Contested History: Rebuilding Trust in European Security

30 Mar 2018

By Christian Nünlist for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published in Strategic Trends 2017 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) on 22 March 2017.

Different interpretations of the recent past still cast a negative shadow on the relations between Russia and the West. The Ukraine Crisis was a symptom, but not the deeper cause of Russia’s disengagement from the European peace order of 1990. While the current situation is far from a “new Cold War”, reconstructing contested history and debating missed opportunities are needed today to create trust and overcome European insecurity.

Introduction

History is back. Recent developments have made clear that ghosts from the past still cast a negative shadow on the current political dialogue between Russia and the West. In addition to tensions arising from the present, the fact that Russia and the West subscribe to diametrically opposed narratives on the evolution of the European security order after 1990 prevents a common view on the causes and origins of today’s problems. These different interpretations of the recent past continue to shape the world today.

The Ukraine Crisis was a symptom, but not the deeper cause of Russia’s disengagement from the European peace order of 1990. The collapse of a common perspective on European security originated much earlier. The current confrontation between Russia and the political West and the broken European security architecture must be understood as a crisis foretold. In 2014, the “cold peace” between Russia and the West after 1989 turned into a “little Cold War”.i

This burden of the past bedevils the current debate about Russia’s role in Europe. Historical analogies are often invoked in discussions over the nature of the current state of affairs, or in trying to explain how we arrived from the high hopes of 1989 at the hostilities of today. On the one hand, some observers speak of a “new Cold War” and recommend a return to a strategy of containment, echoing the ghost of US Cold War diplomat George F. Kennan.ii Others even invoke the image of a “Second Versailles”,iii criticizing the alleged humiliation of Russia after 1991 and the absence of a “new Marshall Plan” for Russia in the 1990s.iv On the other hand, commentators complain about Russia’s neo-imperialist appearance, the claim for special treatment, the references to its unique civilization and exclusive spheres of influence.v

These are not purely academic discussions. The Western narrative is also contested by the sitting Russian leader. President Vladimir Putin has often complained that the West promised Moscow it would not accept any of the former Warsaw Pact members into NATO in 1990. He therefore regards NATO’s expansion as a Western betrayal.

Radically different interpretations of the steps that led from cooperation to confrontation complicate a return back to dialogue, trust, and cooperation. A high-level Panel of Eminent Persons (PEP) launched by Switzerland, Serbia, and Germany identified these divergent narratives about the recent past as “a main problem of today’s relations between Russia and the West”. Its report “Back to Diplomacy” (2015) called for a research project that would systematically analyze the different views on the history of European security since 1990 and examine how and why they developed.vi

In this sense, the present chapter aims to make a modest contribution towards placing post-1989 events in their proper historical context – with a view to the confrontation of our day and possible future ways out of the current stalemate. Naturally, the first drafts of history are always based on little empirical evidence. As long as official documents are classified (usually 25-30 years), studies have to rely largely on memoirs and testimonies of eyewitnesses. This first phase of historiography often promotes a politicized history, with former policymakers wanting to put their actions in the best possible light. Recently, however, archives in the US, Russia, Germany, and elsewhere have been opened, allowing solid historiographical interpretations of what was going on behind the scenes in the early post-Cold War period. Contemporary historians can now provide valuable corrections to early myth-making (whether intentional or unintentional) by adding new empirical, archival evidence and a well-founded historical view to the debate.vii

The aim of this chapter is not to place blame on one side as the main culprit for the descent from cooperation to confrontation. Rather, the newly available documentary evidence allows us to better understand analytically the motives, behavior, and actions on all sides and to provide a more nuanced version with more clarity of what really happened behind closed doors from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

This chapter is structured around presenting three central arguments: First, the often-heard historical analogy, suggesting that the current situation should be labeled a “new cold war” is scrutinized, but ultimately rejected as an inaccurate metaphor which is also misleading for shaping current political decisions in the West. Second, I argue that the crux of Russia’s sense of marginalization within the European peace order lies in the failure to implement the Cold War settlement and the common vision of a pan-European, inclusive security architecture – and in misunderstandings about what had been agreed upon in the high-level diplomatic talks between the West and the Soviet Union that ended the Cold War in 1990. Third, I argue that any renewed effort to deal constructively with the other side needs to start with understanding previous missed opportunities and learning from the past. The deeper causes of Russia’s current disengagement from Europe must be discussed and clarified. By exposing myths, reconstructing contested history may contribute towards tearing down the currently poisoned propagandistic echo chambers and creating trust and confidence in the present situation. An open, inclusive dialogue similar to the historic Helsinki process could be a viable way out of today’s crisis.

If it was possible to create the basis for peaceful coexistence in Europe in a cumbersome, multilateral negotiation marathon during the Cold War, this should also be possible in the 21st century – despite, or precisely because of, the currently difficult conditions. However, it should also be remembered that the historic Helsinki process could only be launched ten years after the Berlin Wall had been built and after West and East had accepted their respective spheres of influences in Europe. Today, patience is needed for setting up a similar multilateral exercise within the framework of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Disputed territories and overlapping spheres of influence make the situation today much more complicate.

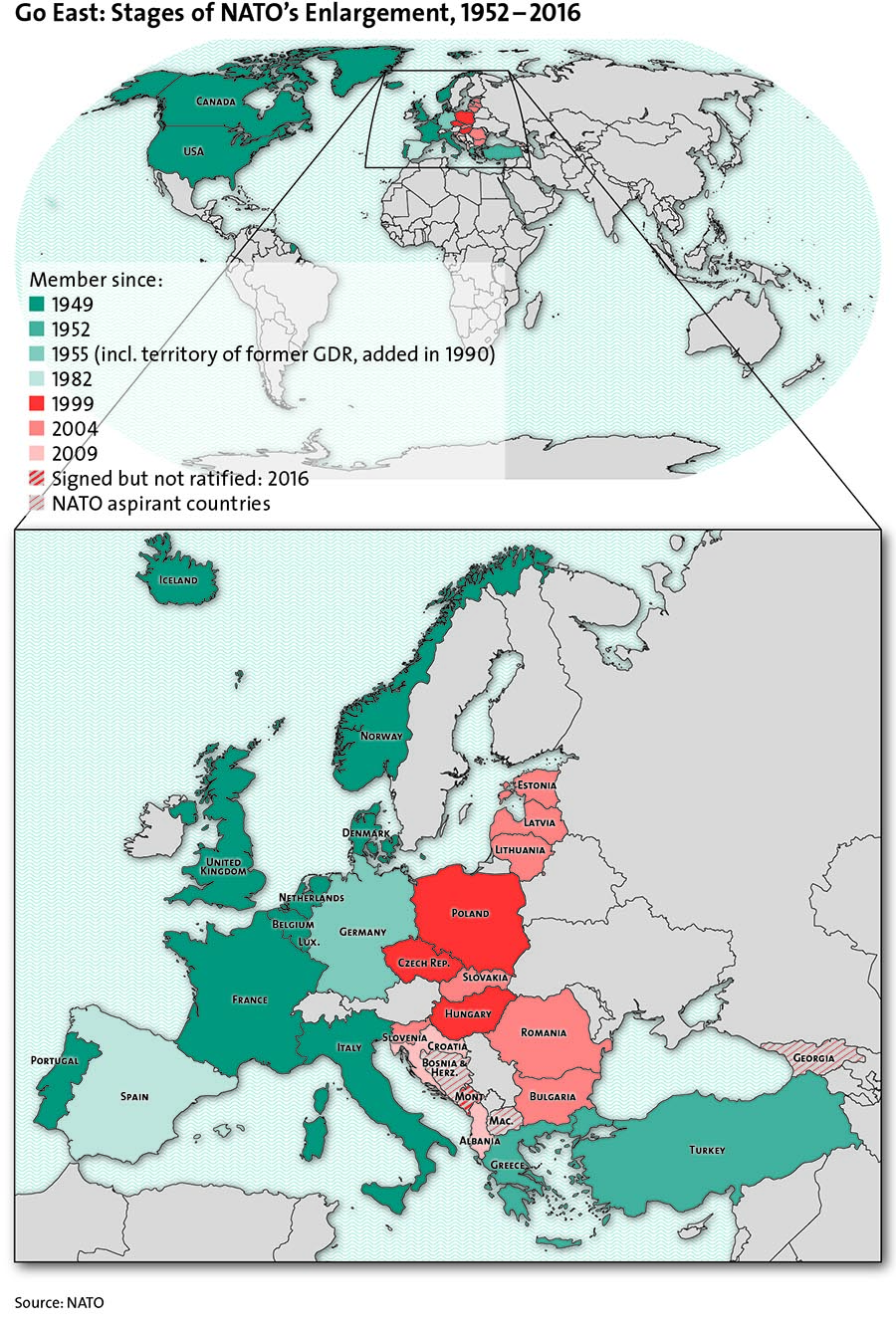

It is opportune now to critically review the terms of the Cold War settlement in Europe in 1990 to better understand the roots of the current confrontation between Russia and the West. The missed opportunity for a successful integration of Russia into European security structures after 1989 puts into perspective the Western narrative of the end of the Cold War, hitherto often portrayed as a success story. While the enlargement rounds of NATO and the EU have provided security and prosperity to Central and Eastern European countries, the failure to find an acceptable place for Russia within the European security framework contributed to a new dividing line in Europe and instability.

A more nuanced understanding of the recent past, as advanced in this chapter, is in no way meant to justify Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014. But it should serve as a reminder that the West and Russia have not yet found a solution to overcome European insecurity and have yet to realize the vision of indivisible European security. Or in the words of Italian philosopher George Santayana (1863–1952): “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”viii

A New Cold War? Characteristics of the Current Confrontation

Russia’s land grab of Crimea and its (initially denied) military intervention in Eastern Ukraine brought back memories of the original East-West confrontation in Europe. Russian Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev said in February 2016 in Munich: “We have slid into a time of a new Cold War”.ix The cognitive recourse to the term “Cold War” has been experiencing a revival since 2014,x but in fact the label had already been used in the media and scholarly publications in the aftermath of both the Russian-Ukrainian gas crisis in 2006 and the Russian-Georgian War in 2008.xi

The historical analogy, however, is misleading when it comes to the characterization of the current relationship between Russia and the West. Ultimately, it is also dangerous, because it implies that the West should respond to the alleged “Cold War 2.0” with well-tried strategies of the past. The original Cold War was a global confrontation between two ideologically antagonistic power centers in Washington and Moscow. The Communist Soviet Union and the democratic, liberal West dominated the international system between 1945 and 1990 and divided the world into two camps. None of three key attributes – orderly camps, ideological superpower contest, global character – apply to the current confrontation between Russia and the West.

First, the current global order is no longer exclusively shaped by the US-Russian confrontation. Today’s international system is radically different from Cold War bipolarity and rather marked by a transition from unipolarity under Western dominance towards multipolarity and the emergence of new power centers in Asia and the global South. The US and Western Europe will remain influential, but they will lose power relative to the emerging powers like China or India. Russia will also play a more active role in Europe than in the 1990s in such a multipolar global order, but it is currently stagnating economically. In contrast to the Cold War era, Europe is no longer the center of US attention – US grand strategy is increasingly geared towards a strategic rivalry with rising China. Russia is a regional spoiler, but no longer constitutes the principal global challenge for the US and its allies as the Soviet Union did during the Cold War. Russia is no longer the hegemon of a strong military pact. In fact, Belarus and Kazakhstan even drew the lesson from the Ukraine Crisis to strengthen their independence from Moscow. Increasingly, these two countries see themselves not so much as partners of Russia, but rather as mediators between the West and Moscow.xii Finally, the current confrontation is more limited in geographical scope and mainly focused on Greater Europe.

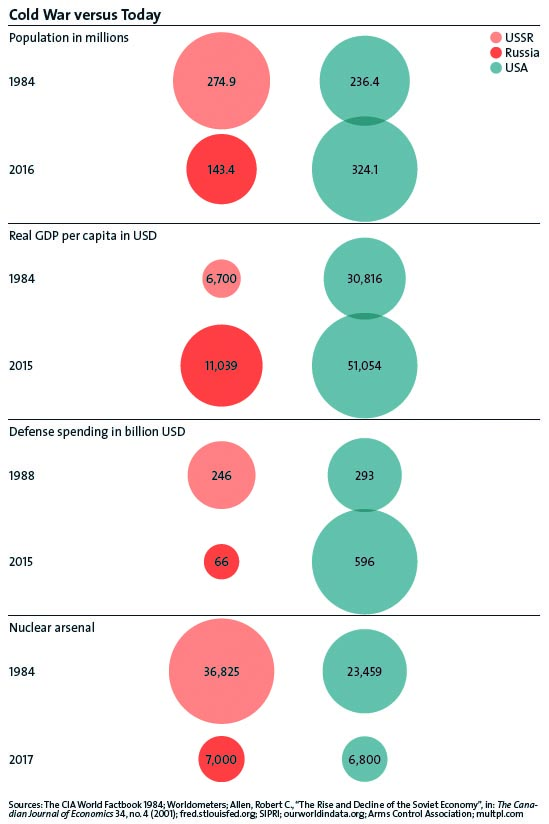

Second, today, there is no risk of a remake of an ideological competitive global struggle between communism and capitalism – modern Russia is capitalist as well. Russia is not leading a global anti-Western camp, although Putin poses as the leader of a Slavic-Orthodox world and likes to speak of a war of the “West against the rest.”xiii He sees in Russia the true heritage of a conservative European civilization shaped by Christianity.xiv In addition, Russia is significantly weaker than the Soviet Union was. Compared with the territory and population of the Soviet Union, Russia “lost” 5.2 million square kilometers and about 140 million inhabitants after 1991. Russia’s armed forces were reduced to about a fifth of the Red Army’s strength during the Cold War. Russia’s defense budget (2017: US$45.15 bn) is over 17 times smaller than the US defense budget (US$773.5 bn).xv In addition, Russia’s economic power also contradicts talk of a renaissance of a superpower rivalry – even if the US always had a clear upper hand in economy during the Cold War. But the gap widened dramatically after 1991. Currently, Russia is only the 12th-largest economic power (US$1.3 bn), even behind Canada and South Korea, while the United States (US$18 bn) is still the world’s top economic power, ahead of China.xvi In the last few years, Russia’s economy has suffered primarily as a result of falling global oil prizes as well as due to Western sanctions.xvii Russia’s significant overall inferiority to the US and the West is compensated by its possession of nuclear weapons and its veto power in the UN Security Council, as well as economic strength in individual sectors such as gas, oil, coal, and timber.xviii

Third, many parts of the globe are not affected by the current Russian-Western confrontation. China, India, Brazil and others have so far refused to take sides in the conflict between Russia and the West. After 2014, Russia and the US continued to cooperate when their interests overlap, for example in the containment of Iran’s nuclear program, the stabilization of Afghanistan, the Middle East peace process, the fight against jihadist terrorism, or climate change. However, the poisoned relations between the US and Russia have already negatively impacted the international community’s response to the Syria War.

Structurally, therefore, the current conflict differs greatly from the Cold War – and might be described rather as a regional contest over European integration models rather than a global ideological and military rivalry. In contrast to the original Cold War, the current conflict between Russia and the West is not yet predominantly militarized, despite Moscow’s occasional nuclear saber-rattling. It is true that Russia is implementing a multi-year modernization program of its armed forces, and the West has strengthened NATO’s eastern flank military. But neither side has the military capacity any longer for launching a major military offensive in Europe (on the scale of Cold War scenarios for a war in Central Europe), and no new military arms race has yet been observed. Military scenarios mostly focus on the Baltic States, where Russian forces could embarrass Western forces should Putin decide to ignore NATO’s Article 5 commitment – which would be a very risky gamble.xix

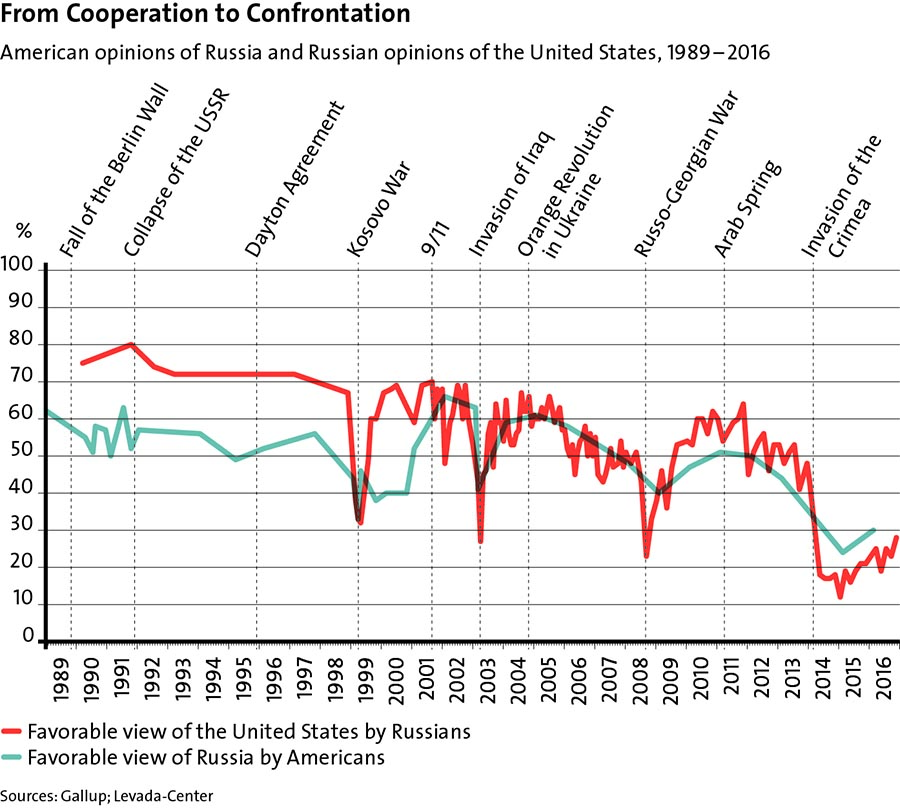

The current situation can be best characterized as a fragile and uneasy mix of conflictual elements (dominant since 2014), confrontational elements (not yet dominant), and cooperative elements (occasional, isolated events). Isolated cooperative events, however, are only transactional and no longer transformative. Currently, both sides favor deterrence over cooperative security, and most formal communication channels were closed in 2014.xx

And yet, as Robert Legvold has pointed out in his book “Return to Cold War”, the behavioral patterns of Russia and the West are becoming more and more similar to the Cold War era. In the dominant Russian and Western narratives, the other side is blamed for everything and all, and is held responsible for the erosion of the post-Cold War peace order in Europe. A solution to the conflict is therefore only considered to be possible if the other side capitulates or radically changes its behavior.xxi

The common vision of an undivided, inclusive, and cooperative Europe seems to be an aspiration from a very distant past. However, the renewed security dilemma actually already originated in the aftermath of the end of the Cold War, when Russia and the West failed to implement a mutually acceptable European security arrangement.

From Cooperation to Confrontation: The “Western Betrayal of 1990” Revisited

The current crisis in European security needs to be contextualized within a complex historical process that started at the end of the Cold War. In recent studies revisiting the descent from cooperation into confrontation, the following scholarly consensus is slowly emerging, based on newly available archival evidence: Both sides are responsible for the fact that the common strategic vision of 1990 could not be implemented in a sustainable matter.xxii Mistakes were made on both sides, but some of the more fatal long-term developments largely resulted from unintended side-effects of crucial decisions that seemed to make perfect sense for the respective side at the time – for example, the Western desire to expand the area of liberal democracy and market economy to the East to increase international stability. Not unlike to the similarly complex historical process of the transition from World War II cooperation to Cold War antagonism between the US and the Soviet Union after 1945, misperceptions, misunderstandings, and self-delusions on both sides complicated Russian-Western relations after 1989.

On the one hand, doubts emerged early on in the West as to whether Boris Yeltsin’s desire to transform Russia into a democratic market economy that was integrated into the West could really be fulfilled. Western hopes were dashed by Yeltsin’s military assault on the Russian parliament in October 1993 and Moscow’s brutal action in the Chechen War in 1994. The parliamentary elections of December 1993 gave evidence of rather massive domestic resistance in Russia to Yeltsin’s pro-Western reform course. As a result, NATO security guarantees moved up on the political agenda of Central and East European countries, as a safeguard against possible future Russian revanchism in Europe. The West also felt an obligation to support their transition into full-fledged members of the Western security institutions. After the dissolution of the USSR and the Warsaw Pact, a dangerous security vacuum had opened up in Europe.

The US and the West still supported Russia in its reform efforts towards a Western market economy and democracy. But there was “no new Marshall Plan”.xxiii Western support for Russia in the 1990s was “too little, too late”, even if Russia was allowed to join the G7 in 1997, thus transforming this exclusive club of the world’s leading industrial powers into the G8.xxvi In addition, Russia also claimed a special status in its relations with NATO and the EU compared to other post-Communist states, due to its size, geographical extension, nuclear superpower standing, and its permanent UN Security Council seat. The case for Russian membership in NATO or the EU was occasionally put forward, but Russia was always considered too powerful, too special, and too different to be successfully integrated into Western organizations.xxiv

On the other hand, the US could not resist the temptation to take advantage of the Soviet Union’s strategic withdrawal from Central and Eastern Europe after 1989. The essence of Russian grievances against the West is the alleged “betrayal of 1990”: At that time, as Putin underlines to this day,xxv the US had promised in high-level negotiations leading to German reunification not to expand NATO further to the East – “not an inch”, in US Secretary of State James Baker’s famous words addressed to Gorbachev in February 1990. Therefore, Russia regards NATO’s Eastern enlargement as a Western betrayal. The minutes of the respective bilateral meetings between US, West German, and Soviet leaders can now be accessed in archives in Washington, Berlin, and Moscow. They reveal that the West did not offer a clear, legally binding promise to Moscow not to expand NATO eastwards. These talks focused on German reunification and the territory of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1990. A future NATO membership of Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia was not discussed. A dissolution of the Warsaw Pact was still unthinkable at that time.

Later Russian criticism about a “broken promise” is thus based on a myth and not on verifiable documentary evidence. Non-expansion promises were only given with regard to the GDR, which as part of reunified Germany would become a member of NATO, but with a special military status.xxvii

A close reading of the 1990 statements by US President George H. W. Bush, Secretary of State James Baker, and German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, based on recently declassified governmental documents, however, suggests that NATO’s later Eastern enlargement indeed “broke” at least the cooperative spirit of the Cold War settlement. In 1990, Bush and Baker promised Gorbachev they would transform NATO from a military alliance into a political organization and reform the CSCE into the main European security forum. Genscher also promised to transform the CSCE into the dominant security alliance in Europe, replacing the Cold War military alliances NATO and the Warsaw Pact. In 1990, Genscher (and his advisors such as Dieter Kastrup, head of the Political Department, and State Secretary Jürgen Sudhoff) earnestly wished to establish a new security order in Europe, modeled after the CSCE. To honor Western partnership with Moscow, he was even ready to dissolve NATO together with the Warsaw Pact. His “promises” to his Soviet counterparts were therefore meant sincerely. Nevertheless, Genscher could speak neither for Chancellor Helmut Kohl nor for NATO, let alone for Warsaw, Prague, or Budapest.xxviii

French President François Mitterrand on 31 December 1989 also offered East Europeans a “Confederation for Europe” under France’s auspices as an alternative to eventually joining the European Community. Mitterrand’s project intended to include the Soviet Union, but to exclude the US.xxix In addition, Eastern European countries initially also pointed to the CSCE as the preferred structural design for the future European security architecture. In February 1990, for example, Czechoslovak President Vaclav Havel called for all foreign troops to leave Eastern Europe and favored the replacement of NATO and the Warsaw Pact with a pan-European organization along CSCE lines. At that time, Poland also thought a new European security structure would supersede both Cold War alliances – and agreed with Gorbachev’s plea that the Warsaw Pact should be preserved, since it was needed, in Poland’s view, to guarantee its borders.xxx

The US, however, resisted these calls for pan-Europeanism by Gorbachev, Genscher, Mitterrand, Havel, and others. The Bush administration internally decided in early 1990 that the new security order in Europe should not be completely different from the Cold War order. The future security architecture should not be centered around a new, pan-European security organization based on the CSCE. For Washington, the exclusive NATO (without Russian membership and without a Russian veto) should be preserved as the most important instrument for stability and peace in Europe – and for continued US dominance in European security. Already in the summer of 1990, the possibility of a NATO membership of Eastern European states began to play a role in internal planning and debates in Washington. Bush’s advisors emphasized that strengthening the CSCE at the expense of NATO was out of the question. In July 1990, Baker bluntly warned Bush that “the real risk to NATO is CSCE”.xxxi Rather than to create a truly new international order, the US instead preferred to perpetuate Cold War institutions that it already dominated.xxxii

In its diplomacy with Moscow, Washington still assured Gorbachev that the West would limit NATO’s influence and instead strengthen the pan-European CSCE. In several public speeches and in meetings with their Soviet counterparts, US leaders promised that European security would become more integrative and more cooperative – and NATO less important. Talking to Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze on 5 May 1990, for example, Baker promised to build a “new legitimate European structure – one that would be inclusive, not exclusive.”xxxiii

The informal Cold War settlement reached in 1990, however, did not last very long. Actually, it collapsed already one year later. Instead of the Soviet Union, the West was now facing a much weaker Russia. After the disintegration of the USSR, Moscow was no longer an equal partner in the debates about shaping the future security order in Europe.xxxiv In the 1990s, the US no longer perceived Russia as an ideological or military rival. The emerging European security architecture became US-dominated and was largely based on the status quo with NATO as its central pillar (as desired by Bush’s advisors in mid-1990).

From a Western perspective, hopes were still high in the early 1990s that Russia could be integrated into the emerging European security system. Russia was no longer treated as an adversary. At NATO summits in London (1990) and Rome (1991), the vision of Russia’s future integration into the Euro-Atlantic security community was still upheld. Under the label “new world order”, the new cooperative spirit between the former Cold War rivals was successfully implemented in the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein in 1991. Nevertheless, the planned transformation of NATO from a military pact into a political organization was put on hold after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and after war had broken out in the Balkans. Fear of a return of Russian imperialism and expansionism led Eastern Europeans in particular to push for NATO enlargement. NATO was preserved as an insurance policy against a future resurgent Russia. The administration of US President Bill Clinton worked hard to have Russia support the Western military intervention and peacekeeping mission in Bosnia (IFOR) in 1995–6. Russia joined UN sanctions against Serbia and Montenegro and agreed to suspend the OSCE membership of these two countries in 1993. In the spirit of cooperative security, the Kremlin also gave a green light to the OSCE’s deployment of an assistance group to Chechnya in 1995.xxxv

NATO’s eastern enlargement was sold to Russia as a win-win solution, since extending NATO membership to Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic would also increase stability on Russia’s western border. NATO expansion, desired by Central and Eastern European governments and strongly supported by the US and Germany, was compensated with a special NATO-Russia partnership format – the NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council (PJC), established in 1997 – as well as with a Western invitation for Russia to join the exclusive G-7 club (1997).

From a Russian perspective, NATO expansion led to a European security architecture that was increasingly built against, rather than with, Russia – despite Western good intentions to stabilize Mitteleuropa and despite the establishment of privileged partnership formats between NATO and Russia. With each further NATO expansion round, the 1989 vision of a “Europe whole and free” (George H.W. Bush in Mainz) contrasted with the isolated position of Russia. Moscow had a voice in European security, but no veto. While Central and Eastern European states joined NATO and the EU, Russia was left outside of these security institutions. Europe appeared to be divided again between East and West, with a new demarcation line moved further to the east than the original Iron Curtain – now running from Narva in the Baltic to Mariupol on the Sea of Azov.

Increasingly, the Kremlin perceived the evolution of European security as zero-sum-game rather than a cooperative undertaking. Russia felt particularly betrayed by the Clinton administration’s move from a policy of NATO partnership for all (including Russia) towards NATO membership for some in 1994. As a recently declassified memorandum of conversation makes clear, US Secretary of State Warren Christopher promised Yeltsin on 23 October 1993 in Moscow that nothing would be done to exclude Russia from “full participation in the future security of Europe”. Presenting US plans for a NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP), Christopher emphasized that PfP would be open for all former Soviet and Warsaw Pact states, including Russia, and “there would be no effort to exclude anyone and there would be no step taken at this time to push anyone ahead of others”. When a relieved Yeltsin learned that the US would only offer partnership rather than membership or an associate status to Central and Eastern European countries, he told Christopher that this was a “really great idea” and a “brilliant stroke” that would remove all the tension that had existed in Russia regarding NATO’s response to Central and Eastern European alliance aspirations.xxxvi

When Clinton told Yeltsin in September 1994 that NATO would soon expand, Yeltsin felt betrayed, having been given the promise of “partnership for all, not NATO for some” by Christopher less than a year earlier. He used a CSCE meeting in Budapest in December 1994 to warn his Western colleagues that Europe was “risking encumbering itself with a cold peace”. Emphasizing that Russia and the West were no longer adversaries, but partners, he emphasized that the plans to expand NATO were contrary to the logic not to create new divisions, but promote European unity.xxxvii

Throughout the 1990s, Russia advanced proposals and ideas for a transformation of the CSCE/OSCE into a regional security organization that was legally incorporated, with a legally binding charter, and a European Security Council based on the UN model. From the Russian perspective, weakening NATO and the US role in Europe was part of the thinking.xxxviii These Russian reform proposals were all rejected by the West and disappointed Russian hopes that the CSCE/OSCE would become the center of the European security system as promised by the West in 1990. The emergence of the weakly-institutionalized OSCE in 1995 also disappointed Russian hopes for a new pan-European security organization.xxxix

The worldviews of Russia and the West visibly collided in the spring of 1999. Yeltsin strongly criticized the unilateral military action of the West – without a UN Security Council mandate – against Serbia in the Kosovo War. Russia had been a member of an international contact group with the US, France, Britain, Germany, and Italy trying to mediate a diplomatic solution. Moscow accused the West of breaching the Helsinki principles of territorial integrity and inviolability of borders.xl

After “color revolutions” in Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004), and Kyrgyzstan (2005) and under the impression of George W. Bush’s “freedom agenda”, in a speech delivered in early 2007 at the Munich Security Forum, Putin stigmatized the OSCE as a “vulgar instrument” of the West, aiming at advancing Western interests at Russia’s expense. He meant the OSCE’s election monitoring missions and field missions to verify compliance with human and civil right commitments. These missions were increasingly criticized by Moscow as an unacceptable interference in internal affairs and as violations of state sovereignty.xli The Arab rebellions and Western military intervention in Libya in 2011 marked another step, in Russian eyes, from cooperation to confrontation.

Then again, Putin’s anti-Western volte-face in 2011–2 can maybe best be explained in terms of domestic policy. Renewed emphasis on Russia’s identity as a Eurasian, Slavic, Orthodox power was an important element in Putin’s presidential election campaign.xlii To avoid mass-protests and a regime change in Moscow, Putin advanced anti-Western rhetoric for a rally-around-the-flag effect and to deflect domestic attention from structural economic problems in Russia. Thus, many Russia experts are convinced that Putin’s fear of a “color revolution” in Moscow, inspired by the “Maidan protests” in Kiyv, was an important motive for intervening militarily in Ukraine.xliii The strengthening of authoritarian rule in Russia under Putin, in contrast to the values of the Charter of Paris, contributed to the mounting crisis between Russia and the West.

In retrospect, the window of opportunity for truly cooperative security between Russia and West had already closed by early 1992, after the Soviet Union had collapsed. European security now became US-dominated and NATO-centered. The Cold War settlement of 1990 and the vision of an inclusive, pan-European new security architecture, as promised by the George H.W. Bush administration and German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, never materialized. The relations between Russia and the West deteriorated in stages, and tense relations were interrupted by at least four “resets” and fresh starts to improve cooperation.xliv But these “honeymoons” never lasted long – and in the end, the key question of Russia’s role in European security was avoided and not seriously discussed. By 2008, Russia had given up hope of playing an active, equal role in Euro-Atlantic Security. Putin began looking for an alternative project where Russia would be a regional hegemon in the post-Soviet space.xlv Since 2014, the issue of how to deal with Russia has returned to the political agendas of the West in a most dramatic fashion.

Rebuilding Trust: Thoughts on the Future of European Security

A look back can help us to understand Russia’s present and future role in Europe. The history of the Helsinki Process and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE, 1972–94) encourages hope that a new transformation from conflict to cooperation might again be possible in a peaceful way and in an inclusive, multilateral diplomatic setting – just as it was in the 1970s and 1980s, when East and West, despite their intense strategic rivalry, were able to conduct a pragmatic dialogue to reach consensus on the most important security issues in Europe. No side benefits from a permanent state of confrontation. Communication is important for de-escalation, and dialogue is an important prerequisite for détente. It needs to be emphasized that dialogue is not the same as appeasement, and that listening to and trying to understand the other side’s grievances is not the same as taking them at face value.

Much like the CSCE in the Cold War, the OSCE today seems to be the best-suited forum for such a sustainable, permanent exploration of practical ways for carefully managing the current volatile confrontation with Russia, while defending firmly Western interests and values.xlvi The deep causes of mutual mistrust between Russia and the West need to be discussed and clarified. It is essential to understand the precise reasons for Russia’s long-standing adversarial relationship with the West. The Helsinki Process – an open, inclusive dialogue among all parties of a conflict – is an interesting model for slowly rebuilding trust that was destroyed in the last two decades and for returning to a more constructive Western-Russian relationship. Such a reconciliation process, however, is lengthy and requires patience. Instead of ignoring or deriding alternative narratives, they should be actively tackled and changed. Insights into mistakes made in the past and missed opportunities might help us rediscover a mutually acceptable vision for peaceful coexistence in Europe.

At the same time, supposedly attractive alternatives to multilateral, cooperative security such as a “Yalta II” agreement must be unmasked as misleading historical analogies. A “Yalta II”, a new great-power agreement like the one reached on Crimea in 1945 between the “Big Three” (Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill) to define and recognize boundaries and spheres of interest, seems an impractical notion. Anyone seriously entertaining the historical analogy would soon remember that a new Yalta pact first requires another world war, and that a new Yalta pact would be diametrically opposed to the 1975 Helsinki principles and the spirit of the OSCE.xlvii Recently, the idea that US President Donald Trump might be open to the idea of a “Big Two” deal with Putin – much to the consternation of America’s (Eastern) European allies, who fear an arrangement concluded without their participation and at their expense – was put into perspective again and the initial euphoria in Moscow with Trump’s victory is already evaporating.xlviii

Achieving consensus among OSCE participating States on a new negotiation process aimed at formulating a “Helsinki II” is currently unrealistic. After all, the principles of the 1975 Helsinki Final Act have been negotiated between East and West and are thus universal, not Western principles. The “Helsinki Decalogue” has served its purpose well for over four decades. In this respect, the Panel of Eminent Persons (PEP) report of 2015 – employing an apt metaphor – argues that the rules of traffic don’t have to be changed just because one driver ran a red light.xlix However, there is a need to discuss the different views as to how these principles (e.g., non-use of force or self-determination) must be interpreted in the current situation. Their interpretation as substantiated in the 1990 Paris Charter for a New Europe has been overtaken by events. An informal dialogue in the OSCE could aim at drafting substantiation of the Helsinki principles for the 21st century, a “Paris II”, so to speak, to be formally codified again at future OSCE summit, maybe in 2020, celebrating the 45th anniversary of the Helsinki Final Act.

In the meantime, cooperation between the West and Russia will be limited to selective, interest-based, transactional cooperation. A return to broader cooperation is dependent on a consensus in the Ukraine Crisis and a face-saving exit strategy for Russia from Ukraine. This seems to be unrealistic for the time being, because neither the newly appointed US President Trump nor Russian President Putin before his re-election in 2018 can afford to be accused of weakness or appeasement.l The fact that the West insists on penalizing Russia for annexing Crimea and breaking international law and the Helsinki principles is understandable. However, in the long run, it is more important that the Russian annexation of Crimea (similarly to Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence – despite all important differences between the two cases)li are regarded as disputed exceptions to the still generally accepted principle that borders in Europe can only be changed by mutual consent of the motherland and the regional population, and only peacefully.lii It is better to have two individual cases of disputed exceptions than a generally ignored and violated core principle.

A first trust-building step on the lengthy road back from conflict to cooperation beyond interest-based transactional cooperation was made in December 2016 at the OSCE Ministerial Council with the “mandate of Hamburg”.liii Now, in 2017, the Austrian OSCE Chairmanship is tasked with organizing an informal, structured dialogue on different threat perceptions and security issues in Europe. Another innovative possible step for a return to dialogue was recently proposed by the Panel of Eminent Persons (PEP), a wise men committee tasked by the OSCE Troika of Switzerland, Serbia, and Germany in 2015 to draw lessons from the Ukraine Crisis for the OSCE and European security. In its follow-up report, the PEP in December 2016 suggested that the OSCE Strategy to Address Threats to Security and Stability from 2003 be updated to reflect the changes in international security since then.liv

The aims of such a multilateral dialogue should include a better understanding of the past grievances of the other side, i.e., the different views and interpretations of events in Europe since 1990 and the different views on the causes of the breakdown of trust. In learning from the past, a return to the vision of a commonly shared security community in Europe also requires tackling the difficult question of Russia’s role in European security. A sustainable and stable peaceful European security order should be based on the original rationale and spirit of the Cold War settlement, namely that indivisible security in Europe needs to be built together with Russia – and not against Russia. In retrospect, moving up the timetable for exclusive NATO enlargement (which upset Russia) rather than sticking to the inclusive Partnership for Peace strategy (which was welcomed in Moscow in 1993) might not have been the wisest strategy of the West in the mid-1990s – as historians like George F. Kennan cautioned at the time. In 1996–7, the 92-year old Kennan warned that NATO’s expansion into former Soviet territory was the “most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era” and a “strategic blunder of potentially epic proportions”.lv

History can be a guide towards a richer understanding of past policy decisions; but it should not serve as an excuse for Putin’s illegal military intervention in Ukraine in 2014. Russia needs to recognize that the notion of spheres of influence, demarcated to end any further NATO enlargement into the former Soviet space and (semi-) autocratic regimes, contradicts fundamental, universally accepted ideas of sovereignty, equality, and the freedom of states to choose their alliances. Great-power politics and new Yalta deals are ghosts from the past that should remain in history books about the 19th and 20th century.lvi Patiently bringing back Russia to the rules-based Helsinki order will not be possible overnight – and it might in fact only be realized after the Putin and the Trump years.

Respectful discussion of facts while maintaining divergent opinions has become more difficult in the world today. In an increasingly fragmented, polarized, and politicized media landscape, facts seem to matter less and less, as fake news, the use of trolls, or automated social media bots proliferate. It may seem naïve to hope that scholarly discourse over the recent past will contribute to overcoming grievances over the evolution of European security after 1990. However, particularly to avoid slipping into a “post-truth” world influenced by “alternative facts”, European societies need to invest in education and media literacy.lvii A historical understanding of Western policy after 1989, based on available and valuable archival sources, is also highly relevant for Western relations with Russia today – to counter harmful propaganda and hostile rhetoric on both sides with realistic judgment, based on a sound understanding of empirical historical facts.

The history of the Helsinki Process impressively demonstrates that positive change is possible in the long run, if dialogue with rivals and inclusive, multilateral diplomacy are kept alive also in times of crisis and tension. In addition, Western governments and societies need to be more self-confident in the superiority of their liberal, rules-based international model over illiberal alternatives that envisage a return to the concert of great powers. If the past is indeed the prologue of the future, this is the most important lesson today’s policymakers should draw from the complicated history of how the Cold War was overcome in a peaceful way.

Notes

i Richard Sakwa, external page“Reflections on Post-Cold War Order”call_made, in: Thomas Frear and Lukasz Kulesa (eds.), Competing Western and Russian Narratives on the European Order: Is there Common Ground? (London/Moscow: ELN/RIAC, 2016).

ii See e.g. Alexander J. Motyl, external page“The Sources of Russian Conduct: The New Case for Containment”call_made, in: Foreign Affairs Blog, 16.11.2014; Matthew Rojansky, external page“George Kennan Is Still the Russia Expert America Needs”call_made, in: Foreign Policy Blog, 22.12.2016; Stephen Kotkin, external page“What would Kennan do?”call_made, in: Princeton Alumni Weekly, 02.03.2016.

iii Sergey Karaganov, external page“Time to End the Cold War in Europe”call_made, in: Russia in Global Affairs, 28.04.2014. For a critical discussion, see Patrick Nopens, external page“Beyond Russia’s ‘Versailles Syndrome’”call_made, in: Egmont Security Policy Brief, 25.11.2014.

iv Dmitry Suslov, external pageThe Russian Perception of the Post-Cold War Era and Relations with the Westcall_made, Lecture given at Harriman Institute, Columbia University, 09.11.2016.

v See e.g. Anne Applebaum, external page“The Myth of Russian Humiliation”,call_made in: The Washington Post, 17.10.2014; Michael McFaul, external page“The Myth of Putin’s Strategic Genius”call_made, in: The New York Times, 23.10.2015.

vi Panel of Eminent Persons (PEP), external pageBack to Diplomacycall_made (Vienna: OSCE, 2015), 2.

vii See e.g. Frédéric Bozo et al., “On the Politics of History, the Making of Deals, and the Way the Old Becomes the New”, in: Fréderic Bozo et al. (eds.), German Reunification: A Multinational History (London: Routledge, 2016), 1-11, here at 1ff.

viii George Santayana, The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 284.

ix Henry Meyer et al., external pageRussia's Medvedev: We are in 'a New Cold War,call_made in: Bloomberg Business, 13.02.2016.

x See Dmitri Trenin, external page“Welcome to Cold War II”call_made, in: Foreign Policy, 04.03.2014; external page“The New Cold War”call_made, in: The Guardian, 19.11.2014; Robert Legvold, Return to Cold War (Cambridge: Policy, 2016). Trenin later changed his mind and now emphasizes that he does not find the Cold War analogy very useful. See Dmitri Trenin, Should We Fear Russia? (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 2.

xi See external page“Putin’s Cold War: Using Russian Energy as a Political Weapon”call_made, in: Der Spiegel, 09.01.2006; Edward Lucas, The New Cold War (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

xii Pal Dunay, “The Future in the Past: Lessons from Ukraine for the Future”, in: Samuel Goda et. al. (eds.), International Crisis Management (Amsterdam: IOS, 2016), 162-172.

xiii See Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest (London: Allen Lane, 2011).

xiv Andrew Monaghan, external page“A New Cold War?”call_made, Chatham House Research Paper, 05.2015, 5f.

xv external page“U.S. Military Budget: Components, Challenges, Growth”,call_made in: The Balance, 26.10.2016. However, the GDP share of defense in Russia (budget 2017: 3.3 percent) is comparable with the situation in the US. See external page“Russian military spending cut significantly”call_made, in: Russia & India Report, 02.11.2016.

xvi IMF, external pageWorld Economic Outlook Databasecall_made, 04.10.2016.

xvii World Bank, external pageRussia Economic Reportcall_made 36, 09.11.2016.

xviii Globally, Russia commands over 45 percent of gas reserves, 23 percent of coal reserves, and 13 percent of oil reserves. Quoted in Robert Levgold, Return to Cold War (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 5.

xix David A. Shlapak and Michael W. Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank”, RAND Research Report, No. 1253 (2016). In all of the invasion scenarios used in war gaming the defense of the Baltics, Russian forces reached Tallinn and Riga within 60 hours, leaving NATO with only bad options. The study recommends increasing NATO forces by up to seven brigades.

xx Wolfgang Zellner et al., European Security: Challenges at the Societal Level (Vienna: OSCE, 2016), 18f. See also Dmitri Trenin, The Ukrainian Crisis and the Resumption of Great-Power Rivalry (Moscow: Carnegie, 2014), 3.

xxi Legvold, Return to Cold War, 28ff.

xxii Daniel Deudney and G. John Ikenberry, “The Unravelling of the Cold War Settlement”, in: Survival 51, No. 6 (2009-10), 39-62; Samuel Charap and Jeremy Shapiro, “How to Avoid a New Cold War”, in: Current History 113, No. 765 (2014), 265-271; Levgold, Return to Cold War, 6; Andrew C. Kuchins, Elevation and Calibration (CGI, December 2016). This view is also shared by former political leaders and senior officials including Mikhail Gorbachev, Robert Gates, and Henry Kissinger.

xxiii Angela E. Stent, The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 11.

xxiv Kuchins, Elevation and Calibration, 13.

xxv Andrey Kortunov, “Russia and the West: What Does ‘Equality’ Mean?”, in: Andris Spruds and Diana Potjomkina (eds.), Coping with Complexity in the Euro-Atlantic Community and Beyond (Riga: LIIA, 2016), 83-90, here at 85f.

xxvi Vladimir Putin, external pageAddress by President of the Russian Federationcall_made, Speech, 18.03.2014; Vladimir Putin, external pageMeeting of the Valdai International Discussion Clubcall_made, Speech, 14.10.2014.

xxvii Mark Kramer, “The Myth of a No-NATO-Enlargement Pledge to Russia”, in: Washington Quarterly 32, No. 2 (2009), 39-61.

xxviii Kristina Spohr, “Precluded or Precedent-setting? The NATO Enlargement Question in the Triangular Bonn-Washington-Moscow Diplomacy of 1990/1991 and Beyond”, in: Journal of Cold War Studies 14, No. 4 (2012), 4-54. In the German political system, the Federal Chancellor has the power to determine policy guidelines (“Richtlinienkompetenz”), including on foreign policy.

xxix Liana Fix, European Security and the End of the Cold War: Gorbachev’s Common European Home Concept and its Perception in the West (unpublished manuscript, London School of Economics, 2012), 24.

xxx Vojtech Mastny, “Germany’s Unification, Its Eastern Neighbors, and European Security”, in: Frédéric Bozo et al. (eds.), German Reunification: A Multinational History (London: Routledge, 2016), 202-226, here at 210-213.

xxxi Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion”, in: International Security 40, No. 4 (2016), 7-44 and 31. Similarly, Bush warned Kohl on 24 February 1990 that if the CSCE would replace NATO, “we will have a real problem”. Quoted in Mary Elise Sarotte, “’His East European Allies Say They Want to Be in NATO’: U.S. Foreign Policy, German Reunification, and NATO’s Role in European Security, 1989-90”, in: Frédéric Bozo et al. (eds.), German Reunification: A Multinational History (London: Routledge, 2016), 69-87 and 81.

xxxii Mary Elise Sarotte, 1989: The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009). For a similar view, see Hal Brands, Making the Unipolar Moment: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Rise of the Post-Cold War Order (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016), 279-298.

xxxiii These promises were part of the so-called “Nine Assurances” that James Baker delivered to Gorbachev in May 1990 to get Soviet consent to NATO membership of a reunified Germany. Shifrinson, Deal or No Deal, 29f.

xxxiv Kuchins, Elevation and Calibration, 13.

xxxv James Headley, Russia and the Balkans: Foreign Policy from Yeltsin to Putin (London: Hurst, 2008).

xxxvi James Goldgeier, external page“Promises Made, Promises Broken? What Yeltsin Was Told About NATO in 1993 and Why It Matters”call_made, in: War on the Rocks, 12.09.2016.

xxxvii Ibid.

xxxviii Elena Kropatcheva, “The Evolution of Russia’s OSCE Policy: From the Promises of the Helsinki Final Act to the Ukrainian Crisis”, in: Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23, no. 1 (2015), 6-24. On Gorbachev’s vision of a “common European home”, see Marie-Pierre Rey, “European is Our Common Home: A Study of Gorbachev’s Diplomatic Concept”, in: Cold War History 4, No. 2 (2004), 33-65.

xxxix Kropatcheva, Evolution of Russia’s OSCE Policy, 11.

xl Heinz Loquai, “Kosovo: A Missed Opportunity for a Peaceful Solution to the Conflict?”, in: OSCE Yearbook (1999), 79-92.

xli Vladimir Putin, external page“Monopolare Welt ist undemokratisch und gefährlich”call_made, Sputnik Deutschland, 10.02.2007. On Putin’s „counterrevolutionary obsession“, see Mark Kramer, external page„Why Russia Intervenes“call_made, in: Carnegie Forum on Rebuilding U.S.-Russia Relations, August 2014.

xlii Kuchins, Elevation and Calibration, 19 and 27.

xliii Hanns Maull,“Die Ukraine-Krise und die Zukunft Europäischer Sicherheit”, Lecture, CSS/ETH, 30.06.2015. See also Nicolas Bouchet, „Russia’s ‚Militarization‘ of Colour Revolutions“, in: CSS Policy Perspectives 4, No. 2 (2016); Dmitry Gorenburg, “Putin Isn’t Chasing After Empire in Ukraine; He Fears a Color Revolution at Home”, in: The Moscow Times, 25.09.2014.

xliv As chronicled in Angela Stent’s volume, the first reset was in 1992 between Bush sen. and Yeltsin; the second reset (“The Bill and Boris Show”) between Clinton and Yeltsin in 1993; the third reset between Bush jr. and Putin after 11 September 2001; and the fourth reset between Obama and Putin in 2009. Periods of dialogue and partnership always ended in tense relations and mutual criticism. Stent, Limits of Partnership, x.

xlv Nopens, Beyond Russia’s ‘Versailles Syndrome’, 3.

xlvi Petri Hakkarainen and Christian Nünlist, “Trust and Realpolitik: The OSCE in 2016”, in: CSS Policy Perspectives 4, No. 1 (2016).

xlvii Christian Nünlist, “The OSCE and the Future of European Security”, in: CSS Analysis in Security Policy, No. 202 (2017).

xlviii Timothy Garton Ash, external page“Putin’s Investment in Trump Backfires”call_made, in: Kyiv Post, 17.02.2017.

xlix PEP, Back to Diplomacy, 5.

l Matthew Rojansky, “The Geopolitics of European Security and Cooperation: The Consequences of U.S.-Russia Tension”, in: Security and Human Rights 25 (2014), 169-179.

li For a discussion of why Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008 cannot serve as a precedent for Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014, see, e.g., Christian Weisflog, “Warum die Krim nicht Kosovo ist”, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 18.11.2014.

lii Rojansky, Geopolitics of European Security, 176.

liii OSCE, external pageFrom Lisbon to Hamburg: Declaration on the Twentieth Anniversary of the OSCE Framework for Arms Controlcall_made, 09.12.2016.

liv PEP, external pageRenewing Dialogue on European Security: A Way Forwardcall_made, Report, 23.11.2016.

lv George F. Kennan, “A Fateful Error”, in: The New York Times, 05.02 1997; Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand: A Memoire of Presidential Diplomacy (New York: Random House, 2002), 220.

lvi See Liana Fix, external page„Time for a Helsinki 2.0?”call_made, in: Intersection, September 2015.

lvii See external pageMunich Security Report 2017call_made (Munich: MSC, 2017), 42.

About the Author

Christian Nünlistist a Senior Researcher at the Center of Security Studies (CSS) and head of its think tank team “Swiss and Euro-Atlantic Security”. He specializes in Swiss foreign and security policy, transatlantic relations, and multilateral diplomacy. He is co-editor and frequent author of the policy brief series “CSS Analysis in Security Policy”, which offers a focused discussion of current developments in international security and strategic affairs. In addition, he is the co-editor of the annual “Bulletin zur schweizerischen Sicherheitspolitik".

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.