No 99, Caucasus Analytical Digest: Georgia´s Relations With the EU

10 Nov 2017

By Shota Kakabadze, Tinatin Zurabishvili and Shu Uchida for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Caucasus Analytical Digest on 30 October 2017.

The Choice to Be Made: Georgia’s Foreign Policy after the Association Agreement

By Shota Kakabadze (University of Tartu)

Abstract

As a result of the parliamentary elections of October 2016, a political party with a clear anti-NATO and anti-EU political platform made it to the parliament. The Alliance of Patriots was not able to win any majoritarian districts but still managed to receive enough votes to pass the 5% threshold in the country-wide proportional vote. This contribution looks at foreign policy discourses in post-election Georgia and argues that a possible explanation for the rise of such populist parties can be found in the ambiguous messages coming from the West. To be more precise, as the EU’s Eastern Partnership does not offer a membership perspective, it becomes harder for the political elite to sell the pro-European foreign policy agenda to the Georgian public. The issue of the two breakaway territories remains unresolved, Russia maintains a military presence there, while for the foreseeable future NATO and the EU membership is off the table for Georgia. Hence, in such circumstances, unless substantial progress in relations with the Euro-Atlantic institutions is made, the message of the Alliance of Patriots—that pro-Western foreign policy endangers Georgia, leaving it to face the Kremlin alone—could gain more support.

Introduction

In the summer of 2017, Georgia was fighting forest fires all around the country. The strongest of these forest fires was in Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park, a place that had already suffered from the same fate during the Russian–Georgian War in 2008. It took a couple of days and support from Azerbaijan, Turkey, Armenia and Belarus to extinguish the forest fire. As is usually the case with Georgian politics, this natural disaster quickly led to political arguments and mutual accusations. Social media plunged into the conspiracy theories, some pointing fingers at the Kremlin, calling the forest fires sabotage and even an “undeclared war” (Kuntchulia 2017). In addition, discussion concerning the possibilities and options of foreign help to fight the fire illustrated the role of Russia in the domestic discourse of the political parties.

News broke that, allegedly, Georgian authorities had asked for help from their Russian counterparts. This move was heavily criticized by the main opposition parties, describing such an act as treason. “Asking the occupants for help” and “same people who started the fire in 2008” became the key reference points around which criticism aimed at the ruling party was mounted. On the other hand, the Alliance of Patriots, the only publicly anti-Western party in the parliament, welcomed such possibility and even encouraged the government to do so. As the leader of the party claimed, none of the European states would have rejected the offer of help coming from Russia (Tabula 2017). Meanwhile, Ada Marshania, an MP from the party, went as far as to argue that such cooperation would have created a good basis for neighbourly contacts. In response to the criticism that Russia was responsible for the fire in 2008, she claimed that the Kremlin may have regretted its behaviour (on.ge 2017). The ruling party tried to distance itself by claiming that there was indeed such an offer, but it was initiated on the Russian side. In addition, the prime minister of Georgia said that Georgia would have considered such an option, as the country would welcome any help, but there was simply no need (on.ge 2017b).

To trace the truth as to whether it was the Russian authorities who expressed their desire to help or the other way around is not the aim of this analysis. What is relevant for the argument put forward here is the ambiguity and debates surrounding the possible cooperation with Russia, Georgia’s large neighbor to the north. The key argument is that even though the Kremlin continues to maintain a large military presence and full control over the two breakaway Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the taboo against cooperating with Russia on the political and diplomatic level seems to be softening in the public discourse. A possible explanation for this softening taboo can be found in the ambiguous messages about Georgia’s Western perspective coming from the Russia.

The key reference point for this paper concerns the results of the parliamentary elections of 2016 and the political agenda brought to the table by the newly formed Alliance of Patriots, which challenges the dominant discourse on Georgia’s pro-Western orientation from its stage in the parliament. It is argued below that as the signing of the Association Agreement (AA) and visa liberalisation with the EU has been achieved, the integration process must be taken to a whole new level, the most obvious form of which would be an EU membership perspective for Georgia. Otherwise, with the feeling that Georgia has reached the end of its Euro-Atlantic path, political messages similar to those the Alliance of Patriots is projecting become more relevant and popular. The message that NATO would never accept Georgia as a member, while such aspirations expose Georgia to dangers from Russia, is gaining public visibility. This can be observed by the increased activities of pro-Kremlin NGOs and political parties over the last years. In 2013, the Eurasian Institute founded the Public Movement for Georgian–Russian Dialogue and Cooperation (GeoRus.org 2017), in April 2015, a news agency with its own TV channel—Tbilisi 24 was established, it carries clear anti-Western and pro-Russian messages etc. This contribution argues that the results of the parliamentary elections of 2016, which allowed the Alliance of Patriots to get into parliament, should be interpreted in this context.

Parliamentary Elections of 2016

The result of the parliamentary elections of 2016 was the first major signal to the possible challenge of the state’s foreign policy agenda. While Georgian Dream (GD) and United National Movement (UNM) received most of the seats, the major liberal, pro-Western parties were excluded. Parties such as Republicans or Free Democrats were not able to secure seats in the legislative body. Interestingly, the former chairwoman of the parliament, Nino Burjanadze, whose party is famous for its clear pro-Russian stand, also did not manage to receive enough votes to cross the threshold. Such developments can be explained by the general distrust towards political parties in Georgia, which rose from 22% in 2012 to 41% in 2015, while trust went down from 21% to 8% in the same period (Caucasus Barometer 2017a). In this context the newly formed populist Alliance of Patriots, with its xenophobic and homophobic campaign as well as support for a dialogue with the Kremlin, offered an alternative to the older political establishment and received just slightly above 5 percent and thus qualified for the minimum of 6 seats.

It must be noted that the Alliance, unlike Burjanadze’s party, was rather careful in promoting its foreign policy agenda. The starting point of its political platform was not the clear rejection of the EU or NATO but rather the idea that the membership perspective for either organization does not exist; hence, it is important for Georgia to start approaching Russia and thinking about restoring diplomatic relations with its Northern neighbour. Party discourse could be described as similar to the right-wing populist parties on the rise across the continent. The head of the party, Irma Inashvili, is quoted as saying, “The contemporary world nowadays is throwing away what I call pseudo liberalism and pseudo liberal values. It got tired, it threw it away and is moving to something different and new, and what are these new different things? In reality, it is going back to the past” (Inashvili in Clash of Narratives 2017a). In an interview for the same miniseries about the political landscape in Georgia, she also made an interesting statement that illustrates the key idea of the party’s foreign policy platform: “I was 21 when I visited Brussels for the first time and the door to NATO was opening, and we had high hopes. But today I am 46 years old, NATO is still telling us that the door is open but also telling us gently that it will not accept us” (Inashvili in Clash of Narratives 2017b).

From this perspective, one can see the greatest vulnerability for the current official foreign policy agenda on which the Alliance of Patriots can build its Western-sceptic platform. This could also explain the idea of a Georgia–NATO–Russia format, which was proposed by the party. Coming back from its visit to Moscow, the Alliance claimed that it was received with interest by the Russian side (Tabula 2017b). The Alliance of Patriots went as far as holding manifestation in the centre of Tbilisi and announcing a hunger strike demanding the realization of the Georgia–NATO–Russia project (Tabula 2017c). It must be noted that the special representative of NATO in the region has commented in response that the organization is not going to negotiate over Georgia with any third party (on.ge 2017c).

The ruling party, in addition to distancing itself from the oppositional MPs’ visit to Moscow, describing it as a private event, firmly continues to be in line with what one might call the dominant discourse. To be more precise, whenever the discussion of possible meetings between the heads of Russian and Georgian states arises, Georgian officials are quite clear that there can be no meeting unless the main topic to be discussed is the de-occupation of the two Georgian breakaway regions. This ultimatum itself leads to an impasse in which there seems to be no way out unless one of the sides compromises on its core principles. Restoring an official diplomatic relationship would require Georgia to accept what Russian diplomats have many times called “new realities”, i.e., the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Without such a move, reopening the Russian embassy to Georgia is extremely complicated both from a legal and political perspective.

It is important to emphasize that the existing impasse does not automatically guarantee that the dominant pro-Western discourse will survive and reproduce itself unless further progress is made towards integrating into the Euro-Atlantic institutions. If the Association Agreement and the visa-free regime of the European Union, as well as the current NATO–Georgia package, represent the end of the journey, thus not offering a clear membership perspective, the niche for nationalistic and relatively anti-Western political discourse will grow. Moreover, parties such as the Alliance of Patriots will be able to fill this gap and further challenge the foreign policy agenda. The existence of a European perspective has a considerable impact on the domestic political agenda as well. The Association Agreement with the EU became a key driving force and justification for reforms, which sometimes come across as painful and difficult. The anti-discrimination bill which was adopted in 2011 is just one example. It was one of the requirements Georgian authorities had to deliver as part of the Visa Liberalisation Action Plan.

As of July 2017, the parliaments of the Eastern Partnership countries that signed the Association Agreement (i.e., Moldova, Georgia and Ukraine) have issued a mutual declaration calling on the European Parliament to consider the membership perspective, citing Article 49 of the treaty of the European Union. In a way, a parallel can be drawn with the process of integrating into NATO, and it echoes what the speaker of the parliament of Georgia at that time, David Usuapashvili, remarked in 2014, prior to the NATO summit in Wales. He claimed that “this magical word MAP [Membership Action Plan]” had become for Georgians symbolic of the answer to the question as to whether “the free world needs Georgia”, or “does the free world keep its promise that Georgia would become a NATO member?” (Usupashvili, as cited in Liklikadze 2014). In addition, within the same speech delivered in Tallinn, he argued that an answer of “no” would undermine political stability in Georgia. “One option is to take up arms and fight against the occupant country, which we do not want. The second is to become a member of free Europe and step by step achieve success. A third option is going back to a modernized Soviet Union or Russian empire. No other options exist. Hence, it will be hard to sell to the people the non-existence of progress or very small progress towards integration into NATO...It does not work anymore” (ibid).

To illustrate this point further, one could look at how the perception of the European Union and North Atlantic Treaty Organization among the Georgian population has changed over time. Whereas in 2009 and 2011 the combined share of those who thought of the relationship with the European Union as rather good or very good amounted to over 40%, in 2013 and 2015 this number fell below 30%. 2017 saw a slight boost in the positive attitudes towards the EU with rather good and very good making up together about 35%. (Knowledge of and attitudes toward the EU in Georgia, 2009–2017) This can be explained by the Association Agreement and visa-free regime with the European Union, which created the impression that the pro-Western foreign policy was making progress. To illustrate this point further, another survey showed that in 2011 support for membership of the European Union stood at 69% in Georgia, while in 2015 it went down to 42%. Interestingly, the share of those who oppose EU membership tripled from 5% to about 16% over the same period (Caucasus Barometer 2017b). The same applies to support for NATO membership, which dropped from 70% in 2010 to 37% in 2015, while the share of those who are not in favour rose from 8% to 20%. (Caucasus Barometer 2017c).

The way the outcome of the Wales summit was branded and presented to the wider public should be understood in this context. NATO member states agreed that instead of a membership action plan, they would propose the substantial NATO–Georgia package (SNGP), which also implied the establishment of a joint training and evaluation centre. NATO Secretary General at that time, Anders Rasmussen, claimed that the package would prepare Georgia for membership (Civil.ge 2014), but somehow an actual membership perspective is always postponed. Looking back at late President Eduard Shevardnadze’s promise made in 1999—that by the year 2005, Georgia would be knocking on NATO’s door—today, it seems that the door is open; there is no need to knock anymore, but entry is still not possible.

Conclusion

To conclude what has been argued above, after signing the Association Agreement and achieving a visa-free regime with the European Union, the current pro-Western foreign policy discourse needs a further boost. A membership perspective or a related clear message from the West towards Georgia could serve as one. If this does not happen, Georgia will see an increase in Euro-sceptic sentiments and a rise in political entities serving them. Their influence will become even stronger if the Association Agreement with the EU is in fact the final destination of Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic journey rather than just one of the stops on the road.

References [all accessed 27 September 2017]

- Clash of Narratives: A Tale of Two Georgias | Episode One: Freedom vs Tradition 2017-a, Coda Story [video file]Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pHQ5Y6ex08&list=PL0w0DC8uARXy1_4sV1cGokwSNrffgVKal> [Clash of Narratives: A Tale of Two Georgias | Episode Three: Winners and Losers 2017-b, Coda Story [video file] Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmWdyezZAIU&index=3&list=PL0w0DC8uARXy1_4sV1cGokwSNrffgVKal>

- Caucasus Barometer time-series dataset Georgia, Trust – Political Parties (2017-a) Caucasus Research Resource Centre [online] Available at: http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/TRUPPS/

- Caucasus Barometer time-series dataset Georgia, Support of Georgia’s Membership in the EU (2017-b) Caucasus Research Resource Centre [online] Available at http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/EUSUPP/

- Caucasus Barometer time-series dataset Georgia, Support of Georgia’s Membership in NATO (2017-c) Caucasus Research Resource Centre [online] Available at: http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/NATOSUPP/

- Knowledge of and attitudes toward the EU in Georgia (2009–2017) Caucasus Research Resource Centre [online]Available at: http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/datasets

- აპატურაი: NATO, მის და საქართველოს ურთიერთობაზე, რუსეთთან მოლაპარაკებას არ აპირებს (Appathurai: NATO is not going to discuss its relations with Georgia with Russia) On.ge 13 July 2017-c [online] Available at:< http://go.on.ge/eld>

- ინაშვილი: რუსეთის დახმარებაზე უარს არცერთი ევროპული ქვეყანა არ ამბობს • ტაბულა. (Inashvili: no European country refuses help from Russia) Tabula 23 August 2017-a [online] Available at: http://www.tabula.ge/ge/story/123357-inashvili-rusetis-daxmarebaze-uars-arcerti-evropuli-qvekana-ar-ambobs

- ინაშვილი: უნდა დავიწყოთ პოლიტიკური პროექტის რეალიზაცია - საქართველო-ნატო-რუსეთი (Inashvili: we should start realization of the project Georgia–NATO–Russia) Tabula 17 September 2017-c [online] Available at: http://tbl.ge/2iaj

- კვირიკაშვილი რუსეთისგან დახმარების შემოთავაზებაზე: ასეთი წინადადება მისასალმებელია (Kvirikashvili on the help offer from Russia: such offer is welcomed) On.ge 24 August 2017-b [online] Available at: http://go.on.ge/g02

- კუნჭულია ლ. (2017). გახშირებული ხანძრები: ვინ და რატომ უწყობს გამოცდას საქართველოს?. (Kunchulia, L. increased fires: who and why tests Georgia?) Radio Liberty. [online] Available at: https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/khandzrebi-grdzeldeba/28715692.html

- ლიკლიკაძე, კ. (2017) ხელისუფლების MAP-ის პოლიტიკა (Liklikadze, K. Government’s MAP policy) Radio Liberty [online] Available at: https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/khelisuplebis-mapis-politika/25234612.html

- მარშანია რუსეთზე: ეგება და ნანობს თავის საქციელს, მიეცი საშუალება, რომ ჩააქროს ხანძარი(Marshania on Russia: maybe she regrets its behaviour, give her chance to put out the fire) On.ge 23 August 2017-a [online] Available at: http://go.on.ge/fzh

- მარშანია: რუსეთს საქართველო-NATO-რუსეთის ფორმატის შექმნა შევთავაზეთ (Marshania: we offered Russia to create Georgia–NATO–Russia format) Tabula 13 July 2017-b [online] Available at: http://tbl.ge/2ep4

- რასმუსენი: არსებითი პაკეტი საქართველოს ნატოს წევრობისთვის მოამზადებს (Rasmussen: substantial package will prepare Georgia for NATO membership) Civil.ge 05 September 2014 [online] Available at: http://www.civil.ge/geo/article.php?id=28658

- სახალხო მოძრაობა ქართულ-რუსული დიალოგისა და თანამშრომლობისათვის (The Public Movement for Georgian–Russian Dialogue and Cooperation) Project of the Eurasian Institute. GeoRus.org 05 July 2013[online] Available at: http://www.georus.org/index.php?do=static&page=geo-projeqt

About the Author

Shota Kakabadze is a PhD candidate and junior research fellow at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies, Faculty

of Social Sciences, University of Tartu, Estonia.

The EU as a “Threat” to Georgian Traditions: Who Is Afraid, and Why?

By Tinatin Zurabishvili (CRRC-Georgia)

Abstract

This contribution gives an overview of Georgian public opinion towards the EU based on a survey conducted in May 2017. The analysis focuses on the perceived relation between Georgian traditional values and closer integration with the EU by looking at the characteristics of those people who report the perception that the EU threatens Georgian traditions.

Introduction

EU–Georgia relations are developing at an impressive pace with the EU–Georgia Association Agreement (AA) fully entered into force on July 1, 2016. The creation of a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), a part of the AA, will eventually result in the removal of many customs tariffs and trade quotas between the two parties and will facilitate Georgia’s gradual integration into the EU single market. The number of Georgian laws harmonised with EU legislation is regularly growing. Importantly, visa liberalisation entered into force on March 28, 2017, allowing Georgian citizens’ short visa free visits to the Schengen zone countries.

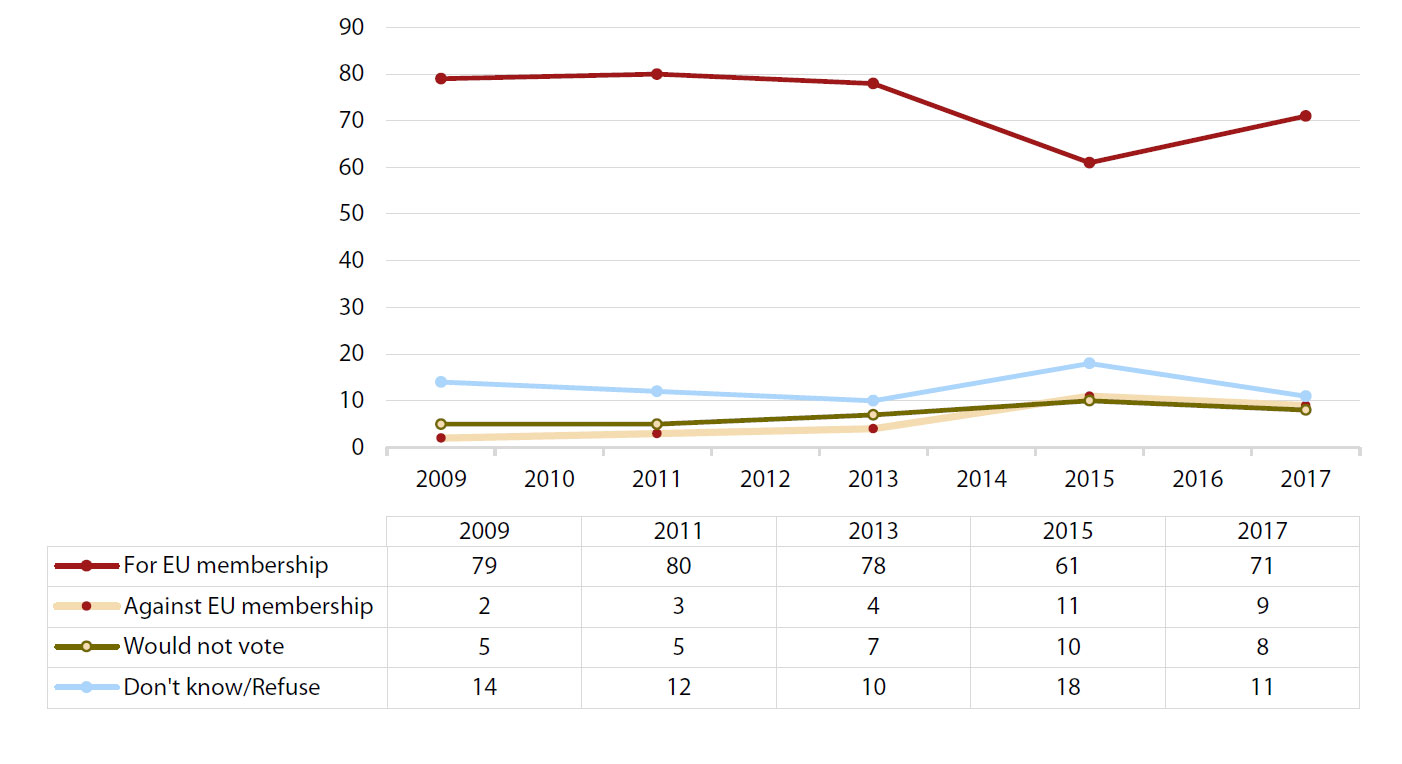

Support for EU membership enjoys consistent and strong support from the population of Georgia and has been an important factor contributing to the deepening of the relationship between the parties. Seventy-one percent of the population of the country reported in 2017 that they would vote for Georgia’s EU membership if there were a referendum tomorrow; just 1/10th of the population stated they would vote against EU membership. According to the findings of the Europe Foundation’s regular surveys on Knowledge of and Attitudes towards the European Union in Georgia, the lowest support for Georgia’s EU membership was recorded in 2015, at 61% (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: If There Were a Referendum Tomorrow Regarding Georgia’s Membership in the European Union, Would You Vote for or Against It? (%)

As the Europe Foundation’s 2015 survey report claimed, “[t]he fear that the EU will harm Georgian culture and traditions has intensified among Georgian society, which seems to largely contribute to the decrease in the number of supporters of Georgia’s EU membership.” (p. 19) This article is primarily focused on the 2017 survey data and looks at the characteristics of those people who report the perception that the EU threatens Georgian traditions.

The 2017 survey on Knowledge of and Attitudes towards the European Union in Georgia was conducted between May 9 and 31 as part of Europe Foundation’s European integration programme. In total, 2,258 respondents were interviewed countrywide. The survey findings are representative of the adult population of Georgia except for people living in the occupied territories and on military bases. Weighted results are presented in this article.

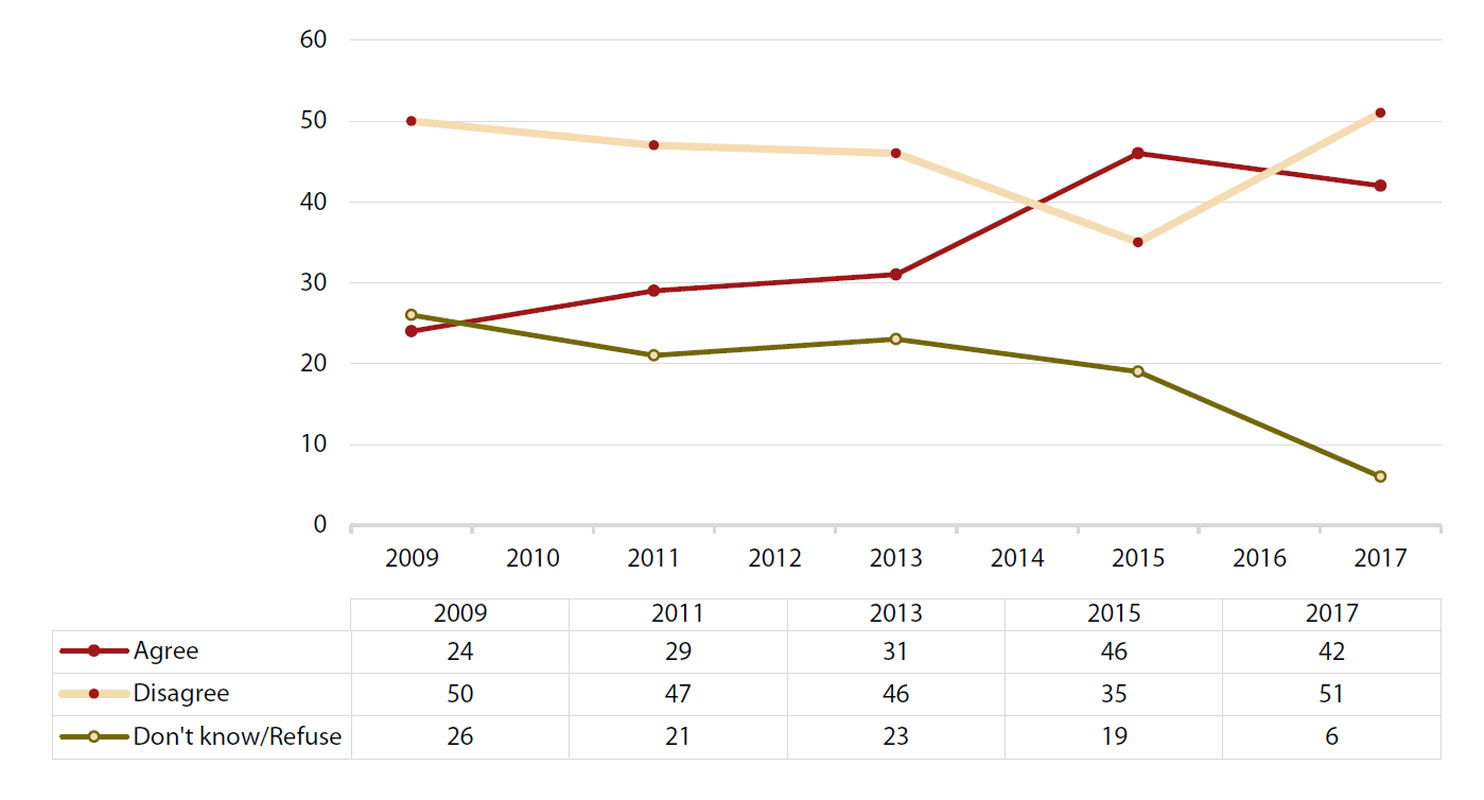

While overall assessments of the EU and its role in Georgia have remained rather positive over time, between 2009 and 2015 the share of the ethnic Georgian population who agreed with the statement “The EU threatens Georgian traditions” doubled and, for the first time in these surveys, in 2015, the share of those who agreed with this statement exceeded the share of those who disagreed (see Figure 2). The increased perception that the EU threatens Georgian traditions coincides with decreased support for Georgia’s EU membership.

Figure 2: To What Extent Do You Agree or Disagree With the Statement: “The EU Threatens Georgian Traditions”? (%)

Who Sees the EU as Threatening Georgian Traditions?

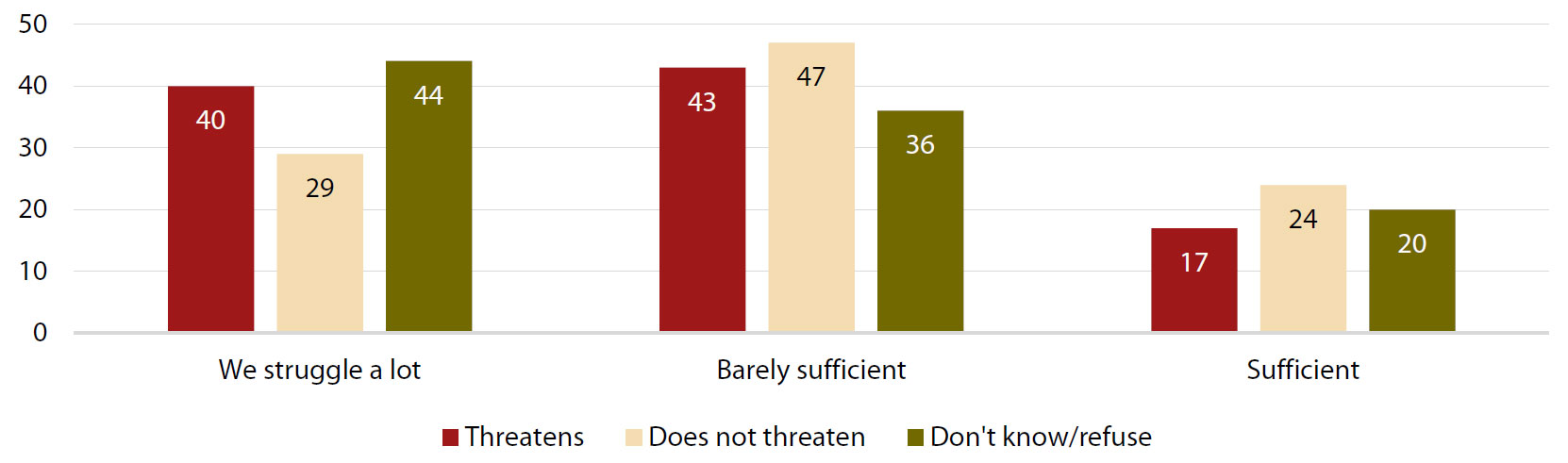

Quite surprisingly, there does not appear to be a specific demographic “profile” of people who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions. Although small differences can be seen in some basic demographic characteristics between those who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions and the rest of Georgians, the former group cannot be strongly marked as predominantly male or female, urban or rural, old or young or middle aged, religious or not, or more or less educated. Most surprisingly, the perception of the EU as a threat to Georgian traditions differs only slightly for people from households of different self-assessed well-being (see Figure 3 overleaf). For the rest of the article, only the answers of ethnic Georgians have been analysed in order to get as focused an understanding of the issue as possible. In the 2017 survey, those who identified themselves as ethnic Georgians constituted 87% of those interviewed.

While the frequency of internet usage (as well as internet access as such) is, normally, a highly characteristic “marker” of various attitudes in Georgia, this, again, is not the case in regard to the perception of the EU threatening Georgian traditions since the frequency of agreement with this statement is very similar in the groups reporting regular, occasional or no internet usage.

With about half of ethnic Georgians believing that the EU threatens Georgian traditions, one would expect some variation by major demographic characteristics. However, this is not the case, which suggests that factors other than demography determine such a belief. This belief—or, rather, this fear—is rather evenly spread throughout various “visible” groups in the society. While there is no direct answer to the question who are those who see the EU as threatening Georgian traditions, there are a number of “invisible” factors that this fear is associated with.

Figure 3: “To What Extent Do You Agree or Disagree With the Statement: ‘The EU Threatens Georgian Traditions’” By “How Sufficient Is Your Current Household Income?” (%; Ethnic Georgians Only)

Driven by Suspicion?

People who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions also tend to believe more strongly than others that it is Russia who can currently best support Georgia—not the EU and not the US. They tend to think that Russian, not the English language, should be mandatory in the public schools of Georgia. They also tend to support a Russian “orientation” for the foreign policy of Georgia and would also tend to support Georgia’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). Importantly though, support for Georgia’s membership in the Russia-led Eurasian Union still is not dominant in this group; equal shares of Georgians who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions report that they would vote for and against Georgia’s EEU membership if a referendum were held tomorrow. Concurrently, a 65% majority would vote for Georgia’s membership in the European Union. Thus, it would be a mistake to believe the Georgians in this group are strongly pro-Russian. They are, however, more pro-Russian than those Georgians who do not see the EU as a threat to Georgian traditions.

On the other hand, Georgians who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions are more critical of democratic developments in Georgia and of Georgia’s readiness for EU membership compared to Georgians who do not think that the EU threatens Georgian traditions. Considering the level of protection of human rights in Georgia, the rule of law, the formation of democratic institutions or the competitiveness of the market economy in the country, those who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions are less convinced that Georgia is ready to join the EU.

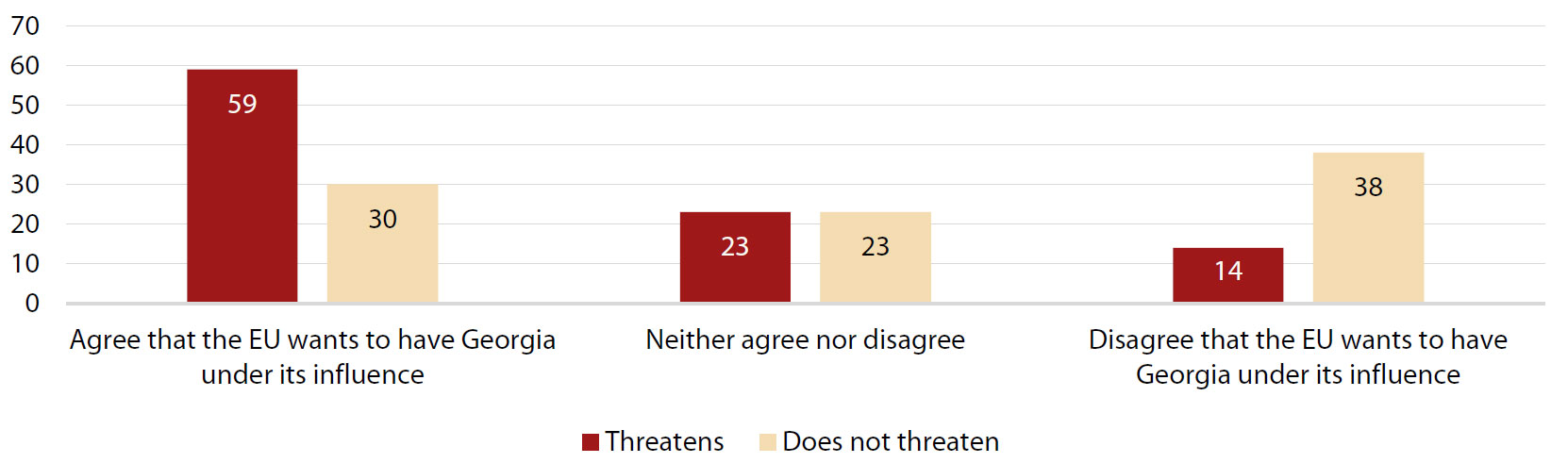

They are, further, certainly very suspicious of the EU’s intentions. They more strongly believe—in fact, twice as strongly compared to the rest of Georgians—that the EU is helping Georgia because it wants to have Georgia under its influence (Figure 4 overleaf). They also report lower trust of the EU compared to those who disagree with the opinion that the EU threatens Georgian traditions (respectively, 31% and 58%).

Georgians who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions are slightly more nationalistic than those who do not believe so. Still, they cannot be characterised as authoritarian, as they, by an impressive majority and at the same rate as the rest of the population, give preference to human rights as a supreme value, clearly placing them above state interests while answering a respective question.

Conclusion

Thus, while Georgians who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions cannot be distinguished by any particular demographic characteristic, their rather specific “profile” can be described based on the positions and preferences they report: they are suspicious of the EU’s intentions for Georgia, they are more pro-Russian than the rest of the population, and they are slightly more nationalistic. Their position on these issues is not, however, very firm and is often surprisingly inconsistent:

• While suspecting that the EU helps Georgia for far from altruistic reasons, the absolute majority (80%) still considers EU aid to be important for Georgia;

• The share of those who report trusting the EU is nearly twice as big than the share of those who report trusting the parliament of Georgia (respectively, 31% and 18%);

• 2/3 of those believing that the EU threatens Georgian traditions would still vote for Georgia’s membership in the EU if the referendum were held tomorrow;

• At a rate similar to the rest of the population, they say they would like to move to live in a foreign country—often naming EU countries (Germany, Italy) as their preferred destination.

While perfect consistency is rarely characteristic of public opinion, such conspicuous discrepancies are not common either. These inconsistencies may suggest that the positions and preferences reported by Georgians who believe that the EU threatens Georgian traditions are not deeply internalised. Whether they will, at some point, become so, is a question that can only be answered with time. More important questions though are the ones for which no empirical data are yet available: what, specifically, do people mean when they speak of “Georgian traditions”? Do “Georgian traditions” have the same meaning for all people, or do different people mean different things when speaking about traditions? What exactly do people think is being threatened, and how do they think it is being “threatened” by the EU in Georgia? Hopefully, further research will be able to answer these questions.

Figure 4: “To What Extent Do You Agree or Disagree With the Statement: ‘The EU Threatens Georgian Traditions’” By “The EU Wants To Have Georgia Under Its Influence” (%; Ethnic Georgians Only)

References

- EF/CRRC-Georgia surveys on Knowledge of and Attitudes towards the European Union in Georgia, 2009–2017. Datasets available at <http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/>

- Eurasia Partnership Foundation. 2015. Knowledge of and Attitudes towards the EU in Georgia: Trends and Variations 2009 –2015, available online at http://www.epfound.ge/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/eu_attitudes_survey_eng_nov_24_1.pdf

About the Author

Tinatin Zurabishvili holds a PhD in the Sociology of Journalism from Moscow M. Lomonosov State University. From 1994–1999, Tinatin worked for the Levada Center in Moscow. After returning to Georgia in 1999, she taught various courses in sociology for the BA and MA programmes in Telavi State University and the Tbilisi State University Center for Social Sciences. In 2001–2003 she was a Civic Education Project Local Faculty Fellow; from 2010–2012, she was a professor at the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs (GIPA). In 2007, she joined the Caucasus Research Resource Centers (CRRC) as a Caucasus Barometer survey regional coordinator. Since 2012, she has worked as the CRRC-Georgia research director. Her research interests are focused on post-Soviet transformation, sociology of migration, media studies, and social research methodology.

What Kind of Role Should the European Union Play for Achieving Sustainable Peace in Georgia?

By Shu Uchida (University of Coimbra)

Abstract

This contribution discusses the role of the European Union in Georgia, with specific focus on improving the effectiveness of the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM). Now that the situation on the ground is relatively “stable”, what kind of role should the EU play in Georgia for achieving sustainable peace? It stands to reason that the EUMM should focus not only on early warning, since it is necessary but insufficient, but also on other activities, e.g., post-conflict stabilisation. Moreover, this article emphasizes the importance of conflict transformation for addressing protracted conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia via the Incident Prevention and Response Mechanism (IPRM), which was established in tandem with the Geneva International Discussions.

Introduction

On August 7, 2008, Georgia tried to forcefully incorporate South Ossetia into the Tbilisi Administrative Territory (TAT), which did not include the two breakaway regions, i.e., Abkhazia and South Ossetia, during the time when Russia was holding its Kavkaz 2008 military drill. Russia intervened in the armed conflict and invaded the TAT. For the first time since 1979, Russia’s military crossed state borders to attack a sovereign state. Based on the six-point agreement brokered by the former President of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, the armed conflict ceased and the EU deployed the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM) as an early warning apparatus, although Russia refused to accept the mission inside of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

According to the information extracted from the interview with an anonymous EUMM high-ranking officer in May, 2016, “Local Georgian people have acknowledged the fact that people cannot cross the Administrative Boundary Lines (ABLs) of breakaway regions and this is no longer a temporary situation. Georgian people do not have access to the ABLs now, but the Russian and South Ossetian side have already stopped putting the new fences for demarcation of the ABLs. This is the new reality. In this respect, the situation on the ground is much more stable than before”.

Therefore, this article discusses the EU’s role on the ground in Georgia, with specific focus on improving the effectiveness of the EUMM. Now that the situation on the ground is relatively “stable”, what kind of role should the EU play in Georgia for achieving sustainable peace?

The EUMM is a mission without the direct influence of Russia unlike the United Nations (UN) and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) missions regarding decision making. The function of the EUMM is limited, mainly focusing on monitoring the area excluding Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The mission does not have a mandate for conflict resolution or transformation, although it co-chaired the IPRM meetings for negotiations on security and humanitarian issues among the parties of conflicts for confidence building. Additionally, it has had difficulty in providing material support to the local people on the ground due to the nature of this mandate.

The resumption of the OSCE mission might become a solution for conflict resolution by providing a comprehensive remedy because it usually has a broader mandate. If the OSCE mission would come back, it must heed the amicable relationship with direct parties of the conflicts. However, Russia insists that if the OSCE mission would come back to Georgia, it should open independent offices in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which is totally unacceptable for the government of Georgia. According to an anonymous officer of the EU Special Representative Office, “The OSCE mission would not come back to Georgia in the near future, although we do not exclude the possibility that it might come back as a project-based one, not the whole mission”.

Now that there are few possibilities of resuming the OSCE mission, the importance of the EUMM is unquestionable for achieving sustainable peace in Georgia.

The EUMM

EUMM is an unarmed civilian monitoring mission of the EU. Since deployment, it has patrolled day and night, specifically in the areas adjacent to the ABLs of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The EUMM is headquartered in Tbilisi with field offices in Gori, Mtskheta, and Zugdidi. Its mandate is valid throughout Georgia; however, the de facto authorities of Abkhazia and South Ossetia have denied it access to the territories under their control (EUMM 2014).

The mission’s extensive presence through hotlines ensures it has the capacity to gather accurate and timely information on the situation. When appropriate, this information is disseminated to relevant assistance and response bodies. As such, the EUMM has sufficient capacity to monitor ABLs as an early warning initiative. Furthermore, the mission has the capacity to gather detailed information on security issues.

Even if the EUMM plays an important role for early warning, it would be insufficient if the mission cannot access the possible conflict areas. As discussed earlier, the EUMM can access neither Abkhazia nor South Ossetia. However, they attempt to overcome these constraints through a satellite system. Thus, it is not a major issue anymore. However, there is another constraint of the mission: the mission’s mandate does not allow it to fund economic cooperation projects aimed at post-conflict stabilisation. Improving the Effectiveness of the Mission Concerning the EU’s foreign and defence policies, the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) replaces the former European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP.) Before the Treaty of Lisbon was enacted, tasks that could be conducted under the CSDP framework included the following:

- humanitarian and rescue tasks

- conflict prevention and peace-keeping tasks

- tasks of combat forces in crisis management

The Treaty of Lisbon adds three new tasks to this list:

- joint disarmament operations

- military advice and assistance tasks

- tasks in post-conflict stabilisation (European Union 2010).

Specifically, this research underscores the importance of the last task added by the Treaty of Lisbon, namely, “tasks in post-conflict stabilisation”. It is essential to enhance the EUMM’s capabilities and effectiveness for achieving sustainable peace in Georgia.

To give one example: The “Grassroots Human Security Grant Projects (GGP),” an still ongoing long-term grant scheme initiated by the Embassy of Japan in Georgia, funds local and international NGOs, enabling them to implement projects to stabilize society, e.g., renovating kindergartens for IDPs and clearing landmines. This should be regarded as a form of peacebuilding, because it addresses grassroots issues. The grant amount for each project is approximately 100,000 USD, and the embassy adopts approximately 10 projects each year, totaling approximately 1 million USD per year (Embassy of Japan 2014a). While this amount is relatively small, it could contribute towards strengthening and empowering the local population’s capacity to return to normal life and building resilience against post-conflict challenges. However, the Embassy is not always adequately informed on grassroots issues and sometimes has difficulties in finding reliable organizations to implement projects. Thus, the EUMM provides the Embassy with information and recommendations for project implementation. One EUMM recommendation was a project to construct a social education centre in Nikozi village in the Gori district, which was implemented by the NGO “American Friends of Georgia” and funded by the Government of Japan (Embassy of Japan 2014b). Another project implemented in close collaboration with the mission was aimed at renovating a kindergarten in Khurcha village in the Zugdidi district. These projects were highly appreciated by the local people, as the author’s own interviews have shown. Also, these projects enabled the Embassy of Japan to deepen the ties with the EUMM.

In reality, the mission monitors areas along ABLs, and local people provide it with information on the challenges they experience. However, while the mission accurately acknowledges these challenges, its mandate makes it difficult to provide tangible support for the local people. Consequently, despite a good relationship between the mission and local people, both locals and monitors become frustrated over numerous daily questions. Thus, this research argues that the mission should strengthen relations with other donor embassies, e.g., the Embassy of Japan in the above example, by providing information pertaining to grassroots issues to stabilize society via economic cooperation projects. This should enable a win–win situation for EU–Japanese relations and a win–win–win situation for EU–Japan–Georgia relations.

As many donor countries face the challenge of securing an adequate budget for economic cooperation projects, many will be keen to collaborate with other donors, although until recently, donor countries competed to fly their national flags at project sites. Additionally, most donor countries need accurate information on the issues pertinent to the locals. The mission should utilize this opportunity to strengthen relations with other donors to implement projects and tangibly support the local population through information sharing and collaboration. Furthermore, by providing other donors with the precise information required for project implementation, the EUMM could improve its reputation in local society, which could enhance the environment in which the mission seeks to gather more accurate information from local people. This could create the synergy required to improve the mission’s effectiveness through collaboration with other donors through co-conceptualizing projects and collecting more accurate information. Additionally, collaboration efforts do not require that the mission’s mandate be modified and that the activity is aligned to EU foreign policy such as CSDP, since it can stabilize local society as a peacebuilding activity.

Implication

Nevertheless, stabilizing activities and efforts only in the TAT contain certain risks to fix the status quo of Georgia regarding Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Because of the status of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, conflict transformation is crucial via diplomacy, i.e., confidence building and coordination of interests of direct parties of the conflicts. Thus, this research also discusses the importance of multilateral diplomacy by means of the IPRM as an implication for further research and practice.

On the South Ossetian side, the IPRM meetings, cochaired by the OSCE and the EU in the no-man’s land of Ergneti, have been held on a regular basis for confidence building among stakeholders. However, on the Abkhazian side, the mechanism had not been functioning until May 2016 since the de facto government of Abkhazia declared the EUMM representative persona non grata in 2012 (International Crisis Group 2013). The stakeholders in the IPRM discuss the issues on the ground, e.g., airspace violations, gentlemen’s agreements regarding IDPs and local individuals with respect to freedom of movement at the ABLs between breakaway regions and the TAT, “borderisation” by de facto authorities in breakaway regions and Russia using barbed wire, and a surveillance system to demarcate the breakaway regions. At this venue, stakeholders coordinate their interests and express their concerns for confidence building, and the EUMM has accurate information on the ground and adequate capabilities to facilitate the meetings of the IPRM. Therefore, the EU should further underline the significance of confidence-building measures: the IPRM.

Conclusion

The EU and its EUMM can play a significant role in Georgia, because the EUMM is the only international monitoring mission in Georgia since the expiration of mandates for the UN and OSCE missions to Georgia. Thus, the EUMM should improve its stabilisation capabilities by collaborating with other donor countries, and the EU should further emphasize the importance of confidence- building measures, i.e., Geneva International Discussions and IPRM. Now that the security situation on the ground is relatively “stable”, both further stabilization and conflict transformation are needed to consolidate peace in Georgia. Furthermore, the EU’s role should be supportive of the self-help undertaken by the Georgian government and Georgian people since sustainable local ownership is also the key for long-term peace in Georgia.

The EU is preoccupied with its own issues. Nonetheless, the EU should carefully consider signals from Tbilisi because the EU does not want the region to become volatile again. If the commitment from the EU does not measure up to the demand from the Georgians, Georgia might start looking for another more trustworthy patron, since dependence is vital for small powers such as Georgia. At this moment, there is no other option, except the West, for Georgia to follow. Russia might become an option in the future if Georgia thinks the West cannot be counted on as reliable. In addition, China might be another option for Georgia to depend on at least economically, although there are hardly any historical ties between them.

Consequently, the visa-free regime for Georgians in the Schengen area could be a crucial signal from the EU to Georgia not to alter its diplomatic trajectory. Furthermore, Georgia signed the Association Agreement including the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement with the EU in Brussels on June 27, 2014 (civil. ge 2014). These moves are vital not only for Georgia but also for the EU, since the EU needs to soothe the region because of energy security and for sustainability on the European periphery. Accordingly, both Georgia’s aspirations for Euro-Atlantic integration and the EU’s Eastern Partnership initiatives could reinforce mutual relations. On the basis of this rapprochement, the EU could play a more crucial role for achieving sustainable peace in Georgia and not altering Georgia’s diplomatic trajectory: the Euro-Atlantic integration.

References

- Civil.ge. 2014. “Georgia, EU Sign Association Agreement.” Accessed June 15, 2014. <http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=27417>

- Embassy of Japan in Georgia. 2014a. “Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Security and Cultural Projects”. Accessed July 29, 2015. <http://www.ge.emb-japan.go.jp/english/grassroots/about.html>

- Embassy of Japan in Georgia. 2014b. “Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Security Projects (GGP) in Georgia 1998–2013.” Accessed July 29, 2015. <http://www.ge.emb-japan.go.jp/files/grassroot%20programs/list_of_ projects_2010_2013.pdf>

- European Union. 2010. “Common Security and Defence Policy.” Accessed July 29, 2014. <http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/institutional_affairs/treaties/lisbon_treaty/ai0026_en.htm>

- European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia (EUMM). n.d. “Our Mandate.” Accessed July 9, 2014. <http://www.eumm.eu/en/about_eumm/mandate>

- International Crisis Group. 2013. “Abkhazia: The Long Road to Reconciliation.” Accessed October 23, 2016.https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/224%20Abkhazia%20%20The%20Long%20Road%20to%20Reconciliation.pdf

About the Author

Shu Uchida conducts research on conflict-related issues in Georgia and its peripheral regions at the University of Coimbra as a Marie Curie Early-Research Fellow within the EU-funded ITN “Caspian”. He has spent the last several years working for the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies of Harvard University, the Strategic Research Center of Georgia, the Embassy of Japan in Georgia, the OSCE/ODIHR Presidential Election Observer Mission in Georgia, and other institutions.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.