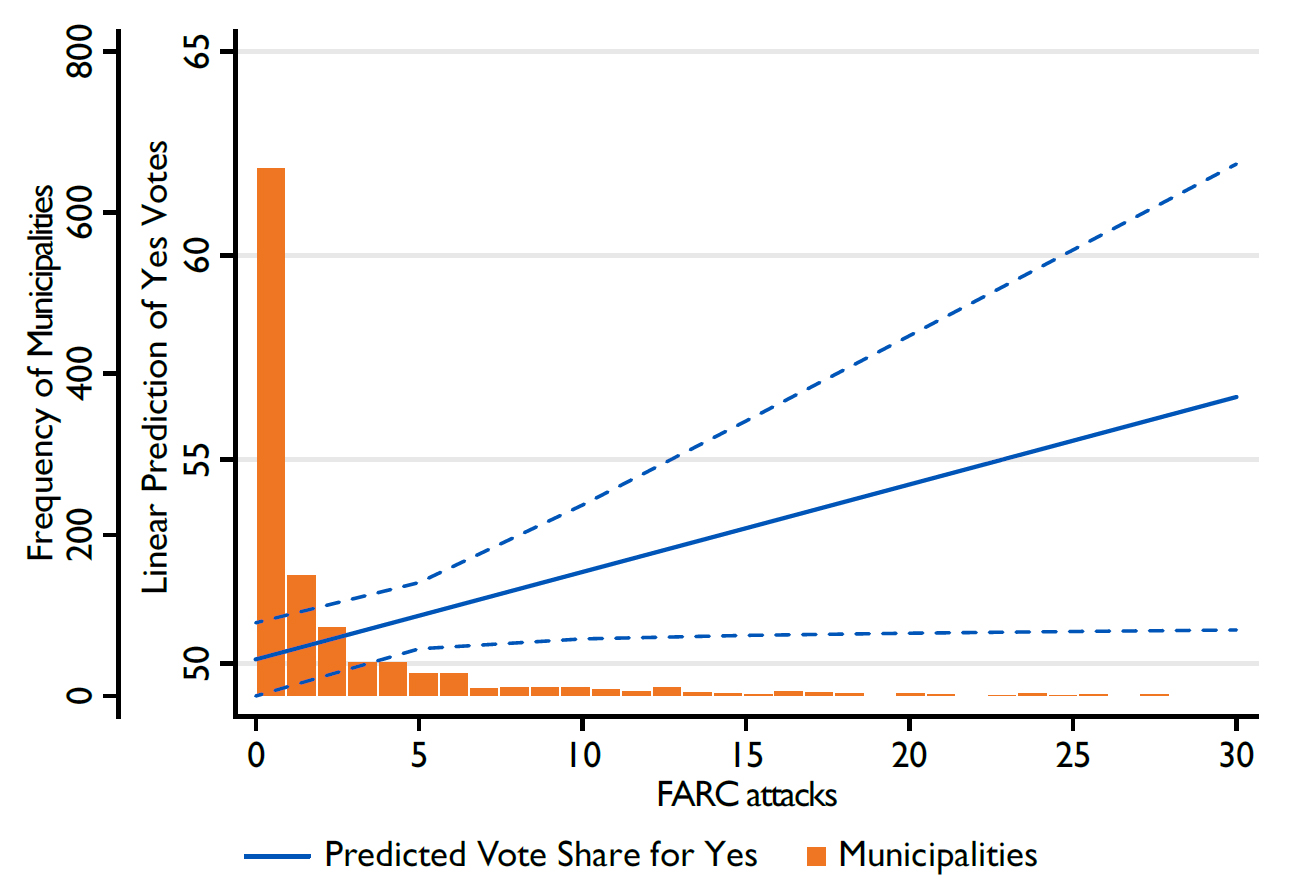

As we know from a large body of literature, victimization affects political behavior, including but not limited to decisions about citizens’ vote. We show that even after controlling for the factors mentioned above, the total number of FARC attacks perpetrated between 1988 and 2015 had an important effect on communities’ decisions about whether to support or reject the peace agreement. Communities that were not touched by FARC violence tended to vote no, whereas communities most heavily affected by FARC violence tended to vote yes.

As a first indication of this, in the map in Figure 1, we have added bubbles that are proportional in size to the number of battle-related deaths that UCDP GED have recorded in the district over the 2005-2015 period for all conflicts in the Colombia in the period. The UCDP GED measure of battle deaths are a conservative measure of victimization and only include direct battle deaths. This measure of victimizations therefore does not take into account the additional burden of conflict incurred through indirect deaths resulting from, for instance, a breakdown in state services, increased rates of poverty and hunger, and forced displacement.

Nevertheless, the map clearly indicates a relationship between battle deaths and the plebiscite vote. There appears to be a strong clustering of communities that have seen more battle deaths and communities with a higher degree of support for the peace agreement.

Using the longer data series of 1988–2015 on the number of FARC attacks in a community from the Human Rights Observatory Database, Figure 2 shows that for every additional FARC attack over this time period, we expect to see an additional 0.21 percentage point increase in yes votes in a given municipality.

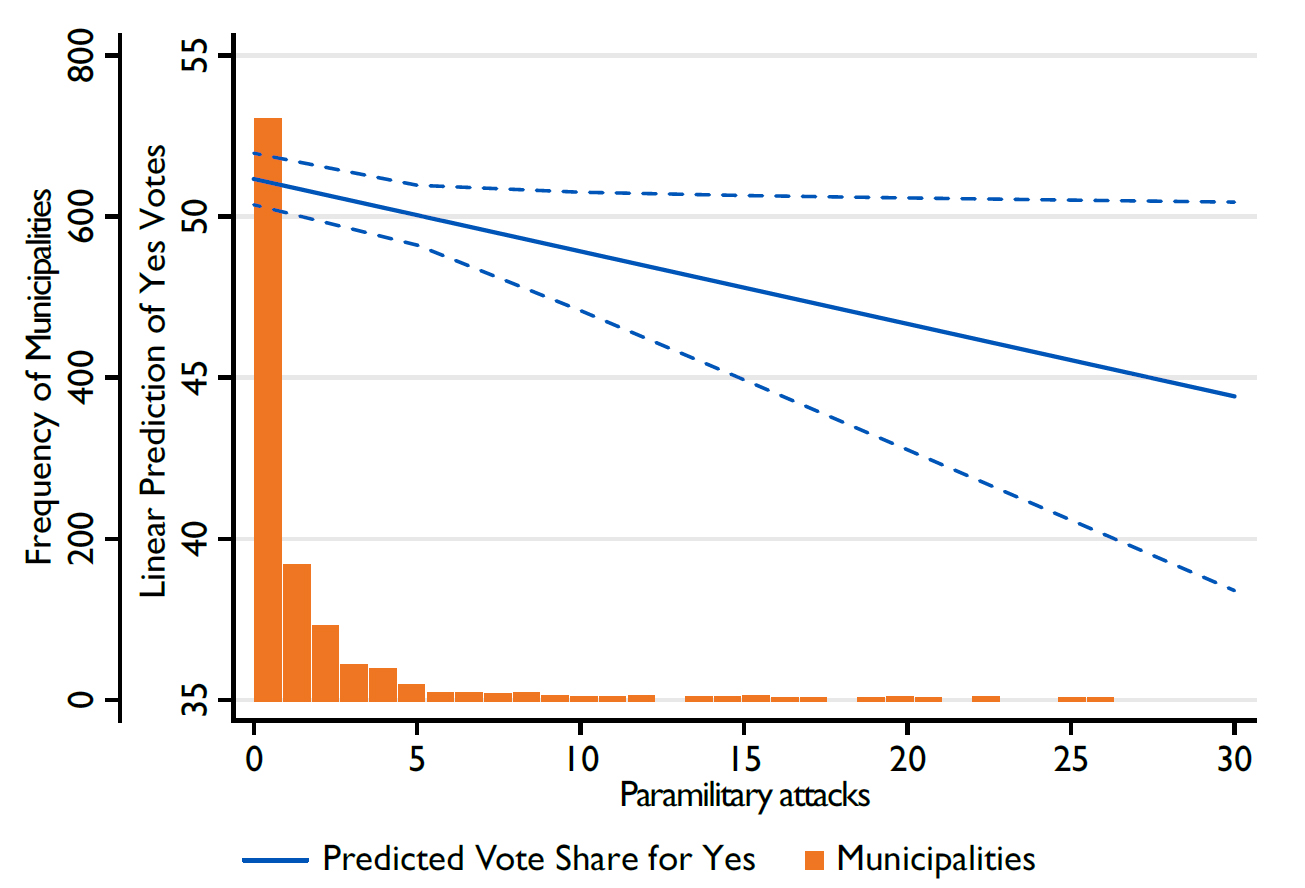

The opposite pattern holds for cumulative paramilitary attacks: communities where paramilitaries engaged in high levels of violence over this period were less likely to vote to ratify the peace deal. As seen in Figure 3, an additional attack between 1988 and 2015 likewise results in a reduction of .22 percentage points for the yes vote.

Direct attacks by guerilla and paramilitary forces by themselves do not come close to giving a complete picture of how Colombian communities have been victimized by the more than 50-year long conflict. Indeed, the consequences of armed conflict extend far beyond attacks and direct deaths in battle. Armed conflict often leads to forced migration, long-term refugee problems, and the destruction of infrastructure. Social, political, and economic institutions can be permanently damaged.

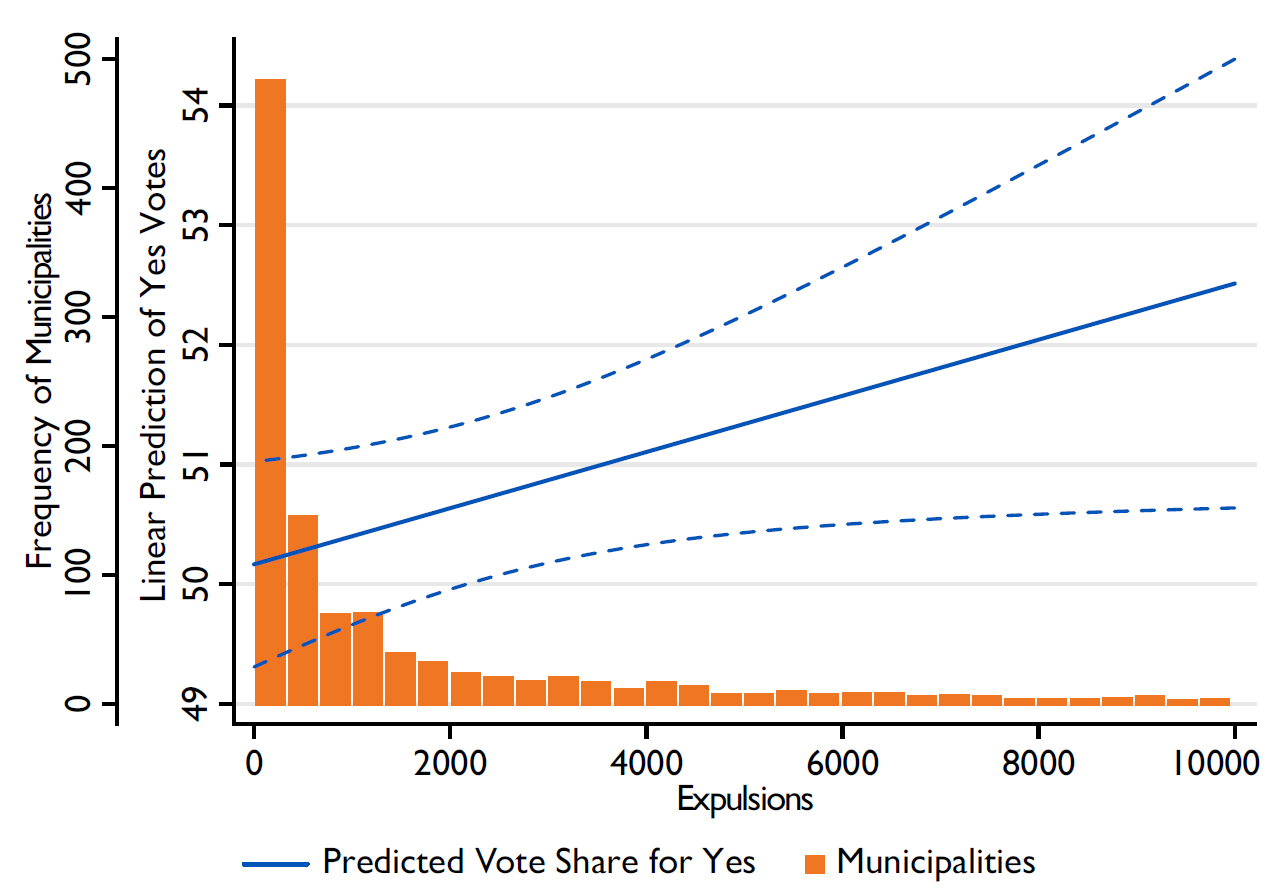

The conflict in Colombia is no exception. Forced displacements have been a grave problem for Colombia, with more than 7 million victims of this form of violence over the course of the conflict. A similar pattern as the one described above holds for forced displacements. Illustrating this, Figure 4 shows a strong tendency for communities to be much more favorable to the agreement if those same communities had experiences of forced displacement. More generally, both communities that have received large numbers of displaced persons and those that have seen large numbers of people expulsed were far more likely to vote in favor of the agreement than those that saw fewer displacements.

A Divided Society

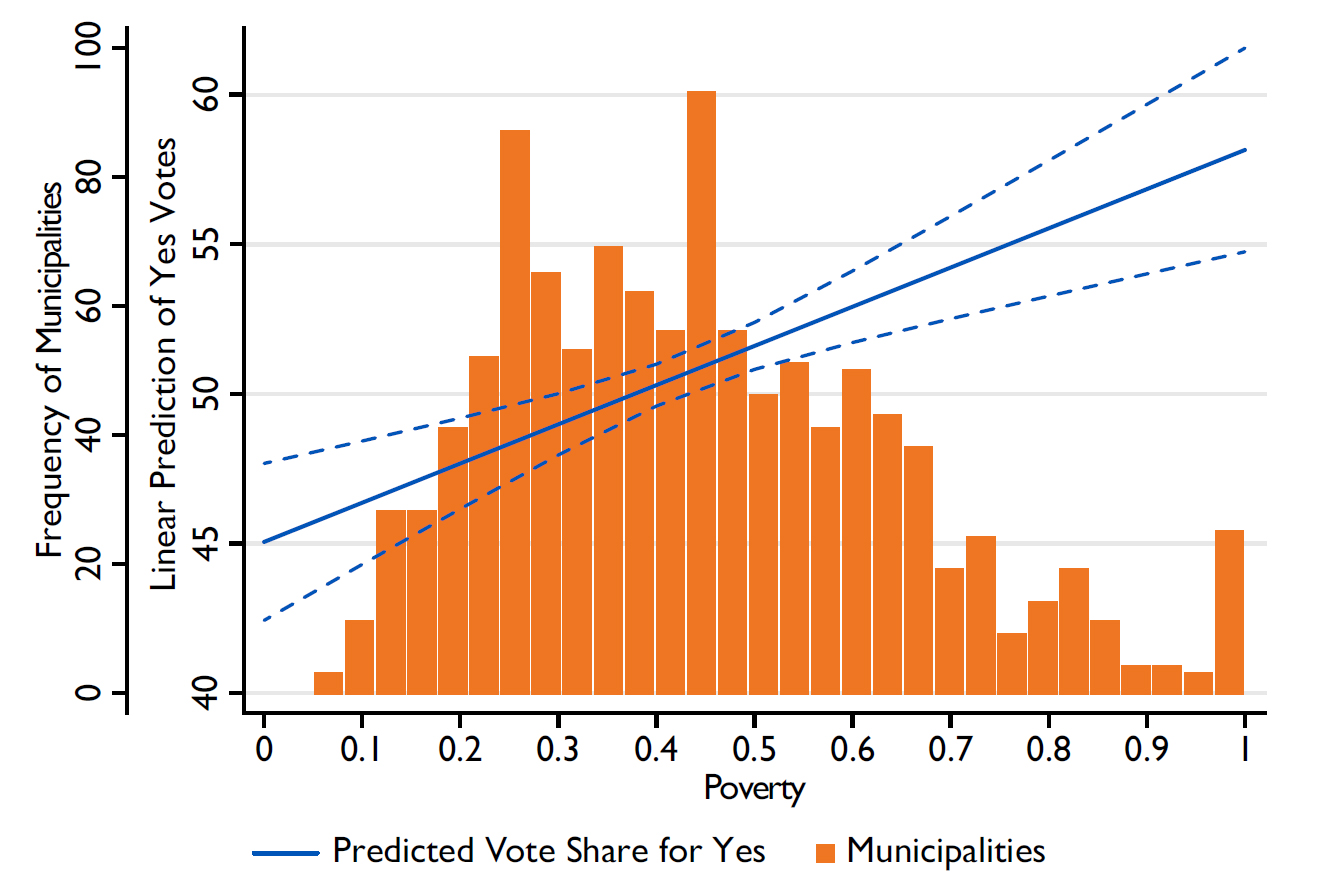

Underscoring the divided nature of Colombian society, economic factors also played a role in how communities voted in the plebiscite. As seen in Figure 5, poorer communities tended to vote more overwhelmingly in favor of the peace agreement than those that are comparatively more affluent. The figure uses the NBI index, a comprehensive measure of the extent to which individuals have unsatisfied basic needs, such as lack of access to clear water, education, and nutrition. The effect of poverty is easily on par with the effect of guerilla attacks. This may be because poorer communities were more likely to be affected by conflict and therefore sought to be free from violence, or because the peace agreement would have brought much-needed economic development to poor (especially rural) areas.

The results in the plebiscite also display a clear rural-urban divide: more populated municipalities and cities, which were comparatively less affected by FARC’s brand of guerrilla warfare, were much more likely to reject the agreement, while more sparsely populated areas tended to vote yes. A related measure, the municipality’s distance from the departmental capital, is likewise positively correlated with a “yes” vote: places further from each department’s capital were more likely to vote yes than those that are closer to regional economic and political hubs.

Finally, and perhaps unsurprisingly, a good predictor for the yes vote is the percent of residents who voted for President Juan Manuel Santos when he was running for reelection in the 2014 elections. That election was itself essentially a referendum on the wisdom of holding peace talks with the FARC.

The Way Forward

Based on this preliminary analysis of the determinants of the vote in Colombia’s peace plebiscite, in going forward the negotiators on both sides need to take into account the deeply divided nature of Colombian society. These divisions are particularly pronounced when examining communities’ legacies of violence. The irony is that while the narrative of punitive measures to ensure justice for victims mobilized “no” voters, those most affected by conflict voted in favour of the existing deal. All Colombians – those intimately affected by the war and those at some distance from it – have a duty to consider the costs of continuing the conflict, particularly for those who have traditionally been burdened by the human and economic costs of violence. Colombian society also deserves a more honest, transparent evaluation of the likely impact of the implementation of any future agreement. Given the open admission by the head of the “no” campaign that his camp relied on false information to increase turnout for the “no” side, it is imperative that politicians be held accountable for any misleading claims made regarding the likely ramifications of the accords.

No one can know if the political negotiations currently taking place between supporters of the “yes” and “no” camps will bear fruit, nor how the FARC will respond to the new proposals. What is clear is that the plebiscite revealed significant political and economic divisions in Colombian society. The rural/urban divide, the bifurcation between communities that have had to bear the brunt of the armed conflict and those that have not, the gulf between wealthier and poorer communities, all clearly help explain differences in attitudes towards the peace deal that was voted down on October 2. What remains to be seen is whether provisions in the agreement that ensure access to land for Colombia’s poorest and provide significant investments in rural infrastructure will survive, helping to close some of these divides and moving Colombia towards a more inclusive, equitable future.

About the Authors

Håvard Mokleiv Nygård is Senior Researcher at PRIO. His research focuses on the political economy of violence and social order. Michael Weintraub is Associate Professor at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. His research interests include political violence in civil war, criminal violence in weak democracies, electoral mechanisms in divided societies, and state-building.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.