The Strategic Risks of East Asia´s Slowing Economies

4 Sep 2017

By Tim Johnston for Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageAustralian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI)call_made on 24 August 2017.

Introduction

After half a century of almost uninterrupted economic growth, we have largely forgotten to factor in the potential impact of sustained economic weakness when analysing geopolitical risk.

Global economic growth has slowed substantially since the heady days before the financial crisis of 2008. The advanced Western economies have barely recovered, and, after decades of average growth of 10% in China, Beijing says the Chinese economy is now expanding at 6.7%— a figure many external analysts believe is optimistic. There’s little sign of a return to pre-financial-crisis growth rates any time soon.

The potential dangers of a prolonged economic trough are global, but in East Asia many governments depend on their ability to deliver economic growth either to fulfil election promises, in the case of the democracies, or to justify their continued monopoly on power, in the case of the autocracies.

The threat of economic weakness stokes primal, Maslovian fears of insecurity, undermining moderate narratives and opening the door to the politics of social and religious chauvinism. The misguided but pervasive Western narratives of migrants ‘stealing’ jobs and welfare are directly linked to this phenomenon, and similar appeals to divisive tribal instincts can increasingly be seen in the pitches of populist politicians across East Asia.

The danger isn’t just that moderates will be unseated by populists who prey on the fears of their constituents, but that moderates will feel forced to follow the populists down the road of demagoguery to retain relevance, as we have seen in Malaysia and elsewhere in recent years. This dynamic constitutes a major vulnerability at a time when slowing regional and global growth is combined with growing strategic uncertainty.

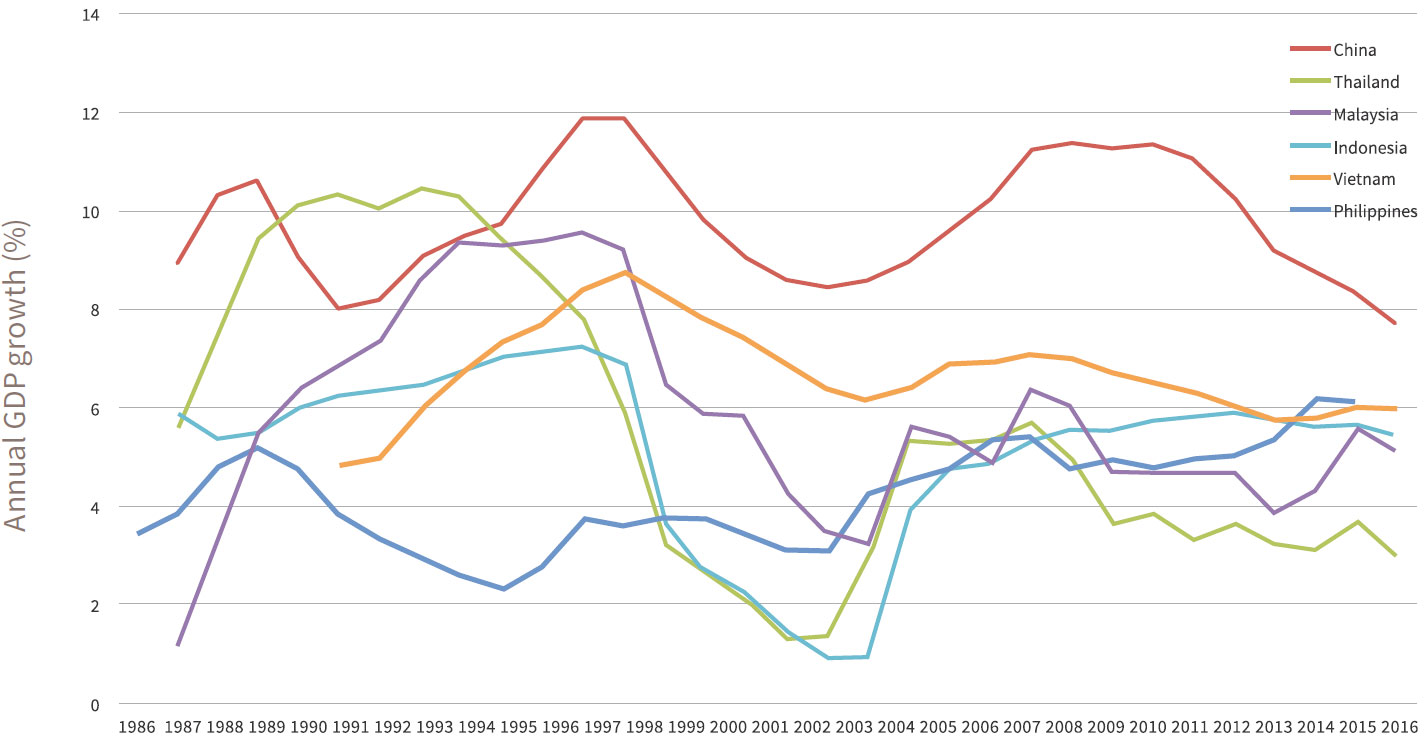

Of the six major developing economies of East Asia (China, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines), in 2016 the Philippines was the only one of the six major developing economies of East Asia to grow faster than its 30-year average—a period that includes the devastation of the 1998–99 Asian financial crisis (Figure 1). The economic slowdown and the political problems it will create will strain the social fabric within East Asian nations and put pressure on the relations between them.

Figure 1: Economic growth, China and ASEAN-5, 1986 to 2016

The traditional view of the link between economics and security

The study of the impact of security, or lack of it, on economic performance has generated an extensive literature. The damage that insecurity, let alone conflict, can do to the economy is clear. The impact of prosperity, or the lack of it, on security has received less attention, except in either the narrow historical sense of economic power enabling military power or in the sense that high levels of extreme poverty can provoke insecurity.

When economies are growing, internal security tends to improve as dissent is placated by potential and actual improvements in standards of living and the extra freedom of choice that comes with economic empowerment, and external security tends to improve as greater prosperity boosts defensive capacity, increasing the potential cost to any aggressor.

East Asia has little prospect of an imminent return to high unemployment or a rapid rise in poverty on any scale, but it isn’t safe to assume that the relationship that exists between prosperity and security in a growing economy will remain the same if and when growth begins to slow significantly. A small decline in prosperity might lead to a significant rise in the risk of conflict.

Research using rainfall variation as a proxy for income shocks in 41 African countries found that a decline in economic growth of 5 percentage points increases the likelihood of conflict by 50% the following year.1 The impact of economic insecurity can also be seen in places such as the US rust belt and the post-industrial cities of northern Europe, where support for exclusionary and divisive politics has grown significantly in recent years, spurred by narratives of social fear built around the reality of economic decline.

Four decades of breakneck growth in East Asia have created new expectations, particularly among the current and aspirational middle classes. Sociologists argue that conflict can stem from ‘relative deprivation’, specifically when expectations of improved social or economic status are thwarted.2 Those changed expectations mean that, when it comes to social discontent, a change in the direction of growth isn’t like reversing the film in a projector: there’s unlikely to be a return to the status quo ante. This is particularly true in East Asia, where rapid urbanisation over the past four decades has both reduced the ability to fall back on agriculture during hard times and created potential pools of restive disaffection among the urban unemployed.

Samuel Huntington argued that rising prosperity brings greater involvement in national politics and that tensions emerge as established political institutions struggle to adapt to rising demands.3 This phenomenon is clearly visible in places such as Thailand and Malaysia, where the elites that managed the economic transformation from the 1960s on have refused to relinquish the commanding heights of politics and the economy in favour of a broader franchise.

Arguably, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has adapted more successfully than most through its adoption of key characteristics of a market economy, but the current re-establishment of Party influence under President Xi Jinping and the reimposition of extensive social and economic controls may indicate that Dengist ideological flexibility has reached its limit. This potentially sets the stage for frustrated expectations, denied the salve of continuing rapid economic growth, to find expression in social unrest, or to persuade the government to funnel domestic discontent into overseas conflicts.

The problem of performance legitimacy

In the common Western conception, government legitimacy is determined predominantly through the degree of procedural democracy and participation (sometimes called ‘input legitimacy’). This isn’t particularly useful as an analytical tool in the context of East Asia, where the underpinnings of democracy have been eroded in recent years despite varying levels of commitment to the trappings of democratic process, such as elections.

Across East Asia, governmental legitimacy rests less on votes or participation than on the government’s ability to deliver public benefits to the population, and in most cases it rests specifically on the ability to deliver continuing economic growth. The importance of performance legitimacy can be measured by the prominence it’s accorded in the Constitution of the CCP:

The general starting point and criterion for judging all the Party’s work should be how it benefits development of the productive forces in China’s socialist society, adds to the overall strength of socialist China and improves the people’s living standards.4

When the global economy was growing strongly and the regional economy was reaping outsize rewards from first-phase industrialisation, this narrow focus on performance legitimacy (also known as ‘output legitimacy’) was not a problem. The social contract was modified to limit certain rights—typically, the ability to challenge policies that were seen to boost the economy regardless of their social, cultural or environmental cost—in return for growth.

It was a bargain many East Asians seemed happy to make. Since the 1980s, there has been little widespread social protest against the authoritarian policies of many governments, not least because they used the fruits of growth to provide rents for constituencies that could otherwise have proved troublesome. As growth slows, there’ll be less money to buy off troublesome constituencies or powerful politicians.

Performance legitimacy is an inverted pyramid: a great deal rides on a single point. The perils of seeking legitimacy based on a narrow ability to deliver growth are clear. Indonesia’s President Suharto was overthrown in 1998 in an uprising that was triggered by the fallout from the Krismon—the Asian financial crisis—and his inability to maintain key subsidies, particularly those on fuel.

An over-reliance on performance legitimacy also promotes an unhealthy symbiotic relationship between a country’s political and business elites, drawing them closer and encouraging crony capitalism by giving it a veneer of both economic and political respectability. It’s notable that most countries in East Asia have de facto if not de jure gravitated towards—or reverted to— economic policies that are indistinguishable from the largely discredited ‘trickle-down’ theory of economic growth. Data gathered by Cielito Habito, a former planning minister in the Philippines, indicated that in 2011 the 40 richest Filipino families on the Forbes Rich List accounted for 76% of GDP growth.5

If the ruling elites in East Asia can’t fulfil their side of the bargain by delivering growth because the global and regional economies are mired in a prolonged slowdown, the deal with their peoples risks breaking down.

This poses particular problems for foreign investors. The blurring of the lines between the political and economic elites means that any anger of the politically dispossessed is just as likely to be aimed at economic targets as at political figures and institutions.

The economic climate in East Asia is deteriorating

Although there’s no clear indication that East Asia is heading for an economic meltdown at a speed and on a scale similar to 1997— Thailand’s GDP shrank by 10% in 1998—growth in the region is slowing.

The World Bank estimates that growth in developing East Asia will be 5.8% this year and 5.7% in 2018. If China’s questionable data is excluded, the World Bank predicts growth of 4.8% in 2017 and 5.1% in 2018, but the bank warns that ‘the global environment and domestic vulnerabilities still pose risks to the region’s prospects’.6

Even if these forecasts are correct and the combination of the systemic shock delivered by Donald Trump’s election and rising interest rates in the US do not further depress investment and growth in East Asia, this is substantially below the breakneck rates of the 1990–1995 period, when Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam (which between them account for two-thirds of the population of ASEAN) averaged 8.5% per annum, or the 2000–2005 period, when the same four countries grew at an average of 5.6% (refer back to Figure 1).7

China’s economy is slowing as Beijing tries to switch from an investment-led model to consumption-led growth, but debt levels are still growing as the authorities attempt to prevent a hard landing. The official growth rate was 6.7% in 2016—the lowest in 26 years—but many economists believe the real rate is already below 5% and falling. The risks to China’s economy are discussed in more detail below.

It’s hard to overemphasise how dependent East Asia is on the health of the Chinese economy. In the decade between 2004 and 2014, ASEAN’s trade with China tripled to account for 15% of overall trade.8 But that figure fails to tell the full story. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that a fall of 1 percentage point in China’s growth translates into a fall of between 0.2 and 0.5 percentage points in the five largest ASEAN economies.9

There are other threats to growth. Economic nationalism, including trade protectionism, is rising globally, and East Asia is no exception. The current problems of US-owned Freeport-McMoRan in Indonesia—a political movement to nationalise the company, which mined $3.1 billion worth of copper and gold in 2015, is supported by key members of President Joko Widodo’s supposedly pro-business government and is gaining strength10—are emblematic of a region that not only feels more confident when dealing with foreign investors, but is also looking for soft foreign targets to boost the bottom line as its economies slow.

East Asia, which is more dependent on global supply chains for economic growth than many other regions, has resisted calls for trade protectionism within the region, but is still vulnerable to nationalist movements in the US and Europe, which together accounted for 32% of Asia’s trade in 2014,11 and elsewhere.

Finally, East Asia is seeing a sharp rise in inequality, particularly in the large Asian emerging markets. Although the poverty rate in Asia fell from 55% in 1990 to 21% in 2010, the Gini coefficient rose from 37 to 48 on a population-weighted basis between 1990 and 2014, according to the IMF.12 The World Bank considers anything over 40 as alarming in terms of social stability, although that figure has been challenged as arbitrary.

In the same paper, published in March 2016, the IMF said that ‘inequality can weaken the support for growth-enhancing reforms and may spur governments to adopt populist policies and increase the risk of political instability’. It can also prompt governments to repress restive populations. The relationship between inequality and conflict is problematic. Many early analyses were based on the tenuous assumption that poor people were more prone to violence—an assumption that’s countered by the prolonged existence of deeply unequal societies that don’t descend into conflict.13 However, although inequality on its own may not be a sufficient condition for social conflict, it has been a key part of the narrative of almost every uprising in East Asia since World War II.

National and international institutions that might act as social shock absorbers have been hollowed out

Conflict thrives when states are weak either internally or externally, and states are vulnerable to both outside pressure and internal dissent in a world of declining economic growth and weakening performance legitimacy. Governments in East Asia have pursued economic growth with a single-minded focus that has weakened key social and regional institutions that might have absorbed some of the anger that’s likely to be generated as economic circumstances decline.

Across the region, the mechanics of democracy, the independence of the judiciary, freedom of speech and the impartiality of the police, all of which should have roles in mediating the relationship between the populace and the government, have been degraded or were non-existent in the first place.

Robert Zoellick, the former president of the World Bank, says:

When state institutions do not adequately protect citizens, guard against corruption, or provide access to justice; when markets do not provide job opportunities; or when communities have lost social cohesion—the likelihood of violent conflict increases.14

Other researchers go further, suggesting that violent extremists are more likely to come from countries that lack civil liberties—a pressing concern in East Asia.15

The ability of East Asians to change their governments by exercising their democratic franchise is diminishing. In some countries, including China, Brunei, Laos and Vietnam, the people have never had the right to choose their government. In Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand, participatory democracy has been severely curtailed, and in all these cases the governments have justified their abridgement of democratic rights, at least in part, by citing the need for stability and continuity to ensure continuing economic growth.

James Fearon, who has studied conflict extensively, says ‘civil war somewhat reliably follows institutional changes in the direction of greater democracy or greater autocracy.’16 Even in Indonesia and the Philippines, where there have been reasonably successful democratic transitions in the recent past, the machinery of democracy remains hobbled by powerful unofficial patronage networks. Although he started as an outsider, Indonesian President Joko Widodo struggled to escape the influence of former president Megawati Sukarnoputri and has come to an understanding with the Golkar party—an organisation that was for decades President Suharto’s vehicle of political power.17 Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, supposedly an anti-establishment iconoclast, received immeasurable help from the Marcos family, who helped him win in their Ilocos Norte heartland, and the Macapagal family, whose backing enabled him to win Pampanga, among others.18

As a result of this erosion of key institutions, there remain few legitimate outlets for anger and resentment. For the moment, discontent hasn’t coalesced sustainably, or when it has—as in Thailand in 2010—the authorities were able to suppress the anger, albeit at the cost of internationally condemned bloodshed. But if that anger finds a cause and focal point and reaches critical mass, the institutions that should provide a way to change the system or provide redress peaceably will have been weakened to the point of uselessness. The only remaining outlet for the anger will be the streets.

Slowing growth, rising economic nationalism and growing inequality are interlinked and self-reinforcing

The dismantling of trade barriers over the past 50 years correlates strongly with rising prosperity, and it’s notable that as growth has slowed so has progress on opening up trade.19 When economies are shrinking, elites are less inclined to share their rents, as evidenced by the current growing inequality across the region in a time of slowing growth,20 and populations are more willing to tolerate restrictions on social and political freedom as a quid pro quo for future prosperity.

When growth slows or goes into reverse, these trends not only become harder to maintain, but tend to amplify each other. For example, governments have been more reluctant to lift trade restrictions on the slowest moving parts of their economies, particularly agriculture, and expose key constituencies to competition from more efficient producers.

During times of slow growth, governments—encouraged by rising economic nationalism on the streets—tend to clamp down to protect existing industries, rather than opening up in the hope of establishing new sources of growth.21 The progress of the ambitious ASEAN Economic Community is a case in point. The outline of the community was established in 2007 to realise ‘the goal of ASEAN as an integrated economic region by 2015’. For the first few years, the process went well, with average tariffs falling from 3.64% in 2000 to 0.05% by the end of 2011.22 But since then progress has slowed markedly in key areas such as the trade in agricultural goods, particularly rice and other staples, and the free movement of labour remains a distant aspiration.

Expectations of growth have provided a kind of social glue that has held societies together and validated a truncated social contract. As growth slows, governments frequently try to promote social cohesion by identifying ‘enemies’—either internal constituencies, such as the Jews in Germany in the 1930s, or external threats from other countries.

There’s a surfeit of research on how inequality does—or does not—affect growth, but little literature on how growth or lack of it affects inequality. Among those who posit a causal relationship between growing inequality and slowing growth, it has most often been assumed to be one-way—inequality slows growth—but there is an argument to be made from much of the same data that slowing growth can amplify inequality. The details of this argument are beyond the scope of this paper, but it’s reasonable to assume that political and economic elites look to protect their rents as GDP growth slows, further exacerbating inequality and alienation. In societies where the political and economic elites are closely allied, such as most of those in East Asia, this phenomenon is likely to be amplified.

Development aid and security

International donors, including Australia, have based much of their aid-giving policies on the assumption of a strong link between economic development and security. There’s little disagreement that insecurity has a negative effect on development and growth more broadly, as it destroys infrastructure, deters investment, uproots populations and sucks resources out of the non-war economy.

There’s also broad agreement that low levels of development can increase the risk of conflict. ‘Poor development plays a key role in that it creates masses of people with few alternatives—people with essentially zero opportunity costs—who become natural recruits for a rebel group,’ as Professor David Gold of the New School University put it.23

East Asia as a whole is relatively well developed economically, to the extent that classic economic development aid is neither badly needed nor likely to have a significant impact. More useful would be aid that boosts key institutions to improve equal access to security, justice and jobs, although Western donors have frequently struggled to see beyond reproducing facsimiles of their own institutions in foreign lands.

The downside of interconnectivity

Globalisation has been a boon to East Asia. The combination of cheap transport, vastly improved logistics and a relatively unrestricted global free trade system has lifted hundreds of millions of East Asians out of poverty while spinning a spider’s web of supply-chain connectivity that has drawn countries closer together.

While regional economies were growing, these products of globalisation were seen as benefits that linked the prosperity of one country to another’s and so contributed to stability, but in a slowing economy they could turn out to be liabilities. The supply chains that once spread wealth become the transmission lines for economic shock; the internet, which allowed producers to find buyers, becomes a dissemination system for the corrosive ideas of social or religious radicals; and the shared economic networks guarantee that any economic pain will be shared as widely as the benefits.

In 2015, 51% of Asia’s exports were within Asia,24 and the ratio of imported intermediate goods—part manufactures that are assembled elsewhere—to total exports was also 51%.25 Although export growth is no longer the economic driver that it was before the 2008 crisis, this data speaks of a worrying level of co-dependency among Asian economies.

Much of the growth in East Asia over the past decade has derived not from growth in demand but from the optimisation of production processes. This has made intra-regional trade more efficient, but also more vulnerable. The Fukushima earthquake and floods in Thailand’s industrial heartland, both in 2011, showed how relatively localised disruptions could create ever-widening arcs of disruption. For example, the destruction of a single factory near Fukushima, which made a unique automotive paint additive, forced carmakers including Ford, Chrysler, BMW, Toyota and General Motors to restrict orders and scramble to find a replacement.26 Automakers and other multinationals have moved to build extra redundancy into their supply chains since 2011 to prevent a recurrence of such disruption, but smaller Asian companies don’t have that luxury.

It’s easy to use supply-chain dependency as a weapon. If, as surmised above, an economic slowdown will empower chauvinist nationalists, it’s not a great leap of imagination to assume that they could move beyond trade protectionism to weaponising trade for political and diplomatic ends. In some ways, this is already evident in the recent losses that Korean exporters to China have suffered in the wake of the decision to deploy the Terminal High-Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) system in South Korea.27 To a much greater extent than the US, China clearly sees its economic power as a natural extension of its strategic planning and imposes costs for noncompliance. In the seven years between 2006 and 2013, China invested some US$33 billion in the 10 ASEAN states. Over the same period, net Chinese investment in the Philippines, an ASEAN member with which Beijing has had a tempestuous relationship over islands in the South China Sea, was minus US$1 million, although it has increased since President Duterte went to Beijing and promised not to press the issue of the South China Sea.28

Growing economic co-dependency also presents an analytical problem beyond the strategic risk. David Ricardo and Adam Smith both argued that economic cooperation reduces the likelihood of war by increasing the benefits of collaboration or, at a minimum, non-confrontation. But the potential sources of friction in Asia—border disputes, ethnic tensions, rising nationalism, among others—have not disappeared. Should these dynamics start to produce significant friction, it will be in governments’ interest to underplay them to avoid upsetting trade links, making it harder for analysts to predict confrontation and for policymakers to head it off.

Moving closer to conflict

In a speech in 2008, Robert Zoellick, then president of the World Bank, identified one of the key strategic risks in a globalised age. ‘(F)ragile states can create fragile regions,’ he told the International Institute for Strategic Studies.29

East Asia as a whole looks stable, but its governments’ continuing reliance on performance legitimacy in an era of prolonged economic weakness has weakened the social contract internally, and economic co-dependency has regionalised the external risks.

In most analyses, the middle class is seen as an anchor of stability, and boosting the size of the middle class as the best way to cement democracy and stability. But a middle class that feels that it’s been betrayed, or feels that its hold on prosperity is under threat from factors it can’t control, or a working class that feels the dream of acquiring middle class status slipping beyond its grasp, could quickly become a source of instability.

The middle classes have a long history of moving against the status quo when conditions become adverse. It’s notable that, despite the media focus on the working class whites who voted for Donald Trump, only 39% of college-educated white males voted for Hillary Clinton;30 and in Britain, 55% of those who voted for Brexit owned their houses outright.31 Closer to home, the strongest support for the coups in Thailand since 2006 has come from the middle-class ‘yellow shirts’; and President Rodrigo Duterte was the most popular choice among the Philippines middle class: ‘It is the angry protest of the new middle class,’ as political scientist Julio Teehankee said of support for Duterte.32

An angry and disoriented middle class is already opening the door for iconoclasts who, unable to achieve legitimacy through economic growth, are being forced to resort to populism. Duterte has concentrated on drugs; in Indonesia, the Gerindra party of Prabowo Subianto, a former general and son-in-law of President Suharto who has been accused of ordering the murder of dissidents, ran a successful but divisive religion-focused campaign against the incumbent (Christian) governor of Jakarta. That chauvinist approach echoes the divide-and-rule policies of Prime Minister Najib Razak of Malaysia; and in Thailand the government led by General Prayuth Chan-Ocha has curbed freedoms and is promoting a vision of ‘Thai-ness’ that stresses obedience to authority, while buying off rice farmers, a traditional source of protest, with cheap loans.33

The factors linking all these countries are that democratic norms are being challenged and that they are led by men whose outlook is more nationalist than internationalist. ASEAN—not a proactive organisation at the best of times—is stumbling along, hobbled by a seeming lack of interest from leaders such as Duterte and Widodo and fragmented by pressure from China.

The seeds of conflict already exist. Almost all East Asian nations have border issues of one kind or another with their neighbours.34 It’s noticeable that when border disputes flare (Cambodia–Thailand, 2008; Philippines–Malaysia, 2013; Cambodia–Vietnam, 2014; et al.), they often seem to be tactical attempts to deflect domestic pressure on one side of the border or the other. Malaysia’s opportunistic criticism of Myanmar over Naypyidaw’s treatment of the Rohingya, which happened as the government was under considerable domestic pressure, illustrates how fragile the commitment to regional solidarity is when domestic pressures grow.

The South China Sea disputes don’t fit neatly into this category, as China has significant strategic military interest in ensuring that its second-strike capability submarines can exit the sea from their base in Hainan without detection. But here, too, Beijing’s controversial maritime expansion has coincided with a time when the economy is slowing and the nationalist lobby within China has been gaining traction, if only in relative terms, as other once-powerful constituencies are felled under the axe of the anti-corruption campaign.

The political atmosphere in East Asia has been made more febrile by a generational shift in power as a younger demographic empowered by economic choice seeks greater control over its destiny, frequently provoking the sort of reactions we’ve seen in Thailand and Malaysia. In China, the post-Mao Dengist policy of elite consensus rule is breaking down, and not just because it’s under assault from Xi Jinping. In Thailand and Malaysia, an old guard is desperately trying to hold the line against an electorate that has outgrown the paternalism that delivered the success of first-phase industrialisation. The Philippines is flirting with the prospect of breaking away from the oligarchy of powerful families that has dominated politics since World War II. Even in Cambodia, Hun Sen’s 38-year hold on power seems to be slipping.

Fragile states have always been able to create fragile regions, but the risk is enhanced in a highly connected region such as East Asia. Supply chains become shock-transmission mechanisms, potentially infecting all with economic malaise where they once spread the fruits of economic growth. An alienated middle class, or would-be middle class, combined with a slew of political systems that are in transition, makes for a fissile mix.

The relationship between prosperity and terrorism

In most Western analysis, there’s an assumption that there’s a link between poverty and terrorism. As Graeme Blair et al. put it in their paper, ‘Poverty and support for militant politics’:

[P]olicies intended to combat militant violence have focused on using aid to reduce poverty and move people into the middle class. Underlying this approach is the assumption that the correlation between poverty and support for militant politics is sufficiently strong that changes in income achieved through external aid will have a meaningful impact on support forviolent groups.35

But Blair’s research in Pakistan found that there was significantly less support for militant groups among poor people—particularly the urban poor—or people living in poor areas than there was among the middle class. This supports research elsewhere that indicates that participants in terrorist activities seem to be better educated and come from a higher income bracket than the bulk of the populations from which they are drawn.36 These findings support the thesis outlined elsewhere in this paper—that, under the right circumstances, the middle class can be a destabilising radical influence—and destroy the myth that middle-income countries are structurally immune to terrorism.

Over and above the issue of poverty, economics can have a powerful indirect effect on the risk of terrorism. ‘Poor development plays a key role in that it creates masses of people with few alternatives—people with essentially zero opportunity costs—who become natural recruits for a rebel group,’ as David Gold puts it in his paper, ‘Economics of Terrorism’.37 Economic exclusion can also provoke resentments that coalesce around apocalyptic ideologies.

Research by the International Crisis Group indicates that violent extremists more often exploit disorder than create it.38 This observation raises the question of ‘What is it that creates disorder?’ Although terrorism can originate from any quarter, the most proximate risk in East Asia comes from local groups adopting the global jihadist ideology of Islamic State, al-Qaeda, or both.

East Asia is host to four insurgencies by Muslim populations: in Xinjiang in China, Rakhine in Myanmar, southern Thailand and the southern Philippines.39 All four areas share certain characteristics. They are all home to economically and socially disadvantaged populations: even if the benefits of the past four decades of economic growth haven’t entirely passed them by, they haven’t shared fully in the new prosperity. Their people are all minorities, and thus easy pickings for populist nationalists looking to deflect criticism for mediocre economic performance by identifying a constituency to blame for society’s ills.

And they are all in the cross-hairs of international jihadists such as ISIS and al-Qaeda. During their expansion through North Africa, both groups have proved adept at reframing their religious metanarrative to incorporate local grievances about economic exclusion and other slights to draw pre-existing groups, such as al-Shabaab and Boko Haram, into their orbit. As Olivier Roy puts it, the global trend is less the radicalisation of Islam and more the Islamicisation of radicalism,40 and the more cause Asia’s Muslim populations have to be radicalised, the deeper the inroads that radical Islam will make into the region.

Indonesia, although vulnerable to terrorism in many other ways, is probably the regional country that’s the best insulated against the indirect economic drivers of extremism, because the bulk of its economic growth is derived from domestic consumption rather than exports. However, Jemaah Islamiyah is rebuilding its networks in Indonesia, and organisations such as Front Pembela Islam and Hizb ut-Tahrir,41 both well-organised hardline Sunni groups that operate on the murky frontier between legitimate political activity and violent extremism, could provide a lightning rod to guide middle-class ennui into more violent channels.

As a footnote, it’s also worth noting that adverse economic conditions make it harder to achieve peace. ‘Groups join or instigate rebellions for a variety of reasons, but an important body of research suggests that many rebel groups continue (and sometimes increase) their violent activities in the pursuit of economic gain,’ notes David Gold, an economics professor at the New School University in the US.42

The changing strategic environment

The East Asian strategic landscape is being reshaped by three forces. A resurgent China with both the will and the resources to lay claim to be primus inter pares, or more, in Asia; an ongoing reassessment within the US of its role in the world; and the exhaustion of the economic model that has delivered unprecedented regional growth over the past four decades.

Among China’s more powerful motivating forces is a sense of regional manifest destiny, although it differs from the American paradigm by being driven by a desire to erase the ‘century of humiliation’ and re-establish the regional and global superpower status that China enjoyed until about 1830. This vein runs deeply through Xi Jinping’s thinking, from the China Dream, to the ‘new model of major country relationship’,43 to One Belt One Road. But this vision has also empowered domestic nationalists, who have stepped into the vacuum created by the emasculation of powerful networks within the bureaucracy, state-owned enterprises and the People’s Liberation Army by Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. Nationalist ire is often expressed in economic terms: Japanese carmakers were boycotted when the issue of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea flared up, and South Korean retailers have been hit after Seoul agreed to station US-made THAAD systems on its territory.

China’s GDP is a little over four times the combined output of the 10 ASEAN members, but this in itself wouldn’t be sufficient to alter Asia’s strategic landscape without a willingness by Beijing to use its economic heft to achieve unrelated political and diplomatic ends. As seen in the case of the Philippines, China regards its economic power as a strategic tool, granting or denying favours depending on the level of cooperation.

In its Asia–Pacific security White Paper published in January, China advocates ‘a security framework which is orientated to the future, accords with regional realities and meets all parties’ needs.’44 It’s unclear how Beijing’s ‘realities’ will fit with those of other regional countries, particularly in the South China Sea. As just one example, China has a legitimate need to develop a bluewater naval capacity, but it will be of questionable use unless Beijing can establish secure routes between its territory—particularly its submarine base in Hainan—and the Pacific, although that would involve annexing large parts of the South China Sea.

China is in part filling a void left by the US. For years, the foundation stone of Washington’s relationship with its Southeast Asian allies was a promise that the US was a long-term strategic presence that could counterbalance China’s overwhelming geographic presence. President Obama’s ‘pivot’ was meant to underline this, but Asia has lost faith in the promise. There’s enduring uncertainty about President Trump’s Asia foreign policy, but even during the presidential primaries in 2016 both major parties were advertising a less proactive global policy, and thus a less plausible security guarantee for US allies in the region.

Many East Asian governments have already voted with their feet. President Duterte of the Philippines went to Beijing to tell his appreciative hosts that ‘Both in military—not maybe social—but economics also, America has lost.’45 Prime Minister Najib Razak of Malaysia, another longstanding US ally, followed shortly afterwards to discuss buying Chinese arms. President Joko Widodo of Indonesia has met with Xi at least five times since he came to power in 2014.

But beyond superpower rivalry, East Asia’s strategic environment will be shaped by economics. Most of the region’s growth over the past half-century has been derived from first-phase industrialisation, in which countries typically rely on their labour cost advantage to set up factories making high-volume, low-margin goods, many of them designed for export to the West. That model is running out of road. Wages are rising (China’s average wage tripled between 2005 and 201646), making Asian producers less competitive; Western markets are suffering, meaning that Western consumers are buying less; and better education and increased awareness, particularly about the environment, are making industrial expansion more challenging.

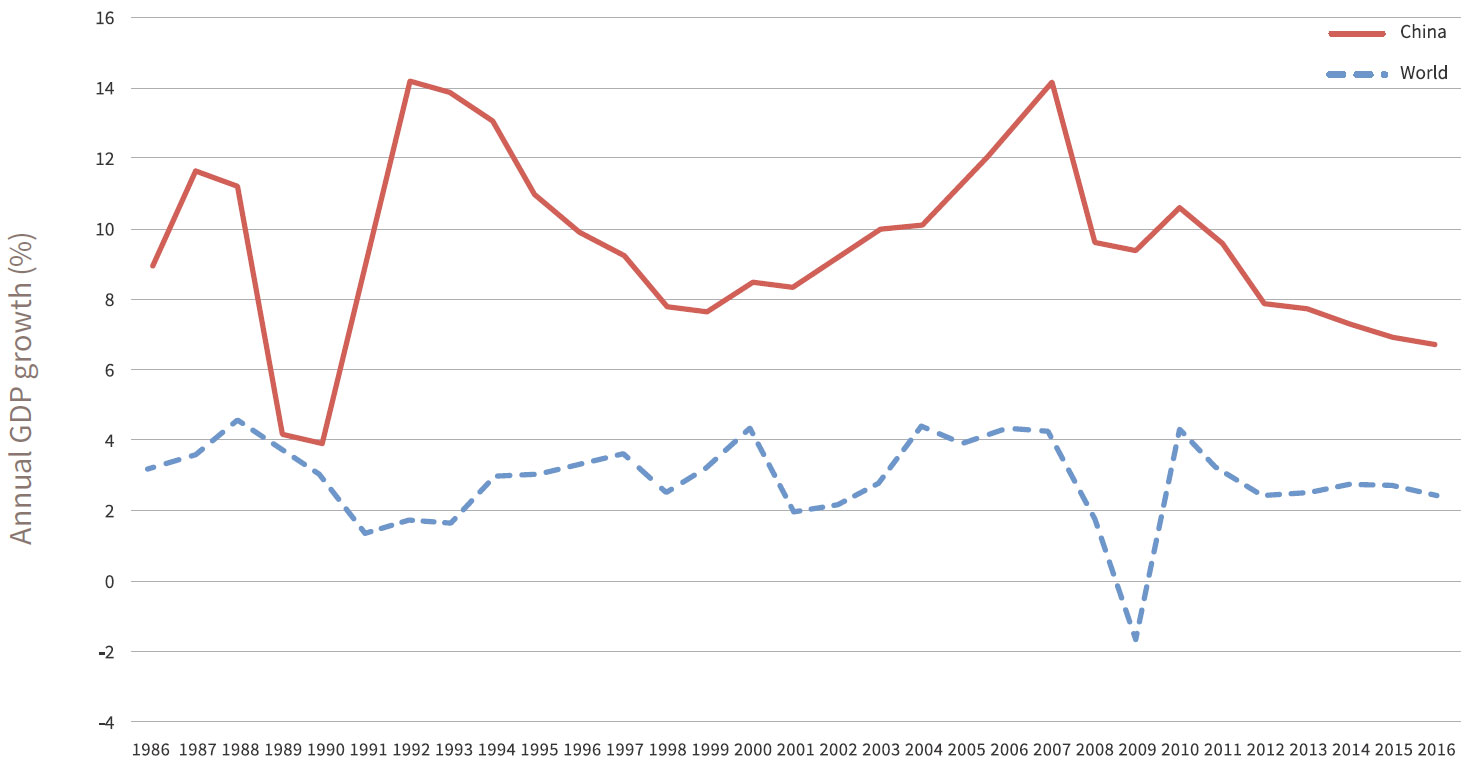

If East Asia is to maintain any kind of growth, it needs to move up the value chain, producing fewer goods at higher margins. This is expensive and difficult, involving investments in education, infrastructure and automation to improve productivity, and in the Asian context is politically risky, because it involves relinquishing government power over investment—and the opportunities for rent that it brings—to allow the markets to allocate capital more efficiently. Asia is failing these challenges. Productivity growth is slumping (Figure 2),47 and underdeveloped and over-restricted capital markets are limiting or misdirecting investment.

Figure 2: Annual economic growth, China and the world, 1986 to 2016

Asian economies are caught on the horns of a dilemma. If they fail to adapt to the changing economic realities, the hardship will provoke discontent among the workforce. But if they are to adapt to the new reality and avoid the middle-income trap, they’ll have to end the paternalistic, state-driven model and with it the supremacy of the elites who created the initial success and then rode it to its current demise, potentially provoking elite backlash. As the military coup in Thailand, or the resurgence of members of the old New Order elite such as Prabowo Subianto and Aburizal Bakrie in Indonesia, or the political turmoil in Malaysia show, the elites will resist change.

The uncertainties about the rise of China, the retreat of the US and the end of the old economic order are creating their own strategic dynamics. Governments across the region are still hoping for the best, but are preparing for the worst. Asia is rearming, with a focus on seaborne assets. It’s probably too early to describe this phenomenon as an ‘arms race’ because—with the exception of North Korea, which falls outside this analysis—it fails the test of truly competitive weapons development or purchases. But even if it’s not an arms race, the rearmament is problematic for two reasons. The first is that arms, particularly naval vessels, look like tools of aggression and so raise tensions even if they’re primarily designed for peaceful ends, such as the protection of fisheries; the second is that it re-empowers the generals—a class that has traditionally undermined democracy in Asia and in some cases continues to do so.

Case study: China

The need for integrated strategic and economic analysis is particularly acute in the case of China, not least because it has an extreme manifestation of the performance legitimacy difficulties faced by other countries in Asia.

China faces an array of social and environmental problems: corruption, growing inequality, pollution, unemployment, an ageing population, gender imbalance and restive minorities all make significant calls on the government’s attention. However, in the judgment of many analysts, most of those problems are either solvable or containable and, even together, don’t represent an existential threat to the continuing rule of the CCP.48

Similarly, most analysts looking at China’s economy in isolation see little risk of imminent collapse, despite an alarming slew of hindrances. The current challenges are on a superhuman scale: debt, particularly in the shadow economy; a potential banking crisis; an overdependence on real estate for savings; unproductive state-owned enterprises; rising wages; and the need to switch the main economic driver from investment to consumption. But again, economists say the government has the funds, and failing that the authority, to prevent an economic meltdown, even if it can’t prevent a hard landing.49

What these analyses often fail to take into account is how much economic weaknesses amplify social weaknesses and vice versa, potentially creating a destructive feedback loop between factors that are survivable on their own, but taken together have the potential to create an existential threat.

In the Western context, financial turmoil can undermine public faith in a particular government—as it did in 2008—but doesn’t generally call into doubt the system of government itself. The CCP still claims centrality in all aspects of China’s social and economic life.50 Any significant sign that it has lost control, even of relatively minor aspects, threatens to shatter the carefully maintained image that lies at the heart of the party’s mythology.

Beijing is aware of the danger. When the stock markets looked like they were starting to spin out of control in June 2015, the government stepped in with unprecedented measures, despite the fact that only 7% of China’s population owned stocks. As the Shanghai Composite Index fell, the authorities pledged an estimated $800 billion in market support,51 banned short selling and initial public offerings, persuaded large funds to buy stocks, prevented large shareholders from selling, and suspended 45% of the stock market from trading. On 24 August 2015, when the Shanghai Composite dropped 8.5%, prompting the state news agency Xinhua to dub it ‘Black Monday’, the Dow Jones Industrial Average opened down 1,089 points (6.6%, its largest one-day fall ever),52 but the US authorities allowed the markets to self-correct. In a normal economy, the Chinese reaction would be seen as an extraordinary over-reaction; however, such measures were probably necessary, given the devastating ramifications of a loss of public confidence in the government’s ability to manage the crisis.

The intervention shattered international markets’ confidence in the CCP’s promise to allow the markets a greater say in how the economy was run,53 but it achieved its principal aim of re-establishing the premise that the authorities were in control.

There are other, bigger, potential problems that would be considerably harder and more expensive to contain, not least because they involve significantly larger numbers of Chinese citizens. The real estate market is the cornerstone of savings for ordinary people: a collapse in prices triggered by an interest rate rise, or a loss of faith in resaleability, would have social repercussions that would outweigh mere economics.

Similarly, a public loss of confidence in so-called ‘wealth management products’ (WMPs) would be similarly devastating. WMPs are lightly regulated fixed-term investment funds that offer high rates of return but which, as an asset class, are notoriously opaque about how they use the invested money. In March 2017, outstanding WMPs were worth some $4.2 trillion, or 39% of GDP, up 19% year on year.54 Many ordinary investors believe that WMPs have an implicit government guarantee.55 Chinese authorities have tried to disabuse investors of this notion, but the CCP has never allowed a WMP to formally default. Analysts believe that a substantial number of new WMPs are being issued to repay old WMPs that have failed to meet their investment targets—the classic definition of a Ponzi scheme.56 A catastrophic unwinding of the WMP market would not only present a bill that would strain even China’s public finances beyond breaking point, but also severely damage the credibility of the government as a competent manager.

As a number of commentators have pointed out, Chinese Government intervention in the stock market and to prop up the WMP market has introduced a worrying level of moral hazard into the economy.

Although China is an extreme case of the connectivity between economic and strategic risk, the risks that it embodies are to a greater or lesser extent felt by many, if not most, of the other governments in East Asia.

Conclusion

The strategic challenges facing East Asia are being amplified by economic uncertainty and by the narrow reliance of governments on their ability to deliver growth for political legitimacy. For years, politicians the world over, but especially in East Asia, have won support by writing cheques that they could honour only if the relentless cycle of supercharged economic growth continued unabated. Now that cycle looks to be coming to an end, the default fallback position seems to be demagoguery. Asia is particularly vulnerable to economic shocks, and the slowing global economy risks fragmenting both social consensus within nations and cooperation between them.

Recommendations

Partner nations should:

- improve the integration of economic and political analysis to better predict upcoming crises (many of the standard analytical models of strategic risk pay too little attention to the impact of economic slowdown)

- encourage governments in East Asia to widen their basis for legitimacy (reliance on delivering growth for legitimacy becomes a significant risk when the global economy is slowing; diversity helps maintain stability)

- encourage the growth of social institutions that can provide legitimate outlets for discontent (repression is a short-term solution; if the underlying problems aren’t solved, anger builds until it explodes)

- ensure that justice systems deliver fair redress (if the courts are seen to be exacerbating economic and social inequality as prosperity recedes, that will amplify discontent)

- improve opportunities for disadvantaged communities (the risk of violence grows as the opportunity cost of challenging the status quo decreases; disadvantaged communities need to believe that they have a stake in stability)

- accelerate peace negotiations with militant groups in Myanmar, the southern Philippines and Southern Thailand to head off cross-fertilisation with transnational jihadi groups (which have proved adept at incorporating local grievances, including anger over economic exclusion, into their narratives of violence).

Notes

1 Edward Miguel, Shanker Satyanath, Ernest Sergenti, ‘Economic shocks and civil conflict: an instrumental variables approach’, Journal of Political Economy, 2004, 112(4):725–753.

2 Ted Robert Gurr, Why men rebel, Princeton University Press, 1970.

3 Samuel Huntington, Political order in changing societies, Yale University Press, 1968.

4 Full text of Constitution of Communist Party of China (as adopted at 18th CCP National Congress, 2012), Xinhua, 19 March 2013.

5 Agence France-Presse, ‘Philippines’ elite swallow country’s new wealth’, Philippine Inquirer, 3 March 2013.

6 World Bank, East Asia Pacific economic update, October 2016.

7 Data: World Bank.

8 Francesco Abbate, Silvia Rosina, ‘ASEAN–China trade growth: facts, factors and prospects, New Mandala, 14 June 2016.

9 Allan Dizioli, Jaime Guajardo, Vladimir Klyuev, Rui Mano, Mehdi Raissi, Spillovers from China’s growth slowdown and rebalancing to the ASEAN-5 economies, IMF working paper WP/16/170, IMF, Washington DC, 2016.

10 Jon Emont, ‘Foreigners have long mined Indonesia, but now there’s an outcry’, New York Times, 31 March 2016.

11 This is an underestimate. Intra-Asian trade accounted for 52% of Asian trade, but much of this was in part-manufactures that were eventually exported to markets in Europe and the US. World Trade Organization, International trade statistics 2015, WTO, Geneva, p. 41.

12 Sonali Jain-Chandra, Tidiane Kinda, Kalpana Kochhar, Shi Piao, Johanna Schauer, Sharing the growth dividend: analysis of inequality in Asia, IMF working paper WP/16/4, IMF, Washington DC.

13 Graeme Blair, C Christine Fair, Neil Malhotra, Jacob N Shapiro, ‘Poverty and support for militant politics: evidence from Pakistan’, American Journal of Political Science, 2012, 57(1):30–48.

14 World Bank, World development report 2011, World Bank, Washington DC, p. xi.

15 See Alan B Krueger, Jitka Maleckova, ‘Education, poverty and terrorism: is there a connection?’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2003, 17(4).

16 James D Fearon, Governance and civil war onset: background paper, World Bank, Washington DC, 2010, p. 25.

17 John McBeth, ‘Jokowi’s Golkar gambit’, The Strategist, 8 June 2016.

18 Malcolm Cook, Lorraine Salazar, The differences Duterte relied upon to win, Institute of South East Asian Studies, 22 June 2016.

19 Apart from the recent headline problems with the Trans-Pacific Partnership, ASEAN’s attempts to expand the breadth of the ASEAN Economic Community have also stalled.

20 See Andrew Berg, Jonathan Ostry, Inequality and unsustainable growth: two sides of the same coin?, IMF staff discussion note SDN11/08, IMF, Washington DC, 8 April 2011.

21 See Nouriel Roubini, ‘Economic insecurity and the rise of nationalism’, The Guardian, 2 June 2014.

22 ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community scorecard 2012.

23 David Gold, ‘Economics of terrorism’, no date.

24 World Trade Organization (WTO) data, WTO, Geneva.

25 Asian Development Bank data, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

26 Neal E Boudette, Jeff Bennett, ‘Pigment shortage hits auto makers’, Wall Street Journal, 26 March 2011.

27 See Charles Clover, Long Jung-a, ‘China turns screw on corporate South Korea over US missile shield’, Financial Times, 5 January 2017.

28 ASEAN, ASEAN statistical yearbook 2014, ASEAN, Manila, p. 125.

29 Robert B Zoellick, Fragile states: securing development, World Bank, Washington DC, 12 September 2008.

30 Eric Sasson, ‘Blame Trump’s victory on college-educated whites, not the working class’, New Republic, 15 November 2016.

31 Lord Ashcroft, ‘How the United Kingdom voted on Thursday… and why’, Lord Ashcroft Polls, 24 June 2016.

32 RG Cruz, ‘Why Duterte is popular among wealthy, middle class voters’, ABN–CBS News, 1 May 2016.

33 See Michael Peel, ‘Thailand offers $1 billion loan to rice farmers in push to boost prices’, Financial Times, 1 November 2016.

34 China–Philippines, China–Malaysia, China–Vietnam, Vietnam–Cambodia, Cambodia–Thailand, Philippines–Malaysia, Malaysia–Indonesia etc.

35 Blair et al., Poverty and support for militant politics.

36 See Krueger & Maleckova, ‘Education, poverty and terrorism: is there a connection?’.

37 Gold, ‘Economics of terrorism’.

38 International Crisis Group, Exploiting disorder: al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, 14 March 2016.

39 There are other areas of concern, including Buddhist violence in Myanmar, communist violence in the central Philippines, and the fact that jihadist groups seem to be using Malaysia as a transit point for men and money.

40 Olivier Roy, ‘Who are the new jihadis?’, The Guardian, 13 April 2017 (extracted from Jihad and death: the global appeal of Islamic State).

41 Both Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders Front) and Hizb ut-Tahrir (Party of Liberation) were heavily involved in the political opposition to Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, better known as Ahok, a Chinese-Indonesian Christian who was governor of Jakarta.

42 Gold, ‘Economics of terrorism’.

43 Speech by Xi Jinping on China–US relations, Seattle, 24 September 2015, China.org.cn.

44 ‘China’s policies on Asia–Pacific security cooperation’, Xinhua, 11 January 2017.

45 Ben Blanchard, ‘Duterte aligns Philippines with China, says America has lost’, Reuters, 20 October 2016.

46 See Douglas Bulloch, ‘China is running out of cheap rural labor and it’s because of failed reforms’, Forbes Magazine, 3 March 2017.

47 See Nicholas Sutcliffe, Siddharth Mehta, ‘Challenges from slowing productivity growth in Asia’, Brink Asia, 6 March 2016.

48 See, for example, Ho-Fung Hung, Arthur Kroeber, Howard W French, Suisheng Zhao, ‘When will China’s government collapse?’, Foreign Policy, 13 March 2015.

49 See, for example, Jonathan Woetzel, ‘5 reasons why China’s economy won’t collapse’, McKinsey China, 14 October 2015..

50 ‘The Communist Party of China is the vanguard both of the Chinese working class and of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation. It is the core of leadership for the cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics and represents the development trend of China’s advanced productive forces, the orientation of China’s advanced culture and the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people.’ From the preamble of the Constitution of Communist Party of China.

51 Scott Cendrowski, ‘China’s “Black Monday” as stock market dives 8.5%’, Fortune International, 24 August 2015.

52 Matt Egan, ‘After historic 1,000-point plunge, Dow dives 588 points at close’, CNN Money, 25 August 2015..

53 ‘China vows bigger role for markets as party closes summit’, Bloomberg News, 12 November 2013.

54 ‘China cools growth in wealth products worth trillions of dollars’, Bloomberg News, 24 April 2017.

55 ‘China is playing a $9 trillion game of chicken with savers’, Bloomberg News, 11 April 2017.

56 See ‘Bank of China executive warns of shadow banking risk’, Reuters, 12 October 2012.

About the Author

Tim Johnston is an independent strategic risk consultant. Until recently, he was the Asia Program Director for the International Crisis Group, a non-profit research and analysis organisation focused on conflict prevention and mitigation. For 20 years, Tim was an Asia-based journalist, living in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Singapore, East Timor, Indonesia, Thailand and Hong Kong. After leaving journalism, he worked for HSBC as Head of News in the Asia–Pacific, helping craft the bank’s public response to the ebbs and flows of economic trends in Asia.

The thumbnail external pageimagecall_made is courtesy of giorgio raffaelli/Flickr. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.