Closing Space and Fragility

27 Oct 2016

By Thomas Carothers for United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made on 4 October 2016 by the external pageFragility Study Group (FSG)call_made, which is jointly convened by the external pageCarnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP)call_made, the external pageCenter for a New American Security (CNAS)call_made and the external pageUS Institute for Peace (USIP)call_made.

The complex nature of state fragility impedes the search for effective policy responses. While a useful shorthand, state fragility spans a vast sweep of contexts, from troubling patterns of poor state functioning to complete state breakdown. Different indices of fragility produce differing lists of fragile states. The range of causal factors contributing to fragility is wide. Yet as international attention to fragility has increased in recent years, it has converged around at least one central common feature of fragile contexts – systemic exclusion – and one common prescription – encouraging inclusive governance.

Of course, exclusivity and inclusivity are themselves not simple concepts, each having its own multiplicities of meaning and interpretation. The adjective “inclusive,” for example, now appears almost everywhere in policy discussions in the development world, attached to any number of nouns as a polymorphous good – whether it is inclusive politics, inclusive governance, inclusive economics, inclusive states, or inclusive development. Moreover, inclusivity is not just about politics and economics – social and cultural inclusiveness is also relevant. For some analysts, democracy is key to achieving inclusive governing systems. For others, democracy is chronically riddled with patterns of exclusivity due to the tendency of elites to dominate democratic politics.

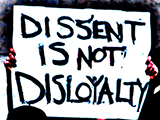

Understanding fragility through the lens of exclusion and inclusion highlights the important connection between fragility and the growing global trend of closing space for civil society. During the past 10 years, a startlingly large number of governments in developing and post-communist countries – by some measures more than 70 governments – have taken steps to curtail, sometimes drastically, independent civil society within their countries. They have done so through legal and regulatory measures restricting the ability of civic groups to organize and operate, extralegal harassment and intimidation, and political messaging that calls into question the legitimacy and authenticity of such organizations. A common element of governments’ efforts to close space for civil society is measures restricting foreign support for civil society and denunciations of such foreign support as subversive activity.

The closing space actions by some prominent countries, especially Russia and China, have attracted the most attention. Yet the phenomenon is widespread, extending to every region and to very different types of governments, not just authoritarian and semiauthoritarian ones, but to some democracies as well, such as India and Indonesia.

Governments engaged in closing space for civil society usually emphasize the foreign intervention angle – highlighting their efforts to block foreign funds from flowing to activists within the country. Doing so allows them to defend their actions at home in terms of protecting national sovereignty and to play to the nationalist bleachers. This emphasis on the foreign funding dimension inevitably pulls U.S. and other Western policymakers into arguments with these governments about what kinds of politically oriented external assistance are legitimate. Although the external support dimension of the closing space phenomenon is important, and worth fighting over, it ends up drawing attention away from the more fundamental issue at stake: the fact that some governments are trying to stop the broad empowerment of citizens made possible by economic and technological development and the resultant rebalancing of power between states and citizens.

When international attention to civil society emerged in the 1990s, as a part of the wave of democratic transitions in developing and post-communist countries, most power holders in these countries did not take civil society all that seriously. They were still attached to the traditional conception of sociopolitical life as being determined by contending political forces – above all, politicians and political parties. The mushrooming of nongovernmental organizations taking place in their countries appeared to them something of a sideshow. They were often puzzled why Western policymakers and aid providers gave so much attention to what seemed to them to be marginal groups led by marginal figures.

Yet with the passage of time, their outlook on the core dynamics shaping political life began to change. On the one hand, citizens in many transitional countries became disillusioned with and alienated from formal political life. Opposition political parties failed to build strong constituencies and were relatively tamable by power holders bent on maintaining power indefinitely in the many semiauthoritarian or dominant party systems that emerged out of once promising democratic transitions. Yet on the other hand, civil society began to demonstrate real power, including even the ability to oust deeply entrenched power holders. An unfolding series of mass assertions of civic mobilization and demand for change starting in the late 1990s and continuing across the years – in Serbia, Georgia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere – was deeply sobering to strongmen leaders and political elites all over the world. In addition, the growing ability of civic actors to generate serious pressure for specific policy changes on a whole range of social, political, and economic issues – such as the environment, anti-corruption, and women’s rights – further under-cut the idea of civil society as simply the dabbling of marginal figures. It became clear in many countries that as citizens withdraw their faith and energy from formal political institutions they are transferring them to the civic sphere.

Thus sobered, and in fact threatened, by the emerging reality of the power of independent civil society, power holders throughout the developing and post-communist worlds have been seeking to put the civil society genie back in the bottle. They attempt to paint these efforts in the colors of national sovereignty and authenticity. Yet their efforts are at root a desire to preserve an increasingly outdated idea of states as fully sovereign actors relative to citizens.

CLOSING SPACE RESPONSE: GOING BEYOND DEMOCRACY AND RIGHTS

Reflecting the fact that the United States has long been a major supporter of civil society development around the world and that U.S. public and private aid providers have been the direct target of many closing space actions, the U.S. government has been a leader in attempting to formulate a policy response to the closing space phenomenon. In 2013, President Barack Obama launched the “Stand with Civil Society” initiative, a global call to action to support, defend, and sustain civil society around the world. The administration has worked actively in many countries to partner with other concerned external actors as well as local civic activists to push back against measures to limit civil society space. Together with some other concerned governments and some private foundations, it has helped develop and fund various new mechanisms to support civil society abroad, especially embattled civic activists, such as the Lifeline: Embattled Civil Society Organizations Assistance Fund and six “Regional Civil Society Innovation Hubs.” The administration has also raised the issue of freedom for civil society at the United Nations and other multilateral forums and sought to advance international norms protecting rights of civic activists.

The U.S. government’s response to the closing space challenge has been serious. Yet U.S. policy-makers have not adequately drawn the connection of closing space to the issue of state fragility. They usually frame the issue in terms of its implications for democracy and human rights, not through the broader developmental lens of inclusivity and, by extension, state fragility. Thus they base policy responses to closing space on the general U.S. interest in promoting democracy and rights abroad. Yet given that significant parts of the mainstream U.S. foreign policy community view support for democracy and human rights as a specialized values issue, one that is peripheral to or even in tension with core U.S. security interests, this view of the closing space challenge tends to put it in the category of optional issues – to be pursued only to the extent other, more pressing “hard” interests allow.

Yet the connection between closing space and fragility is powerful and direct. When a government closes off space for independent civil society, it is creating a significant structural obstacle to achieving inclusive governance and positive state-society relations. An active, diverse civil society is the key to empowering marginalized groups, creating multiple channels for citizen participation, mediating diverse interests in a peaceful fashion, and in general creating state-society relations based on mutual communication, respect, and consensus. When a government shuts down space for civil society it is not just damaging the U.S. interest in democracy and human rights, it is undercutting the U.S. interest in reducing political exclusivity in developing countries, a principal driver of state fragility. Thus, the closing space phenomenon directly connects to all of the profound negative security challenges arising from the negative effects of fragility playing out in so many countries in the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and elsewhere.

IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. POLICY

The consequences for fragility of closing space actions are telling. Two important examples in this regard are Egypt and Uzbekistan.

Stunned by the massive outbreak of citizen mobilization and activism of 2011, core parts of the Egyptian power establishment soon began pushing back hard against the independent civic sector. In 2011, the Egyptian government launched a high-profile prosecution of U.S. and other providers of support to Egyptian civic groups. It used the issue of alleged foreign interventionism as an entry point for what became a broad, systematic campaign to undercut independent civil society in Egypt. This has been an extremely harsh process, consisting of crosscutting punitive legal and regulatory actions aimed at imprisoning, silencing, or driving into exile prominent civic activists, and closing down the most assertive and independent groups.

The result of this campaign should not be understood simply in terms of the abridgment of basic political and civil rights in Egypt, serious though that is. It has been a process of societal exclusion, undercutting basic elements of inclusivity that had begun to develop in the late 2000s and appeared to flourish in 2011. It is a rejection of active, open state-citizen relations, a rejection that decreases state responsiveness, increases state brittleness, and worsens the problems of political fragmentation and radicalization. In other words, the closing of civil society space is laying the groundwork for significant potential state fragility in Egypt.

Many debates in the U.S. policy community over how the U.S. government should react to the Egyptian government’s campaign against civil society are cast in terms of democracy and rights: Should the U.S. interest in democracy and rights in Egypt outweigh the value of maintaining positive relations on security and economic issues with the Egyptian government? Yet seeing the closing space problem through the fragility lens alters the terms of the debate. The policy question becomes: Should the United States overlook actions by the Egyptian government that are paving a path toward serious state fragility for the sake of near-term security and economic concerns? Given the devastating consequences of state fragility elsewhere in the region and how they would be multiplied by serious fragility in Egypt, the answer clearly is no.

Uzbekistan presents similar issues. In the early 2000s, the Uzbek state began striking hard at the country’s fledgling independent civil society. As in Egypt, the government emphasized Western support for local civil society organizations as a primary danger. The campaign was much broader than that, aiming to reverse the modest but significant development of independent organizations in the country that had taken place during the 1990s. The result of the campaign has been near-total asphyxiation of the independent sector and the forceful reassertion of state-society relations based on the supremacy of the state and the complete submission of society.

As with Egypt, these negative developments are often discussed in Western policy circles primarily as a loss for democracy and rights, which of course they are. Yet in closing down civil society, the Uzbek state has struck hard against inclusiveness in politics, economics, and other domains, leading to worrying signs of growing societal fragmentation around religion. Hardline exclusion of Islamist actors appears to be contributing to radicalization of some Islamists and an increased tendency on their part to engage in violence against the state. The potential long-term consequences for the country and for regional security are worrying.

In short, a map of where the closing space phenomenon is taking place in the world is not just a map of troubling alerts for global democracy; it is also a guide to where conditions that foster state fragility are being put into place in many countries. Understanding the closing space problem as being directly linked to the broader policy challenge of addressing state fragility has several major implications for the U.S. policy community.

First, the calculus for closing space policy should not be seen as values versus hard interests, but rather values plus hard interests on one side versus whatever other interests may be on the side of accepting the asphyxiation of civil society. When U.S. policymakers weigh the inevitable trade-offs in their engagements with fragile states, they should treat closing space not just as a setback for democracy and human rights but as an accelerant on fragility and instability, with all the implications that holds.

Second, U.S. responses to closing space for civil society should not be the sole purview of that part of the interagency process that focuses on democracy and human rights issues. It should also be the concern of those parts of the defense, diplomacy, and development communities that are working together to reduce state fragility. This wider engagement will mean a broader range of potential tools for exerting pressure against governments moving backward on civil society space, including incentives relating to economic aid and military cooperation.

Third, the next administration has no alternative but to sustain, and indeed elevate, American leadership on this issue. The “Stand with Civil Society” initiative – the umbrella for the administration’s current responses on the closing space issue – is closely identified with Obama himself, given his strong personal role in it. As a result, it may be tempting for the next U.S. president to discontinue or downgrade this initiative, given the general tendency in U.S. foreign policy of incoming presidents not to take up initiatives that are seen as personal enthusiasms of their immediate predecessors. Yet if the closing space issue is understood as being connected to the security concerns associated with state fragility, the need for continuing and in fact broadening the U.S. response to it becomes clear. Mounting an effective policy response to state fragility is not an issue that will be optional for the next U.S. president.

Fourth, given that the United States has been out ahead of most other Western governments in identifying the seriousness of the closing space problem and formulating a policy response to it, Washington should work actively within the overall community of policy actors engaged on state fragility to highlight the connection between closing space and fragility and incorporate concerns over closing space actions into their broader efforts on combating fragility. This will mean expanding the efforts to insert closing space concerns into multilateral forums and mechanisms beyond those primarily relating to democracy and rights (such as the Community of Democracies and the Open Government Partnership) to others with a broader development remit, such as the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States.

As U.S. policymakers have learned the hard way over the years, all good things often do not, unfortunately, go together. But bad things quite frequently do. The troubling, even alarming trend of closing space for civil society around the world has a direct but not always recognized link to the large problem of state fragility. Recognizing and acting on this connection can be a way for the United States and other Western policymakers to broaden and fortify their response to the closing space problem, while adding an important dimension to their diagnosis and tackling of state fragility.

About the Author

Thomas Carothers is vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He directs the Democracy and Rule of Law Program and oversees several other Carnegie programs, including Carnegie Europe in Brussels, the Energy and Climate Program, and the D.C.-based Europe Program.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.