Global Militarization Index 2016

20 Jan 2017

By Max Mutschler for Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageBonn International Center for Conversion (BICC)call_made in December 2016.

Summary

Compiled by BICC, the Global Militarization Index (GMI) presents on an annual basis the relative weight and importance of a country’s military apparatus in relation to its society as a whole. The GMI 2016 covers 152 states and is based on the latest available figures (in most cases data for 2015). The index project is financially supported by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

With Armenia, Russia, Cyprus, Greece and Azerbaijan, five European countries are amongst the top 10 worldwide. Following the annexation of Crimea by Russia in particular and the continuing conflict in eastern Ukraine, the security situation in Europe has changed. While, for 2015, eastern European states in particular have shown a marked increase in militarization, a similar trend cannot be observed for most western European countries.

Against the background of protracted conflicts in the Middle East, the level of militarization of most countries remains high. Israel is still at the top and Jordan on position four. It will be interesting in the coming years to see how oil prices, which have sharply fallen since mid-2014, will affect the militarization of the Gulf States and their extensive weapons purchases.

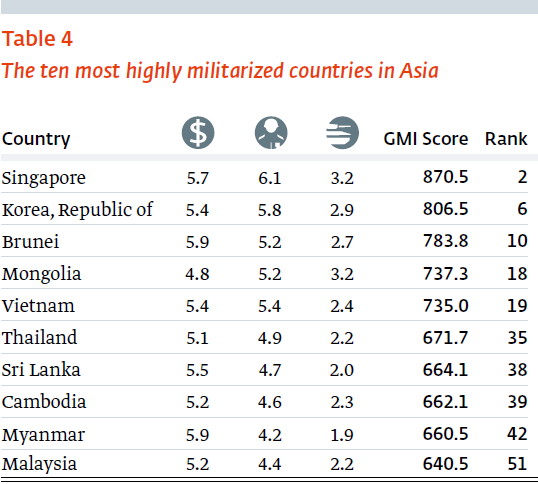

Singapore, South Korea and Brunei are also in the top 10. It remains to be seen how the tensions from the territorial disputes in the South China Sea and connected modernization and armament efforts will shape the level of militarization in Asia.

This year’s GMI highlights the relationship between the level of militarization and the Global Hunger Index, which defines the causes of hunger not only in economic or climate change terms but also with regard to instability or violent conflict. The fact that most states suffering from hunger also have comparatively low levels militarization shows that a low level of militarization often does not point to a peaceful society but more often than not to a weak security sector and the absence of a safe environment. But, within the 20 states that suffer the most from hunger, there are also countries with a relatively high level of militarization. There, high investment is tied up in military resources that would otherwise be available to fight against hunger or to invest in the health system.

The Methodology of the Global Militarization Index (GMI)

The Global Militarization Index (GMI) depicts the relative weight and importance of the military apparatus of one state in relation to its society as a whole. For this, the GMI records a number of indicators to represent the level of militarization of a country:

- the comparison of military expenditures with its gross domestic product (GDP) and its health expenditure (as share of its GDP);

- the contrast between the total number of (para)military forces and the number of physicians and the overall population;

- the ratio of the number of heavy weapons systems available and the number of the overall population.

The GMI is based on data from the Stockholm Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) and BICC. It shows the levels of militarization of 161 states since 1990. BICC provides yearly updates.

In order to increase the compatibility between different indicators and to prevent extreme values from creating distortions when normalizing data, in a first step every indicator has been represented in a logarithm with the factor 10. second, all data have been normalized using the formula x=(y-min)/ (max-min), with min and max representing, respectively, the lowest and the highest value of the logarithm. In a third step, every indicator has been weighted in accordance to a subjective factor, reflecting the relative importance attributed to it by BICC researchers (see Graph below). In order to calculate the final score, the weighted indicators have been added up and then normalized one last time on a scale ranging from 0 to 1,000. For better comparison of individual years, all years have finally been normalized.

The GMI conducts a detailed analysis of specific regional or national developments. By doing so, BICC wants to contribute to the debate on militarization and point to the often contradictory distribution of resources.

BMI GMI in 2016

A tendency towards rearmament has been observed in many regions of the world. Even in Europe, where a decline in defence budgets was recorded for a long time, the conflict in Ukraine has led to a change in thinking. In 2015, a significant increase in militarization was apparent in eastern European countries. However, a similar trend was not yet apparent in most western European countries. As before, most states in the Middle East boast high levels of militarization. Israel, which has been in a decades-old conflict with its neighbours, continues to lead in this respect, not only in this region but also worldwide.

The states’ different threat perceptions essentially determine the setup and equipment of the armed forces. In principle, the initial conditions and triggers for armament or modernization—and thus the change in the level of militarization—vary greatly from country to country and even from region to region.

Militarization remains a controversial concept. BICC’s Global Militarization Index (GMI) is deliberately designed to avoid the normative assumption that militarization always means an excessive emphasis on military power, or that a high allocation of resources for the military generally has a negative impact on security or the development of society as a whole. In reality, a low level of militarization may also indicate issues, such as the problem of fragile statehood. The GMI therefore puts the allocation of resources to the military in the context of the wider society, for example, military spending in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) and public spending on health (share of GDP). This also allows the militarization of a country to be linked to other benchmarks, such as the Human Development Index, see GMI 2015 (from page 10), or the Global Hunger Index.

In the following text, the GMI presents and analyzes selected trends in militarization. Most of the data relates to the year 2015.

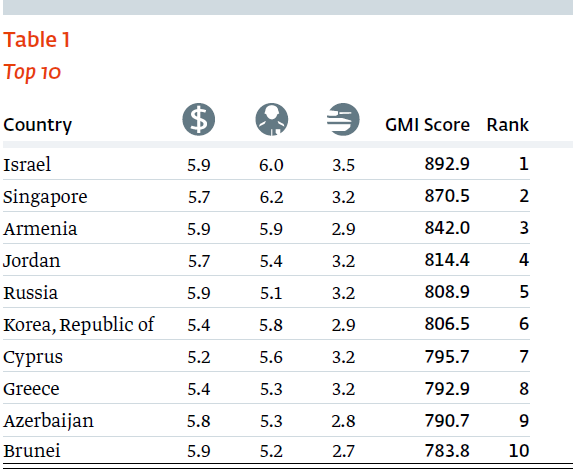

The Top Ten

The ten countries that have the highest levels of militarization for the year 2015 are Israel, Singapore, Armenia, Jordan, Russia, South Korea, Cyprus, Greece, Azerbaijan and Brunei. These countries allocate particularly high levels of resources to the armed forces in comparison to other areas of society.

In previous years, Syria was always in one of the top spots. Due to the civil war no reliable statements can be made now—and indeed for several years— about the resources of the government’s armed forces. However, it is assumed that the country’s level of militarization is very high and has increased even further by the war.2

It may at first glance cause irritations that militarily dominant countries such as the United States (position 31) or China (position 91) are not found within the top 10. After all, both countries invest huge sums in their military apparatus and maintain big armies in terms of personnel. US military spending was around US $ 595 billion in 2015.3 No other country invests as much money as this in its military. Even the Chinese military expenditure for 2015—more than US $ 214 billion—is not half that amount. Here it should, however, be noted that China’s military spending has gradually increased in the last three years, while the United States’ has gradually decreased. However, these high values are put into perspective when compared to the GDP or the total population of the United States or China. This explains conversely, why for years small countries such as Singapore, Armenia or Cyprus are to be found in the world’s top 10 in the GMI.

Compared to last year, there are only minor changes in the top ranks. Russia (now position 5) and South Korea (now position 6) swapped places. Greece rose from 10th to 8th place, Azerbaijan fell from 8th to 9th. The 10th position now belongs to Brunei (last year it was number 11).

Focus on Regional Militarization

Europe

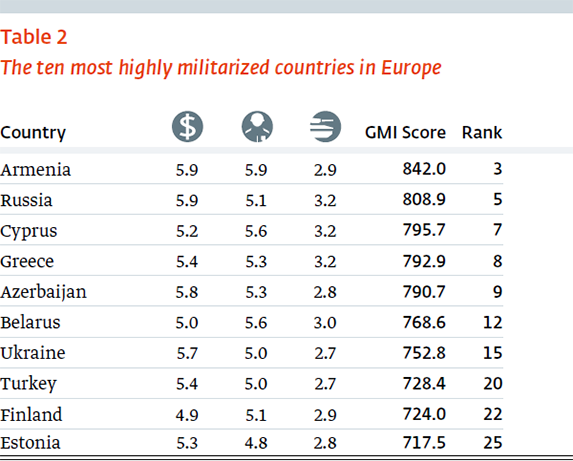

Top rankings in Europe

Not much changed in the top positions in Europe in 2015. Armenia, Russia and Cyprus are in positions one to three, as was the case in the previous year. In the fourth and fifth place Azerbaijan and Greece simply exchanged spots. Ukraine and Turkey climbed one place up each (position 7 and 8), while Finland slipped down two places (position 9).

As in previous years, the very high levels of militarization in Armenia (position 1) and Azerbaijan (position 5) stand out. This primarily reflects the ongoing conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. Both countries invest an excessive amount of resources in their armed forces. That the situation is still tense was underlined by the military clashes in April 2016, in which at least 110 soldiers and civilians were killed on both sides and which were the heaviest fighting since the ceasefire in 1994. The current efforts of the Minsk Group under German OSCE Chairmanship to mediate in the conflict have so far not produced any results. As the failed coup attempt in July 2016 shows, the domestic political situation in Armenia is also tense.

Despite its continuing economic problems, Greece also continued to invest comparatively high levels of resources into its military. Among other things, the very high number of heavy weapons compared to the population size is striking.

For several years Belarus has held one of the top positions in Europe. In the authoritarian country, although the ratio of military expenditure to GDP is not particularly high at 1.2 per cent, the amount of military personnel and heavy weapons is.

Eastern Europe

Following the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the continuing conflict in eastern Ukraine, the security situation in Europe has changed. It is not surprising that Ukraine significantly increased its level of militarization since Russia annexed Crimea. Thus, military spending rose from US $ 3.3 billion (2013) to US $ 4.4 billion (2015). The number of military and paramilitary personnel increased significantly from 2014 to 2015. Thus, Ukraine climbed in the overall ranking from 23rd place in 2015 to 15th position in 2016. It is likely that the increase in military spending in the coming years will also have an impact on the procurement of heavy weapons. After the collapse of industrial cooperation and trade with Russia, it is likely that strengthening the national defence industry, including the development of cooperation opportunities with new partners, will be an important objective in Ukrainian politics.

Since 2001, Russia has continuously been in the global top 10 of the GMI—in fifth place in 2016. Aside from the relatively high number of military personnel, the very large number of heavy weapons systems in particular decided its position. Both quantities—for military personnel as well as the heavy weapons—have remained fairly constant over the past few years. There was a clear increase in military expenditure, from US $ 84.7 billion in 2014 to just over US $ 91 billion in 2015. These funds are expected to flow into Moscow’s plans to continue to modernize its army and close any gaps in capability with the United States that still exist. Russian military spending and hence the investment in armament projects has, however, come under increasing pressure in the wake of the poor economic situation in Russia and, in particular, as a result of falling commodity prices, so that the planned expenditure for 2016 has already been reduced and further reductions are under discussion.

The Russian annexation of Crimea and the continuing tense situation in eastern Ukraine have had an impact on the militarization of many EU countries. The long-term trend of declining defence spending initially ground to a halt and is in the process of being reversed. In particular this was already apparent in 2015 in the eastern European countries. All three Baltic states increased their military spending between 2013 and 2015. In Lithuania, for example, it increased from US $ 355 million in 2013 to US $ 427 million in 2014 and continued to US $ 566 million in 2015. In Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, military expenditure also rose in 2015.

For all states mentioned thus far, the GDP has declined at the same time as military spending increased from 2014 to 2015; Poland’s GDP, for example, fell from US $ 544.9 billion in 2014 to US $ 474.8 billion. This combination of increasing military spending and decreasing GDP led to an increase in the level of militarization for those states and thus also to most eastern European EU countries having higher positions in the 2016 global GMI ranking. This increase is most pronounced in Lithuania, which moved up from position 60 (GMI 2015) to number 44 (GMI 2016).

In Lithuania in particular, the level of militarization could increase even further in the coming years. Because of the Ukraine crisis the country temporarily re-introduced conscription in March 2015, which had been abolished in 2008. The number of troops is expected to increase annually and a reserve to be established through a nine-month basic military training for up to 3,500 people.

It is expected that this trend of rising military expenditures in eastern European countries will also continue in the coming years. A study by several European think tanks forecasts that in the 31 European countries studied, defence spending in 2016 will increase on average by 8.3 per cent compared to 2015. This is mainly due to the significant increase of 19.9 per cent in the central and eastern European states in the study. The expected growth in 2016 for the western European countries is 2.7 per cent compared with the previous year.4

The increase in military spending is likely to have an impact on the armament projects of those states. Some eastern European and south eastern European EU countries got new procurement projects off the ground. They strive to make themselves more independent from Russia with respect to the supply of military equipment, by parting from older, Russian weapons systems, which partly even came from the Soviet era, and modernizing their military. Romania has, for example, bought F-16 fighter aircraft from Portugal—aircraft that have already been in use by the Portuguese Air Force— to replace the Russian MiG-21. Poland, in turn, is planning to replace large parts of its Russian-made military helicopter fleet. It is to be expected that in the coming years Poland will invest in the modernization of its military, and that Western defence companies in particular will get the opportunity to do business with them. The same is true for the three Baltic states. For example, in October 2016 Estonia received the first 12 (of 44) CV90 infantry fighting vehicles from the Netherlands.

Western Europe

In contrast to eastern Europe, no significant increase in militarization was observed in most western European countries in 2015. In large countries like Germany (position 100), France (60), Great Britain (71), Italy (81) and Spain (92), the GMI values even fell slightly compared to the previous year. The militarization figures in western Europe do not therefore yet reflect the changed security situation in Europe. However, it is likely that this will alter in the coming years. It is already expected that for 2016 defence spending in western European countries will slightly increase by 2.7 per cent compared to the previous year.5 Some states have already announced further increases for the coming years. In this way, Germany plans to increase its defence expenditure by 6.2 per cent between 2015 and 2019. In France after the terrorist attacks on 13 November 2015, an additional 3.8 billion euros was released for defence planning until 2019. It is also expected that the United States will insist that European NATO states invest more in their military to achieve its goal of defence spending making up two per cent of GDP. Under the future US president Donald Trump, this pressure is likely to increase further.

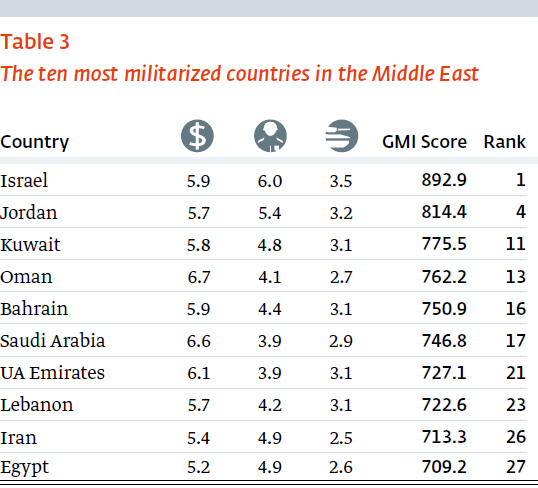

Middle East

The list of the ten most militarized countries in the Middle East has hardly changed since last year. Israel is still at the top. Here, in particular, the very high number of military personnel that is reflected in the GMI is due to the Israeli system of compulsory military service. Israel has also outpaced the other countries in the region in terms of the ratio of heavy weapons to the total population. Although Israel has a powerful defence industry, it repeatedly invests resources in importing the most modern weapons systems such as the F-35 stealth multirole fighter from the United States.

The driving force behind Israel’s high militarization is the decades-old conflict with its neighbours. Like most countries in the Middle East, these states also have a high level of militarization. In Egypt, for example, military expenditure had almost continuously declined in the years before 2013. However, following the military coup in 2013, it again significantly increased from US $ 46.6 billion in 2013 to US $ 53.6 billion in 2015. The current poor economic situation does not seem to have had an effect on this. The same also applies to the procurement of new weapons systems. In addition to the purchase of 24 Rafale fighter jets from the French manufacturer Dassault, the modernization of the Egyptian Navy is a major cost factor. Thus, in June 2016 the first of two French Mistral helicopter carriers, which were once originally intended for Russia, were delivered. Egypt has also ordered four Type 209 submarines from Germany.

It will be interesting in the coming years to see how oil prices, which have sharply fallen since mid-2014, will affect the militarization of the Gulf States, which have very high military spending when compared internationally.6 This has precipitated massive arms purchases in recent years, financed mainly by means of the revenues from the oil business. If oil prices remain low, these states need to decide whether to reduce their high military spending or make cuts in other areas. The latter could be problematic for the authoritarian regimes in the Gulf, because their legitimacy is also based on the subsidization of social services and the provision of jobs in the state apparatus. To date, however, there has been no indication that military spending will be reduced. This applies especially to Saudi Arabia, which has significantly and continuously increased its military expenditure since 2011 in absolute terms as well as in relation to GDP. Defence spending in the kingdom makes up 13.7 per cent of GDP, which is extremely high even for the Middle East.

Asia

In Asia, the list of the ten most militarized countries has hardly changed compared to last year. South Korea ranks second after Singapore, whose military is equipped with modern weapons systems and is very large considering its total population size. A significant factor in South Korea’s militarization was and still is the ongoing conflict with North Korea7, which continued to intensify as a result of North Korea conducting nuclear weapon and missile tests in 2016. South Korea’s military spending has risen moderately and continuously in recent years, and they also plan to continue to increase it until 2020. Its share of GDP is relatively constant at 2.6 per cent. These resources will be invested on the one hand in obtaining a sizeable military and, on the other, in arms procurement, which has been particularly focused on the navy in recent years. South Korea is also spending funds on building a missile defence system, which is directed at the threat of North Korean missiles. Here, South Korea cooperates closely with the United States. In July 2016, the plan was confirmed to deploy the United States’ mobile, land-based anti-ballistic missile system Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) in South Korea. South Korea is also expanding its sea-based missile defence in cooperation with the United States. Three more ships are to be added to the existing fleet of three destroyers equipped with the Aegis missile defence system.

The tensions from the territorial disputes in the South China Sea are so far not reflected by a significant increase in the level of militarization of the countries concerned. The GMI values of China (position 91), Indonesia (90), Vietnam (19), the Philippines (105) or Japan (102) have remained fairly constant over the last few years. But it cannot be ruled out that this will change in the future. For not only China, but also other countries in the region, such as Vietnam, are modernizing their navy. From 2011 to 2015, Vietnam was ranked eighth in the global importers of major conventional weapons. The majority of them came from Russia; the cooperation will intensify in the coming years. Yet another interesting feature is likely to be, what impact the complete lifting of the United States' arms embargo against Vietnam, as announced in May 2016, will have on this. The embargo has existed since the end of the Vietnam War.

Australia (position 64), too, announced in its most recent defence white paper (published in February 2016) that it would be significantly upgrading its fleet. This includes the planned purchase of 12 new submarines. These and further armament efforts will be financed by increasing the proportion of defence spending from 1.9 percent of GDP in 2015 to two per cent by 2020/21.

Militarization and Hunger

The GMI highlights which countries spend a great deal or very few resources on their military. The Index does not have a normative approach, that is, it does not contain in itself any evaluation about what a high or low militarization means for the society in question. Of course, funds that are invested in the military might be lacking elsewhere, such as in health and education, or in investments in more productive economic sectors. Conversely, however, a low level of militarization does not necessarily mean a peaceful society. On the contrary, it may be indicative of a weak security sector and a correspondingly insecure environment in which domestic armed conflicts, civil wars and rebellions take place. Also the connection between hunger in a country and its militarization is far from clear, as a brief comparison of the current GMI and the 2016 Global Hunger Index (GHI) shows.8

The GHI is calculated each year by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and serves to illustrate the hunger situation at global, regional and national levels. The GHI 2016 concludes that the level of hunger in developing countries has fallen by a total of 29 per cent since 2000. Nevertheless, the hunger levels are still serious in many countries. Sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries are particularly affected.

If we look at the 20 countries in which the hunger situation, according to WHI 2016, is the worst in the world, we can conclude that the majority of these countries have comparatively low levels of militarization.9 This is even clearer when looking at the seven countries that according WHI 2016 still suffer from “very serious” hunger: Haiti, Yemen, Madagascar, Zambia, Sierra Leone, Chad and the Central African Republic have the worst levels of hunger. With the exception of Chad (position 68), all these states, for which we have valid data—Zambia (position 99), Madagascar (position 136), Sierra Leone (position 146)—have a relatively low level of militarization.10 This finding appears to support the explanation of the WHI 2016 that in addition to economic or climatic causes, hunger is often explained by political developments, in particular by instability and violent conflicts, which are usually accompanied by massive refugee movements. So, a low level of militarization can also be an indication of fundamental shortcomings in the security apparatus, in which case the safe environment necessary for economic and social development is absent.11 This is usually the case, particularly in countries with a past civil war, such as Liberia (position 149) and Sierra Leone.

This does not mean, conversely, that greater militarization automatically leads to more stability or even less hunger. This is illustrated by the fact that within the 20 states that suffer the most from hunger, there are also countries with a relatively high level of militarization; in addition to Chad (position 68), these include Namibia (position 46), Pakistan (52) and Angola (37), which is the most militarized state in Sub-Saharan Africa. The proportion of military expenditure to GDP has most recently declined significantly (from 5.2 per cent in 2014 to 3.5 per cent in 2015). But still there is a danger that too much investment is tied up in military resources, and therefore not available to fight against hunger or to invest in the health system. For every 10,000 Angolan inhabitants, there are 48 soldiers (including paramilitary forces), but only one physician.12

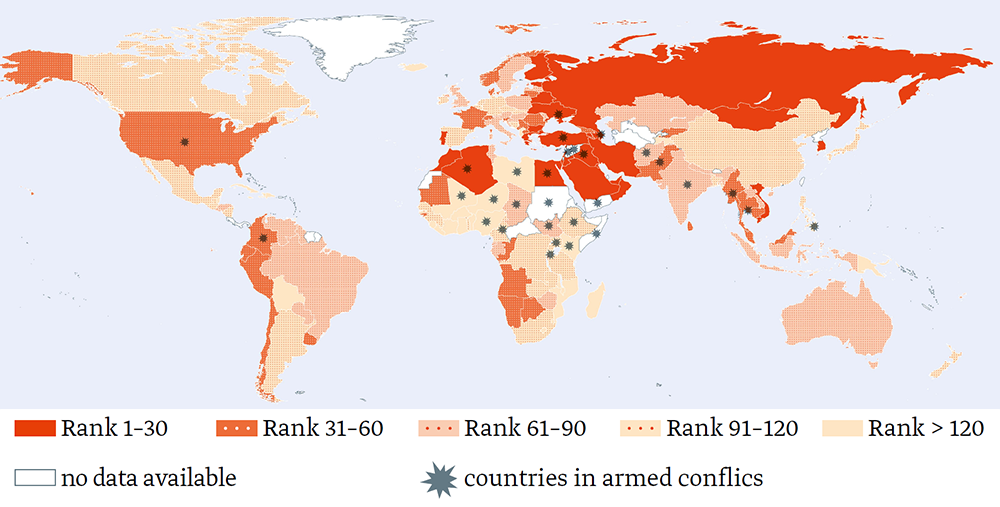

Map 1: Overview GMI-ranking worldwise

The depiction and use of boundaries or frontiers and geographic names on this map do not necessarily imply official endorsement or acceptance by BICC.

Notes

- The main criterion for coding an organizational entity as either military or paramilitary is that the forces in question are under the direct control of the government in addition to being armed, uniformed and garrisoned.

- No reliable information is available for other states, such as North Korea and Eritrea. However, it is assumed that at least in these two countries, there is also a high level of militarization.

- Unless otherwise indicated, all information on military expenditure in this publication has been taken from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database.

- Marrone, A., De France, O., & Fattibene, D. (Eds.) (2016). Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers.

- Op. cit.

- We have not had any reliable figures for military spending in Qatar since 2010. In 2015, we have no reliable data for Yemen.

- North Korea is probably very heavily militarized. There is, however, no valid data available.

- Welthungerhilfe, Internationales Forschungsinstitut für Ernährungspolitik (IFPRI) and Concern Worldwide (11 October 2016).

Welthunger-Index 2016. http://www.welthungerhilfe.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Themen/Welthungerindex/WHI_2016/Welthunger-Index-2016-Hunger-beenden-Welthungerhilfe.pdf - 10 of 15 states (for five countries—Central African Republic, Haiti, Djibouti, Yemen and Zimbabwe—we do not have any valid data) have a GMI-value of less than 550 and—with the exception of Zambia (position 99)—have a three-digit GMI ranking.

- For the Central African Republic, Yemen and Haiti, we do not have any valid data.

- Last year’s GMI publication already took a closer look at the links between militarization and human development. See Grebe, J., & Mutschler, M. M. (2015). Global Militarization Index 2015. Bonn: BICC, pp. 10–11.

- As a comparison: In Nigeria, for every 10,000 inhabitants there are nine soldiers (including paramilitary units) and three physicians.

About the Author

Dr. Max M. Mutschler is a Senior Researcher at BICC and the Co-Editor of the German Peace Report.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.