Russian Analytical Digest No 221: Russian Natural Gas Exports to Europe

25 Jun 2018

By Simon Pirani and Roland Götz for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The article featured here was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 11 June 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Kremlin.ru. external page(CC BY 4.0)call_made

The Decline and Fall of the Russia–Ukraine Gas Trade

By Simon Pirani, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

DOI: 10.3929/ethz-b-000269440

Abstract

The Russia–Ukraine gas trade is being reduced to a shadow of its former self. Contracts between Gazprom and Naftogaz Ukrainy—for the import of Russian gas to Ukraine and the transit of Russian gas across Ukraine to European customers, in 2009–19—remain in place, but have been broken by both sides. Commerce has been unable to disentangle itself from politics. This analysis examines the current state of affairs after the final ruling of the arbitral tribunal and gives an outlook for the period beyond 2019.

Introduction

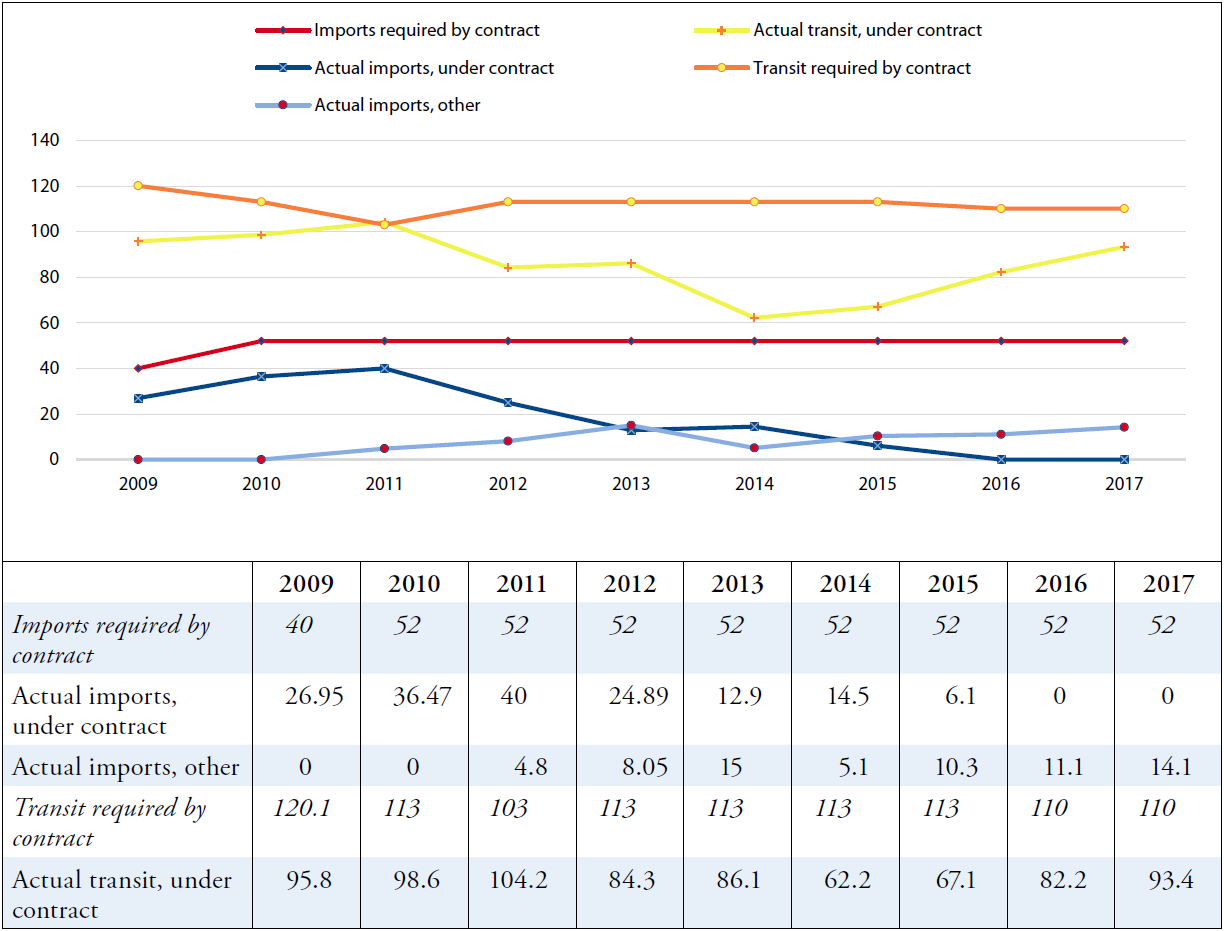

The Russia–Ukraine gas trade is being reduced to a shadow of its former self, as the data in Table 1 at the end of the text indicates (p. 6). Contracts between Gazprom and Naftogaz Ukrainy—for the import of Russian gas to Ukraine and the transit of Russian gas across Ukraine to European customers, in 2009–19— remain in place, but have been broken by both sides. The breaches were the subject of one of the largest ever commercial arbitration disputes, initiated at the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce in April 2014 after the overthrow of Viktor Yanukovich’s government and the outbreak of war in eastern Ukraine. The arbitral tribunal’s final ruling, on the transit contract, was issued on 28 February and was immediately denounced by Gazprom. Commerce has been unable to disentangle itself from politics. Post-2019 arrangements will be worked out with political relationships between Russia, Ukraine and Europe at an all-time low. Russian gas imports by Ukraine will probably stop all together, and transit be reduced to a bare minimum.

Arbitral Tribunal’s Final Ruling

The arbitral tribunal’s most important decisions were:

- That Naftogaz had been overcharged for imports between April 2014 and November 2015, but that retrospective claims relating to 2009–14 were outside its jurisdiction; that the oil-linked price formula in the contract should be replaced by prices linked to those in the German gas market (at the NCG trading point).

- That the “take-or-pay” requirement on Naftogaz in the sales contract should be drastically reduced, from 41.6 bcm/year to 4 bcm/year.

- That the clause preventing resale of Russian gas is null and void; and that gas delivered to separatistcontrolled areas could not be invoiced to Naftogaz.

- That Gazprom had defaulted on its obligation to transport minimum volumes under the transit contract in 2009–17. Gazprom was required to pay $4.63 billion to Naftogaz for this, from which was subtracted $2.02 billion owed by Naftogaz for unpaid invoices in 2014, plus interest. The net payment required from Gazprom was $2.56 billion.

- That Naftogaz’s claim, that new transport tariffs introduced by the Ukrainian regulator in 2016 should be applied, be rejected. (For further detail, see Pirani 2018)

Reactions

Gazprom managers denounced the arbiters’ decision on the transit contract as “asymmetrical,” and took three actions in protest against it.

First, on 1 March, immediately following the arbiters’ decision, they cancelled a planned resumption of direct gas exports to Ukraine. The resumption had been expected, in line with the tribunal’s ruling on the supply contract, after an interruption of more than two years. Gazprom managers cancelled it and returned prepayments made by Naftogaz. The change came as a surprise to Naftogaz, which stated on 3 March that it had had to take emergency action to ensure customers were supplied with alternative volumes. Gazprom management did not present the cancellation as related to the arbiters’ decision; on the contrary, Aleksandr Medvedev, deputy CEO, said that additional agreements that needed to be in place prior to delivery had not been made. No substantial sticking-point holding up such agreements was reported, however.

Second, Gazprom wrote to Naftogaz on 3 March to initiate termination of both contracts. There is provision in the contracts for disputes, including those leading to termination, to be resolved via Stockholm arbitration. It has been reported that this issue is under discussion by the two companies; it may be superceded by their negotiations on post-2020 arrangements for transit.

Third, Gazprom lodged an appeal with the Stockholm arbitration court against the decision on the supply contract, and stated that it will lodge a similar appeal regarding the transit contract. Vladimir Chizhov, Russian ambassador to the EU, has stated that hearing these appeals is expected to take at least six months.

During these additional arbitration and appeal processes, the current contracts remain in place. They both expire on 31 December 2019. This is presumably the basis of the assurance given by Aleksandr Novak, Russian energy minister, on 6 March—in response to expressions of concern by Maroš Šefčovič, EU vice president for the energy union, on 2 March—that Russian gas deliveries to EU customers remain reliable, notwithstanding Gazprom’s statements in response to the arbiters’ decision.

There has been no noticeable concern expressed about these events by the European companies that purchase Russian gas, since there has been no physical interruption in supplies to Europe, and none is expected. In European political circles, though, these events may redouble concerns about the level of dependence on Russian gas.

Outlook

In the medium and long term, given the opening-up of the Yamal gas fields, Russian gas exports to Europe could not only be maintained at their current level (179 bcm in 2016 and 194 bcm in 2017), but increased. Russia’s reserve base will continue to provide the lowest-cost gas for export to Europe through the 2020s. The limits on Russian exports are likely to be set not by supply constraints, but by the European Commission and European governments, which are anxious to minimise dependence on Russian gas, for both strictly commercial, and political, reasons. These broader debates and negotiations form the background to the settling of important questions about arrangements for gas transit across Ukraine after 2019. Russia is determined to reduce its reliance on Ukrainian transit, and the European Commission believes it is strategically important to retain it.

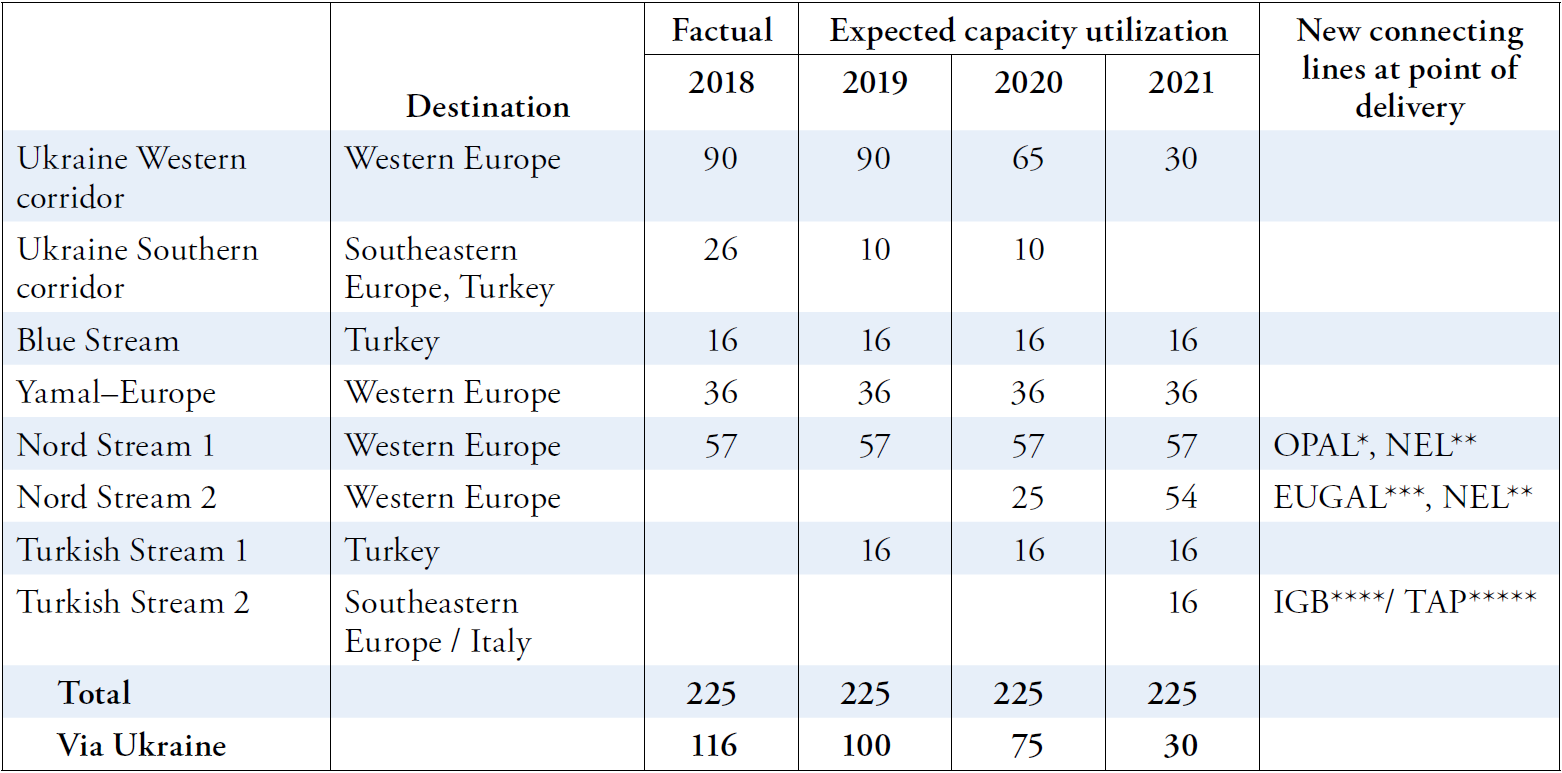

The ultimate aim of Gazprom’s transit diversification strategy, to reduce gas transit across Ukraine to zero, cannot be achieved by 2020, and probably not for some years afterwards. Gazprom will certainly require transit across Ukraine immediately after the current contracts expire (in 2020–21), and might need some level of residual transit even if and when the first two major transit diversification pipelines, Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream, are completed.

Nord Stream 2 retains its target of being operational by the end of 2019, but this is unlikely to be met, due to outstanding regulatory issues raised by the European Commission and the Danish parliament. TurkStream is under construction, and the first line, which will transport Russian gas to western Turkey, is due to be completed by the end of 2019. The second line, to carry Russian gas to Turkey for further transport to south-eastern Europe, could also be completed in a comparable time frame, but it is not clear which of several alternatives (a proposed pipeline from Greece to Italy, expansion of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, or a Bulgaria–Turkey interconnector) will be used for onward transport of gas to European destinations.

A number of scenarios, depending on whether, and on which time scales, new pipelines are constructed, were discussed in an OIES publication in 2016 (Pirani and Yafimava, Russian Gas Transit Across Ukraine Post-2019 (NG105)). The scenario that now seems certain to apply in early 2020 is that no new pipelines will be built, but the capacity cap on the OPAL pipeline will be lifted (albeit partially rather than completely). In this case, Gazprom would, without Ukrainian transit, be able to serve the Czech republic, Slovakia, Austrian and Hungary at 2014 export levels and above, but be unable to meet a significant part of Italian demand, and be unable to make some deliveries to south eastern European countries and Turkey.

By the mid-2020s, a scenario in which two strings of TurkStream and two strings of Nord Stream 2 are built may well apply. In this scenario, even at a high level of exports totalling 180 bcm, Gazprom would be able to serve all its European markets, and Turkey, without using Ukrainian transit. The caveat that now needs to be added is that, potentially, demand for Russian gas to Europe could exceed that level. Gazprom would not realistically, therefore, be able to close the door on Ukrainian transit completely.

So in 2020–21, Gazprom will require 40–75 bcm/ year of transit capacity across Ukraine. If and when Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream are fully operational, the capacity required could decline, theoretically to zero, but in reality Gazprom would prefer to retain the option of transporting residual volumes across Ukraine. Ukraine and the European Union, for both political and commercial reasons, favour the continuation of transit. There are three possible frameworks for this:

1. The conclusion of a medium-term (3 to 5 years) and more flexible transit contract between Gazprom and the Ukrainian Transmission System Operator (TSO), for example, for 30 bcm/year of capacity. It is possible that, now Ukraine has adopted EU-compatible market rules, Naftogaz could buy capacity from the TSO and sell it to Gazprom.

2. A series of shorter-term contracts for smaller volumes. This is likely if efforts to put in place a more robust arrangement fail.

3. The shifting of the delivery point in Gazprom’s current long-term sales contracts from Ukraine’s western border, and other European sales points, to the border of Russia and Ukraine. This approach, long supported by the Ukrainian government and European politicians, has no obvious commercial rationale from Gazprom’s point of view. First, the company would need to reopen negotiations on its long-term contracts with major European purchasers. Second, selling gas on the Russian border would set a precedent with unpredictable and potentially undesirable consequences. Gazprom’s major European customers have also been lukewarm to this proposal, which implies a big upheaval in trading arrangements. And finally, the political context, of Russia’s relations with Ukraine and European countries at a low ebb, is not conducive to a move in this direction. All these things considered, it is unlikely.

These three possibilities apply up to the mid-2020s. Thereafter, it is possible, assuming no thawing of political relations, that only residual volumes that cannot be transported by other routes will be transited across Ukraine. This could imply zero transit in some periods.

Direct Russian exports of gas to Ukraine, which ceased in November 2015, seem unlikely to resume, without a political sea-change. Ukraine’s gas consumption has fallen sharply due to military conflict, economic crisis and some energy saving—and is now supplied from domestic production and imports from EU countries.

The Ukrainian Transport Business

One crucial element that will shape gas transit across Ukraine after 2019 is the reform of Ukrtransgaz, the Naftogaz subsidiary that operates Ukrainian gas pipelines and storage facilities. Ukrainian energy law provides for these assets to be unbundled, i.e. to be separated- out from Naftogaz’s other businesses (oil and gas production, supply, etc) within 30 days of the completion of the Stockholm arbitration. Nevertheless, major obstacles remain.

- First, the government and Naftogaz management have different views of how unbundling should be implemented. A government decree (no. 496, July 2016), required that Ukrtransgaz’s transmission assets be transferred to a new state-owned entity, Main Gas Pipelines of Ukraine, after the arbitration hearings, and that storage assets be unbundled subsequently. Naftogaz managers, by contrast, have set up a new subsidiary, Ukraine Gas Transmission System Operator, to manage the transmission system but not the storage assets; they argue that the holding company should retain control of the whole system while unbundling proceeds. The question of whether the storage assets should be unbundled together with the pipelines, or separately, is complicated by legal cases, brought by oligarchical industrial groups, in respect of stored gas.

- Second, both government and Naftogaz agree that European partners should be brought in, but the form of cooperation is not yet clear. There are prospects for involving European TSOs as partners, with political support from the EU. Under a Memorandum of Understanding signed in April 2017 with Naftogaz and Ukrtransgaz, Snam of Italy and Eustream of Slovakia have produced proposals for unbundling. Naftogaz management is also in talks with other European TSOs.

- Third, Naftogaz has long cross-subsidised the supply of cheap gas to households and district heating companies, and the burden of non-payment especially from the latter, with revenue from sales to industrial customers and from transit services. Since 2014, market reform has reduced Naftogaz’s sales to industrial customers substantially; without transit revenues, the cross-subsidy scheme would be in danger of collapsing. While all sides agree that the crosssubsidy needs to be phased out, that is tricky socially and politically—especially with a presidential election approaching in March 2019—and this affects the timing and manner of unbundling.

The biggest unknown in the unbundling puzzle, though, is the post-2019 size and shape of the transit business. Perhaps only when this becomes clearer will this aspect of market reform move forward.

Conclusions

Hopes that the conclusion of the arbitration case would allow the companies involved to draw a line under the past, and negotiate commercial arrangements for post- 2019 transit, appear not to have been borne out. Gazprom’s appeal against the decision is unlikely to produce a substantially different result, and its proceedings for termination of the current contracts is irrelevant to the arbiters’ decision. However, these actions will overshadow possible negotiations on post-2019 arrangements.

Moreover, during this year and next, while the arbitration appeal is in progress, other crucial issues for Russia’s gas trade with Europe will also be in the process of being negotiated, including the final outcome of the EU Director General of Competition (DG Comp) investigation into Gazprom pricing, and the legal and regulatory obstacles to the Nord Stream 2 and Turk- Stream pipelines.

Gazprom’s reactions to the tribunal’s decision appeared to be a form of protest rather than a way of pursuing a business strategy. Its major European customers may not be unduly concerned. But the appearance given, that it was ready both to suspend gas deliveries to Ukraine that were paid for and expected, and to terminate both supply and transit contracts without anything to put in their place, will reinforce political rhetoric in Europe about reducing dependence on Russian gas supplies.

The European Commission after 2014 brokered the arrangement of “winter packages” that enabled transit and gas supply to Ukraine to continue, despite the political tensions. It may again feel motivated to intervene— although there is a time constraint, in that the current European Commission’s term of office ends on 31 October 2019.

The decline of the Russo–Ukrainian gas relationship will continue. From 2020, transit of Russian gas across Ukraine will continue, but at much lower volumes. Direct sales probably will not. By the mid-2020s, all transit could cease. The only realistic possibilities of change depend on an improvement of political relationships, which in turn probably depend on a significant shift in the situation in eastern Ukraine.

Further Reading

Simon Pirani, After the Gazprom-Naftogaz arbitration: commerce still entangled in politics. Oxford Energy Insight 31, March 2018.

About the Author

Simon Pirani is a Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Ukraine: Natural Gas Transit and Imports

Table 1: Ukraine: Natural Gas Transit and Imports under the Contracts (bcm)

The Nord Stream 2 Dispute: Legal, Economic, Environmental and Political Arguments

By Roland Götz, Berlin

DOI: 10.3929/ethz-b-000269440

Abstract

Since Gazprom announced its intention to double the capacity of its Baltic Sea pipelines, the dispute that has already flared up over Nord Stream has been repeated with even greater intensity. Little attention is paid to the fact that the fate of Nord Stream 2 will ultimately be decided not by the exchange of arguments, but by its legal state. Gazprom has the right to lay offshore pipelines if they comply with the international rules of maritime law and certain limited regulations of the coastal states. The European Commission and the European Parliament, under the strong influence of Eastern European politicians who are critical of Russia, are therefore trying to prevent the completion of Gazprom’s pipeline strategy by extending EU law to the open sea.

Gazprom’s Pipeline Strategy

The Soviet Union sent its natural gas exports almost exclusively through the Ukrainian gas transit system, which had been built up since the 1970s. In order to become independent of Ukraine’s transit monopoly, Gazprom began construction of gas pipelines, which circumvented Ukraine. The first such export route was created in 1997 with the Yamal–Europe pipeline leading through Belarus and Poland to Germany. The share of Ukrainian transit decreased to about half of Russia’s gas exports when the Blue Stream pipeline through the Black Sea to Turkey went into operation in 2003 and the two lines of Nord Stream (Nord Stream 1) went into operation in 2011.

In addition, Gazprom resumed its earlier plans to double the capacity of the Baltic Sea pipelines with Nord Stream 2 in 2015. Should they go into operation at the end of 2019, the Ukrainian gas transit system still would have to be used, albeit to a lesser extent, simply because the second line of its connecting pipeline in Germany (EUGAL) will not be completed until the end of 2020. In the longer term, some of Ukraine’s Western corridor transit pipelines will continue to be needed for Russia’s gas exports, because they are the only way to cover seasonal fluctuations and a possible increase in European gas demand.

After Gazprom had to abandon the plan of the South Stream pipelines (which were supposed to cross the Black Sea to the Bulgarian coast), because its connecting pipelines running through EU countries collided with EU gas market regulations, Russia and Turkey decided in 2016 to build the Turkish Stream pipeline system running through the Black Sea into the western part of Turkey. It is expected to supply Turkey from the first line beginning in 2020 and from the second line: Bulgaria, Romania and other Balkan countries (in reverse operation via the Trans Balkan pipeline or via newly built interconnectors), as well as Greece and Italy via the Trans Adriatic pipeline from 2021 (see Table 1 at the end of the text).

Gazprom is interested in shifting most of the remaining gas transit via Ukraine to Nord Stream 2 and Turkish Stream, primarily because this will reduce the risk of supply interruptions that threaten to occur after the expiry of the gas transit agreement concluded with Naftogaz Ukrainy in 2009 and valid until the end of 2019. This risk is high because Ukraine stopped importing gas from Russia at the end of 2015, so that the country no longer has to fear a supply stoppage and could be tempted to demand unreasonably high transit charges.

The EU Commission’s Strategy

The European Commission and the European Parliament, which are both under the influence of Eastern European politicians critical of Russia, do not consider Nord Stream 2 necessary for Europe’s gas supply and reject Gazprom’s intention to further reduce Ukraine transit. In order to secure transit fees of two to three billion US dollars per year for Ukraine, which depend on the maintenance of a high transit volume (2017: 93 billion m3), the Commission—in charge of this issue is Vice-President for Energy Union Maroš Šefčovič— intends to raise high legal hurdles for the commissioning of Nord Stream 2. After a first attempt failed in February 2016 due to the objection of its own legal service, the Commission asked the Council of the European Union on July 2017 for a mandate to negotiate with Russia on the validity of EU gas law for Nord Stream 2. In its opinion of September 2017, the Council’s legal service rejected this request and confirmed the inapplicability of the EU gas directives on gas pipelines that run into the EU from third countries (“import pipelines”). In response to this, the EU Commission presented a draft amendment to the 3rd Gas Directive on November 2017, which extends its scope to import pipelines. As Turkish Stream leads to Turkey, only its connecting pipelines to Bulgaria and Greece will be affected by the possible new regulation.

In the area of gas market law, the EU Commission intends, redefining the term interconnector, to extend the scope of the 3rd Gas Directive to include import pipelines. This would apply the same principles to them as to pipelines within the EU: The separation of gas production and gas transport (unbundling), non-discriminatory access to gas pipelines (third-party access) and transparency in pricing and the setting of the tariff. If the hitherto sceptical European Council (and the European Parliament, which is in favour of tightening the law), adopt it, EU countries must, if the third countries concerned are not prepared to amend their energy laws, prohibit their own energy companies from importing gas via the relevant pipelines.

The Commission justifies its proposal on the grounds that there was a legal void in the operation of import pipelines and that a conflict of laws would have to be eliminated. It wants to fill this void and eliminate the resulting conflict of legal norms through negotiations with the third countries concerned. However, the Council’s legal service has already twice rejected the assertion of a gap in the law, as the operation of Nord Stream 2 is governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which is based on the principle of freedom of the seas. In the segments of the Baltic Sea completely covered by the “exclusive economic zones” of the coastal states and their continental shelves, the special concerns of the coastal states (right to extract natural resources, protection of the natural environment) must be observed. In territorial waters (12-mile zones), additional national regulations of the coastal states apply, but not the EU gas directives, which means that no regulatory conflicts can arise with them.

The Commission considers that the new regime builds on established practice. This is true for gas relations with Norway, but not with Russia. Gazprom would have to transfer ownership of Nord Stream 2 to an independent company to meet the demand for ownership unbundling and Russia’s parliament would have to allow other gas producers to use the pipeline as well, reversing Gazprom’s export monopoly on pipeline gas introduced in 2006. Regardless of the fact that these conditions would lead to a desirable reform of Russia’s gas market, it is highly unlikely that Gazprom and the Russian Duma will accept them under pressure from the EU. Nor is it clear what room for negotiation the EU Commission intends to make use of, as it cannot deviate from the core elements of its own initiative. A failure of the negotiation process is therefore foreseeable, although this would be entirely in line with the critics of Nord Stream 2. A temporary derogation from the provisions of the Gas Directive, which could be granted at Germany’s request, would require the Commission’s approval, which will hardly be granted as it would contradict its concern to prevent Nord Stream 2 from going into operation immediately.

Economic and Environmental Arguments

The proposed amendment to the Gas Directive and its accompanying documents refer to Article 194 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (Lisbon Treaty) as justification. It calls for EU energy policy to ensure and improve the functioning of energy markets, security of supply, energy efficiency, energy saving, the development of new and renewable energies and the interconnection of energy networks. How this is to be achieved by the proposed extension of the scope of the 3rd Gas Directive is not outlined by the Commission, which expressly refused to submit an impact assessment of its proposal. The Commission ignores the fact that Nord Stream 2 would meet some of the requirements of Article 194 of the Lisbon Treaty better than the existing Ukrainian gas transit network: Like Nord Stream 1, Nord Stream 2 will be supplied by gas from the Yamal Peninsula, where Russia’s largest gas reserves currently under development are located. The route from the Yamal Peninsula to the Baltic Sea will save around 2000 km compared to the route to the Ukrainian border, which is not only economically more efficient, but also ecologically more advantageous, because correspondingly less natural gas has to be burned in compressor stations. In addition, the new pipelines already laid and to be built in Russia and across the Baltic Sea are less prone to repairs and more energy-efficient than the Russian and Ukrainian gas pipelines which date back to the Soviet era and most of which have already exceeded their planned service lives. It was not until 2018 that the programme announced in 2008 to reconstruct the Ukrainian gas transport system, whose costs were estimated at three billion US dollars, began with the modernisation of one compressor station, for which 80 million euros will be invested.

The Commission’s argument that Nord Stream 2 would allow Gazprom to increase its dominance over the European gas market is not correct, as Gazprom’s market share does not depend on transport routes, but on supply capacities and prices of competitors (including suppliers of liquefied gas).

Foreign Policy Arguments

Opponents of Nord Stream 2, which include many experts and politicians from EU countries, Ukraine and the USA, claim that this gas pipeline, like Nord Stream 1, is not an economic, but a political project aimed at weakening Ukraine and increasing Russia’s influence in Europe. Not only would Germany be geopolitically upgraded as a central hub for gas from Russia, but it would also be tempted to move closer to Russia politically, regardless of the interests of its Eastern European neighbours. But it is undisputed that major infrastructure projects can have political consequences and side effects. This does not justify the reverse conclusion that the purpose of these projects is political. Gazprom planned its programme of bypass pipelines, which included Nord Stream 2, long before the outbreak of the Ukrainian conflict and the increasing alienation between Russia and the West. That is why the assertion that it aims to strengthen Russia’s ability for an attack on Ukraine is plucked out of the air. The fact that Germany (and not only through the Baltic Sea pipelines) plays a role in Europe as a distribution centre for natural gas is due to its geographical location and is not a prerequisite or consequence of political rapprochement with Russia.

The desire to condemn Russia’s Ukrainian and Syrian policies plays a role in the resistance against Nord Stream 2. However, the appropriate way to achieve this is to extend the sanctions imposed on Russia and not to manipulate EU gas market rules.

A New Transit Regime

The German Chancellor’s statements at a press conference with the Ukrainian President on 10 April 2018, according to which Germany could only support Nord Stream 2 if Ukraine is guaranteed the continuation of gas transit, were interpreted as a change in the attitude of the German government. However, on this occasion, Merkel only reiterated the position which she had already taken in the past. The question of a transit guarantee is not “if” but “how much”, because Gazprom is prepared to continue transit through Ukraine, as Gazprom boss Miller has repeatedly stated. However, the transit volume of 10–15 billion m3 per year he mentioned is too small to guarantee Europe’s security of supply and the technical functioning of the Ukrainian gas network and gas storage facilities, for which a sufficient gas pressure is required.

In the 2009 transit contract Gazprom had agreed with Naftogaz Ukrainy a minimum annual transit volume of 110 billion m3, but did not comply with it. In February 2018, the Stockholm Arbitration Court (after netting Gazprom’s two billion US dollars in claims on Naftogaz) ordered Gazprom to pay 2.6 billion US dollars in compensation for this. Gazprom is also threatened with billions of dollars in compensation payments for 2018 and 2019 due to once again falling below the minimum transit limit. If Ukraine does not recover at least these amounts and both sides are prepared to set transit charges fairly, a new transit agreement could be concluded providing for an adequate transit volume. Or Gazprom could declare its willingness to supply gas at Ukraine’s eastern border in line with the demand arising there. The gas will then be forwarded in accordance with the provisions of Ukraine’s then established new gas market model. This would avoid a non-contractual situation and an otherwise impending gas crisis at the beginning of 2020.

Further reading

Aurélie Bros, Tatiana Mitrova, Kirsten Westphal: German–Russian gas relations. A special relationship in troubled waters. Berlin 2017, <https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2017RP13_ wep_EtAl.pdf>.

European Commission: Proposal for the amendment of the 3rd Gas Directive and accompanying documents, 8.11.2017, <https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/commission-proposes-update-gas-directive-2017-nov-08_en>.

European Council, Opinion of the Legal service, 1.03.2018, <https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ NS2-Gas-Legal-Opinion-March-2018.pdf>.

European Council, Opinion of the Legal service, 26.03.2018, <https://www.euractiv.com/wp-content/uploads/ sites/2/2018/03/2Opinion-Council-LS-EC-amendment-3rd-Gas-Directive.pdf>.

James Henderson, Jack Sharples: Gazprom in Europe. Two “Anni Mirabiles”—but can it continue? Oxford 2018, <https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Gazprom-in-Europe-%E2%80%93-two- Anni-Mirabiles-but-can-it-continue-Insight-29.pdf>.

Jack Sharples: Ukrainian gas transit. Still vital for Russian gas supplies to Europe as other routes reach full capacity. Oxford 2018, <https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Ukrainian-gas-transit-Stillvital- for-Russian-gas-supplies-to-Europe-as-other-routes-reach-full-capacity-Comment.pdf>.

Katja Yafimava: The Council Legal Service’s assessment of the European Commission’s negotiating mandate and what it means for Nord Stream 2. Oxford 2017, <https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ The-Council-Legal-Services-assessment-of-the-European-Commissions-negotiating-mandate-and-what-it-meansfor- Nord-Stream-2.pdf>.

A German version of this paper external pagewas publishedcall_made in Russland-Analysen 354, pp. 8–11.

About the Author

Dr. Roland Götz studied the Soviet economic system and the post-Soviet economies at the Federal Institute for Eastern European and International Studies in Cologne and at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin.

Capacities of Main Gas Transit Pipelines from Russia to Europe and Turkey

Table 1: Capacities of Main Gas Transit Pipelines from Russia to Europe and Turkey (bcm)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.