Burden-sharing in NATO: The Trump Effect Won´t Last

13 Dec 2017

By Peter Viggo Jakobsen and Jens Ringsmose for Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageNorwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI)call_made on 29 November 2017.

Introduction

The Trump Administration has adopted a more confrontational and transactional approach to burden-sharing in NATO. It has threatened to “moderate” its commitment to the Alliance unless the European members increase their defence spending (US Mission to NATO 2017), and contribute more to out-of-area operations. Since President Trump entered the office, European defence spending has risen at a quicker pace, and the nature of the defence debate in Europe has changed. The Europeans are no longer debating whether they need to increase their spending; the questions discussed are how fast and how much. Is this evidence of a “Trump effect”, and will it last? This is the question addressed in this policy brief. Because it is hard to predict the future, we adopt an historical perspective.

Two structural factors have conditioned the burden-sharing games since the creation of the Alliance in 1949:

(1) External threats giving the Americans and the Europeans a shared interest in establishing and maintaining the Alliance.

(2) The asymmetric power relations between the United States and the Europeans, giving all European allies except France and Great Britain, who needed their own military capabilities to underpin their great power ambitions, a strong incentive to free-ride and spend less on defence.

These factors set the stage for a transatlantic burden-sharing game, which had the Americans constantly pressuring its European allies to do more, and the Europeans responding by doing what they deemed necessary to keep the Americans in Europe – but little more. The European willingness to contribute to the Alliance was primarily driven by American pressure and the Soviet threat. It was about keeping the Russians out and the Americans in as NATO’s first Secretary-General Lord Ismay once put it. A combination of shared interests and the liberal values mentioned in the Washington Treaty has prevented this burden-sharing game from tearing the Alliance apart until now, and it is our conclusion that they will continue to do so in the foreseeable future. The Trump effect is therefore limited – if it exists at all.

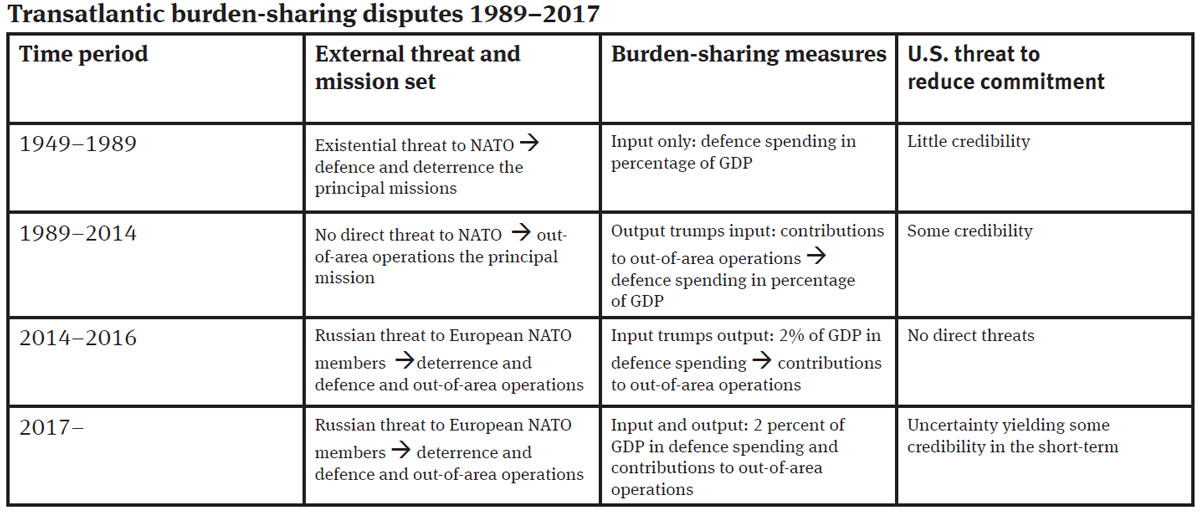

In the analysis below, we show how different levels of external threats have affected NATO’s mission sets, the burden-sharing indicators adopted by the Alliance to ensure that all did their fair share, and the credibility of the American threats to reduce their commitment unless the Europeans did more. The analysis reveals a continuity corroborating our claim that the Trump Administration will be unable to make a major difference to European defence spending.

The Cold War: Burden-sharing as input

NATO was a response to the Cold War. Concern that the Western European countries would be unable to deter and, if need be, defeat a Soviet attack induced American decision-makers to deploy a large number of troops to Europe on a permanent basis. But already in 1949, Washington realized that its commitment to defend Europe would give the European NATO members an incentive to spend less on defence. They therefore inserted Article 3 in the Washington Treaty to prevent this. The emphasis of Article 3 on individual capacity and self-help, Secretary of State Dean Acheson told Congress during the NATO ratification hearings in 1949, was to “ensure that nobody is getting a meal ticket from anybody else so far as their capacity to resist is concerned” (cited in Ringsmose 2010, 321).

Defence spending in proportion to GDP was the principal indicator employed to ensure that “nobody got a free meal ticket”. Yet the choice of this indicator set the stage for continuous transatlantic conflict, because the United States spent far more on defence in proportion to GDP than the Europeans.

Asymmetric defence spending led to increased frustration in the United States as the Europeans recovered economically from the destruction of World War II. In the 1960s and 1970s, U.S. Senator Mansfield introduced a series of amendments in Congress proposing that the United States should reduce the number of troops permanently stationed in Europe, in order to induce the Europeans to do more themselves. These threats to withdraw a substantial number of U.S. forces had little credibility, because the resolutions failed to pass. However, the congressional pressure did help U.S. Administrations from the 1960s onwards achieve some success with a quid-pro-quo approach promising to maintain their military commitment in Europe in return for increased European defence spending. Yet, the Europeans never met the U.S. demands fully, realizing that the U.S. had no interest in leaving.

The Post-Cold War era: Output trumps input

The disappearance of the Soviet threat transformed NATO’s strategic environment and the nature of the transatlantic burden-sharing game. NATO’s principal mission shifted from deterrence and defence to out-of-area operations. While the Cold War input burden-sharing indicator remained in use, the United States introduced a set of additional measures to pressure the Europeans to transform forces to more deployable ones. The Defence Capabilities Initiative from 1999, the Prague Capabilities Commitment agreed at NATO’s summit in Prague in November 2002, and the NATO Response Force launched that same year, all served this purpose (Rynning 2005: 102–140).

American threats to reduce their commitment to NATO also played an important role in the new burden-sharing game. “Out of area or out of business”, the slogan popularized by U.S. Senator Lugar (1993), captured the new dynamics. These threats induced the Europeans to accept greater use of force and make larger force contributions than they would have done otherwise (Jakobsen 2014). The credibility of U.S. threats to withdraw was higher than it had been during the Cold War because Russia no longer posed an existential threat to NATO.

The introduction of new output indicators culminated at the Istanbul Summit in June 2004 with the endorsement of the so-called usability targets. The agreed aim for national land forces was that 40% had to be structured, prepared and equipped for deployed operations, and 8% had to be undertaking or planned for sustained operations. The 40/8 target was adopted at the Riga Summit in 2006, and it was subsequently revised upwards to 50/10 (Ringsmose and Rynning 2009: 23–24).

The Riga Summit also dusted off the traditional GDP input measure, as the members committed themselves to work towards spending 2% of GDP on defence. The United States pressured its European partners to make this commitment to stem the fall in European defence spending that had occurred since the end of the Cold War (Ek 2007).

In addition to these formal measures, an informal one – the willingness to put one’s troops into harm’s way (risk-sharing) – emerged as a key burden-sharing measure as NATO became involved in combat missions. To give an example, Denmark’s willingness to do high-risk combat missions in Southern Afghanistan, resulting in 43 fatalities, and its contribution in Libya earned it a lot of praise from the United States (Jakobsen 2016: 201). By contrast, Germany, the third largest force contributor to NATO’s Afghanistan mission (5.000 personnel), was heavily criticised for its unwillingness to do combat in the South, and for its unwillingness to contribute to NATO’s Libya mission.

The Danish example illustrates how the Europeans exploited the new set of formal and informal burden-sharing measures to “keep the Americans in” without meeting all the U.S. burden-sharing demands. On the one hand, the Europeans made their forces more deployable and increased their contributions to out-of-area operations. On the other, they refrained from spending more on defence.

The Post-Crimea era (2014–2016): Input trumps Output

This changed when Russia’s annexation of the Crimea in 2014 turned the strategic environment in Europe upside down. Suddenly, the military threat to NATO’s European territory had reappeared, and this put NATO Cold War missions – territorial defence and deterrence – back in the driver’s seat. Although out-of-areas missions did not vanish from NATO’s radar completely, they now played second fiddle.

The United States played a key role in shaping the Alliance’s response to the rising Russian threat. The Obama Administration sent aircrafts and soldiers to Eastern Europe, increased U.S. participation in NATO exercises and took steps to enable the swift deployment of major U.S. reinforcements in Eastern Europe. The U.S. was also the key architect behind the Readiness Action Plan adopted at the 2014 Wales Summit.

The rise of the Russian threat facilitated the American efforts to pressure its European allies to spend more on defence. Frustrated with European free-riding during the Libya campaign, the Obama Administration had pushed hard since 2011. These efforts made little progress prior to the Russian annexation of the Crimea. After Crimea, the Europeans promised at the Wales Summit to “halt any decline in defence expenditure” and to “aim to move towards the 2% (GDP) guideline within a decade”. The European members also committed to meet another existing NATO target to devote 20% of defence expenditures to military procurement and research and development (NATO 2014). Input measures had reappeared as trumps in the transatlantic burden-sharing game.

Yet, the Obama Administration’s attempts to pressure its allies to spend more had limited success. While the collective decline in European defence expenditure was halted, there was little positive movement towards the 2% target as the Europeans’ collective defence spending remained constant at 1.45% of GDP between 2014 and 2016 (NATO 2017: 8). Two factors accounted for this: diverging threat perceptions of Russia, and the strong American response to Crimea. While the Russian behaviour in the Ukraine scared the European NATO members bordering Russia into spending more on defence, the majority of the European members did not view Russia as a direct military threat to the their national security (Jakobsen and Ringsmose 2018). Paradoxically, the Obama Administration’s strong reaction to Crimea reinforced this perception, as the American show of force removed the need for the Europeans to do more themselves.

The Trump era (2017–): Spend 2% and contribute more out-of-area or NATO dies

While the threat environment and NATO’s mission set remained unaltered, the election of Mr Trump changed the dynamics of the burden-sharing game. Before his election, Trump called the Alliance “obsolete” and said that he only would defend allies spending 2% of GDP on defence. These threats did not go away after his election. His Secretary of Defense Mattis made clear in February 2017 that the United States would “moderate” its commitment to the Alliance unless the allies spending too little made clear progress towards honouring the commitments made at the Wales Summit. Secretary of State Tillerson added another output measure the following month demanding greater European assistance in the fight against terrorism (U.S. Department of State 2017). Thus, the Trump Administration not only demanded more input, it also wanted more output, and it used harsher rhetoric and threatened more drastic measures if the Europeans did not comply. While previous administrations had made NATO’s longer-term survival conditional upon greater European burden-sharing, a U.S. Administration had never before made the defence of an ally facing an immediate threat contingent upon its defence spending.

European diplomats have criticised the Trump Administration severely for its unfair and inaccurate portrayal of their NATO contributions. Yet defence spending is on the rise in most the European member states. 23 of America’s 27 European allies (+ Canada) will increase their spending in 2017, and their combined spending is projected to increase by 4.3% (NATO 2017:2).

Conclusion

This policy brief has analysed the transatlantic burden-sharing games played in NATO since 1949 as a function of the three factors presented in the table below. The existential threat posed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War led to a burden-sharing focus on the primary defence and deterrence mission. Defence spending measured in proportion to GDP emerged as the principal measure of allied burden-sharing. The existential nature of the Soviet threat prevented burden-sharing disputes from getting out of hand. The disappearance of the existential threat paved the way for making out-of-area operations NATO’s primary mission. The increased credibility of the American threats to leave the Alliance induced the Europeans to increase their out-of-area contributions. However, they kept decreasing their defence spending. The burden-sharing disputes related to out-of-area operations were more intense than the disputes related to defence spending during the Cold War, because the overlap between U.S. and European interests fell, as these operations moved further away from Europe.

The rise of the Russian threat changed the game again. The strong pressure from the Obama Administration combined with rising threats to the East induced the Europeans to stop cutting their defence spending. At the same time, the strong leadership displayed by the Obama Administration reduced the pressure on the European members not bordering Russia to increase their defence spending.

The Trump Administration increased the American pressure on the Europeans by threatening to refrain from defending allies that do not take measurable steps to meet the 2% target and contribute more to out-of-area operations. Yet, the credibility of this threat is bound to decrease over time because of the obvious disconnect between words and deeds.

The Trump Administration’s continuation of the military leadership initiated by the Obama Administration with respect to deterring Russia signals a strong American interest in the Alliance that will remain as long as American decision-makers define the United States as a global power with global interests. NATO remains an indispensable part of the United States global power projection infrastructure. An American withdrawal from NATO would spell an end to the American alliance system in Asia, because Japan, South Korea and Taiwan would lose faith in the American willingness to support them in a future confrontation with China. Nothing in our analysis suggests that the Trump Administration’s more confrontational and transactional approach will change this. The American interest in keeping NATO alive in support of its own grand strategy reduces the credibility of the Trump threat to terminate the Alliance.

This gives the Europeans spending less than 2% room to continue “free-riding” in the future. They will continue to do so and the Americans will continue to complain about it. But the Americans will not leave because the Europeans will do enough to “keep the Americans in”. Therefore, the Trump effect, if it exists at all, seems destined to be temporary.

References

Ek, Carl (2007) NATO’s Prague Capabilities Commitment, CRS Report for Congress, RS21659, January 24.

Jakobsen, Peter Viggo (2014) “The Indispensable Enabler: NATO’s Strategic Value in High-Intensity

Operations Is Far Greater Than You Think.” In Liselotte Odgaard (ed.) Strategy in NATO: Preparing for an imperfect world (New York: Palgrave Macmillan): 59-74.

Jakobsen, Peter Viggo (2016) “The Danish Libya Campaign: Out in Front in Pursuit of Pride, Praise, and Position,” in Dag Henriksen and Ann Karin Larssen (eds.) Political Rationale and International Consequences of the War in Libya (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 192-208.

Jakobsen, Peter Viggo and Jens Ringsmose (forthcoming 2018) Victim of its own success: How NATO’s difficulties are caused by the absence of a unifying existential threat, Journal of Transatlantic Studies.

Lamothe, Dan and Michael Birnbaum (2017) Defense Secretary Mattis issues new ultimatum to NATO allies on defense spending, Washington Post, 15 February.

Lugar, Richard. D. (1993) NATO: Out of Area or Out of Business: A Call for U.S. Leadership to Revive and Redefine the Alliance. Speech to the Overseas Writers’ Club, Washington D.C., 24 June.

U.S. Mission to NATO (2017) Intervention by U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis Session One of the North Atlantic Council NATO Defense Ministerial, 15 February.

NATO (2014) Wales Summit Declaration, 5 September.

NATO (2017) Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2010-2017), 29 June.

Ringsmose, Jens (2010) “NATO Burden-Sharing Redux: Continuity and Change after the Cold War,” Contemporary Security Policy, 31:2: 319-338.

Ringsmose, Jens and Rynning, Sten (2009) ‘Come Home NATO? The Atlantic Alliance’s New Strategic Concept’, DIIS Report 2009:4 (Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies).

Rynning, Sten (2005) NATO Renewed: The Power and Purpose of Transatlantic Cooperation (New York: Palgrave).

US Department of State (2017) NATO Foreign Ministerial Intervention Remarks, 31 March.

About the Authors

Peter Viggo Jakobsen is Associate Professor in the Department of Strategy at the Royal Danish Defence College and Professor (part time) at Center for War Studies, University of Southern Denmark.

Jens Ringsmose is the institute of the Defense Academy and Anders Henriksen Center Leader at the Faculty of Law, University of Copenhagen.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.