No 102, Caucasus Analytical Digest: Public Opinion in Georgia: New Caucasus Barometer Results

11 Apr 2018

By Natia Mestvirishvili, Maia Mestvirishvili, David Sichinava and Tinatin Zurabishvili for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Caucasus Analytical Digest on 23 March 2018.

CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer Survey: Introductory Notes

In 2004, the newly established Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) ambitiously attempted to survey the populations of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia and learn about people’s assessments of social and political developments in their respective countries. The Caucasus Barometer project, implemented with initial core funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, proved to be extremely successful. Comparable longitudinal survey data collected from 2008 to 2017—the only data of its kind—and respective documentation are available for researchers and for the general public.

The Caucasus Barometer (CB) story is rich and extensive. Part of it will be told in an upcoming publication entitled, “In the Caucasus we count: Highlights of CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer findings,” which thoroughly analyzes select aspects of the CB data. The present issue of the Caucasus Analytical Digest is the first concise compilation of short articles based on the most recent CB 2017 findings. The survey fieldwork occurred between September 22 and October 10, 2017. A representative sample of 2,379 respondents was interviewed nationwide (with the exception of the occupied territories).

Datasets of all waves of the Caucasus Barometer survey can be accessed external pageherecall_made.

Exploring Public Attitudes Towards Immigrants in Georgia: Trends and Policy Implications

By Natia Mestvirishvili and Maia Mestvirishvili

Abstract

Public attitudes towards immigrants are becoming an increasingly important issue in many countries and are not always positive. In Georgia, CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer survey data show that public attitudes towards immigrants remain quite ambivalent. The changes in reported attitudes between 2015 and 2017 are not necessarily positive. Negative attitudes towards immigrants are more widespread among those who have not had personal contact with immigrants, thus supporting the ‘contact hypothesis.’ The empirical evidence also supports the economic self-interest theory, with higher shares of people living in better-off households reporting positive attitudes towards immigrants in Georgia.

Context: Increased Immigration to Georgia

Numerous studies show that immigrants, if they are well integrated into the receiving society, are not a threat but rather an opportunity for the development of the host countries. It is widely believed that their integration can strengthen international migration’s positive effect as an “engine for social action, dynamism, and fundamental wealth.” (Rodriguez-Garcia 2010, 267) Therefore, the integration of immigrants is a high priority on many developed countries’ policy agendas.

Immigration to Georgia is a relatively new trend, with limited academic and policy work conducted in this field. In the years immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia was a country of emigration; however, recent statistical data demonstrate that Georgia is becoming a country of transit and immigration as well. The number of immigrants in Georgia can, however, only be estimated through fragmented sources that do not always provide a complete and reliable picture.

Georgia’s current immigration regulations (Parliament of Georgia 2014) are quite liberal and do not require immigrants from more than 100 countries who come to Georgia for a period of up to 12 months to apply for residence permits or otherwise register. To legally stay in Georgia for prolonged periods of time, immigrants can simply leave the country once a year and immediately return.

Estimates of different immigrant populations were collected in the 2017 Migration Profile of Georgia. (State Commission on Migration Issues 2017) The United Nations estimated migrant stocks in the country to be 168,802, equal to 4.5% of the total population in 2015. A total of 70,508 residence permits were issued between 2012 and 2016, most of them to citizens of Azerbaijan, Russia, Turkey, Armenia, Ukraine, India, China and Iran. The highest number of residence permits issued over the last five years were work residence permits (32,783) issued mostly to Turkish (24% of the total number), Chinese (22%), Indian (13%) and Iranian (9%) nationals.

In recent years, the number of educational immigrants in Georgia has increased significantly. In 2013, Georgian higher education institutions hosted 4,177 foreign students, while 2016 statistics provided by the country’s Ministry of Education and Science report a number of foreign students that exceeds 9,000, with students coming from 87 countries.

Georgia is also host to a growing number of asylum seekers, refugees and humanitarian status holders. In 2016, there were 414 refugees and 1,099 individuals with humanitarian status, which far exceeds the numbers for 2014—297 and 145, respectively. (State Commission on Migration Issues 2017)

Thus, the available sources confirm that immigration is an increasing trend in Georgia that must be properly addressed. Protecting migrants’ rights, ensuring immigrants’ successful integration into society, and facilitating the peaceful cohabitation of people representing various religious, cultural and ethnic backgrounds are among the main goals anchoring Georgia’s Migration Strategy 2016–2020 (State Commission on Migration Issues 2015), which was developed by the State Commission on Migration Issues. Since integration is a two-way process of mutual accommodation that requires commitment from both host and migrant communities, understanding public opinion in the receiving society is integral to the policymaking process.

Reported Attitudes Towards Immigrants in Georgia, 2015–2017

Globally, public attitudes towards immigrants are not always positive — especially in traditional societies. There is limited research addressing this topic in Georgia, but the existing studies and several anti-immigrant demonstrations in past years suggest that the local population’s attitude towards foreigners is hardly welcoming. (Petraia 2017)

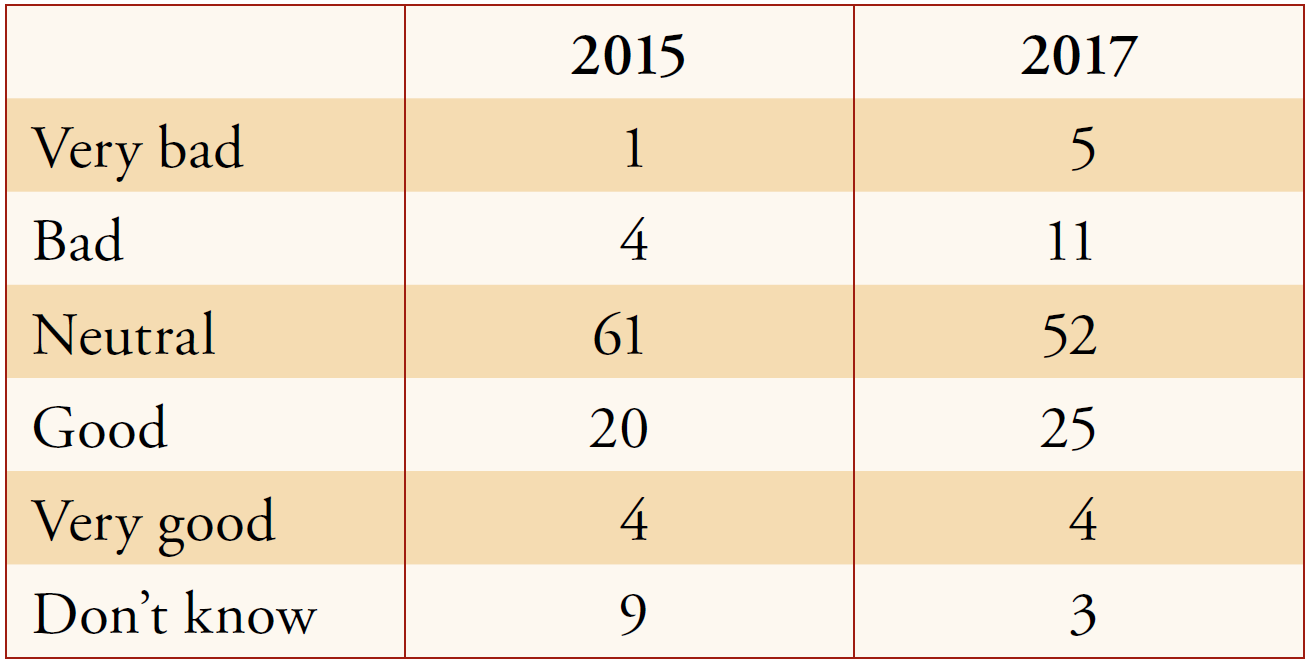

The CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer survey (CB) has attempted to measure the population’s attitudes towards immigrants in 2015 and 2017. Slight changes have been documented during this period. Namely, the share of people who reported neutral attitudes towards foreigners coming to Georgia and staying here for more than 3 months1 decreased from 61% to 52%, while the share of those who characterize their attitudes towards immigrants as bad or very bad increased from 5% to 16% (Table 1), and there were no observable changes in the frequency of reported positive attitudes. These findings might indicate that the population of Georgia is starting to develop more defined attitudes towards immigrants.

Table 1: How would you characterize your attitude towards the foreigners who come to Georgia and stay here for longer than 3 months? (%)

While the reported attitudes towards immigrants do not vary by gender, age does appear to make a difference. Young people in Georgia (those between the ages of 18 and 35) tend to have more positive attitudes towards immigrants than do their older compatriots.

Importantly, CB 2017 data show that a significant share of Georgia’s population (70%) report never having had any form of contact with immigrants. Only 21% of the population reports rarely having contact with immigrants, and 8% reports having personal contact with them often. This finding could be explained by the relatively small number of immigrants in Georgia, but it could also indicate that those who immigrate to Georgia remain quite isolated and have minimal contact with the host community. Regardless, this finding strongly suggests that perceptions of immigrants in Georgia are largely based on information that people obtain from sources other than their own experiences.

Who Tends To Be More Welcoming Towards Immigrants in Georgia?

The two main theoretical approaches explaining public attitudes towards immigrants stem from the disciplines of psychology and economics. The first approach is based on the ‘contact hypothesis,’ which stipulates that interaction with an out-group can be positive and can also lead to friendship between the representatives of the two groups under certain conditions, such as the equal status of the groups, a lack of competition, joint work to achieve common goals and personally knowing each other. (Allport 1954) Later research demonstrated that contact between the representatives of two groups, even when it did not fulfil every precondition, still reduces inter-group prejudice. (Pettigrew/Tropp 2006) Thus, the contact hypothesis remains one of the ‘most durable ideas in the sociology of racial and ethnic relations.’ (Ellison/Powers 1994, 385)

The second theoretical approach emphasizes the primary role of economic self-interest in explaining anti-immigrant attitudes. (Fetzer 2000) Economic self-interest theory states that public attitudes towards immigrants are derived from people’s narrow, material self-interest and suggests that economically disadvantaged individuals are more likely to express anti-immigrant attitudes compared to others who are economically better off, as the former are afraid that their financial well-being may be negatively affected by immigrants. (Hjerm 2001, Verbeck et al. 2002) Some scholars even suggest that economic interest may be the main source of increased opposition to immigrants in developed countries. (Espenshade/Hempstead 1996, Raijman et al. 2003)

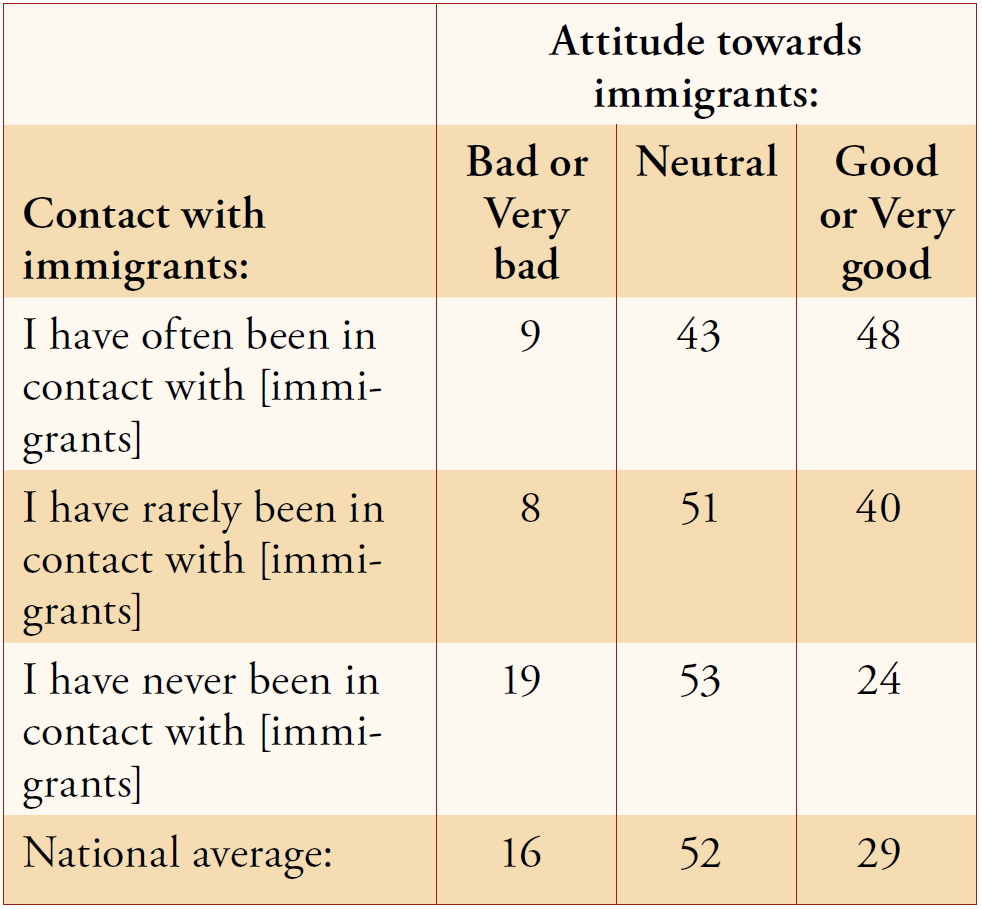

With these two theories in mind, a preliminary analysis of CB 2017 data is presented below. The findings show that people who report frequent or even rare personal contact with immigrants tend to have a better attitude towards them, thus confirming the contact hypothesis (Table 2).

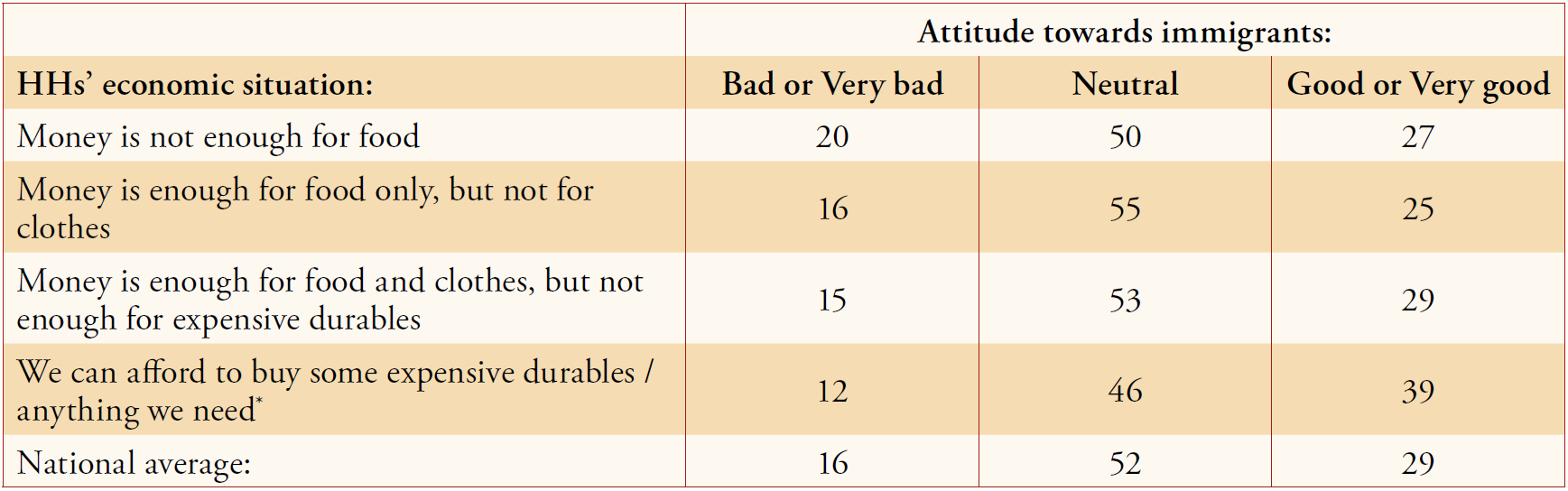

Even though, in accordance with the economic self-interest theory, one would expect employed individuals with higher income to report more positive attitudes towards immigrants, the data show no clear pattern among those who report being employed or those who report a relatively higher personal income. Self-assessments of a household’s economic situation, in contrast, seem to be positively associated with attitudes towards immigrants. Higher shares of people living in betteroff households report positive attitudes towards immigrants (Table 3 overleaf). This is in line with the economic self-interest theory.

Concluding Remarks and Policy Implications

CB 2017 data show that despite the significant financial, social and cultural benefits that immigrants can bring to Georgia, public attitudes towards immigrants remain quite ambivalent. Most people have not had any direct contact with foreigners living in Georgia, which might drive misperceptions and negative attitudes. In fact, negative attitudes towards immigrants are more widespread among those who report no personal contact with immigrants. This finding supports the ‘contact hypothesis’ and suggests that anti-immigrant attitudes in Georgia may not be derived from actual negative experiences but rather from a lack of experience with immigrants. This paper also identifies that, in line with the economic self-interest theory, people living in households of different perceived well-being report different attitudes towards immigrants.

Table 2: Have you had any contact with foreigners in Georgia who have stayed here for longer than 3 months? By How would you characterize your attitude towards the foreigners who come to Georgia and stay here for longer than 3 months? (%)

These findings offer several policy implications. They strongly suggest that integration policy should target both immigrants and the local population. While encouraging immigrants to make efforts to integrate through various mechanisms (such as language courses or vocational training) is vital, targeting the local population and challenging the existing anti-immigrant attitudes through strategic informational campaigns are also crucial. Therefore, it is imperative to create diverse opportunities for interaction between immigrants and locals in a myriad of settings, including socio-cultural, educational, and business spheres.

Table 3: Which of the following statements best describes the current economic situation of your household? By How would you characterize your attitude towards the foreigners who come to Georgia and stay here for longer than 3 months? (%)

Note

1 Immigrants were operationalized in the questionnaire as “foreigners who come to Georgia and stay here for longer than 3 months.” In this article, the term “immigrants” is most commonly used instead.

Bibliography

- Allport, G.W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- Ellison, C.G. and Powers, D.A. (1994). The contact hypothesis and racial attitudes among black Americans. Social Science Quarterly, 75(2), pp. 385–400.

- Espenshade, T.J. and Hempstead, K. (1996). Contemporary American attitudes toward US immigration. International Migration Review, 30(2), pp. 535–570.

- Fetzer, J.S. (2000). Economic self-interest or cultural marginality? Anti-immigration sentiment and nativist political movements in France, Germany and the USA. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 26(1), pp. 5–23.

- Hjerm, M. (2001). Education, xenophobia and nationalism: a comparative analysis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(1), pp. 37–60.

- Parliament of Georgia. (2014). Law of Georgia on the Legal Status of Aliens and Stateless Persons. Available at: <https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/2278806> [Accessed 31 Jan. 2018].

- Petraia, L. (2017). Who was in and who was out in Tbilisi’s far-right March of Georgians [Analysis]. OC Media, [online]. Available at: <http://oc-media.org/who-was-in-and-who-was-out-in-tbilisis-far-right-march-of-georgiansanalysis/> [Accessed 31 Jan. 2018].

- Pettigrew, T.F. and Tropp, L.R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), pp. 751–783.

- Raijman, R., Semyonov, M. and Schmidt, P. (2003). Do foreigners deserve rights? Determinants of public views towards foreigners in Germany and Israel. European Sociological Review, 19(4), pp. 379–392.

- Rodriguez-Garcia, D. (2010). Beyond Assimilation and Multiculturalism: A Critical Review of the debate on Managing Diversity. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 11(3), pp. 251–271.

- State Commission on Migration Issues. (2015). Migration Strategy of Georgia 2016–2020. Available at: <http://migration.commission.ge/files/migration_strategy_2016-2020_eng_final_-_amended.pdf> [Accessed 31 Jan. 2018].

- State Commission on Migration Issues. (2017). 2017 Migration Profile of Georgia. Available at: <http://migration.commission.ge/files/migration_profile_2017_eng__final_.pdf> [Accessed 19 Mar. 2018].

- Verbeck, G., Scheepers, P. and Felling, A. (2002). Attitudes and behavioural intentions towards ethnic minorities: An empirical test of several theoretical explanations for the Dutch case, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 28(2), pp. 197–219.

About the Authors

Dr. Natia Mestvirishvili is a researcher at the analytical unit of the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), ENIGMMA project and a Non-resident Senior Fellow at CRRC Georgia. Natia earned a PhD in psychology from Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. She holds an M.Sc. in Social Research from the University of Edinburgh (UK) and an M.A. in Global Development and Social Justice from St. John’s University (US). Natia’s research interests involve identity and value changes and migrants’ integration.

Dr. Maia Mestvirishvili is Associate Professor at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences. From 2006–2011, she received research and academic scholarships at the Universities of Columbia (USA), Berkeley (USA) and Leuven (Belgium). She also received research grants from the Academic Swiss Caucasus Net (ASCN) and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). Her major research interests are social identities, stigma and coping, moral judgement and religious attitudes. Dr. Mestvirishvili is the author of several international conference papers and journal articles.

Population’s Attitudes Towards Georgia’s Foreign Policy Choices in Times of Uncertainty

By David Sichinava

Abstract

This article explores key characteristics of people’s attitudes towards Georgia’s foreign policy choices and the factors that most likely predict these attitudes. While the support for NATO and/or European Union membership clearly represents a pro-Western orientation, the support for membership in the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union also needs to be analyzed. In addition to discussing the factors that might explain people’s support, the article looks at how the population of Georgia feels about the country’s hypothetical neutral status.

Introduction

The idea of Georgia becoming a member of the European Union and NATO has been almost unanimously endorsed by key Georgian political parties and by the national government. Meanwhile, recent opinion polls indicate growing neutral or skeptical sentiments of the population towards the country’s pro-Western aspirations. Based on the data from the 2017 wave of the CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer survey, this article discusses the population’s attitudes towards Georgia’s foreign policy choices and the factors that are most likely behind them.

Georgia’s foreign policy orientation remains at the very heart of the policy debate in Georgia. However, this issue is less salient for ordinary people. Polls show that Georgia’s potential membership in NATO or in the European Union is not the issue that people worry about most, while unemployment and poverty are almost exclusively named as the most important issues the country faces1. Nevertheless, the majority of the population of Georgia has keenly supported the country’s leanings towards the West.2 However, little is known about how specific groups of the population feel about the country’s foreign policy orientation or about the factors that statistically predict people’s foreign policy preferences in Georgia.

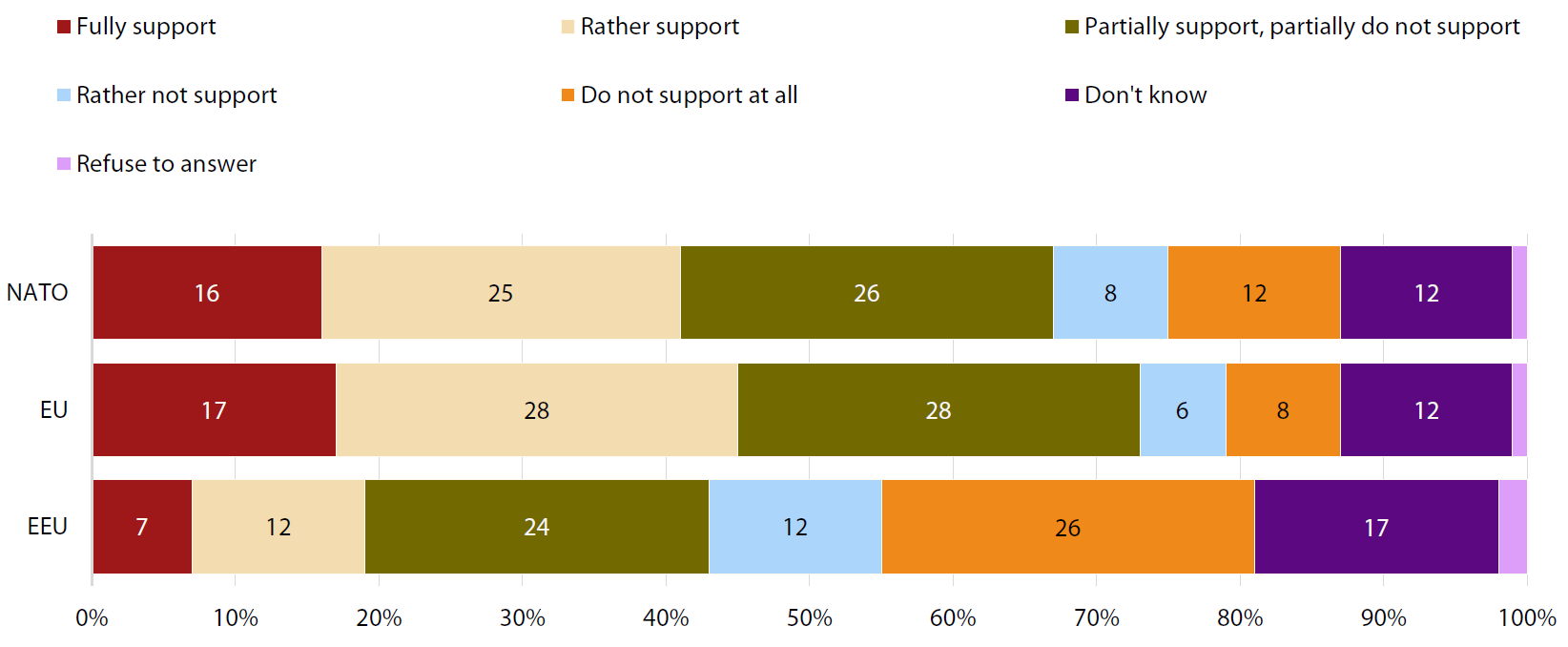

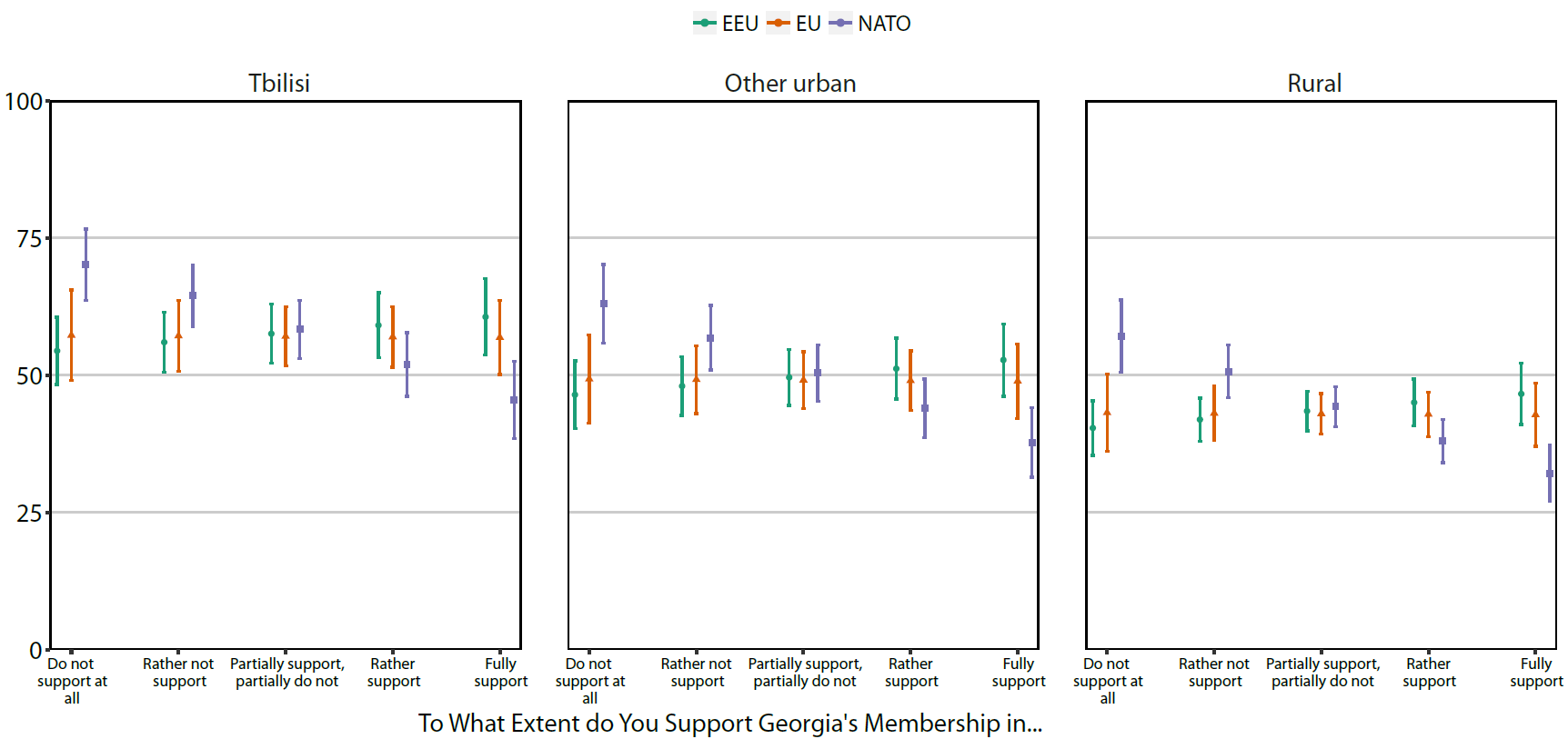

How Do People Feel About Political Unions?

The population remains positively disposed towards the country’s Western-oriented foreign policy (see Figure 1 on p. 9). While 41% would support Georgia’s NATO membership, this share is twice the share of those who are against it. Membership in the European Union is supported by almost half of the population, while it is opposed by only 14%. A much smaller share is keen to support the country’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union led by the Russian Federation—only one fifth, while twice as many oppose the idea.

Over time, however, people in Georgia have become less supportive of the country’s membership in any union. The proportion of those who back the country’s NATO membership declined from 70% in 2010 to a mere 41% in 2017. While 69% supported the idea of the country becoming a member of the European Union in 2011, only 45% felt so in 2017. Importantly, the decline in support has been accompanied by an increasing proportion of those who partially support, partially do not support, or do not know how to answer the respective question.

People reflect differently about potential gains and losses when supporting or opposing membership in each of the unions. Those who back the NATO membership bid consider Georgia’s security and territorial integrity:3 approximately one-third of NATO supporters believe that the membership will protect the country from foreign threats, while approximately one-fifth think that it will increase Georgia’s chances of restoring its territorial integrity.

Economic considerations resurface in regard to the reasons why people in Georgia support the country’s hypothetical membership in the European Union or the Eurasian Economic Union. Almost half of those who would support Georgia’s EU membership hope that it will help improve the economic conditions of the population.4 The same hope is reported by 40% of EEU supporters.5 In both cases, the second most important reason for support of Georgia’s membership in the EU or EEU is the belief that it would strengthen the country’s ties, respectively, with the West or with Russia.

What Factors Predict Support for Membership in Political Unions?

Studies from elsewhere in the broader post-communist space argue that the attitudes towards integration in the European Union are shaped by the peculiarities of post-Communist transition and its impact on the economy (Tucker et al, 2002). Among other factors, the expected economic benefits from EU membership often drive people towards supporting the cause (Hobolt & de Vries, 2016; Boomgaarden et al, 2011). At the same time, positive attitudes towards democracy, foreigners, or immigrants are also good predictors of pro-Western attitudes (Cichowski, 2000; Garry & Tilley, 2009). Below I evaluate whether some or all of these factors statistically predict attitudes towards Georgia’s membership in these political unions6.

As the regression models show, the population’s demographic and socio-economic characteristics predict their feelings towards the European Union, NATO, and the Eurasian Economic Union to some extent. Not surprisingly, younger people are more prone to support the country’s membership in the Western-led political organizations than those who are older. The latter are more likely to oppose the cause and feel positive towards the hypothetical Eurasian path.

The analysis also shows that Tbilisi residents are twice more likely than rural residents to oppose the country’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union. They are also among the staunchest supporters of Georgia’s EU membership. The ethnic minority population7 is somewhat reluctant to support the idea of Georgia becoming a part of the European Union and NATO, while their ethnic Georgian peers are much more enthusiastic about such opportunities. The ethnic minority population, on the other hand, is more supportive of EEU membership than ethnic Georgians are.

Higher household income is associated with people’s more positive feelings towards the West. Contrary to expectation, when controlling for other factors, people’s education does not predict attitudes towards Georgia’s foreign policy choices.

In regard to values, people’s negative attitudes towards immigrants stand out as a good predictor of their opposition to integrating into the Western-led blocs. The way people perceive domestic politics and the government are also good predictors of their attitudes towards foreign policy choices. Those who believe that domestic politics in Georgia are developing in the right direction or are not changing are less likely to oppose EU and NATO membership and to support integration in the Eurasian Economic Union. The supporters of EEU membership are those who report that the country’s domestic politics are developing in the wrong direction.

Foreign policy preferences differ across groups with different perceptions about the role of the government. Those who believe that the government should be the people’s employee and be controlled by the citizens are twice more likely to support than to oppose EU membership. They are also more prone to oppose Georgia’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union. On the other hand, those who see the government as a parent who takes care of people as if they were children are slightly less likely to support the country’s membership both in the European Union and NATO. Interestingly, attitudes towards the role of the government are highly correlated with education and settlement type. People living in rural settlements are more likely to have paternalistic attitudes, as do those having lower levels of education.

To Be or Not to Be Neutral?

The ideas about Georgia’s neutral status sometimes make it into the country’s political discourse. Certain politicians8 and the representatives of pro-Russian9 civil society organizations10 argue that neutrality is the path leading to the security and the development of the country. The neutral or “non-aligned” status of Georgia is, however, unacceptable for the mainstream Georgian politicians and analysts11, and the public seems to be divided over the issue.

Approximately half of the people in Georgia would prefer the country’s neutral status over its membership in any union. A closer examination12 of the CB data suggests that lack of support of Georgia’s NATO membership is a good predictor of people’s belief that neutrality is the best choice for the country (see Figure 2 on p. 9). Interestingly, support for Georgia’s membership in either the EU or the EEU does not seem to influence attitudes towards the country’s neutrality.

Factors other than the support for Georgia’s NATO membership are associated with less pronounced variations in how people feel about their country’s neutrality. The way people perceive tensions between the West and Russia predicts their feelings towards the country’s neutrality. Those who believe that these tensions are detrimental to Georgia are slightly more likely to think that Georgia should embrace neutrality. In the same vein, older people and the ethnic minority population are also more prone to agree that neutrality could resolve Georgia’s conflicts and help improve the country’s security.

To sum up, a large share of the population of Georgia prefers neutrality over the country’s alignment with a political union. The lack of support for NATO membership well predicts such a position. Interestingly, attitudes towards neutrality do not vary significantly by major demographic characteristics.

Concluding Remarks

In general, the population of Georgia supports the country’s official foreign policy priorities, although the results of the 2017 wave of the Caucasus Barometer survey show growing ambivalence. While unemployment and poverty are haunting people in Georgia, they hope that Western prospects would bring better livelihood and improved security. Georgia still has to wait to harvest fruits of the close cooperation with the West. It might be tempting to ascribe the growing ambivalence to the rising Russian influence—however, this would be an exaggeration.

About the Author

Dr. David Sichinava is a senior policy analyst at CRRC-Georgia and assistant professor of human geography at Tbilisi State University. David holds his undergraduate and graduate degrees in Human Geography from Tbilisi State University (TSU). In the fall semester 2016, he was a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at the Institute of Behavioral Sciences of the University of Colorado Boulder. David’s research interests are focused on political geography, urban theory, election modeling and GIS applications in social sciences.

Notes

1 <http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/IMPISS1/>

2 <http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16868>

3 <http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb2017ge/NATOSUPW/>

4 <http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb2017ge/EUSUPWHY/>

5 <http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb2017ge/EEUSUPW/>

6 The probabilities presented in this section are based on regression models predicting the support of Georgia’s membership in the European Union, NATO and the Eurasian Economic Union. Predictors (the independent variables) are respondents’ demographic characteristics (gender, age, settlement type, household income, reported ethnicity, and highest level of education achieved) and attitudes towards immigrants, assessments of the direction of domestic politics, the role of the government and so forth. Detailed information and replication data can be obtained at <https://github.com/crrcgeorgia/fpc_geo>

7 A variable on self-reported ethnicity was used to classify ethnic majority (Georgians) and ethnic minority (all other ethnicities) groups.

8 <http://netgazeti.ge/news/134040/>

9 <https://jamestown.org/program/pro-russian-forces-in-georgia-demand-neutral-status-for-country/>

10 <https://sputnik-georgia.com/georgia/20160325/230800736/saqartvelo-samxedro-neitralitetis-gzaze.html>

11 <http://netgazeti.ge/news/134192/>

12 The probabilities presented in this section have been computed based on a regression model that predicts the support of the statement “Georgia’s neutrality could help resolve conflicts and improve Georgia’s security.” Potential predictors (i.e., the independent variables, whose influence was tested in the model) are demographic characteristics (gender, age, settlement type, reported ethnicity, and highest level of education achieved); attitudes towards the potential effects of tensions between foreign countries on Georgia, and the support of Georgia’s membership in the EU, NATO, and the Eurasian Economic Union.

Bibliography

- Tucker, J. A., Pacek, A. C., & Berinsky, A. J. (2002). Transitional winners and losers: Attitudes toward EU membership in post-communist countries. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 557–571.

- Hobolt, S. B., & de Vries, C. E. (2016). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 413–432.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., Schuck, A. R., Elenbaas, M., & De Vreese, C. H. (2011). Mapping EU attitudes: Conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support. European Union Politics, 12(2), 241–266.

- Cichowski, R. A. (2000). Western dreams, eastern realities: Support for the European Union in Central and Eastern Europe. Comparative political studies, 33(10), 1243–1278.

- Garry, J., & Tilley, J. (2009). The macroeconomic factors conditioning the impact of identity on attitudes towards the EU. European Union Politics, 10(3), 361–379.

Figure 1: To What Extent Would You Support Georgia’s Membership in ...? (%)

Figure 2: Agree That Georgia Should Be Neutral Predicted Probabilities With 95% Confidence Intervals

Inconsistent (Dis)Trust in Polls in Georgia: Wrong Expectations?

By Tinatin Zurabishvili

Abstract

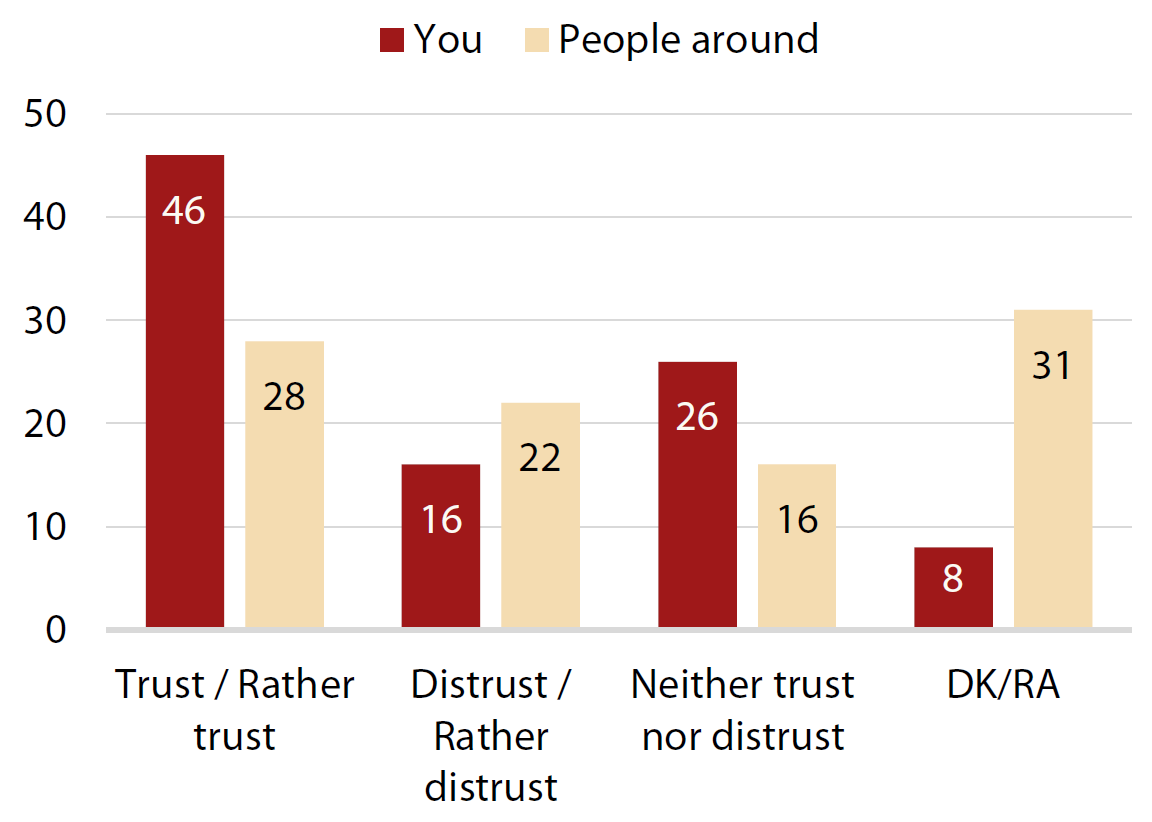

In CB 2017, the CRRC continued to measure the population’s trust in public opinion polls’ results in Georgia. While almost half of the population reported trusting poll results themselves, a much weaker belief was recorded that ‘people around’ trust the results of public opinion polls conducted in Georgia. Only a quarter of the population reported trusting public opinion poll results and, at the same time, believed that people around them also trusted them. Three quarters, on the other hand, agreed that polls help all of us obtain better knowledge about the society we live in. This paper presents some of the inconsistences in the attitudes towards polls in Georgia, confirming one of the major findings based on the 2015 data: there is so far little certainty in the Georgian society about public opinion polls.

Introduction

Any society challenges the trustworthiness of public opinion polls at some point(s) of its development. Journalists, policymakers and academics discuss the issue, expressing varying degrees of skepticism. ‘Failures’ of polls to predict events such as Brexit—or the outcome of any regular election, for that matter—fuel this skepticism and may lead to the development of sophisticated conspiracy theories. “Can we still trust opinion polls after 2015, Brexit and Trump?”—asks the Guardian (Travis 2017). “Can we trust the polls? It all depends,”—the Brookings Institution tries to reason (Traugott 2003), while Levada Center’s relatively earlier publication describes a crisis of understanding “reality,” largely caused by a society’s limited possibilities to understand it (Gudkov 2016).

Societies with a less developed ‘survey culture’ (to which all post-Soviet societies belong) find it more difficult to trust opinion polls. Georgia is a rather turbulent example in this respect. Questions about the population’s trust in public opinion polls were first asked in the 2015 wave of the CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer survey (CB) and discussed in the 85th issue of the Caucasus Analytical Digest (Zurabishvili 2016). The issue of polls’ trustworthiness is still an emotionally debated issue in Georgia; thus, the CRRC has decided to collect the same data in the course of the 2017 CB wave as well. In this article, new findings are presented and compared to the earlier results.

Reported Trust in Poll Results: ‘Me’ vs. ‘People Around’

Almost half (46%) of the population of Georgia reported trusting the results of public opinion polls conducted in the country, according to CB 2017, with only 4% saying they do not know anything about the polls. The answers are, however, affected to a certain degree by social desirability bias: when asked, “[W]ould you say that most of the people around you trust or distrust the results of public opinion polls conducted in Georgia?”, only 28% answered positively (Figure 1).1

Figure 1: Would you say that you / most of the people around you trust or distrust the poll results? (%)

Various factors may affect people’s answers to these two questions and explain the difference. As it has been widely and convincingly argued by the theorists of public opinion, people often feel more confident—and more sincere—when they speak about their perceptions of others’ opinion than when they report their own opinion on sensitive issues, or when they frame their opinion as a ‘generally widespread’ one. In this light, the actual level of trust in poll results in Georgia should be believed to be somewhere between the two trust figures of 46% and 28%, and this estimate is in line with the 2015 findings of a rather modest level of trust.

It might be due to the changes in the wording of the question about personal trust in public opinion poll results,2 but in the 2017 data, the correlations between the answers to this question and reported trust in major social and political institutions are much weaker. The strength of correlation is relatively stronger (although rather weak in absolute terms) in cases of the educational system (Spearman correlation coefficient being -.139), local government (-.137), police (-.126) and the president (-.120), i.e., institutions that have quite different roles and functions, as well as background and image in the society. Thus, it would be very hard to argue that the nature of people’s trust in the results of public opinion polls in Georgia is more or less similar to the nature of trust in major social and political institutions. It is, however, quite clear that trust—or distrust— in public opinion polls is not a consistent and straightforward phenomenon.

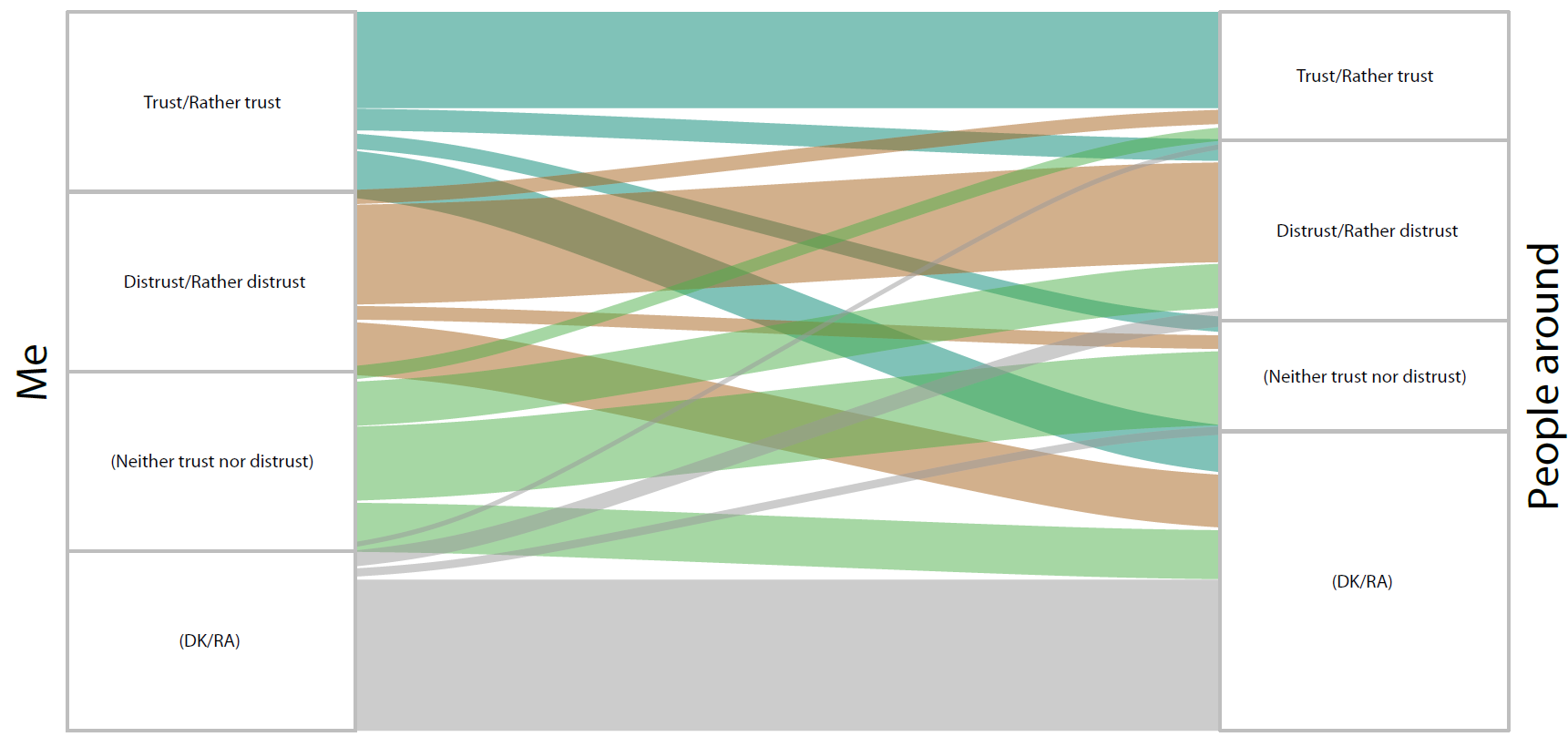

Paradoxes of (Dis)Trust

Although there is a rather high correlation between the answers to the questions about personal vs. others’ trust in poll results (Spearman correlation coefficient is .371), approximately half of the population assessed other people’s (dis)trust in poll results in Georgia differently than his/her own (dis)trust (Figure 2). For example, of those who reported trusting the poll results themselves, 53% believed the same to be the case for people around them; 26% reported that they did not know about others, while the rest believed that the others either did not trust poll results (12%) or neither trusted nor distrusted them (9%).

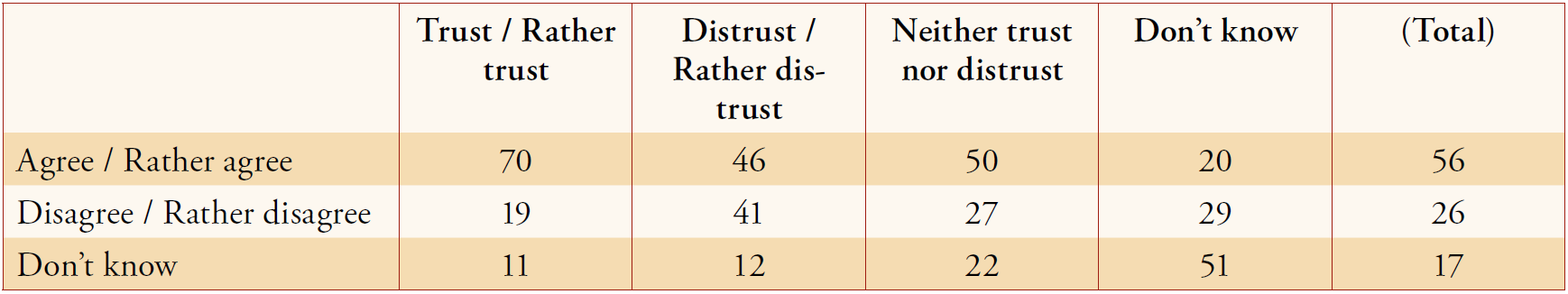

The inconsistencies that can be seen in Figure 2 are not the only ones that are observed when looking closely at the CB findings. 83% of the population reporting distrust of the results of public opinion polls conducted in Georgia believe at the same time that the government should consider these results when making political decisions. The respective share is 85% among those who neither trust nor distrust poll results. To continue, 59% of those who distrust poll results also say that the polls help all of us get better knowledge about the society we live in. In addition, 74% of those disagreeing with the opinion that polls help all of us obtain better knowledge about the society we live in claim that the government should consider these results when making political decisions.

The low level of trust is in fact surprising when looking at the assessments of specific qualities of polls by the population of Georgia. An impressive majority (76%) agrees with the opinion that “Public opinion polls help all of us get better knowledge about the society we live in,” with almost no variation by major demographic characteristics. An even larger and thus even more impressive share (86%) agrees that “The government should consider the results of public opinion polls while making political decisions,” with those living in the capital and those with higher than secondary education being more convinced in this compared to the rest of the population. With only approximately one-third of the population agreeing with the statement, “Public opinion polls can only work well in developed democratic countries, but not in countries such as Georgia”—thus with a majority believing that Georgia is no exception to the polls’ potential best practices—it would seem that public opinion polls should be rather appreciated in the country.

Figure 2: [W]ould you say that you trust or distrust the results of public opinion polls conducted in our country? By [W]ould you say that most of the people around you trust or distrust the results of public opinion polls conducted in our country? (%)

However, this is not the case. Approximately two thirds (64%) agree with the statement, “Ordinary people trust public opinion poll results only when they like the results,” and 78% believe that politicians trust these results only when they are favorable for them or for their party. These findings suggest that people are mostly able to see the biased attitudes of ‘the others,’ be it politicians or ‘people’ in general, but to what extent are they biased themselves, and if they are, would they admit their own bias?

Slightly over the half of the population of Georgia reports that they think they understand quite well how public opinion polls are conducted. While it would be impossible to test the reliability of this self-assessment, there is an interesting tendency showing that those who believe they have knowledge of survey practices report trusting polls more often (Table 1).

Overall, 24% of the population reported trusting public opinion poll results in Georgia and at the same time believed people around them to trust them. Interestingly, these people can be found in villages rather than in the capital. Quite counterintuitively, people with different levels of education are evenly represented in this group. For the rest, though, this relatively small group tends to be more consistent in its position. Compared to the rest of the population, a higher share of people who reported trusting public opinion poll results and at the same time believed people around them to trust them said that they understand quite well how public opinion polls are conducted, and 97% of them also believed that public opinion polls help all of us get better knowledge of the society we live in.

Wrong Expectations?

Since public opinion, by its nature, is not and should not be expected to be straightforward (Lippmann 1997), the polls are not here to provide straightforward conclusions or to directly predict an outcome of elections. Too often, the polls—their quality, reliability, and even the very fact of whether they are needed or not in a society— are judged without understanding their nature, and thus, they will be ‘wrong again’ (Lipsey 2017) if judged so. It takes certain expertise, as well as at least minimal specialized education, to be able to reasonably judge the reliability of public opinion polls—a precondition that journalists and policymakers in Georgia mostly lack. As a result, they often create ‘straightforward’ expectations among their audience—expectations that the polls cannot meet. When judging the polls from the point of view of whether they have been ‘right or wrong’ in predicting a certain social event, the ‘opinion makers’ often completely miss the point—that of trying to understand the public opinion.

Table 1: [W]ould you say that you trust or distrust the results of public opinion polls conducted in our country? By “I think I understand quite well how public opinion polls are conducted” (%)

Note

1 A 10-point scale and respective Show Card were used in 2015. In 2017, the answer options were simplified: a 3-point scale, and no show card was used. Thus, the findings are not directly comparable over time. Bearing the existing differences in mind, however, broadly speaking, there are few differences in the level of trust between 2015 and 2017.

Bibliography

- Gudkov, L. [Гудков, Л.] (2016). Кризис понимания «реальности». Вестник общественного мнения, № 3–4 (122), p. 29–51.

- Lippmann, W. (1997 [1922]). Public Opinion. New York: Free Press Paperbacks.

- Lipsey, D. (2017). Polling’s Dirty Little Secret: Why polls have been wrong before and will be again. The Guardian [online]. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/apr/25/dirty-little-secret-opinionpolls-general-election-why-wrong> [Accessed 9 Feb. 2018].

- Travis, A. (2017). Can We Still Trust Opinion Polls after 2015, Brexit and Trump? The Guardian [online]. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/may/08/opinion-polls-general-election> [Accessed 5 Feb. 2018].

- Traugott, M.W. (2003). Can We Trust the Polls?: It All Depends. The Brookings Institution [online] Available at: <https://www.brookings.edu/articles/can-we-trust-the-polls-it-all-depends/> [Accessed 5 Feb. 2018].

- Zurabishvili, T. (2016). Public Opinion on Public Opinion: How does the population of Georgia see public opinion polls? Caucasus Analytical Digest No. 85, pp. 2–5. Available at: <http://www.css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/CAD85.pdf> (Assessed 9 Feb. 2018).

About the Author

Tinatin Zurabishvili holds a PhD in Sociology of Journalism from Moscow M. Lomonosov State University. From 1994 to 1999, Tinatin worked for the Yuri Levada Analytical Center in Moscow (VTsIOM at the time). After returning to Georgia in 1999, she taught various courses in sociology, particularly focusing on research methodology, for BA and MA programs at Telavi State University and the Tbilisi State University Center for Social Sciences. From 2001 to 2003, she was a Civic Education Project Local Faculty Fellow; from 2010 to 2012, she was a professor at the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs (GIPA). In 2007, she joined the Caucasus Research Resource Centers (CRRC) as the Caucasus Barometer survey regional coordinator. Since 2012, she has worked as CRRC-Georgia’s research director. Her research interests are focused on post-Soviet transformation, sociology of migration, media studies, and social research methodology.

Thumbnail external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Frank Miller/Flickr. external page(CC BY-SA 2.0)call_made

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.