Brexit and European Insecurity

20 Nov 2017

By Daniel Keohane for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published in Strategic Trends 2017 by the Center for Security Studies on 22 March 2017.

The British exit from the EU is feeding into a general sense of uncertainty about the EU’s future. This uncertainty may be further exacerbated by US President Donald Trump, who has called into question both NATO’s and the EU’s viability. But irrespective of Brexit or the Trump administration’s actions, it is vital that France, Germany, and the UK continue to work closely together on European defense post-Brexit.

The British exit from the EU – “Brexit” – is occurring while European governments face an unprecedented confluence of security crises. These range from an unpredictable Russia to conflicts across the Middle East, which are generating internal security tests such as terrorist attacks and refugee flows. The US is ambiguous about putting out all of Europe’s fires and expects allies to take on more of the military burden. And no European country can cope alone.

More broadly, Brexit is feeding into a growing sense of European insecurity. The new US president, Donald Trump, supports Brexit and seems nonplussed about the future of the EU, adding succor to nationalist movements across the Union. Elections during 2017 in the Netherlands, France, Germany, and perhaps Italy, all founding EU member-states, may produce strong results for Brexit-loving politicians – such as Marine Le Pen in France – that further question the viability of the EU project. At the very least, Trump’s outlook could further complicate already-difficult Brexit negotiations between the UK and its EU partners.

In addition to EU uncertainty, Brexit is causing a distinct sense of self-doubt for the UK, too. Two of the four parts of the United Kingdom voted to remain in the EU in the June 2016 referendum: Northern Ireland and Scotland. Depending on the economic consequences of the UK’s Brexit deal with the EU, instability could easily return to Northern Ireland, while Scotland (where UK nuclear weapons are currently located) may hold another independence referendum. Both Unions – the EU and the UK – have reasons to feel insecure because of Brexit.

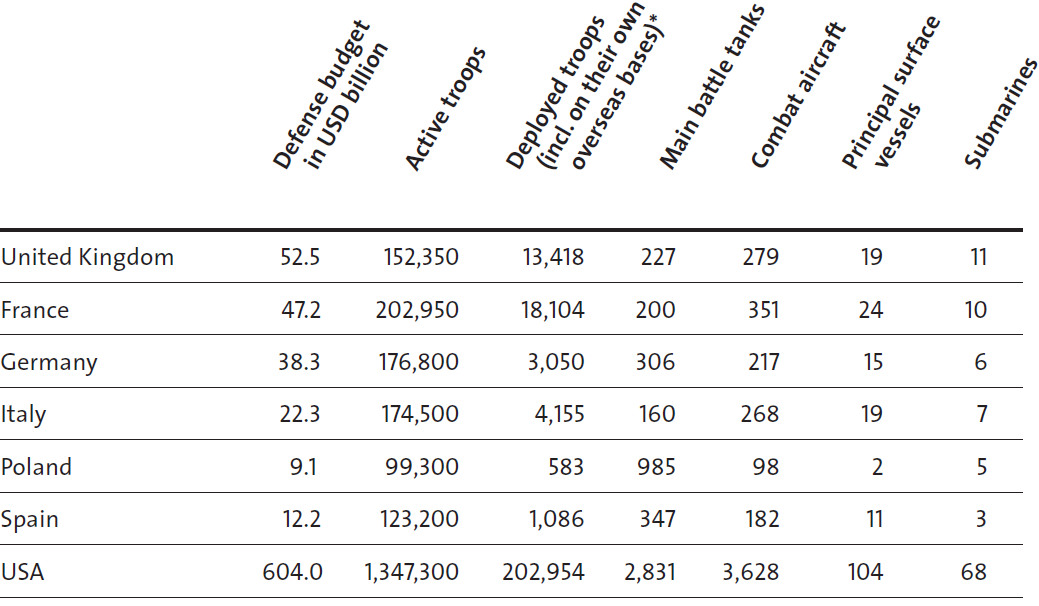

More specifically, that Brexit will reduce the potential usefulness of EU security and defense policies should be self-evident, since the UK is the largest European military spender in NATO. Those who believe that because the UK remains a nuclear-armed member of NATO, nothing much should change for European defense had better think again. Brexit might hinder European military cooperation because it could greatly strain political relationships with other European allies, especially with the next two leading military powers in NATO-Europe: France and Germany. But if handled constructively, military collaboration could become one of the most fruitful areas for cooperation between the UK and the EU post-Brexit.

With regard to NATO’s future, the election of Donald Trump as US president has an even greater potential to transform Europe’s strategic landscape than Brexit if he scales back the US military commitment to European security. But irrespective of what Trump thinks in theory and what his administration does in practice, European defense post-Brexit will require much closer trilateral political and military cooperation between France, Germany, and the UK.

The Brexit Effect on EU Military Cooperation and NATO

Following the UK vote to leave the EU in June 2016, the remaining 27 Union governments have committed themselves to improving the performance of EU security and defense policies. Although it is not fair to blame the UK alone for the EU’s prior lack of progress on defense, cheerleaders for a common defense policy in Berlin, Paris and elsewhere have seized on the Brexit vote as an opportunity to strengthen that policy area. In large part based on a number of subsequent practical Franco-German proposals, EU foreign and defense ministers approved new plans for EU security and defense policies in mid-November.

Since the Brexit vote, German Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen had at times accused the UK of paralyzing progress on EU defense in the past, and asked it not to veto new plans. In turn, British Defense Secretary Michael Fallon has occasionally suggested that London would veto anything that smacked of an “EU army” or undermined NATO (such as an EU version of NATO’s military headquarters, SHAPE).1 Thankfully, this divisive rhetoric died down towards the end of 2016, as it has become clear that EU security and defense plans will not undermine NATO and that the UK will not use its veto.

With the approval of the UK (which retains its veto until it departs the Union), EU heads of governments approved a package of three plans covering aspects of capability development, operational planning, and military research, among other issues, at a European Council summit on 15 December 2016. However, despite their good intentions, the proposals are unlikely to have much immediate impact, and whether or not the remaining 27 EU governments will collectively deliver more on defense remains an open question.2

For instance, while Berlin and Paris agree on much, there are some major differences in their respective strategic cultures. For one, France, as a nuclear-armed permanent member of the UN Security Council, has a special sense of responsibility for global security, and is prepared to act unilaterally if necessary. Germany, in contrast, will only act in coalition with others, and remains much more reluctant than France to deploy robust military force abroad.

For another, Berlin and Paris do not necessarily agree on the end goal of EU defense policy. Calls in the 2016 German defense white paper for a “European Security and Defense Union” in the long-term give the impression that EU defense is primarily a political integration project for some in Berlin.

The French are more interested in a stronger inter-governmental EU defense policy today than a symbolic integration project for the future, since Paris perceives acting militarily through the EU as an important option for those crises in and around Europe in which the US does not want to intervene. Because of their different strategic cultures, therefore, France and Germany may struggle to develop a substantially more active EU defense policy than their joint proposals would suggest.3

Moreover, the French do not assume that their EU partners will always rush to support their military operations. In general, they haven’t robustly supported France in Africa in recent years, although Germany has enhanced its presence in Mali since the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks. But if acting through the EU could help ensure more military support from other EU members, France would find that preferable to acting alone. The trouble for France has been its awkward position between a Germany reluctant to use robust military force abroad and a UK reluctant to act militarily through the EU.

Post-Brexit, French strategic culture will remain closest to that of the British. The EU could only develop a defense policy because France and the UK agreed that it should, at St. Malo in 1998. Moreover, London and Paris have been prepared to act together, leading the charge for what became NATO’s intervention in Libya in early 2011. To reinforce the European part of NATO, the ongoing quiet deepening of bilateral Franco-British military cooperation, based on the 2010 Lancaster House treaties, is vitally important.

For example, London and Paris conducted a joint military exercise with over 5,000 troops in April 2016, as part of their broader ongoing effort to develop a combined expeditionary force, and in November 2016 they announced that they would deepen their dependence on each other for missile technology. Indeed, Franco-British cooperation is much more militarily significant for European security than the recent developments trumpeted by the EU, which have produced little of concrete military value so far. Furthermore, Anglo-French military collaboration could become even more important if President Trump were to scale back the US military commitment to European security.

But bilateral Franco-British military cooperation may not be immune to politics. And it is important to try to avoid a spillover effect from the Brexit decision onto NATO, especially any political rift between Europe’s two leading military powers, the traditionally more “Europeanist” France and more “Atlanticist” UK. Even before Trump’s election in November 2016, in a speech on 5 September, British Defense Secretary Fallon said: “Given the overlap in NATO and EU membership, it’s surely in all our interests to ensure the EU doesn’t duplicate existing structures. […] Our Trans-Atlantic alliance works for the UK and for Europe, making us stronger and better able to meet the threats and challenges of the future”.4

In contrast, on 6 October 2016, French president Hollande said: “There are European countries which believe that the USA will always be there to protect them […] We must therefore tell these European countries […] that if they do not defend themselves, they will no longer be defended […] the USA is no longer in the same mindset of protection and defense.” Hollande added that “Europeans must be aware […] they must also be a political power with defense capabilities”.5

If these Franco-British positions were to harden – because of difficult Brexit negotiations – and cause a political rift, it could hinder not only their bilateral cooperation, but also cooperation through (and between) both NATO and the EU. Strong Franco- British cooperation is vital for European security, not only because of their combined military power, but also because Europeans need to be able both to contribute more to NATO (as the UK prioritizes) and to act autonomously if necessary (as France advocates, via the EU, or in other ways).6

However, President Trump’s admiration of Brexit and declaration that it wouldn’t worry him if the EU broke up could not only exacerbate Franco- British divisions during difficult Brexit negotiations, but could also encourage a broader divide within NATO (of which more below) between an Anglo-sphere and a Euro-sphere. That is in nobody’s interest except that of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who wishes to destabilize the Atlantic alliance. It is no wonder that other EU governments are worried about the future of European security, not only the effect of Brexit on the EU and NATO.

The European Army Alphabet Soup

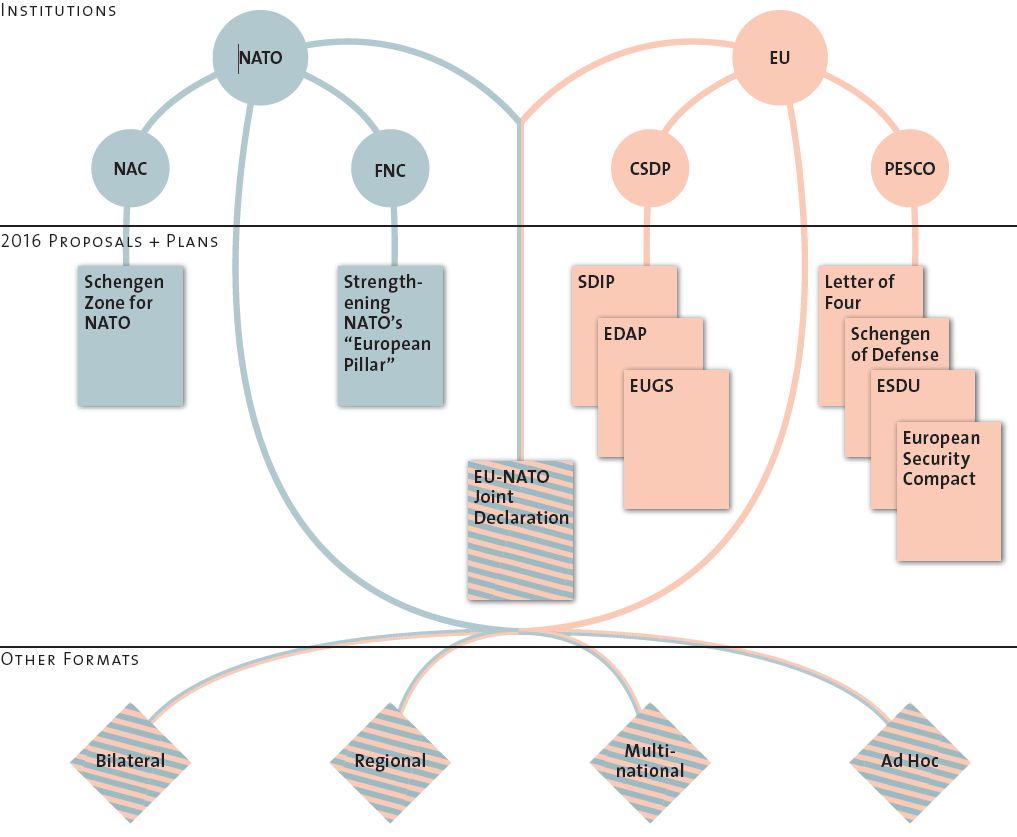

Institutions

NAC North Atlantic Council: Brings together all of NATO’s 28 members, decisions are taken by inter-governmental consensus

FNC Framework Nations Concept: Forms part of broader idea to strengthen the “European Pillar” of NATO, e.g. by pooling and sharing military capabilities

CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy: Inter-govern-mental framework for military cooperation housed within EU foreign policy structures, part of broader international security policies

PESCO Permanent Structured Cooperation: A legal mechanism to allow a smaller group of EU countries cooperate more closely together on military matters, may be triggered during

2017 2016 Proposals + Plans

Schengen Zone for NATO: Freedom of movement for soldiers and military equipment across NATO internal borders, an idea supported by US Army Europe & others

Strengthening NATO’s “European Pillar”: Europeans to take on more of NATO’s military burdens, such as meeting NATO’s 2% of GDP spending goal – highlighted in July German White Paper

EU-NATO Joint Declaration: A cooperation program agreed at the July NATO Warsaw summit, 40+ proposals in 7 areas such as migration, cyber, hybrid threats, exercises etc.

EUGS EU Global Strategy: A document published in June outlining the objectives of EU foreign and security policies, drafted by EU HR/VP Mogherini

EDAP European Defense Action Plan: December Proposals to augment financing of military research and joint equipment programs, and opening up national defense markets, presented by the European Commission

SDIP Security and Defense Implementation Plan: Follow-on document to EUGS focusing on security and defense aspects approved in December, drafted by EU HR/VP Mogherini

European Security Compact: A June Franco-German call to beef up the EU’s contribution to international security and improve EU’s ability to tackle internal security threats

ESDU European Security and Defense Union: A long-term goal to create a common defense for the EU, proposed in July German White Paper

Schengen of Defense: An August Italian proposal for a permanent multinational European force outside institutional structures but available to EU/NATO/UN.

Letter of Four: An October Franco-German-Italian-Spanish call for exploring the use of the PESCO mechanism in the EU treaties

Other Formats

Bilateral: Examples include Franco-British, German-Dutch

Regional: Examples include Nordic, Benelux, Visegrad

Multinational: Examples include the European Air Transport Command, Eurocorps

Ad Hoc: Examples include military operations like current one against Daesh

Military Cooperation Between the UK and the EU Post-Brexit

The UK government should hope that EU governments do deliver on their defense promises, including after the British exit from the EU. There are three reasons for this. First, some EU operations are useful for coping with the vast array of security challenges facing Europe at large. NATO cannot – and the US does not want to – be everywhere. This largely explains why most EU military operations have taken place in the broad geographic space (beyond EU territory) stretching from the Western Balkans via the Mediterranean and Africa to the Indian Ocean, to counter pirates, terrorists, and people smugglers, among other tasks. This emerging strategic necessity helps explain why the British defense secretary has said that after its departure, the UK could still contribute to EU operations.7

Second, Europeans need to improve their military capabilities and spend their sparse defense monies more effectively. The EU institutions in Brussels can help the governments with funding for defense research, by opening up protected national military procurement markets, and by providing financial incentives for more efficient multinational equipment programs. All of this would benefit taxpayers and soldiers alike, as well as NATO, since 21 countries will remain members of both the EU and NATO post-Brexit.

Third, the EU and NATO are deepening their practical cooperation, and European security can only benefit from these two organizations working together. To tackle terrorism or the refugee crisis, between them the EU and NATO can connect everything from internal policing and intelligence networks to external military operations. Both bodies are conducting operations to combat people-smuggling across the Mediterranean, for example. To counter Russian hybrid belligerence, they are also trying to improve the coordination of their various efforts, from economic sanctions to territorial defense, cyber-defense, and countering propaganda.

This is why NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has welcomed the (mainly) Franco–German proposals for strengthening EU security and defense policies. At a September 2016 informal meeting of EU defense ministers in Bratislava, Stoltenberg highlighted that there is no contradiction between better EU military cooperation and a strong NATO, noting that they are mutually reinforcing.8

Because of these three reasons – alongside Britain’s substantial military capacity, intelligence assets, and operational experience – it is in everyone’s interest to have as close a relationship as possible between the UK and the EU on military matters after Brexit. The UK, for example, may wish to continue contributing to useful EU operations. Non-EU European members of NATO, such as Norway and Turkey, have made significant contributions to some EU operations in the past.

More broadly, it would make sense for the EU and UK to continue to align their positions on common international challenges, such as sanctioning Russia, and to work as closely together as possible. Malcolm Rifkind, the former UK foreign secretary, has suggested that: “What we will need, in future, is a EU+1 forum whenever the countries of Europe are seeking to promote a common foreign policy to ensure that global policy is not the monopoly of the US, China and Russia with Europe excluded.”9

An EU+1 forum might work on an ad-hoc basis for specific challenges. But in general, the UK cannot realistically expect a formal say over EU foreign or defense policies in return for alignment with EU foreign policy positions or contributions to EU operations. British diplomats would probably prefer a permanent observer status on EU foreign policy decision-making committees to an ad-hoc, issue-by-issue approach, which implies “take it or leave it” choices for the UK. But a permanent observer status for the UK would prove difficult.

It is true that pre-accession countries, such as the ten governments that joined the EU in 2004, were able to enjoy observer status on some inter-governmental EU foreign policy-making formats. But the UK is not trying to join the EU, it is leaving. Plus, other non-EU European members of NATO who will not join the EU for the foreseeable future, particularly Norway and Turkey, would likely expect similar arrangements. At the same time, the remaining 27 EU governments are keen to protect their decision-making autonomy.

Instead, London should aim for de-facto rather than de-jure influence post-Brexit. Beyond ad-hoc observer status on standing inter-governmental EU decision-making committees, this could also involve selective inclusion of the UK in some issue-specific ad-hoc decision-making formats – such as steering boards – based on London’s willingness to participate in a particular capability project or contribute to a military operation at hand. For example, if the UK is willing to make a significant contribution to an EU military operation, while some EU members may not wish to participate, ways should be explored to ensure a formal say for London in how that operation is run.10

These types of ad-hoc arrangements would require a lot of political trust between the UK and the remaining 27 governments. But given the UK’s deep knowledge of EU procedures and challenges – alongside its global outlook, strong military capabilities, operational experience, and vast international networks and knowledge – it is likely that London would have considerable de-facto influence on other EU governments if it chose to. Handled constructively, defense policy could become one of the most fruitful areas for cooperation between the UK and the EU after Brexit.

As long as it remains an EU member, therefore, there is not much point in London threatening to veto any future agreements on EU military cooperation, as they would almost certainly happen anyway after the UK has left the EU. It would also needlessly antagonize France, Germany, and others when the UK has much more important things to negotiate with its EU partners. The British government should instead wish its EU partners well in their endeavors to make EU military cooperation more effective, safe in the knowledge that the UK can no longer be blamed for any future lack of progress on EU defense policy.

Brexit Negotiations and the Trump Card

Post-Brexit, European military cooperation will continue to be pushed more by the convergence of national priorities than by the efforts of the EU and NATO. European military cooperation is mainly bottom-up – driven by national governments – not top-down, meaning directed and organized by the institutions in Brussels. European governments are increasingly picking and choosing which forms of military cooperation they wish to pursue, depending on the capability project, or military operation at hand. Sometimes they act through NATO or the EU, but almost all European governments are using other formats as well, whether regional, bilateral, or ad-hoc coalitions.11

Other EU governments will continue to want to work with the UK in bilateral or other settings, as well as at NATO, just as the UK should work with them. British Prime Minister Theresa May has constructively emphasized that regardless of Brexit, the UK will remain strongly committed to European security: “Britain’s unique intelligence capabilities will continue to help keep people in Europe safe from terrorism […] Britain’s servicemen and women, based in European countries including Estonia, Poland, and Romania, will continue to do their duty. We are leaving the European Union, but we are not leaving Europe.”12

Policy-makers in London are well aware that other EU governments will want to continue working closely with the UK on security matters, to the extent that some see it as strengthening the UK’s Brexit negotiating position. Malcolm Chalmers from the Royal United Services Institute has described the situation thus: “As concern over the future terms of a Brexit deal grows, some of those involved in shaping policy have been tempted by the argument that the UK should use its ‘security surplus’ – its role as the leading Western military and intelligence power – as a bargaining chip that could be ‘traded’ in return for commercial concessions in the post-Brexit settlement with the EU.”13

Chalmers cautions against taking such a path, linking UK security guarantees to economic interests such as access to the EU’s single market, since it could undermine the mutual confidence on which those security guarantees depend. Charles Grant of the Center for European Reform suggests that this approach has already gone down badly in some Central and Eastern EU members: “[The UK] recently sent about 1,000 troops to Estonia and Poland. Given this contribution to European security, some government advisers have suggested, EU member-states – and especially those in Central Europe – should go the extra mile to give the UK a generous exit settlement. However […] Some Baltic and Polish politicians who heard it last summer were miffed, saying they had thought the UK was sending troops because it cared about their security; but now it appeared to be a cynical move to ensure better terms on a trade deal.”14

Moreover, although the UK is the largest European military spender in NATO, its ability to contribute as much as it would wish to European security may be hampered by the ongoing impact of Brexit on the British economy and the UK government budget. The hope is that the impact of Brexit on UK military spending and capability will not be as debilitating as the fallout from the economic crisis of 2008 onwards. The 2010 UK defense review led to the reduction of the UK army to its lowest manpower numbers since the Napoleonic era, and a number of key capability projects were scrapped or delayed (such as aircraft carriers).15

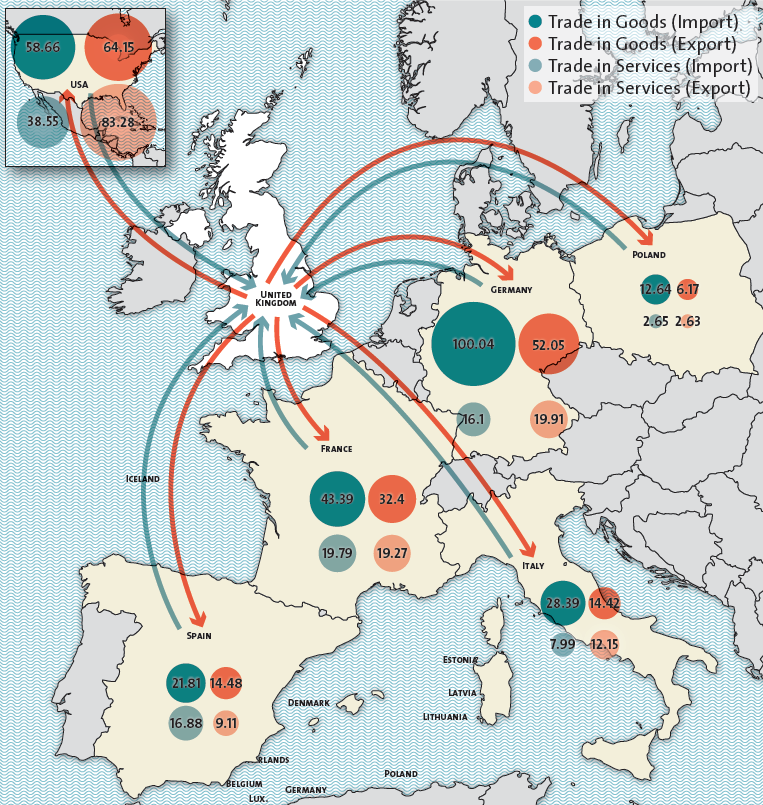

The United Kingdom’s Trade Relations with Selected Countries

As of 2014, in billion USD

However, Brexit is already biting into the British defense budget to some degree, mainly due the fall in the value of the pound sterling: A January 2017 report from the UK National Audit Office said that the projected costs of funding the UK’s current defense equipment plan, which takes Britain from 2016 to 2026, had risen by 7 per cent during 2016, compared with a rise of 1.2 per cent between 2013 and 2015. This will require British defense officials to find nearly £6 billion of additional savings from their equipment plan in ten years if they are to remain within budget.16

In addition, some in London now expect that the US will reinforce the UK’s position in its forthcoming Brexit negotiations. President Trump has declared his admiration of Brexit, and stated that it wouldn’t worry him if the EU broke up. In a joint interview before his inauguration with the British Times and German Bild (conducted with Michael Gove, a leading pro-Brexit UK politician), Trump said that not only would Brexit “end up being a great thing”, but also that the EU would continue to break apart. Trump explained: “People, countries, want their own identity and the UK wanted its own identity.”17

Some pro-Brexit politicians in the UK interpret Trump’s November electoral victory (and outlook) as additional justification for the British exit from the EU. The world is changing, so the argument runs, and the UK will emerge as a pioneer in the new sovereigntist world order, not least because of a re-booted “special relationship” with the US. Following a meeting with Trump on 9 January 2017, British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson said that the then US president-elect had “a very exciting agenda of change”, and that the UK was “first in line” for a free trade deal with the US after the Trump administration took office (technically, however, this cannot happen for at least two years, since the UK cannot formally agree a bilateral trade deal with the US or any other non-EU country until after it has left the EU).

Johnson elaborated further at the Munich Security Conference in February 2017, referring to Brexit as “liberation” from the EU.18 But the UK’s embrace of Trump, combined with the US president’s nonchalance towards the EU’s future, could divide NATO allies, with the US and the UK on one side and France, Germany, Italy, and Spain on the other. Similar to the bitter splits over the 2003 Iraq war, this could potentially force other European governments to choose sides. In that scenario, everyone would lose out.

Alternatively, in a more optimistic scenario, the UK could potentially act as a bridge between Europe and the new US administration on reinforcing NATO, which could play positively into the ongoing Brexit negotiations with EU partners. UK Prime Minister Theresa May did manage during her January visit to Washington to get a public agreement from the new US president that he backs NATO “100 per cent”. But most other Europeans are less convinced by Trump’s words on NATO, they await his actions. Moreover, in stark contrast to Boris Johnson’s views, the chairman of the Munich Security Conference, Wolfgang Ischinger, summed up how many in the remaining EU-27 countries feel about Trump’s views on the EU, calling them a form of “war without weapons”.19

As Charles Grant from the Center for European Reform has put it: “A related card cited by British officials is Donald Trump. His questionable commitment to European security, and the increasingly dangerous nature of the world, could make partnership with Britain more valuable to continental governments. But the Trump card could easily end up hurting the British. The more that British ministers cozy up to Trump, and avoid criticizing his worst excesses, the more alien the British appear to other Europeans, and the more the UK’s soft power erodes.”20

New Deals on European Defense?

Trump’s views on NATO are more mixed than his views on the EU, if not altogether re-assuring to most Europeans: “I said a long time ago that NATO had problems. Number one it was obsolete […] Number two the countries aren’t paying what they’re supposed to pay […] which I think is very unfair to the United States. With that being said, NATO is very important to me.”21

The problem with Trump’s general approach to world affairs is that it favors creating an international bazaar of bilateral deals, centered on what the president thinks is best for the US, over working with more stable global and regional institutions.22 That the US created the current global system of institutions and rules – for very good reasons – seems to be neither here nor there for Trump. No wonder that many in Brussels and elsewhere worry for the future of both NATO and the EU.

Much commentary has focused on the key role Germany will have to play to keep the EU together following the UK’s Brexit vote during the Trump era. The departing UK aside, some other major EU countries may not be so resistant to the US president’s ideas. The current conservative government in Warsaw shares much of Trump’s nationalist worldview. Following his election, Polish Prime Minister Beata Szydło said: “A certain era in world politics ends […] Democracy won despite the liberal propaganda.”23

Warsaw has been fighting with the EU institutions in Brussels over the rule of law in Poland, and meets the NATO target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defense. Sounds like Trump’s kind of European ally, a country he might want to tempt to leave the EU with a bilateral trade deal. Moreover, if Trump continues to be dissatisfied with NATO as a whole, might Poland be tempted to try to cash in and strike a bilateral deal with the US on defense?

Alternatively, if Trump and Putin were to agree a new geopolitical arrangement over the heads of NATO allies, a kind of updated Yalta conference, would that push Poland towards better bilateral relationships with Germany, France, the UK, and others? In some respects, this has already been happening. Since 2015, Germany has placed a battalion of mechanized infantry under the command of a Polish brigade. In November 2016, Poland and the UK announced their ambition to agree on a bilateral defense treaty.

As Poland’s potential choices suggest, deeper bilateralism across Europe may be the best way to resist the temptations and turbulences of Trump. Malcolm Chalmers of the Royal United Services Institute has suggested such a course for the UK: “The election of Trump as US president could also lead to further pressure on European states, including the UK, to take a greater share of responsibility for their own security. Given this, the UK is likely to want to further deepen existing efforts to improve bilateral defense cooperation with European NATO members (for example, France).”24

To reinforce the European part of NATO, the ongoing quiet deepening of bilateral military cooperation between Europe’s two leading military powers, France and the UK, based on the 2010 Lancaster House treaties, is vitally important. Germany is also working on a roadmap for military cooperation with the UK to ensure that tight cooperation on military matters survives Britain’s exit from the EU.25 Preserving the EU, and developing more effective EU military cooperation (as outlined above), will depend to a large degree on stronger Franco-German cooperation – although the Berlin-Paris engine is in dire need of a kick-start.

However, deeper bilateralism between the major European powers may not be enough to strengthen Europe’s defenses. No European member of NATO wants to lose the protection of the US. But Europeans would be wise to at least collectively improve their own defenses, in case they can no longer depend on NATO – meaning the US – as much as before. Moreover, Europeans – in particular the French, the Germans, and the British – should probably also consider whether they would be able to defend themselves collectively if they had to, a question that has been, until now, a taboo in European defense discussions.

Selected Military Capabilities

As of 2016

Currently, the main state-based military threat to European security is Russia. Although it is possible that Moscow might risk a shooting war with a European NATO member, that is far from obvious, and Russia may prefer to wage war via hybrid means. In 2016, France, Germany, and the UK combined spent USD 138 billion on defense, whereas Russia spent USD 58.9 billion.26 But Russia is not the only threat to European security. There is a wide range of security challenges across the EU’s broad neighborhood that may require Europeans to use military means without US help, such as preventing conflicts or helping weak states like Mali fight terrorists.

The elephant in the room for such a European defense plan would be nuclear deterrence.27 If Trump were to withdraw the US nuclear umbrella – which should be very unlikely – would France and the UK be willing and able to provide nuclear-armed protection for other Europeans?28

In any case, deeper European cooperation in the defense of Europe could not be credibly carried out via the EU, since the UK will depart, and some EU countries (such as Austria, Ireland, and Finland) are not yet willing to join a military alliance. The EU, unlike NATO, is not an inter-governmental military alliance (let alone moving towards creating a federal European army under the political control of Brussels-based EU institutions), and is far from capable of defending its territory from attacks by external states like Russia.29

Depending on the precise nature of any US military scale-back, something like a strengthened European pillar of NATO would probably be required.30 In the worst case, perhaps even a revived Western European Union – a now-defunct military alliance of ten European governments that preceded EU defense policy, separate from the EU and NATO –, might be needed. 31

In particular, deeper European cooperation for defending Europe will require much closer political and military alignment between Berlin, Paris, and London. One misfortune of Brexit is that it is occurring just when British, French, and German defense policies have been showing some signs of convergence in recent years. Each country is aiming – to varying degrees – to be able to meet as broad a spectrum of tasks as possible, maintain the ability to defend their territories, and also deploy abroad.

Each of them has promised to increase defense spending in the coming years, reflecting the difficult security crises that Europe faces today. All three have made important contributions to NATO’s reassurance measures to allies in Eastern Europe, such as participating in Baltic air policing. Moreover, all three have deployed forces to help fight Islamist terrorists in Africa and the Middle East.

It is true that Germany has been reluctant to take on full-blown combat roles abroad. But its beefed-up support for the coalition against the so-called “Islamic State”, following the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, alongside its willingness to lead one of NATO’s four new battalions in Eastern Europe, suggests that Germany realizes that it needs to be prepared to contribute more militarily to European security.32

France has sometimes been suspected of being too Russia-friendly, but it cancelled the delivery of two Mistral amphibious assault ships to Moscow after the 2014 annexation of Crimea. Britain has long been accused of being anti-EU military cooperation. But the EU’s most successful military mission to date, an anti-piracy operation in the waters off Somalia, has been run from a British military headquarters.

In essence, European military cooperation – whether through the EU, NATO, or other formats – is a tale of three cities, because it can fully work only if Berlin, London, and Paris agree. Encouragingly, in November 2016 a joint meeting of French, British, and German defense chiefs took place in Paris. Regardless of what the Trump administration in the US does, the minimum challenge now for France, Germany, and the UK will be to ensure that the British exit from the EU will not make political alignments on European defense more difficult to achieve.

Notes

1 Daniel Keohane, “external pageAn EU HQ? Let them at itcall_made”, in: Royal United Services Institute, 11.10.2016.

2 Sophia Besch, “external pageEU Defense, Brexit and Trump: The Good, the Bad and the Uglycall_made”, in: Center for European Reform 14.12.2016.

3 Daniel Keohane, “external pagePolicy or Project? France, Germany, and EU defensecall_made” in: Carnegie Europe, 02.08.2016.

4 UK Ministry of Defense, external pageDefense Secretary speaks at Université d’étécall_made, Paris, 05.09.2016.

5 François Hollande, external pageFrance’s European Visioncall_made, Jacques Delors Institute, 06.10.2016.

6 Daniel Keohane, “external pageNATO, the EU, and the curse of Suezcall_made”, in: Carnegie Europe, 14.10.2016.

7 Ben Farmer / Kate McCann, “external pageBritain 'can still join EU military missions after Brexit'call_made” in: Daily Telegraph, 20.07.2016.

8 NATO, external pageNATO Secretary General welcomes discussion on strengthening European defensecall_made, 27.09.2016.

9 Malcom Rifkind, “external pageNeither ‘hard’ nor ‘soft’: how a smart Brexit should lookcall_made”, in: European Leadership Network, 18.10.2016.

10 Nicole Koenig, “external pageEU External Action and Brexit: Relaunch and Reconnectcall_made”, in: Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin, 22.11.2016.

11 Daniel Keohane, “The Renationalization of European Defense Cooperation”, in: Oliver Thränert / Martin Zapfe (eds.), Strategic Trends 2016 (Zurich: Center for Security Studies, 2016), 9-28.

12 UK Prime Minister’s Office, external pageThe government's negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speechcall_made, Lancaster House London, 17.01.2017.

13 Malcolm Chalmers, “external pageUK Foreign and Security Policy after Brexitcall_made”, in: Royal United Services Institute, 01.2017.

14 Charles Grant, “external pageMrs May’s emerging deal on Brexit: not just hard, but also difficultcall_made”, in: Center for European Reform, 20.02.2017.

15 Daniel Keohane, “Is Britain back? The 2015 UK Defense Review”, in: CSS Analyses in Security Policy, No. 185 (2016).

16 UK National Audit Office, external pageMinistry of Defense: The Equipment Plan 2016 to 2026call_made, 27.01.2017.

17 external pageFull transcript of interview with Donald Trumpcall_made, in: The Times, 16.01.2017.

18 Philip Stephens, “external pageBoris Johnson forgets the messagecall_made”, in: Financial Times, 21.02.2017.

19 Patrick Donahue, “external pageGermany’s Former U.S. Envoy Warns of ‘War Without Weapons’ Between Trump, EUcall_made”, in: Bloomberg, 13.02.2017.

20 Charles Grant, “external pageMrs May’s emerging deal on Brexit: not just hard, but also difficultcall_made”, in: Center for European Reform 20.02.2017.

21 external pageFull transcript of interview with Donald Trumpcall_made, in: The Times, 16.01.2017.

22 Thomas Wright, “external pageTrump’s 19th Century Foreign Policycall_made”, in: Politico, 20.01.2016.

23 Rick Lyman, “external pageEnthusiasm for Trump in Poland Is Tempered by Distrust of Putincall_made”, in: New York Times, 19.11. 2016.

24 Malcolm Chalmers, “external pageUK Foreign and Security Policy after Brexitcall_made”, in: Royal United Services Institute, 01.2017.

25 Patrick Donahue / Matthew Miller, “external pageGermany Forging Post-Brexit Defense 'Road Map' With the UKcall_made”, in: Bloomberg, 19.02.2017.

26 International Institute for Strategic Studies, external pageThe Military Balancecall_made (2017).

27 Daniel Keohane, “external pageMake Europe Defend Again?call_made”, in: Carnegie Europe, 18.11.2016.

28 Oliver Thränert, “No Shortcut to a European Deterrent”, in: CSS Policy Perspective Vol.5/2 (2017).

29 Daniel Keohane, “external pageSamuel Beckett’s European Armycall_made”, in: Carnegie Europe, 16.12.2016.

30 Jean-Marie Guéhenno, “external pageWhy NATO needs a European pillarcall_made”, in: Politico, 11.02.2017.

31 Ann Applebaum, “external pageEurope needs a new defense pact – and Britain can lead itcall_made”, in: Financial Times, 15.02.2017.

32 Daniel Keohane, “Constrained Leadership: Germany’s New Defense Policy”, in: CSS Analyses in Security Policy No. 201 (2016).

About the Author

Daniel Keohane is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zürich. His CSS publications include “The Renationalization of European Defense Cooperation” (2016), and “Is Britain Back? The 2015 UK Defense Review” (2016).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.