Peace Operations and Prevention for Sustaining Peace: The Restoration and Extension of State Authority

24 Mar 2017

By Youssef Mahmoud and Delphine Mechoulan for International Peace Institute (IPI)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageInternational Peace Institute (IPI)call_made on 16 March 2017.

As member states continue to discuss what sustaining peace means in practice,1 it is important to examine how peace operations can be designed and implemented to help build self-sustaining peace rather than just prevent relapse into conflict. This issue brief will focus on how “the restoration and extension of state authority,” a recurrent mandate of several peacekeeping operations, can be tailored to achieve this objective. It is suggested that the primacy of politics, people-centered approaches, context-sensitive analysis, performance legitimacy, and rule of law, rather than simply stabilization, must drive this process.

The responsibility of a state, as defined in contemporary political theory, is to deliver a range of public goods and services to its citizens and create inclusive structures and processes that enable them to participate in public policy debates and fulfill their legitimate needs and aspirations without fear, with justice, and in security. Only then can the state secure compliance with legitimate political, legislative, administrative, and legal decisions enacted on citizens’ behalf. It is this quid pro quo that creates a trusting relationship between the governors and the governed.

When countries are under stress or in conflict, states tend to focus on how power is acquired, maintained, and exercised rather than on people-centered governance. In situations where the state has residual capacities to provide some basic services, the lion’s share of these capacities tends to be directed toward security and is sometimes skewed toward state security or regime security rather than human security.

In situations where there is or has been conflict that has adversely affected the state, the restoration or extension of state authority is judged necessary for securing sustainable peace.2 The majority of current peace operations are deployed in countries with weak state institutions, limited or absent administrative, judicial, and security capabilities, and in some instances, a pervading mistrust between the central government and outlying territories.

Therefore, one of the questions that needs to be asked is: Which authority or authorities are these peace operations expected to reestablish and for what purpose? Moreover, is it government or governance that is being decentralized— in other words, is decentralization a process where the center is extending its control over the periphery or empowering existing, resilient governance capabilities in the periphery? What activities can peace operations engage in to support the return and extension of state authority? And how might these activities look from the perspective of prevention and sustaining peace? This paper aims to offer some reflections on the above questions.

Extension and Restoration of State Authority in Peace Operations

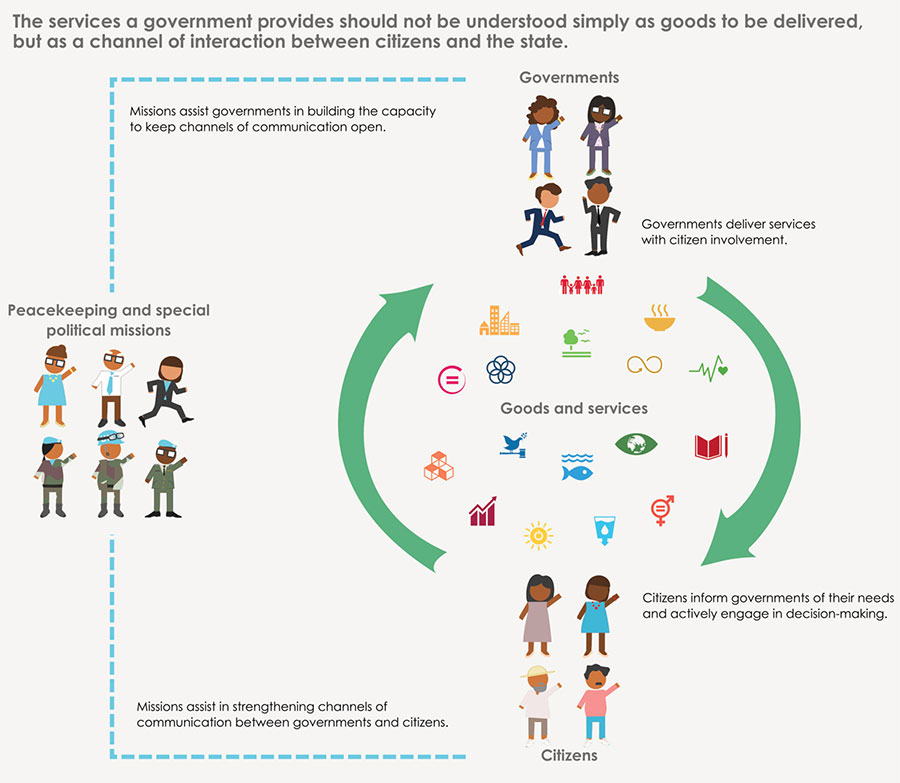

Although no fixed definition has been established, the extension of state authority is generally understood “as a set of activities that are conducive to strengthening the authority of the government over a country’s territory in a legitimate manner.”3 The services the state is expected to provide “should be understood not simply as a good to be delivered but as a channel of interaction between citizens and the state.… This, in turn, supports the view that state legitimacy is an ongoing process that governments must continually engage in, rather than an outcome they can achieve and be done with.4

Box 1. Extension of state authority in the DRC, Liberia, and Somalia

UN Security Council Resolution 2277 (2016) renewing the mandate of the UN mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) emphasized that the mission’s support for the restoration of state authority should be carried out under the international stabilization plan. This plan aims in part at opening up government access to certain regions and increasing the provision of services in an effort to increase the government’s credibility.

In Security Council Resolution 1509 (2003) on Liberia, state authority is associated with the proper administration of natural resources, SSR, electoral support, and security. Interestingly, the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) experimented with regional hubs aimed at improving citizens’ access to governance structures and services.6 While some level of service delivery was realized, it did not necessarily improve accountability.

In Somalia, the integrated office of the resident coordinator/deputy special representative of the secretarygeneral (RC/DSRSG) developed a Community Recovery and Extension of State Authority/Accountability (CRESTA/A) approach/unit in 2016, which aims to link top-down statebuilding with bottom-up, community-led recovery. It does so by enabling the government to engage with local communities in “newly recovered areas and support the outreach and dialogue process that will bring the community together and establish a system allowing disputes to be resolved through a recognized mechanism…and resources to be shared equitably.”7

In peace operations, activities associated with assistance to the return or reestablishment of state authority range from support for political participation, state capacity building, and the return of rule of law institutions, to security sector reform (SSR) and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) (see Box 1).

The initial focus for both the host government and the UN tends to be on reestablishing the state’s territorial control. In dire security situations, the return of relative safety is understood as the necessary first step. This is often done via the deployment of military peacekeepers and state security forces to enable the return or (re)deployment of civilian staff and state representatives. While the physical presence of the state is undeniably important in bolstering its image, this does not automatically improve perceptions of state authority and does even less for its perceived legitimacy. Indeed, in the eyes of the public, what is restored may be a state and institutions whose legitimacy is contested, or whose previous policies were drivers of conflict (see Box 2)

Box 2. Extension of state authority in Mali

Security Council Resolution 2295 (2016) extended the mandate of the UN mission in Mali (MINUSMA) to support the reestablishment of state authority throughout the country. But eighteen months after the signing of the June 2015 peace agreement, tangible outcomes are still largely missing. The mission’s understanding of the return of state authority as outlined in the secretary-general’s report from May 2016 appears to focus first on the return of state administration and defense and security forces, and second on facilitating the delivery of basic services. The mission’s activities supporting the return of state authority fall under most of its pillars of work aimed at facilitating the implementation of the peace agreement.

Many of MINUSMA’s activities are designed to support traditional initiatives to manage conflict and build local capacity, reflecting an understanding that the return of state authority should empower local and traditional authorities. However, in places such as Kidal where security is dire, the mission is often compelled to assist the state in its securitization strategy.

Another problem exists in Timbuktu, where residents have deemed government officials from the south as non-representative (and these officials themselves perceive being posted in the north as a punitive measure). In instances where very few local, northern representatives have been appointed, the necessary backing from the central government to work toward reestablishing a legitimate state is lacking.

As outlined in this paper, establishing a legitimate and functioning state as the principal safeguard against relapse into conflict is crucial. It is, however, an endeavor that requires several decades and hence outlives the lifetime of a peacekeeping operation. Trying to achieve quick fixes and rapid results, though important and sometimes unavoidable (for example in crisis and live-conflict situations), may not be the most effective and durable way of promoting the reestablishment and restoration of legitimate state authority.

The process, in fact, is as important as the goal, and the principles of inclusive local ownership should be highlighted. Moreover, it is important to emphasize the mission’s enabling role rather than its potential to substitute itself for the state (see Box 3). The Advisory Group of Experts entrusted with the ten-year review of the UN peacebuilding architecture argued that UN missions need to empower and engage with traditional authorities, civil society actors, the private sector, and religious and academic leaders as they would with the host country’s central government.

Box 3. Extension of state authority in the Central African Republic

Security Council Resolution 2301 (2016) indicates that the UN mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) should support “the reconciliation and stabilization political processes, the extension of State authority and the preservation of territorial integrity.” As in other missions, the civil affairs section and the political affairs division, together with the human rights division, conduct many of the initiatives aimed at extending state authority. However, due to an extremely limited government presence, the mission ends up “playing a leading role in delivering services or taking decisions which are expected from state institutions.”8 In instances where the state is absent, the line between enabling state authority and replacing it is extremely fine and becomes difficult to manage.

Figure 1. A sustainable model for the extension and restoration of state authority

Extending State Authority from a Sustaining Peace Perspective

What would a mandate to support the extension or return of state authority look like if it were designed and implemented with the intent of preventing the return of conflict and of sustaining peace after the mission has left? This paper provides a few concrete suggestions.

Context-sensitive and inclusive analysis: Context-sensitive analysis is critical. The analysis should include not only the factors that impede peace, but also the capacities that still function and could serve as a foundation for extending state authority. The analysis should be conducted in a participatory manner that takes into account national and local perspectives, particularly of women and youth.

Mission-wide strategy for sustaining peace: An important step for peace operations is to develop, on the basis of the above analysis, a mission-wide strategy for sustaining peace (i.e., the primacy of politics). Supporting the extension of legitimate state authority would be but one of many strands in such a strategy. For country situations on its agenda, the Peacebuilding Commission, in its revitalized role, could lend valuable support to this exercise, drawing on the extensive knowledge of country-specific configurations and its Working Group on Lessons Learned.

People-centered approaches: The extension of state authority cannot focus solely on the (re)deployment to the periphery of central state institutions, but must ensure that state institutions and mechanisms supported by peace operations are participatory. This implies a need for a bottomup, people-centered approach where local communities play an important role in decision making and where progress is not only measured in terms of the redeployment of state institutions, but also in terms of how people’s daily lives are positively affected. To the extent possible, peace operations should facilitate such an approach, which would involve them enabling more and doing less.

A compact of mutual accountability: The special representative of the secretary-general (SRSG) and mission leadership, acting on behalf of the Security Council, should engage in conversations with the host government in the initial stages of a mission’s deployment to develop a shared understanding of what is meant by “extension of state authority” and how it should be carried out in ways that enhance its legitimacy and lay the foundations for sustaining peace. The outcome of such a conversation would be an agreement on governance benchmarks to be achieved by the host government and matched by support activities from the UN mission. Such an agreement of mutual accountability would also inform the mission’s exit strategy. Under such a scheme, the host government would be expected, through an appropriate modality, to provide periodic progress reports to the Security Council, as would the UN mission through the standard reporting mechanisms.

Conclusion

Overall, the restoration and extension of state authority provides an opportunity to embed the mandates of peacekeeping operations and special political missions in the concept of sustaining peace. Ideally, such mandates should not be excessively detailed, allowing missions to establish needs and tasks through on-the-ground consultations. By approaching the implementation of their mandates from a sustaining peace perspective, peace operations would play a more enabling and less intrusive role.

Notes

1 Peter Coleman, “The Missing Piece in Sustainable Peace,” Earth Institute, November 6, 2012, available at http://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2012/11/06/the-missing-piece-in-sustainable-peace.

2 UN Security Resolution 2282 (April 27 2016), UN Doc. S/RES/2282 (2016).

3 Jake Sherman, “Peacekeeping and Support for State Sovereignty,” in Annual Review of Global Peace Operations, Center on International Cooperation (New York: Lynne Rienner, 2012).

4 Jue Gao, et al., “Extending Legitimate State Authority in Post-Conflict Countries: A Multi-case Analysis” (capstone project, School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, May 2015), available at https://sipa.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/UNPBSO%20Capstone%20-

%20ELSA%20Final%20Report_FOR%20PUBLICATION.pdf.

5 Rachel Gordon and Dyan Mazurana, “Can Services Deliver Legitimacy and Build Peace?” UN University, May 7, 2015, available at http://cpr.unu.edu/can-services-deliver-legitimacy-and-build-peace.html .

6 Marina Caparini, “Extending State Authority in Liberia: The Gbarnga Justice and Security Hub,” NUPI, 2014, available at http://hdl.handle.net/11250/226333.

7 United Nations, “Programme Quarterly Progress Report (January–June 2016): Support to the Federal Government of Somalia in Stabilization in Newly Recovered Areas,” available at www.so.undp.org/content/dam/somalia/Reports/Q2-2016/UN%20MPTF%20Biannual%

20Progress%20Report%20Support%20to%20Stabilization%20Project-final.pdf.

8 UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support, Civil Affairs Handbook, 2012, p. 198.

About the Authors

Youssef Mahmoud is a Senior Adviser at the International Peace Institute (IPI).

Delphine Mechoulan is a Policy Analyst at IPI.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.