What British War on Terror?

31 Oct 2016

By Emily Knowles for Remote Control Project

This article external pagewas originallycall_made published by the external pageRemote Control Projectcall_made on 26 October 2016.

In evidence given to a 2016 Joint Committee on Human Rights investigation, government testimony confirmed that the UK is “not in a generalised state of conflict with ISIL, except in Iraq and Syria.” This would separate the UK position from that of the US, which declared its own global war on terror soon after the 9/11 attacks. This ushered in an era of war in Afghanistan, which has since broadened into a pursuit of “al Qaeda and its affiliates” that has driven US military actions in Yemen, Somalia, Libya, and now in Syria and Iraq against ISIS.

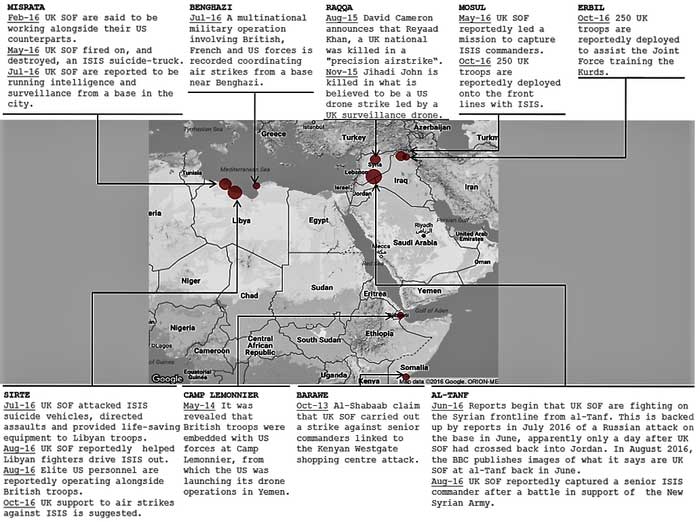

But while the UK may not consider itself a party to this global conflict, our research shows that the UK is nevertheless engaging militarily in places like Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen and Somalia alongside its American allies. Sometimes this takes place on the front lines, sometimes the UK plays a supporting role. Consistently, however, there is only a low level of public debate or institutional scrutiny. Also worryingly, the UK government has not articulated a strategy that might knit these engagements together into a coherent response to the threat of terrorism.

This briefing explores how the UK is using drones, Special Operations Forces (SOF) like the SAS, intelligence assets, and military advisers to tackle groups like ISIS, and why this allows a large number of military operations to fall through cracks in policy designed to scrutinise the use of force. Unlike when the UK deploys regular troops on the ground, the UK’s political system is poorly prepared to scrutinise this sort of remote warfare. The opacity surrounding remote warfare may be contributing to a lack of strategy, with the potential to have damaging implications for the effectiveness, accountability, and legitimacy of UK military options abroad for years to come.

Effectiveness – The fact that remote warfare is largely free from public or parliamentary scrutiny makes it far easier to authorise than the deployment of a traditional standing force. However, this runs the risk of governments choosing this form of warfare because it is expedient, rather than because it is the best possible response to insecurity. There are limited opportunities to scrutinise UK strategy, judge the success or failure of policies, evaluate the needs of military personnel, or suggest alternatives when there is little information in the public domain about what the government is currently doing, and what it is trying to achieve.

Accountability – In an age of technology, photographic evidence of UK drone strikes or SOF activity can shatter the deniability of operations in minutes. Nevertheless, the government insists on a blanket opacity policy when it comes to many forms of remote warfare, exempting its use of force outside of declared conflicts from parliamentary scrutiny. This makes it impossible to hold the government to account over its actions, even when reasonable evidence is in the public domain.

Legitimacy – Remote wars do not currently enjoy the legitimacy conferred by democratic scrutiny and public consent. In addition, without a carefully thought out, publicly stated, legal case for using lethal force outside of war zones, a recent inquiry warned that the UK’s current actions may clash with the European Convention on Human Rights, leaving the armed forces open to prosecution. Refusing to acknowledge the extent of the UK’s war on terror may therefore have ramifications for the perceived legitimacy of UK military actions, both at home and abroad.

Shining a light on the UK’s wars against terror

Mapping reports of UK military action over the last three years generates a list of countries and activities with striking similarities to those that the US has justified under its own war on terror. Far from limiting military engagement to its authorised air war against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, the UK government appears to have also signed off on military activities in places like Libya, Somalia, and Yemen, and has been able to sidestep the lack of authorisation for boots on the ground in Syria and Iraq by using SOF. Evidence suggests that there is a much larger UK war on terror underway than has been openly discussed, even if the government does not choose to think of its actions in this way.

This war is mostly carried out covertly. With exception of the UK drone strike against Reyaad Khan, the UK-assisted drone strike against Mohammed Emwazi (aka Jihadi John), the presence of UK forces in the operation room for Saudi air strikes against Yemen, and the presence of UK troops embedded in the US military at Camp Lemonnier, none of these events have been officially acknowledged or independently verified. In the cases where the UK government has responded to reports on UK SOF activity, it is only to reinstate that “the MOD’s long-held policy is not to comment on Special Forces”.

The lack of official, unclassified briefings on UK military activities forces us to rely on weak or single-sourced reports for much of the following analysis. However, whatever the individual accuracy of each report, they cumulatively stand as testament to the fact that there is a significant amount of UK military action currently being carried out under the banner of counter-terrorism without being open to discussion or scrutiny:

Libya

In February 2016, then-British Secretary of State for Defence personally authorised the use of UK bases for US air strikes against ISIS positions in Libya, despite the lack of parliamentary authorisation. In the same month, UK SOF were reported to be working alongside their counterparts in the city of Misrata, as other claims began to surface that UK SOF were escorting MI6 teams to meet officials to discuss supplying weapons and training to the regime’s army and militias.

In March 2016, the then-British Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs confirmed that ‘military advisers’, whose numbers are unknown, had been deployed to Libya, but would not comment on what they were doing. This coincided with the release of a leaked memo between Jordan and the US that revealed that UK SOF troops have been on the ground in Libya since at least the beginning of the year. In April 2016 it was stated that HMS Enterprise, a Royal Navy survey ship operating off the Libyan coast, had begun gathering intelligence on terrorist arms operations.

In May 2016, UK SOF reportedly fired on, and destroyed, an ISIS suicide-truck heading for Misrata. By July, recordings of British, French and US forces coordinating air strikes from a base near Benghazi had been released, followed by reports that UK SOF had attacked IS suicide vehicles, directed assaults and provided life-saving equipment to Libyan troops in Sirte.

This was backed up in August 2016 with reports that UK SOF had reportedly helped Libyan fighters flush ISIS out of Sirte, topped off by interviews with elite US personnel that suggested British troops are operating alongside them in the city.

In October 2016, a report suggested that the UK is supporting Coalition air strikes against ISIS in Sirte.

Somalia

In June 2007 it was reported that a joint US/UK SOF mission had been launched in Somalia to try and track down foreign terrorists. DNA samples of those killed in the raids were apparently collected and analysed, with the hope of disrupting terror cells back in the UK.

In March 2012 the former chairman of the Commons Counter Terrorism sub-Committee announced that “Somalia is clearly the site of Britain’s next overseas engagement… there have been a series of incursions into Somalia by British troops… Our Special Forces wield a considerable amount of power in the region. There is no doubt we are involved in the war against al-Shabaab.”

In October 2013, an assault took place in the coastal town of Barawe, a location linked to the leadership of al-Shabaab. Al-Shabaab claimed that British and Turkish SOF carried out the raid and that one SAS officer was killed. A Ministry of Defence spokesman said that “no UK forces at all” were involved.

In March 2016, the same leaked memo that implicated UK SOF in Libya also placed the spotlight on Somalia, with King Abdullah stating that his troops were ready with Britain and Kenya to go “over the border” to attack al-Shabaab in Somalia.

Yemen

In May 2014, it was revealed that British troops were embedded with US forces at Camp Lemonnier, from which the US was launching its drone operations in Yemen. The MoD denied that they were involved in coordinating lethal strikes, but documents released by Edward Snowdon in June 2015 suggested that a joint US, UK, and Australian programme codenamed Overhead had supported at least one lethal drone strike in Yemen in 2012.

In January 2016 the MoD admitted that British forces were present in the operation room for the Saudi air strikes against Yemen, but without having an operational role. However, a report released in April 2016 referenced interviews with Yemeni troops recounting how UK SOF have occasionally taken the lead on joint UK, US, and Yemeni operations against AQAP, indicating that the UK may well have been playing a more active role in the conflict than public statements would suggest.

The report also suggested that UK intelligence, including agents on the ground, was playing an integral part of the US strike programme – finding targets so that US drones could track their movements.

Syria

In August 2015, David Cameron announced that Reyaad Khan, a UK citizen was killed in a “precision airstrike” by a British drone over Syria, despite the fact that airstrikes were yet to be authorised. In November 2015 it was announced that the UK had provided the intelligence for a US drone strike against another UK citizen in Syria, Mohammed Emwazi (also known as Jihadi John).

In June 2016, reports began to emerge that UK SOF were fighting on the Syrian frontline from al-Tanf. A commander of the New Syrian Army confirmed in an interview that British troops crossed over from Jordan after a wave of ISIS assaults, claiming that “they helped us with logistics, like building defences to make the bunkers safe.”

This was backed up by reports in July 2016 of a Russian attack on the al-Tanf base in June, apparently only a day after UK SOF had crossed back into Jordan. In August 2016, the BBC published images of what it says are UK SOF at al-Tanf back in June, securing the perimeter.

A New Syrian Army’s spokesman refused to comment on the pictures of UK SOF, but said: “We are receiving special forces training from our British and American partners. We’re also getting weapons and equipment from the Pentagon as well as complete air support.”

In August 2016, UK SOF reportedly captured a senior ISIS commander after a battle near al-Tanf in support of the New Syrian Army. It was also reported that Royal Marines will join the SAS in training elements of the New Syrian Army in Jordan.

According to data from August 2016, it is thought that the UK has carried out some 613 aerial missions over Syria, 451 with drones and 162 with regular aircraft. UK drones released weapons over Syria 30 times, while regular aircraft released 97.

Iraq

In August 2016, reports of UK SOF on the ground began to surface despite the fact that Parliament had only authorised air strikes. Reports claimed that the UK is reportedly leading a secret mission to capture Islamic State commanders before a major assault on Mosul (May 2016), and that a UK SAS sniper had reportedly killed an ISIS suicide bomber with just one shot, in a village just north of Baghdad (Aug 2016).

In October 2016, reports suggested that some 250 UK troops have been deployed to assist the retaking of Mosul, and a further 250 have been deployed to assist the Joint Force training the Kurdish forces in Erbil.

According to data from August 2016, it is thought that the UK has carried out some 2282 aerial missions over Iraq, 976 with drones and 1306 with regular aircraft. UK drones released weapons over Iraq 418 times, while regular aircraft released 1330.

Why isn’t remote warfare scrutinised like other forms of war?

UK policy is not keeping pace with changes in the ways that wars are being waged. This has created an accountability gap that allows remote warfare to take place largely unscrutinised and with only limited coverage in the media.

1. Where the UK carries out operations with SOF rather than with regular troops, parliamentary authorisation or notification is not required. This allows them to operate in combat roles in countries where Parliament has not voted on military action, as well as in places where the relevant authorisations specifically preclude the deployment of UK troops in ground combat operations. In addition, scrutiny is severely restricted by the MOD’s long-held policy not to comment on Special Forces and the weakness of the Defence Advisory Notice System,1 which allows the government to deflect any evidence that surfaces about their use.

2. Using drones rather than conventional aircraft may allow the government to use air power without the same level of parliamentary scrutiny. In a parliamentary question in February 2016, Secretary of State for Defence Michael Fallon was asked by Labour MP David Anderson if he would guarantee MPs a debate in advance of any decision to deploy UK armed drones outside Syria and Iraq. He replied: “No.”

3. The designation of any mission as ‘combat’ or ‘non-combat’ has huge implications for its scrutiny. For example, while the then-Foreign Secretary initially stated that any military mission to Libya would trigger a parliamentary vote, Foreign Office minister Tobias Ellwood was subsequently quick to emphasise that a training mission was being considered which, because it didn’t anticipate ‘a combat role’ for UK troops, ruled a parliamentary vote out.

4. Where the UK provides capabilities to allies rather than taking an active lead in operations, it does not necessarily need to report them to Parliament. For example, in 2015 it was revealed that a small number of UK pilots embedded with the US military had carried out airstrikes in Syria against ISIS targets before parliamentary authorisation was given. In a similar vein, while UK intelligence is reportedly critical to US strikes in Yemen, the government has not had to open its activities up to scrutiny.

Mapping UK military engagement over the last three years reveals just how narrowly the government tends to define “war” when it talks about not being involved in a war on terror. While the only military actions that the government has sought parliamentary approval for are indeed restricted to air strikes against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, deficiencies in the UK’s controls on the use of force mean that the government does not necessarily need to disclose a wide range of ‘war-like’ actions if they are not carried out by regular troops. Many forms of remote warfare can be used in areas where the UK is not formally at war, without being considered official combat missions that would trigger a parliamentary vote or heightened scrutiny.

Are we winning?

Using remote warfare may feel like the only politically feasible option for governments facing strong domestic opposition to the use of military force against credible threats to national security. This does not, however, mean that it is never counter-productive.

In August 2016, a leaked White House briefing revealed that ISIS and its affiliates have spread from seven countries in 2014 when its military campaign against the group began, to thirteen countries now.

In September 2016, a briefing declassified by the US Special Operations Command (SOCOM) reported that out of the eight wars that the US has fought in since 9/11, they have tied six times and lost twice (in Iraq and Libya – interventions in Afghanistan, the Philippines, Yemen, Somalia, Uganda, and the war on ISIS in Iraq and Syria are all listed as draws).

Commentators in the US have, perhaps somewhat unkindly, termed the Obama administration’s counter-terror programmeas ‘terrorist whack-a-mole’. It is, however, true that drone strikes and air strikes, knitted together by special force deployments to assist local troops on the ground, are more suited to killing individual terrorists than defeating terrorism. It is therefore not wholly surprising that remote warfare has not yet provided an effective counter to the spread of violent extremism.

The UK’s role in this war on terror is under-reported in comparison to our American allies, and the lack of a clearly articulated strategy for interventions in places like Libya, Yemen, Somalia, Iraq, or Syria makes it hard to judge success or failure. This may well be the point. Nevertheless, the sheer scale of UK covert engagement in the war on terror means that a lack of strategy can be paralysing as well as permissive. It is therefore crucial to have a strategic review that focuses on effectiveness, to ensure that the political expediency of secrecy is not the deciding factor in how the UK conducts its military engagements abroad.

Conclusions

Involving the UK in complex conflicts is always risky, and poor decision-making and a lack of clear strategy can derail even well-intentioned contributions to peace and security. Opacity increases these risks, as it is extremely difficult to judge the success or failure of objectives that aren’t disclosed, in theatres of war the government won’t admit that the UK is party to. When the effectiveness of UK action abroad is at stake, it is particularly important to know that decisions are not being driven by political expediency rather than strategic calculation.

Remote warfare has removed regular soldiers from the battlefield, and has reduced the normal layers of scrutiny and media disclosure that usually go alongside them. The fact that the UK public, and the parliament that represents them, do not have access to much official information about the UK’s wars on terror means that there can be no meaningful, informed debate about the UK’s role in some of the most important conflicts of our age. This lack of accountability means that a shift towards remote warfare has distanced the public and the parliament that represents them from the wars being waged in the name of their security.

It is still unclear what the long-term implications of this distancing will be. However, a recent inquiry warned that the UK’s lack of a carefully thought out, and publicly stated, legal case for using lethal force outside of war zones may leave the armed forces open to prosecution. In addition, remote wars do not currently enjoy the legitimacy conferred by democratic scrutiny and public consent. Troops deserve to know that they have public backing, that they are fighting for legitimate causes, and that their actions are part of a larger strategy for peace and stability.

The extent of UK military actions abroad detailed in this briefing demonstrates how far remote warfare as a strategy has outpaced our ability to monitor, scrutinise, and improve the government’s responses to insecurity. UK policy is simply not keeping pace with changes in the way that we are engaging in conflict, which may have severe implications for the effectiveness, accountability, and legitimacy of UK military action.

Notes

1 The Defence Advisory Notice System is the non-legally-binding system that the UK Government uses to advise the media about whether publishing material they receive about SOF might be harmful to national security. In addition to SOF, the system covers information on military operations, nuclear and non-nuclear weapons and equipment, ciphers and secure communications, sensitive installations and home addresses, and UK Security and Intelligence Services. (http://www.dnotice.org.uk/danotices/index.htm)

About the Author

Emily Knowles is a project manager at the Remote Control project. Prior to joining Remote Control, Emily worked for Transparency International’s Defence and Security Programme, analyzing the links between corruption, conflict and state fragility, and working with the military and policy makers to address corruption’s impact on stability.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.