Russian Analytical Digest No 189: State Duma Elections

14 Oct 2016

By Ora John Reuter and Andrey Shenin Saratov for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The two articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 29 September 2016.

Analysis

2016 State Duma Elections: United Russia after 15 Years

By Ora John Reuter

Abstract

For 15 years, United Russia has been the primary electoral vehicle of the Kremlin, and it won a landslide victory in the 2016 State Duma elections. United Russia’s dominant performance is attributable to five main factors: Putin’s popularity, elite cohesion, institutional design, the use of administrative resources, and an effective electoral strategy. From afar, United Russia’s dominance made these elections seem uneventful, but beneath the surface, the election exposed several problems that the regime will have to confront in the future. In particular, the party is still faced with the perennial challenge of ensuring elite cohesion and, as the economic crisis continues, United Russia will find it increasingly difficult to maintain social support. In this article, I analyze three elements of United Russia’s dominance: its relationship to Putin, its position among political elites, and its electoral strategy.

United Russia and Vladimir Putin

United Russia has been closely linked to Vladimir Putin since its founding. In contrast to his predecessor Boris Yeltsin, Putin has actively promoted the creation and maintenance of a dominant party in Russia. In turn, the party owes much of its success to Putin. Many vote for the party because they view it as “Putin’s Party.” Seventy-nine percent of respondents in the 2012 Russian Election Study said that Putin’s chairmanship of United Russia was “important to them” when deciding whether to vote for the party. UR leaders never miss an opportunity to remind voters that Putin helped found the party and that he is the “moral leader” of the party. Putin’s patronage is also important for attracting commitments from the political elite. After all, if they are to tie their fates to a centralized party like United Russia, elites must know that the Kremlin stands behind that party and that spoils will be channeled through it.

Putin clearly recognizes that his affiliation with the party brings such benefits. At the same time, there are costs. Primary among them is the possibility that Putin’s own rating might be tarnished if United Russia’s rating begins to fall. Indeed, after becoming party chairman in 2008 and frequently participating in party functions during his four years as prime minister, Putin began to distance himself from the party in 2012 when United Russia’s ratings declined. In 2012 and 2013 he met with party leaders only rarely and conspicuously opted not to speak at the party’s 14th Congress.

Like so much else in Russian politics, the crisis in Ukraine changed things. Amidst a patriotic fervor, United Russia’s ratings reached historic highs in 2014–15. Being closely associated with United Russia was no longer dangerous for Putin, so he once again began attending party events and meeting publicly with party leaders.

In the lead-up to the 2016 elections, Putin continued this practice. He attended candidate forums, met with party leaders, and spoke warmly of the party during his annual call-in show. Such signals reassured the elite that UR would continue to be the Kremlin’s primary electoral vehicle. At the same time, the Kremlin still wanted to hedge its bets during the campaign and the decision was made to keep some distance between Putin and UR. For example, while UR candidates spoke frequently of the party’s relationship with the president, the party was not allowed to use Putin’s image in its campaign materials.

United Russia and the Political Elite

Recent history shows that electoral authoritarian regimes are often brought down by elite defections. As a dominant party, one of United Russia’s main functions is to prevent such schisms. Elite cohesion is maintained via a combination of institutional carrots and sticks. In terms of sticks, the party leadership monitors the behavior of cadres and sanctions disloyalty. In return for their loyalty, party cadres receive career benefits. In regimes with dominant parties, the distribution of spoils is determined, at least in part, by regularized norms and procedures embedded within the party. If party cadres remain loyal and serve the party, they have good reason to believe that they will continue to share in the benefits of office. United Russia tries to achieve this by ensuring cadre rotation at higher levels and rewarding long-serving party members with promotion. In the State Duma for example, the party’s faction typically experiences significant turnover in each new convocation (in 2011 almost half of the legislative faction turned over and in 2016 one third of the faction turned over). Vacant spots are filled by up-and-coming party members from the regions. Similarly, Reuter and Turovsky found that length of service in the party was a strong predictor of promotion in regional legislatures in the 2000s.1

Due in large part to United Russia, the regime has managed to avoid significant elite splits over the past 15 years. One technique that political scientists have used to measure regime cohesion is to look at how many opposition candidates are defectors from the ruling party. As Tables 1 and 2 show the number of defections in Russian elections has been low in recent regional elections. And while full data has yet to be gathered, the 2016 election cycle appears to be no exception.

At the same time, several recent developments will make it more difficult for United Russia to maintain elite cohesion in the near future. The reintroduction of single member districts (SMDs) will weaken the central party leader’s control over faction members. In order to secure reelection, party list deputies must curry favor with the party leadership, which composes the party list. By contrast, single member district deputies owe their seats to voters (and the powerful regional elites, who help them get elected).

For Russia’s leaders, unruliness among SMD deputies is not just an abstract problem. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Kremlin struggled to build coalitions among fractious SMD deputies. After the 2003 elections, United Russia eliminated the SMD component in Duma elections in order to establish tighter control over deputies. United Russia might have won even more seats if it had retained the SMD component, but, from the Kremlin’s point of view, it was more important to reign in powerful regional elites. For the 2016 elections, however, the SMD component was reintroduced. With United Russia’s ratings faltering in 2013, the Kremlin believed that it would need to take advantage of disproportional electoral rules—first-past-the-post elections inherently favor large parties—in order to retain its majority in the next Duma. The Kremlin calculated that it had established sufficient control over regional elites to risk this institutional change. But this control is precarious. If the economic crisis continues and United Russia’s popularity falters, SMD deputies will likely be the first to distance themselves from the regime. This could be especially perilous for the Kremlin given that 59% of UR faction members will be SMD deputies. For the Kremlin, the reintroduction of the SMD component is risky also because it strengthens regional governors, who have been directly elected since 2012. In the 1990s, regional governors expanded their political power by packing the Duma with their clients, mostly via SMD races. The 2016 elections saw a resurgence of this practice. As Slider and Petrov point out the vast majority of UR SMD deputies in the new Duma have strong connections to the region and many of these deputies are clients of regional governors.2

Governors have been further strengthened by institutional changes at the regional level. In 2013, federal law was amended to allow regional legislatures to decrease— from 50% to 25%—the share of their deputies elected on party lists and completely eliminated the requirement for party list components in local elections. While most regions have retained a 50–50 balance between party list and SMD components, many major cities have now switched to SMD elections.3 These reforms give governors the opportunity to pack regional and local legislatures with more of their clients, a practice that often leads them into conflict with the central party leadership. For example in 2015, Samara governor Nikolai Merkushkin was publicly threatened with expulsion from the party after he backed a number of independent candidates that had not participated in local UR primaries.4 Merkushkin was forced to back down in the end, but the episode underlines the dangers posed by giving governors additional institutional incentives to expand their political machines. Indeed, in the 2015 regional elections governors in almost all regions headed the list of United Russia, even though the Kremlin had publicly told governors not to do so.5

Although governors have been directly elected since 2012, the Kremlin has kept tight control over these elections and Putin retains the right to remove sitting governors from office. This, quite obviously, limits the autonomy of regional governors. But nonetheless, the independent electoral mandate that governors now have is an autonomous resource that they lacked for much of the 2000s. If the economic crisis continues and/or United Russia’s rating falls, it is not inconceivable that one or more governors might use their electoral legitimacy to challenge the Kremlin.

Another institutional innovation that could affect United Russia’s ability to maintain elite cohesion is the decision to hold primaries. Several motivations have been offered for United Russia’s decision to introduce primaries. Some have argued that it is an attempt to identify strong candidates and weed out bad ones. Others have said that it is an attempt to legitimize otherwise arbitrary cadre decisions. Still others argue that it is a mobilizational device, aimed at generating enthusiasm among the party’s base. Whatever the reason, it is clear that that intraparty competition breeds conflict among party members. Indeed, in a number of regions—such as Chelyabinsk, Yaroslavl, and Khabarovsk—the losers of UR primaries defected from the party and ran as independents or for opposition parties.6 Of course, United Russia could always decide to do away with primaries if they create too much intra-party strife. But to the extent that UR’s leaders calculate that the primaries are necessary, they will have to pay the cost of elite discord.

United Russia at the Polls

United Russia won its largest ever majority in the 2016 elections. Fraud and manipulation, while much less widespread than in 2011, still undoubtedly played a role.7 In the run-up to the elections, the Kremlin repeatedly emphasized the need for transparency and legitimacy. Respected human rights advocate, Ella Pamfilova, was named to head the Central Election Commission, replacing Vladimir Churov, who had presided over widespread fraud during the 2011 elections. By all indications, the Kremlin seemed sincere in its desire for cleaner elections, yet several features of the system made fraud all but inevitable. Since at least 2005, local officials and governors have been evaluated on their ability to mobilize votes for United Russia.8 Believing that reappointment depended on the relative performance of UR in their jurisdictions, local officials have ample incentive to pad UR’s vote totals. In addition, the above-mentioned institutional changes gave regional elites even more reason to ensure that their clients were elected.9 Thus, even if the Kremlin did not want fraud to be employed, it most likely was.10

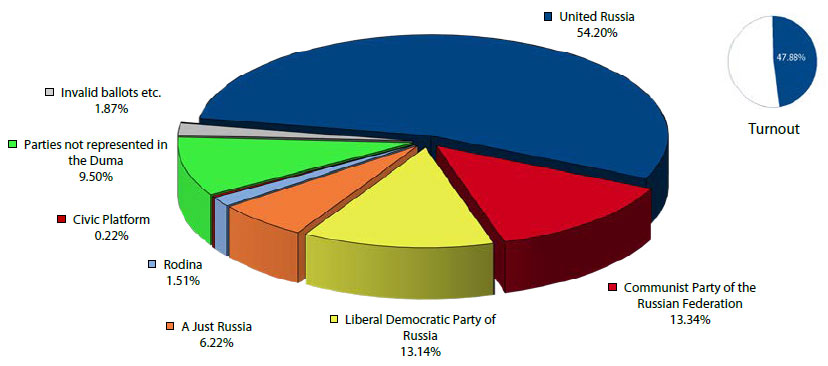

The electoral system also played a major role in helping UR secure a constitutional majority. United Russia won 54% of the vote on the party list component, but it won 62% of party list seats and 90% of SMD seats. The single member district results were strongly disproportional by their very nature. In addition, districts were heavily gerrymandered in order to dilute the vote in large cities, which have increasingly voted against UR in recent years. In the party list component, meanwhile, United Russia’s seat total was helped by the fact that, as the largest party, it was entitled to a majority of the “wasted votes” garnered by parties that failed to clear the 5% threshold. Many electoral authoritarian regimes use mixed systems, and these elections show why. Disproportionality in the SMD component favored the largest party, while the existence of party list component gave opposition parties a disincentive to coalesce.

Another determinant of United Russia’s vote total was the political machines of Russia’s regional elites. In 2003 and 2007, United Russia relied heavily on regional governors to help it mobilize votes. With the switch to gubernatorial appointments, however, many powerful governors were replaced by colorless bureaucrats who struggled to win votes for the Kremlin. In 2011, therefore, the role of governor machines was diminished. In 2016, the importance of gubernatorial machines declined still further, but they were by no means insignificant. In the end, 19 of UR’s 35 regional lists were headed by regional governors, and initial analyses indicate that UR did much better in regions with popular governors.

Thus, a significant part of United Russia’s seat share is directly due to the use of administrative resources, a disproportional electoral system, and the political machines of regional elites. However, a large part of United Russia’s vote share was and always has been determined by the preferences of voters (mediated as they may be by the mass media and the available menu of options). As noted above, much of the party’s electorate votes for it because it is seen as Putin’s party. Still, the party’s platform was not entirely devoid of programmatic content. On foreign policy issues, the party’s campaign message was less antagonistic toward the West than the KPRF or LDPR, but the campaign still contained undertones of anti-Westernism. On economic issues, meanwhile, United Russia maintained its traditional center-right stance. Socially, the party has become increasingly conservative over the past several years and this trend continued into this campaign.

However, the 2016 campaign was more noteworthy for its lack of ideological content. As is common for authoritarian dominant parties, United Russia tried to paint its dominance as an inherently attractive quality. Agitator training materials instructed activists to convey the idea that, “United Russia is the party of a majority of Russians, and the majority can’t be mistaken.”11 Campaign materials emphasized that United Russia was a known quantity, while the opposition was unknown and irresponsible. Voters were asked to consider not whether United Russia was a good choice, but whether it was better than the alternatives.12

On the whole, however, the campaign was quiet, with much less partisan agitation than in 2007 or 2011. With the reintroduction of the single member district races, local issues featured much more prominently in the campaign. This suited United Russia, allowing it to highlight its various clientelist projects, especially outside large cities.

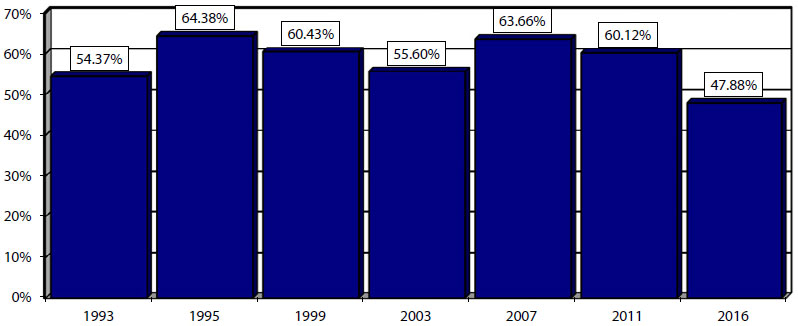

The low intensity of the campaign contributed to historically low turnout. At 48%, turnout in these elections was lower than in any other State Duma election. Turn-out was also affected by timing—the election was held at the end of the summer vacation season—and by the perception that a United Russia victory was inevitable. Turnout is a double-edged sword for the Kremlin. One the one hand, high turnout contributes to regime legitimacy and allows the regime to gather quality information about local grievances. On the other, politicizing the electorate in order to ensure high turnout also poses risks, because politicized voters are more likely to challenge the regime. This suggests that autocrats have an incentive to sow apathy, at least among some segments of the population.

Voter turnout and UR vote share are typically correlated, but much of this correlation is likely due to ballot box fraud (ballot-box stuffing leads to a mechanical correlation between the two) and administrative resources. The pattern in recent regional elections has been for United Russia to depoliticize well-educated, urban voters and rely more on turnout among dependent voters (e.g. rural voters, pensioners, state employees) who respond well to state mobilization and clientelist appeals. This pattern was also evident in the 2016 elections.

Looking Ahead

United Russia’s electoral future is less clear than its land-slide victory would suggest. Much of the party’s success in 2016 was due to disproportional electoral rules, but the same institutional changes that favored United Russia in this election will make elite schisms more likely in the long run. United Russia also benefited significantly in these elections from the patriotic sentiment that has persisted in Russia since the annexation of Crimea. But this patriotism appears to be fading, if slowly. In future elections, UR may seek to rely even more on patronage spending directed at dependent sectors, but such tactics strain the budget, and if oil prices remain low, this type of spending will be unsustainable. Of course, United Russia could always lean more heavily on coercive mobilization and fraud, but such tactics further delegitimize the regime and, as 2011 showed, can lead to mass unrest. In sum, United Russia may face significant challenges in the near future.

Table 1: Defections from United Russia in Gubernatorial Races, 2012–2015

Source: Author’s database.

Table 2: UR Defectors Among Top Opposition Candidates in Regional Legislative Elections, 2009–2014

Source: Author’s database.

Notes

1 Ora John Reuter and Rostislav Turovsky. 2014. “Dominant Party Rule and Legislative Leadership in Authoritarian Regimes” Party Politics. 20(5)

2 Darrell Slider and Nikolai Petrov. 2016. “’Just Good Enough’ Elections While Maintaining Control,” Russian Analytical Digest.

3 See “Inertsiya Vertikali: Kreml’ teryaet kontrol’ nad regional’nymi elitami” Slon.ru 27 January 2016

4 “Samarskomu gubernatoru nameknuli o partiinoi otvetsvennosti” Kommersant. 13 August 2015. See also “Nikolai Merkush- kin protivopostavil sebya partii.” Kommersant. 16 July 2015.

5 See “Inertsiya Vertikali: Kreml’ teryaet kontrol’ nad regional’nymi elitami” Slon.ru 27 January 2016.

6 See “Deputaty menyayut mast’” Gazeta.ru. 11 August 2016.

7 As is usual in Russian elections, many precincts reported anomalously high turnout. In addition, several well-regarded forensic indicators of fraud were uncovered. For a preliminary analysis see: <external pagehttps://meduza.io/cards/vizhu-mnogo-grafikov-o-falsificall_made external pagekatsii-na-vyborah-chto-oni-znachatcall_made>

8 Ora John Reuter and Graeme Robertson. 2012 “Subnational Appointments in Authoritarian Regimes: Evidence from Russian Gubernatorial Appointments,” Journal of Politics. 74(4).

9 These incentives were present not just in the SMD races. Party list seats are apportioned within-list on a territorial basis. The number of seats that each territorial list receives is determined by the total number of votes for the party in district. Thus, many governors can ensure more representation for their region by increasing UR vote totals on the party list.

10 One of the starkest examples of this conflict was from Samara Oblast. After receiving a bevy of complaints about violations in the oblast—1 in 7 complaints received by the Central Election Commission were from Samara—Governor Merkushkin was harshly criticized by Pamfilova for the use of administrative resources. A team from the Presidential Commission on Human Rights was dispatched to the oblast to meet with Merkushkin.

11 See <external pagehttp://w w w.rbc.ru/politics/11/08/2016/57ab81969a7947c642efdea3call_made>

12 A variant of this approach can also be seen in the familiar slogan “Kto esli ne Putin” (Who, if not Putin?).

Analysis

Elections in Saratov: Numerous Troubling Questions

By Andrey Shenin

Analyzing the Results

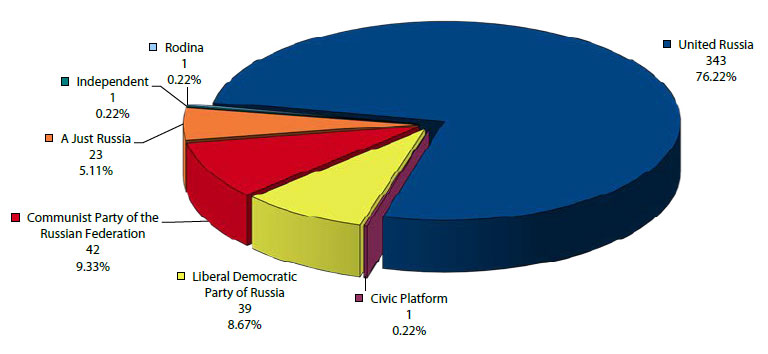

The results of the 2016 State Duma elections did not bring any serious changes to the Russian political environment. The largest political party, United Russia, con- fidently won the race with 54.20% (343 seats), LDPR— 13.14% (39 seats), KPRF—13.34% (42 seats), and Just Russia—6.22% (23 seats). Therefore, the State Duma will consist of the same “usual” political parties that were represented last time. However, this basic outcome does not represent people’s sentiments and the situation on the ground, where black PR, electoral manipulations, and other abuses occurred despite the Kremlin’s stated goal to conduct honest and transparent elections.

In Saratov, many journalists, political consultants and con artists had eagerly awaited the campaign period to earn a share of the money generously put up by parties and candidates, but this year was defined by calm and political apathy. “There were no campaigns, scandals, or even much activity by the candidates. It looks like the ‘right people’ paid for their Duma seats and everybody was well aware of who must be elected where,” one PR- agent said to me.

Another indicator of the low quality of the elections was that the most frequent question asked at the polls was “Who are these people?” Observing the longest lists with 14 parties and more than 8–10 candidates (of 39 as a whole) at every poll, people suddenly realized that they had not seen or heard anything of the contenders. This lack of information applied even to the core of the electorate—retired people—who spend most of their time at home watching TV and collecting rumors about what is happening in their district.

Training for Electoral Observers

My electoral district in Saratov was no. 206, but I also visited no. 202, 204, and 211. Initially, I had planned to take part in the elections as an observer from the Yabloko party and even participated in a training session, but then dropped the idea in favor of observing conditions and activity at several polls. Nevertheless, the training gave me a detailed understanding of current voting procedures and “black technologies,” while the personal experience and testimony of participants provided me with the real situation on the ground.

For example, Mikhail Nikolaevich Gamayunov, one of the training instructors, stressed that there are many tricks to distract observers from ballot boxes, such as the sudden visit of a plumber or children trying to throw extra ballots into a box when it arrives at a disabled person’s home. Accordingly, observer-trainees are instructed that they should ask a police officer to check the documents of any suspicious persons and that they should prepare strips of duct tape in order to stick them over the ballot box in order to protect them against kids’ provocations. Additionally, they learn that the electoral law prohibits using pencils at the polling place because experienced commissioners could put nearly invisible dots opposite the names of people who have not turned out to vote or have recently died in order to add the same number of ballots with the “right” votes marked. Observers must watch all these things, and in fact, they have broad authority that allows them not only to ask to remove pencils from the polling station, but even force an electoral commission to take down the portrait of Vladimir Putin from a wall, because the law considers it to be electoral propaganda in favor of United Russia.

During the training, observers were informed where to position themselves in the polling station, what to do, and what to say. Additionally, they received instructions and an application form required to obtain the final protocol.

At the end of the session, Gamayunov emphasized that even a single observer could force an electoral commission to follow appropriate procedure. However, almost all the trainees were 18–22 year-old female students in the Journalism or Political Science departments of the local university who joined the party mainly for money and had limited experience with the political system. Officially, Russia deployed about 300,000 election observers, but from what I saw of Yabloko’s observers (and observers from other parties at the polls) I seriously doubt that even 10% of those individuals had the necessary skills to ensure that the electoral commissions observed the law.

An ordinary poll (photograph by Andrey Shenin)

Election Day

In my tours of the polls, I heard many reports of falsifications, when electoral commission heads or other individuals stuffed ballot boxes in favor of United Russia during the course of the voting. One of them told me, “I was told that either I guarantee the result, or I will be fired.” Observers, the local police, and other participants clearly realized that everyone was under high pressure to perform. I noticed that observers had no intention to enforce the law and simply were waiting through the day in order to collect the money promised them (1,500–3,000 rubles per day—$25–50). They even declined to comment to journalists about what they had seen, arguing: “we haven't obtained permission to do that.”

Given the apathy of the observers, there was little incentive for officials to comply with the electoral legislation. When one of the observers tried to correct a minor infraction at a poll in Polivanovka (a district of Saratov), she was softly told by the police and commission members “We all have children, we need this job, and we won’t recount the result just for you. If you don’t stop, we will complain about your inadequate behavior to the police—15 witnesses against you alone. You won’t prove anything.” After this, she calmed down and sat quietly until the end of vote counting, satisfied that her candidate won a more or less appropriate total.

Ballot boxes (photograph by Andrey Shenin)

Ultimately, any effort to achieve transparent elections is undermined by the fact that the ballots remain in polling stations for a day or two after the counting process ends. That means that a commission counts votes, delivers the result to observers, wishes them a “good night” and closes the poll. After this, ballots go nowhere and can be falsified in accordance with the set result that had been agreed upon with the local authorities before the voting started.

This year, however, the scheme led to absurd results—almost 100 of Saratov’s 373 polls displayed the same result for the key parties—62.2% for United Russia, 9.1% for LDPR, 11.8% for KPRF, and 6.1% for Just Russia! The head of the Territorial Election Commission Pavel Tochilkin stated that the suspicious results were “a mere coincidence.” Thus, observers and parties have an opportunity to appeal the outcome, but I have not seen anyone among them, in Saratov at least, who were ready to tangle with the courts.

Bulletin (photograph by Andrey Shenin)

The candidates (photograph by Andrey Shenin)

Documentation

GOLOS On Duma Elections: Far From Being Free And Fair

On September 18, 2016, Russia held more than 5,000 elections, including elections of deputies of the State Duma of the Russian Federation, elections of heads of seven regions, 39 elections of deputies of regional parliaments, elec- tions of representative bodies of 11 regional capitals, and other local elections. Public monitoring of the voting pro- cedures, vote counting at polling stations, and tabulation at higher-lever election commissions took place in 40 regions. Considering that, regardless of this year’s reduced coverage of polling stations by independent observers, there were still reports of individual acts of ballot box stuffing, “carousel voting,” voting under pressure, and other irregular- ities, it is evident that these strategies have not been rooted out and are still widely used. However, the September 18 election day was different from the 2011 elections in that there were fewer violations of observer rights (removal from polling stations, restriction of movement at polling stations, bans on making videos and taking pictures) and in that the Central Election Commission (CEC) took quick and principled action in response to these violations. This, how- ever, did not suffice to overcome feelings of distrust and apathy among voters, caused by violations and shortcomings earlier in the election campaign. Overall, the elections of deputies of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation of the seventh convocation are far from being truly free and fair.

In the years since the 2011 elections, the authorities have taken various steps to mitigate and minimize public con- trol over the elections. These steps include the forced inclusion of five “Golos” organizations in the register of the so- called “foreign agents”; the introduction of the 2014 discriminatory amendments to the legislation prohibiting elec- tionobservation by organizations with this status; the ban on foreign funding; obstruction of access to polling stations for observers and the media; persecution of “Golos” organizations and their employees by law enforcement and tax authorities; and information attacks in the federal media. Thanks to the leadership of the CEC in the past six months, the attitude towards public observers and independent experts began to change, but the pressure from the other state organs on “Golos” remained in place.

In 2016, there were half as many independent observers on election day than in 2011.

Observation results from September 18 show widespread use of illegal techniques on election day, although on a somewhat smaller scale than in 2011.

At some polling stations there were direct violations of voting procedures: ballot box stuffing and “cruise voting”; violations associated with pressure exerted by the authorities on voters; illegal campaigning; transportation of voters; violation of observers’ rights as well as rights of commission members and representatives of the media; and violation of counting procedures.

The hotline of the “Golos” movement (8 800 333-33-50) and the service “Map of violations” (<external pagew w w.kartanarushaniy.call_made external pageorgcall_made>) received 1,798 reports of possible violations. These messages were forwarded to the Central Election Commission. Among the most common reports of violations on election day were: violations of absentee voting protocol, viola- tions of “at home” voting protocol, or illegal voting (342 reports); procedural errors (400); violations of observer’s rights, rights of commission members, and rights of representatives of the media (290); illegal campaigning (181); violation of tabulation rules or distortion of voting results (162); violations in the design of polling stations (138); non-inclusion of voters in voter lists or denial of their right to vote (134); coercion of voters or breach of the secrecy of the vote (109). There were reports of ballot stuffing from a number of polling stations in Moscow, Rostov region, Moscow region, Stavropol territory, Voronezh region, Republic of Bashkortostan, Samara region, Kostroma region, Republic of Tatar- stan, Krasnoyarsk territory, Ryazan region, St. Petersburg, Kaliningrad region, Saratov region, Chelyabinsk region, and Republic of Dagestan.

Ballot stuffing in Rostov-on-Don, Nizhny Novgorod, and Krasnoyarsk region were captured on the official live video stream from the polling stations.

Reports of “carousel voting” came mainly from the Altai region and Moscow.

Mass voting with absentee ballots was observed in Moscow. Buses were used to transport voters from one polling station to another. From 70 polling stations came complaints about arrivals of large groups of voters. Even during the election campaign, voters complained of coercion by employers to obtain absentee ballots. There is reason to doubt the voluntary participation of those voters in the elections.

There were reports of cases of illegal campaigning from some regions, particularly from Moscow, Moscow region, and Sverdlovsk region.

In contrast to the 2011 elections, the number of violations related to the (non-)admission of participants into the surveillance areas decreased dramatically. Similarly,the 2016 elections witnessed a decline in the number of cases of illegal removal of participants from polling stations.

At a number of polling stations in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Moscow region, and Saratov, there were cases of artificial delays of the vote counting process, the signing of final protocols, and the issuing of copies of protocols.

On election day, “Golos” reported numerous instances of such violations via various publications, external pagethe chronicle ofcall_made external pagethe voting daycall_made, press releases from regional offices, videos from the call center, and the “Map of violations.”

For more details please see external pagehere (Russian)call_made

Opinion Poll

Election Forcast

Table 1: Levada Center Polls January – August 2016: For Which Party Would You Vote If Elections Were to Take Place Next Sunday?

Source: representative polls by Levada Center, January – August 2016, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/09/01/gotovnost-golosovat-i-predvybornye-rejtingi/>, 1 September 2016

Table 2: VTsIOM Polls June – September 2016: Rating of Parties

Source: representative polls by VTsIOM June – September 2016, <http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=115859>, 12 September 2016

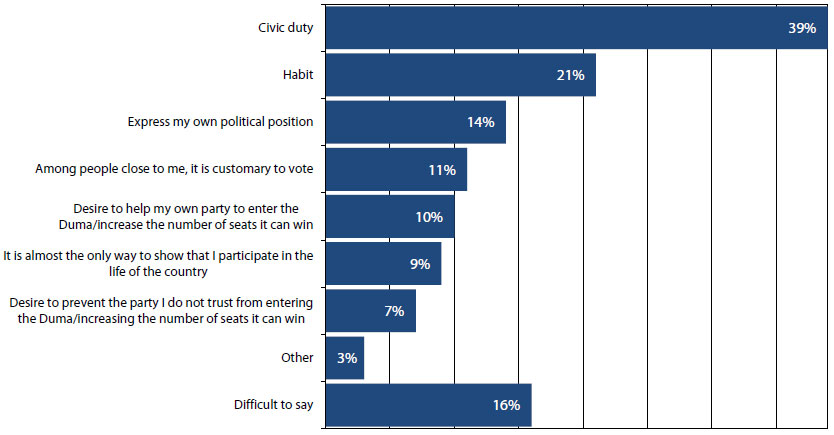

Motivation to Vote

Figure 1: What Would Induce You to Vote?

Source: representative polls by Levada Center, 23–27 June, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/07/12/motivatsiya-uchastvovat-v-v ybo rah/>, 12 July 2016

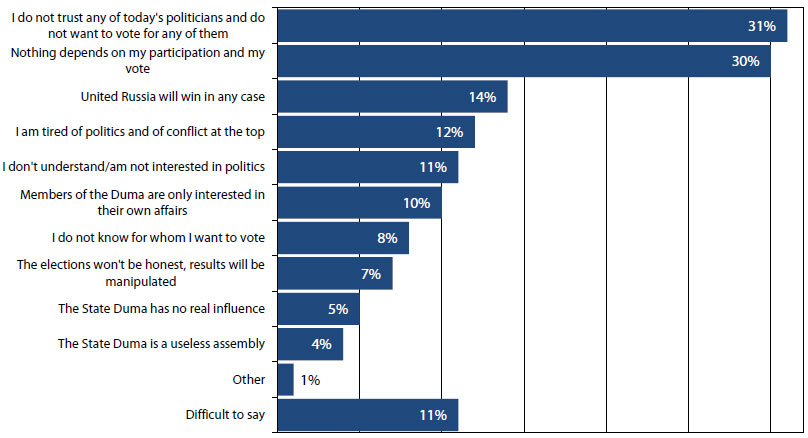

Figure 2: Why Do You Not Want to Vote Or Are Doubtful Whether You Are Going to Vote?

Source: representative polls by Levada Center, 23–27 June, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/07/12/motivatsiya-uchastvovat-v-v ybo rah/>, 12 July 2016

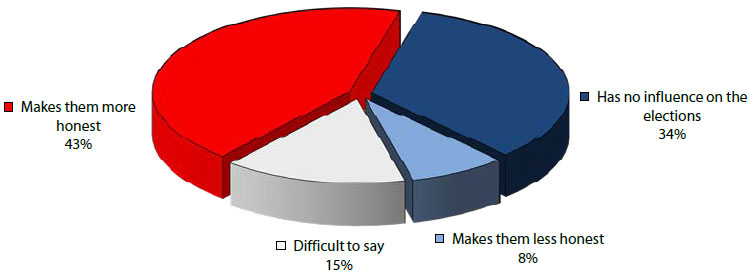

Monitoring the Elections and Electoral Fraud

Figure 1: Do You Think the Presence of Independent Observers in the Polling Stations Makes the Elections More Honest Or Not?

Source: representative polls by VTsIOM, 20–21 August 2016, <http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=115861>, 13 September 2016

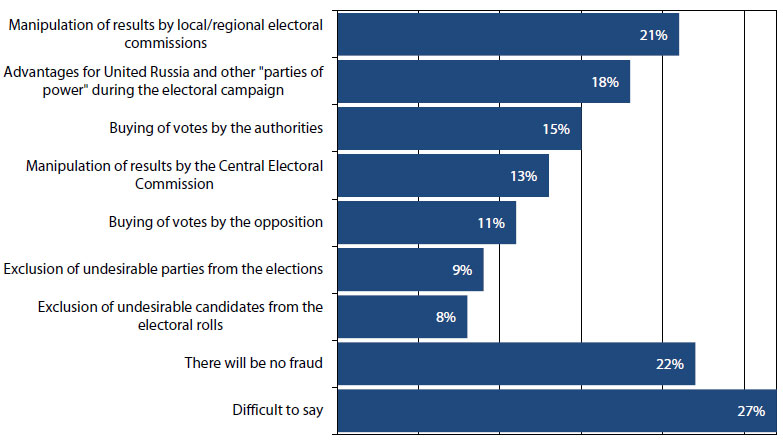

Figure 2: What Do You Think, Will the Following Kinds of Electoral Fraud Occur During the Upcoming Elections? (2016, Multiple Answers Possible)?

Source: representative polls by Levada Center, 5–8 August 2016, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/08/22/ozhidanie-zloupotreblenij-navyborah/>, 23 August 2016

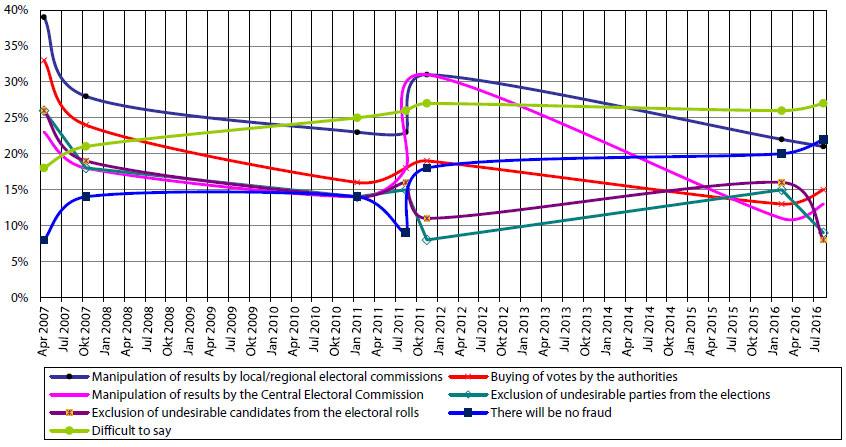

Figure 3: Electoral Fraud 2007–2016 (Expectations According to Polls)

Source: representative polls by Levada Center, 2007 – 5–8 August 2016, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/08/22/ozhidanie-zloupotreblenij-na-vyborah/>, 23 August 2016

Election Results

Figure 1: Seat Composition, State Duma of the 7th Convocation (Party List Deputies and Single Member District Deputies)

Source: <https://rg.ru/2016/09/19/edinaia-rossiia-poluchila-konstitucionnoe-bolshinstvo-v-novoj-gosdume.html>, 20 September 2016

Figure 2: Percent of Votes Cast

Source: Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation, <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action= show&root=1&tvd=100100067795854&vrn=100100067795849®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=0&vibid=100100067795854&type=242>, 28 September 2016

Table 1: Percent of Votes Cast

Source: Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation, <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100067795854&vrn=100100067795849®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=0&vibid=100100067795854&type=242>, 28 September 2016

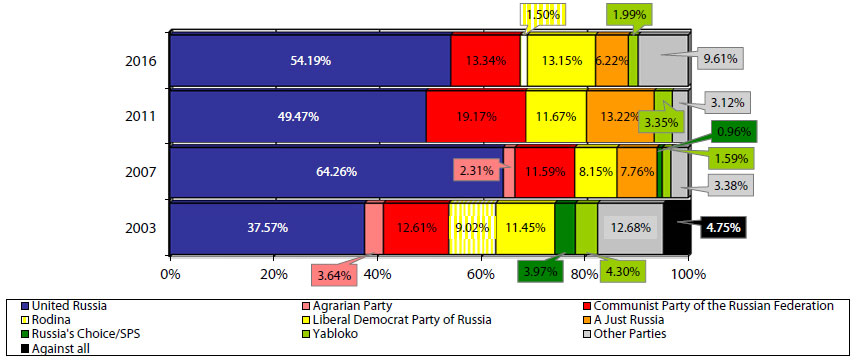

Elections Results and Turnout in Comparison

Figure 1: Results of the Duma Elections 2003, 2007, 2011 and 2016 (Party Lists)

Sources: <http://www.izbirkom.ru/izbirkom_protokols/sx/page/protokol2>, 9 December 2003; <http://www.v ybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100021960186&vrn=100100021960181®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=100100021960186&type=242>, 10 December 2007; <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100028713304&vrn=100100028713299®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=100100028713304&type=233>, 5 December 2011; <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100067795854&vrn=100100067795849®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=0&vibid=100100067795854&type=233>, 28 September 2016

Figure 2: Turnout for Duma Elections 1993–2016

Source: Kommersant, 21 December 1999, p. 1; <http://www.fci.ru/gd99/vb99_int/default.htm> of 23 December 1999; <http://www.izbirkom.ru/izbirkom_protokols/sx/page/protokol2>, 9 December 2003; <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100021960186&vrn=100100021960181®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=100100021960186&type=233>, 3 December 2007; <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100028713304&vrn=100100028713299®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=100100028713304&type=233>, 5 December 2011; <http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/izbirkom?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100067795854&vrn=100100067795849®ion=0&global=1&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=0&vibid=100100067795854&type=242>, 28 September 2016.

About the Authors

Ora John Reuter is assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Andrei Shenin is a Saratov-based journalist with a Ph.D. in History.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.