After the EUGS: Specifying the Military Tasks

27 Jul 2016

By Wolfgang Wosolsobe for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 22 July 2016.

The European Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS) describes how the EU’s external action should be conducted in the coming years. It strongly emphasises the complexity of the environment and includes numerous indications on the way the military instrument(s) at the EU’s disposal should be used, further developed (in a cooperative manner) and connected to other internal and external actors. The strategy makes clear that the military has a role in external action, but always as part of a broader set of instruments.

The EUGS puts particular emphasis on the ever-closer link between military and civilian actors, essentially (though not exclusively) in the framework of CSDP, and it proposes a follow-on process whereby ‘a sectoral strategy, to be agreed by the Council, should further specify the civil-military level of ambition (LoA), tasks, requirements and capability priorities stemming from this strategy’. Even if a timeframe has not been set yet for this process, its connection to other planned processes (the Defence Action Plan, Preparatory Action, European Defence Research Programme etc.) needs to be specified. What are the possible work-strands which should flow from the EUGS?

The broad goals

A number of measures will be necessary to make the EU institutions, and particularly the EEAS, more responsive, responsible and effective in the face of a large set of new challenges. The EUGS requires member states to enhance their commitment to the EU’s external action, including their respective military contributions. It remains to be further elaborated how, in practice, the civilian and the military capability mechanisms can be harmonised – or at least coordinated – and whether they can eventually generate a common input. In fact, a modernised set of military capabilities will only have the desired effect on the EU’s external action if all the other envisaged measures are effective, too.

The following points summarise the central requirements expressed by the EUGS related to security, defence and the use of the military:

- Higher responsiveness for external action, beyond CSDP, including all military and civilian aspects;

- Qualitative change in the way member states cooperate in the military and security sectors, with a particular focus on capability development, including the ‘gradual synchronisation and mutual adaptation of national defence planning cycles’;

- Strengthening the comprehensive approach, e.g. by reinforcing civil-military command and control (C2) structures or prioritising all measures which make the security-development nexus effective in the medium and long term;

- Reinforcing the knowledge base, intelligence gathering and situational awareness;

- Further enhancing all instruments which aim at ensuring strategic autonomy in research and technology, including related aspects of cooperation.

The formulation of a LoA is just one strand of the follow-on work – yet it deserves special attention as the necessary starting point for task-related capability development.

The military tasks

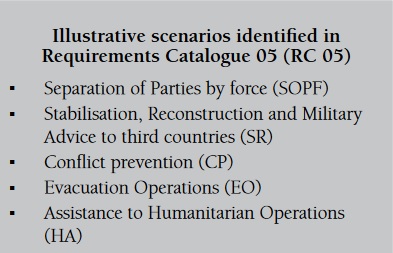

Numerous indications which may contribute to a military-specific LoA can be found across the document. A recurrent element of the EUGS is the distinction between the EU’s autonomous and cooperative action. One preliminary analytical question could be how these elements tie in with the ‘illustrative scenarios’ (IS), which are still relevant for EU military capability planning.

To start with, the EU should be able to act autonomously:

- on its territory, for security purposes: potential tasks flowing from this are not yet sufficiently defined. Broadly, this contains elements of the IS ‘HA’, but also numerous new types of tasks related to resilience, hybrid threats, terrorism and migration. There still are no indications about the concurrence and size of these tasks. The priority of follow-on analysis here would be to explore if this set of tasks requires urgent and new capability requirements;

- at its borders, to protect them: although not described in detail, this task contains a military element and is of high priority given the main strands of the externalinternal security nexus (terrorism, migration). Work which has already been initiated could be used to better integrate military and non-military instruments for this purpose;

- in its periphery, to address crises: this combines elements of the IS ‘SOPF’, ‘SR’ and ‘CP’. The current activities of CSDP (civilian and military) in the surrounding regions provide useful points of reference. Implementing the strategy requires a strong reinforcement of the EU’s presence, both in quantity and quality. The strategy repeatedly emphasises the need to ‘provide member states’ armed forces with the full set of military capabilities’. The need for a ‘full set’ (which includes special operation forces) stems from the highend options contained in the sub-tasks 1-3 below.

An important additional aspect is the required availability of EU member states military capabilities for NATO, UN and multilateral action. The EUGS describes the following tasks which can be considered as subtasks of ‘crisis-management’:

- respond rapidly, responsibly and decisively (especially to help fight terrorism): this combines aspects of rapid response with ‘SOPF’;

- provide security when peace agreements are reached and transitional governments are established or in the making: even if theoretically with a longer lead time, there still is a strong ‘rapid response’ aspect here, with ‘SOPF’ and the ability to transit towards ‘SR’;

- support and help consolidating local ceasefires […] leading to capacity building: a sub-set of the above;

- Enable legitimate institutions to rapidly deliver basic services: ‘SR’;

- Contribute to inclusive (and durable) political settlements: ‘SR’, leading back to ‘CP’.

As regards securing sea lanes, a deeper explora- tion of the desired end-state of such action and the resulting required naval capabilities is necessary, while capacity building in the periphery and fur- ther afield (with partners) most likely entails only small military engagements, closely linked to de- velopment and ‘CP’.

Moreover, the EU should participate in NATO by:

- fostering the ability of member state armed forces to contribute actively to NATO’s tasks;

- directly contributing to NATO activities;

- supporting collaborative capability building programmes.

Finally, the EU should undertake action in cooperation with NATO. The NATO-related tasks were deliberately elaborated to a lesser degree, and the EUGS strongly suggests that the ability to conduct EUautonomous tasks should take priority. Nevertheless, the recurrent references to NATO are a clear indicator that analytical work has to take into account the impact on the alliance and its member states.

About the Author

Wolfgang Wosolsobe is the former Director General of the EU Military Staff. He writes here in a personal capacity.