The Putin System

9 Apr 2018

By Jeronim Perović for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in April 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Vladimir Putin has dominated Russian politics for nearly two decades. On 18 March 2018, the president was re-elected for another six years, winning nearly 77 per cent of votes cast. The “Putin System” is not geared towards urgently needed economic and social reforms, but mainly serves to cement existing relations of power.

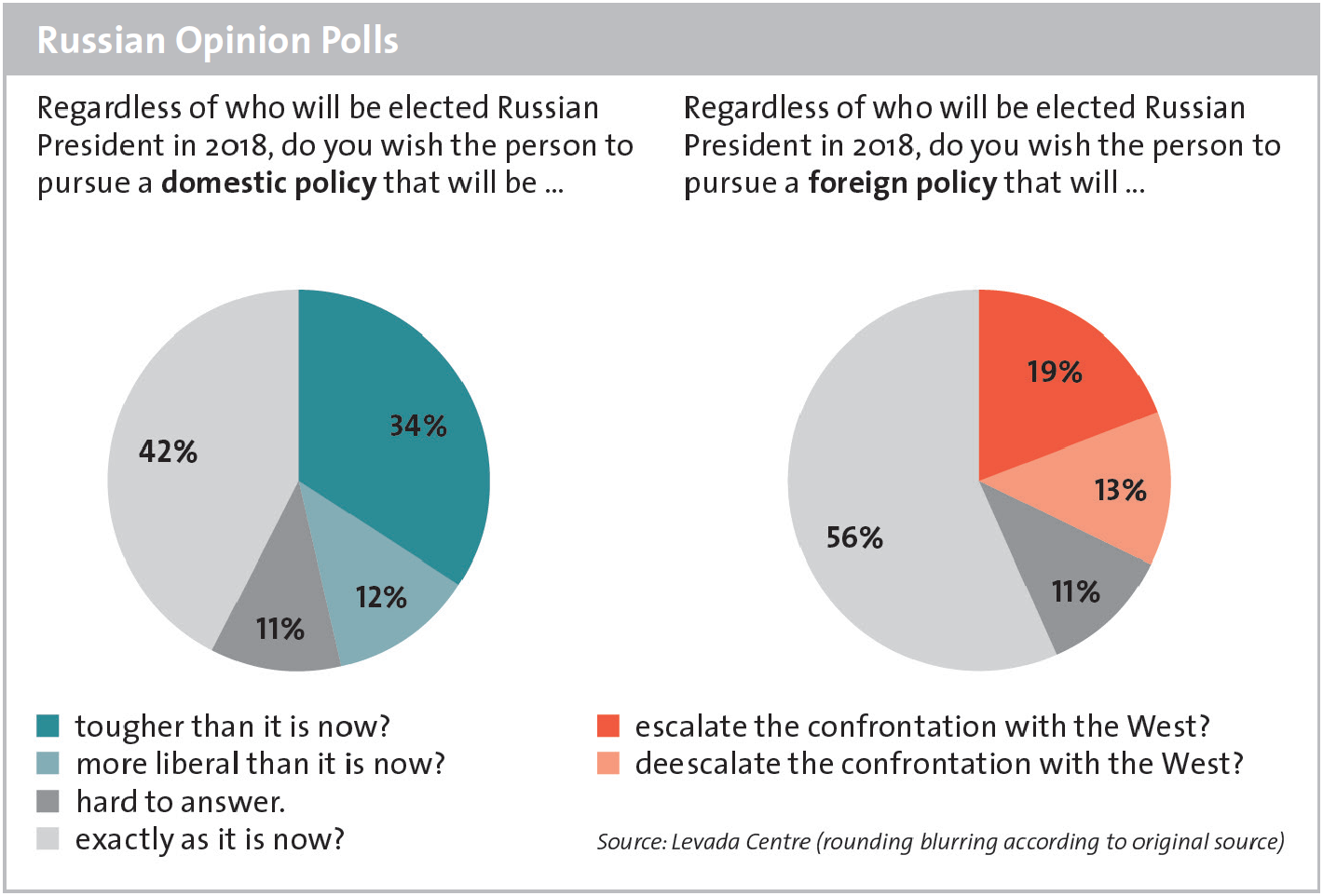

Putin’s electoral victory has come as no surprise. Support for the president and his policies has been high for many years, despite the Russian economy chafing under Western sanctions and low oil prices. Interestingly, not only is support for Putin quite high, but surveys show that a majority of the Russian population backs the Russian leadership’s current course in domestic and foreign affairs or even supports a tougher stance – regardless of who rules Russia as president (cf. graphic below).

It would be too simplistic to attribute these high approval rates solely to official propaganda, which is spread primarily via state television. For years, every channel has extolled the myth of Putin as the supposed “savior” of a Russia that only recovered from the decline of the 1990s thanks to him. There is a widespread notion of Russia as a “humiliated” country that, thanks only to Putin’s firm hand, has managed to rise again and once more actively assert its legitimate interests on the global stage. These narratives work not only due to propaganda, however. They are persuasive because they strike a chord with the population and because many Russians, based on deeply held convictions, share the views that the state is promoting.

In this respect, the economic sanctions imposed by Western states in 2014 have actually played into the hands of the regime. For Moscow, they only offer further confirmation that Western policy ultimately aims at weakening Russia. The sanctions, it is argued, are part of a larger strategy to bring about a regime change in Russia itself. Of course, Russians want prosperity and a better life. However, it appears that in order to sustain Russian great power ambitions, a majority of the people are willing, at least temporarily, to tighten their belts and accept the cutbacks imposed by the difficult economic situation and the budget reductions to healthcare, education, and pensions.

Fear of Revolutions

The result of the 18 March 2018 election also revealed that despite all the government’s mobilization efforts, more than 32 per cent of eligible voters abstained from casting their ballot. In many cities and regions, notwithstanding heavy police presence, there were even public protests against Putin in the run-up to the polls.

Even though the potential for protest currently appears to be very small, and liberal-minded politicians have hardly any support among the population (they two liberal presidential candidates, Ksenia Sobchak and Grigory Yavlinsky, together won less than three per cent of all votes), the country’s leadership is nevertheless extremely sensitive regarding any manifestations of discontent. Long before the “Euromaidan” of 2013/14, the Kremlin has been aware that seemingly innocuous protest movements can always develop unforeseen dynamics, especially in times of crisis. Before the crisis in Ukraine, there had been a series of portentous developments – the “Rose Revolution” in Georgia (2003), the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine (2004), and the “Tulip Revolution” in Kyrgyzstan (2005). In all of these countries, street protests had overthrown the elected governments. The Kremlin was also able to study the potential momentum that mass movements can achieve in the “Arab Spring” from 2011 onwards, which in some cases led to peaceful regime change, in others to chaos and civil war.

Ever since, the Russian leadership has responded aggressively to protests inside the country. The large-scale anti-government demonstrations of 2011/12 marked a turning point. They were set off by irregularities discovered in some regions during the Russian parliamentary election, which led to demonstrations involving tens of thousands of protesters. Demonstrations took place not only in major cities like Moscow and St Petersburg, but in many smaller cities, too, thousands took to the streets protesting against fraud and the country’s leadership.

These protests movements, which continued for several months, did not pose a serious threat to the stability of the regime. The government rallied massive police forces to break up the demonstrations and had hundreds of participants arrested. Nevertheless, the Kremlin was caught by surprise by the scale of the protests, the tenacity of the participants, and the high mobilization potential within society. At the same time, to those in power, the events indicated that there were limits to the state’s arbitrary policies. Even in authoritarian states, people seem unwilling to tolerate election manipulation or obvious corruption and abuses of power. According to surveys, many Russians today view corruption in particular as one of their country’s greatest scourges.

Enhanced Repression

Since these events, the state authorities have not only turned up the rhetorical heat even further. Suppression of the remnants of the political opposition and societal organizations operating independently of the state has also increased recently. In particular, the law on “foreign agents” introduced in 2012 has been used to raise the pressure on NGOs and private academic institutions significantly. Some of these have even been forced to shut down completely in recent years. Thus, even the well-known “Levada Center”, the last independent polling organization, has been severely harassed by the state authorities since September 2016, when the government listed it as a “foreign agent”, claiming that it received funding from the US.

At the same time, the Kremlin is working harder than ever to establish a “national consensus”, not least by instilling a patriotic view of history in the general population. To this end, schoolbooks are rewritten, and the Kremlin supports foundations and internet portals that propagate the state-sanctioned historiography. Already in May 2009, the then president of Russia, Dmitry Medvedev, appointed a commission to counter attempts at “falsifying history to the detriment of Russia’s interests”. Under Russian law, the state authorities are empowered to prosecute dissenting opinions, for example when it comes to assessing the role of the Soviet Union in the Second World War.

While the internet remains a largely free domain in Russia, the law also permits the state authorities to move rigorously against critics in this sphere by shutting down opposition websites. For example, in February 2018, the website of well-known Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny was blocked after he had posted a video exposé of a corruption case involving a high-ranking state official. The demonstration laws have also been tightened: The security forces now even have permission to open fire on crowds at their own discretion.

The government rhetoric and the increasing repression betray the sensitivities of a regime that feels threatened, despite high approval rates. For Putin, the mass demonstrations of 2011/2012 were an ominous development: The people were taking to the streets not due to immediate economic distress, but in order to protest against state-sanctioned election fraud. This placed Putin’s system of power under severe strain.

A Stress Test for the Putin System

One important factor in Putin’s consolidation of power has been the fact that the Russian state, following the largely chaotic privatization of the 1990s, managed quite rapidly to regain control of the commodities sector and other strategic economic assets and to roll back the influence of the formerly powerful oligarchs. This is significant because only a few dozen corporations account for the lion’s share of Russia’s national economic output. Currently, companies from just 12 key sectors generate over 90 per cent of the revenues of the 500 largest Russian corporations. This means that power in Russia is concentrated among those who control these key sectors. Among these 500 important businesses, the oil and gas companies alone are responsible for over 30 per cent of turnover and nearly half of total profits. Currently, the oil and gas sector generates about the same profit as the five next-largest economic sectors combined.

Due to the sustained depression of oil prices, however, the oil and gas companies have generated considerably lower revenues in recent years, with immediate effects on the federal budget: While the state until recently depended on the oil and gas sector for about half of its tax revenue, that share had diminished to 40 per cent in 2017. Russia has been falling back on its National Wealth Fund to balance the budget deficit, and the devaluation of the ruble relative to the US dollar (the trade currency in the oil business) has helped to soften the blow of the oil price crash. Nevertheless, revenues from commodities exports have declined, and there is less rent available for redistribution. The effects are felt particularly acutely in the area of social services (including pensions, education, and healthcare). Taking inflation into account, there is currently far less funding available for welfare than in previous years. At the same time, due to the poor economic climate among other factors, real wages have also declined in Russia over the past three years. About two thirds of the working population currently receive salaries that are below the country’s average wage level, indicating that the pay gap is also broadening.

There have also been cutbacks in the defense sector, though it is unclear to what extent. According to official numbers, in 2017, the government spent about 25 per cent less on the military than in the previous year. However, real expenditures are likely to be much higher, since some of the defense funding is “hidden” among other budget items or classified. It is believed that the government earmarks about one third of its budget for the area of “security”, which includes not just expenditures on the military and the military-industrial complex, but also the cost of police and various other security and intelligence services. Despite the depressed economic climate, that share is unlikely to decline in the coming years, while it is doubtful that the state will agree to raise expenditures on social programs and civilian projects in difficult economic times.

Preserving Existing Structures

The “Putin System” can only function if existing power structures are maintained. Therefore, the regime is investing in defense and the security apparatus and going to great lengths to control key sectors of the economy via elites loyal to the state. Conversely, as beneficiaries of the system, the country’s economic elites are seeking the proximity of the political power center more than ever, since their own survival is tied to the resilience of the system. In the medium to long term, the authorities will have to consider ways and means of reducing Russia’s dependence on exports of raw materials. However, at the current point in time, those in power are unlikely to welcome reforms aimed at strengthening those sectors of the economy not directly controlled by the state, such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Nevertheless, support for SMEs would be an urgently needed step towards diversifying Russia’s economy, where they currently only contribute about 20 per cent of GDP – much less than in most Western states, where their share of value creation stands at significantly over 50 per cent.

Mobilizing the full innovation potential of Russian society would require not just strengthening the rule of law, but also abolishing bureaucratic hurdles, waging a more determined campaign against corruption, and making loans available to SMEs. However, the real problem with effective diversification is that under the existing “Putin System”, there is no place for a large flourishing private sector. If the prime directive is to preserve a system in which political power equals control of the economy, then the state can have no real interest in fostering a sector consisting of private SMEs, which due to its very structure would be much more difficult to control than a few dozen large corporations and loyal oligarchs. In the “Putin System”, society itself is the main uncertainty factor, and the state intends to control it as far as possible to stave off any contingencies.

The Significance of the Ukraine Crisis

In this context, the eruption of the Ukraine crisis was not inconvenient for the Kremlin at the time. Certainly, the aggressive Russian behavior towards Ukraine should also be understood as backlash against Ukraine’s rapprochement with the West and Kiev’s refusal to join the Moscow-dominated Eurasian economic integration project. The prospect of Ukraine one day joining NATO or the EU has always been the worst-case scenario from Moscow’s perspective. Looking further, however, one should not underestimate the domestic importance of the Ukraine crisis. Among the Russian population, the absorption of Crimea into the Russian state federation has been hugely popular. At the same time, the Kremlin’s propaganda machine has very skillfully exploited the conflict in eastern Ukraine to paint an image of chaos and civil war in the neighboring country. The Kremlin has portrayed the Maidan events as a movement controlled by Western actors, ultimately leading to a “putsch” and power grab by forces dominated by “fascists”. In this way, the Ukraine revolution was denied any form of democratic legitimacy, while the West was accused of trying to “divide” the Russian and Ukrainian “fraternal peoples”.

In this way, the Kremlin hopes to demonstrate to its own citizens the destructive potential of revolutions. Whenever the Russian state takes action against domestic protestors and critics, it justifies this by arguing that it is limiting the influence of external forces hostile to Russia. Only against this domestic background can the Kremlin’s reluctance to play a constructive role in resolving the conflict in eastern Ukraine be properly understood. Moscow has no interest in seeing Ukraine succeed, since this would contradict the official Russian narrative of a misguided Ukrainian national project and question Russia’s own development model.

Strong President, Strong Russia

Only a “strong president” can guarantee a “strong Russia”, according to one of Putin’s election slogans. However, this “strength” as understood by the regime does not consist in the ability to innovate, implement reforms, or engage in self-criticism. The main aim is the preservation of power. To this end, the president relies fully on the loyalty of the people surrounding him. This is likely why Putin has tended in recent years to recruit young, largely unknown officials for his staff and to appoint new people to important government posts. He has also had a number of regional governors replaced in the recent past. This is intended to strengthen the “power vertical” from the top down, minimizing the danger of potential partisan infighting within the governmental and administrative bodies of the state.

Measures to unify the country’s political leadership have coincided with efforts to reinforce national cohesion. With this goal in mind, the regime has kept the entire society in a kind of state of emergency for years by stoking fears of foreign bogeymen and employing increasingly aggressive rhetoric designed to appeal to citizens’ patriotism. In this way, supporting the president becomes the duty of each citizen, and a vote for Putin signifies a vote for a strong and unified Russia.

Putin’s recipe for retaining power has been a success: In March 2018, he was re-elected as Russian president without having presented any sort of tangible election platform. Apparently, most people in Russia are not keen to see radical changes. At the same time, this does not preclude them from hoping for a better and more prosperous life. Opinion polls commissioned just before the election show that even within society at large, there is no consensus on the steps required to achieve a change for the better. Putin’s high approval rates are not necessarily evidence of optimism regarding the future, but simply indicate that voters see no alternative to him at this point. Support for Putin means support for stability and the desire to preserve national cohesion in the face of external threats and a domestic economic crisis. However, this kind of stability rests on feet of clay while Russia’s economy remains in the doldrums. As long as retaining power is the main priority, and as long as Russian society is refused the opportunity of unimpeded evolvement and of gaining a stake in their country’s development, it is unlikely that Putin will introduce the changes necessary for an effective transformation of Russia.

About the Author

Prof. Dr. Jeronim Perović is Professor of Eastern European History at the University of Zurich and Director of the Center for Eastern European Studies (CEES). He is the author of numerous publications including “From Conquest to Deportation: The North Caucasus under Russian Rule” (2018). The present CSS Analysis was produced as part of a cooperation agreement concluded between the CSS and the CEES in January 2018.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.