Belarus between East and West: The Art of the Deal

10 Sep 2018

By Benno Zogg for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in September 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Disputes over border management, gas prices, and the recognition of Crimea: Belarus is increasingly at odds with its closest ally Russia. President Lukashenko’s regime emphasizes its independent foreign policy as a country between Russia and the West. There are signs of Belarus strategically reorienting, but the actions taken also mirror tactics used to extort lucrative concessions from both East and West.

During the Belarusian celebration of independence in July 2018, President Alexander Lukashenko stressed that Belarus would not choose between East and West. Belarusians would choose independence, peace and partnerships with other states. He thus reaffirmed statements he made at the Minsk Dialogue Forum in May 2018, a for Belarus unprecedentedly large conference on Eastern European security that was well-attended by Western researchers and policy advisors. Since 2014, Belarus stresses its role as a bridge builder and mediator in the Ukrainian conflict. At the same time, the government is pursuing a policy of strengthening national identity.

In Russia, both officials and the state-controlled media are increasingly criticizing Belarus’ lack of loyalty and its commitment to the alliance. Lukashenko is personally criticized for his perceived attempts to ingratiate himself with the West. Tensions are further exacerbated because Belarus does not recognize the “reunification” of Russia with Crimea, rejects the establishment of a Russian air base on its territory, and introduced a limited visa exemption for Western tourists.

These recent developments directly contradict the prevailing image in the West to date; that Belarus is Russia’s staunchest ally. Belarus is indeed heavily dependent on Russian energy subsidies and markets, a member of all Russian-led projects for economic and military integration, and the countries have close cultural ties. It is therefore remarkable and significant for debates on European security that Belarus, neighbor to Ukraine and strategically located between Poland and Russia, has begun shifting its foreign policy priorities since 2014.

Belarus in between

Belarus, with its ten million inhabitants, is located on the East European Plain. Its only experience of independent statehood was the Belarusian People’s Republic proclaimed under German occupation in 1918, which lasted for only a year. After that, Belarus developed into probably the most Soviet of all Soviet republics.

President Lukashenko, who came to power in 1994 in the last free election in the country after independence, has preserved Soviet heritage in many ways, including through state symbols and maintaining the name of the secret service “KGB”. Hasty economic privatization, like what was seen in Russia or Ukraine, did not occur in Belarus. This limited the development of a powerful oligarchy and the commensurate problems with inequality. The “market socialist” economy remains state-controlled in many areas and is not very dynamic. The IT sector is flourishing, but overall the private sector produces only an estimated 30 percent of Belarus’ GDP. Unemployment is low. Overall, the Belarusian economy has grown above average since the end of the Soviet Union but has stagnated in the wake of the Russian economic crisis since 2014. Belarusian infrastructure is in consistently good condition. Access to education and health care is free – compared to most former Soviet countries, their quality is considered better. Civil servants and security services are also generally considered competent and less corrupt than in other former Soviet states. Grants from abroad in the form of bilateral subsidies and loans from development banks are indispensable for financing the current system.

After the economy began to stagnate, the government increasingly emphasized the value of stability: Belarus has been spared waves of migration, terrorist attacks (apart from an attack on the Minsk Metro in 2011) and a war like in Ukraine. Of all the six states geographically located between the EU and Russia in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, which are members of the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP), only Belarus has had no territorial conflict. This stability is due not only to geographical and historical factors, but is recognized as a consequence of the government’s balanced governing tactics, which the population appreciates.

The Lukashenko regime’s overriding interests are self-preservation and a generally high degree of control. The result is an overzealous restriction on democracy and freedom of expression and assembly. The organized opposition is oppressed, divided and marginalized, and funded from abroad. Lukashenko’s regime is autocratic but not dictatorial. The system allows just as much freedom as a stable, managed economy requires and that meets the basic needs of personal freedoms for a majority of citizens. Lukashenko’s paternalistic policy often corresponds with the prevailing opinion of his people, and therefore garners some automatic support. These policies likely include limited LGBTQ rights and the retention of the death penalty. However, Lukashenko’s policy differs from popular opinion in many respects. The majority of the Belarusian population approves the annexation of Crimea for example, which may be partly due to omnipresence of Russian media throughout the state.

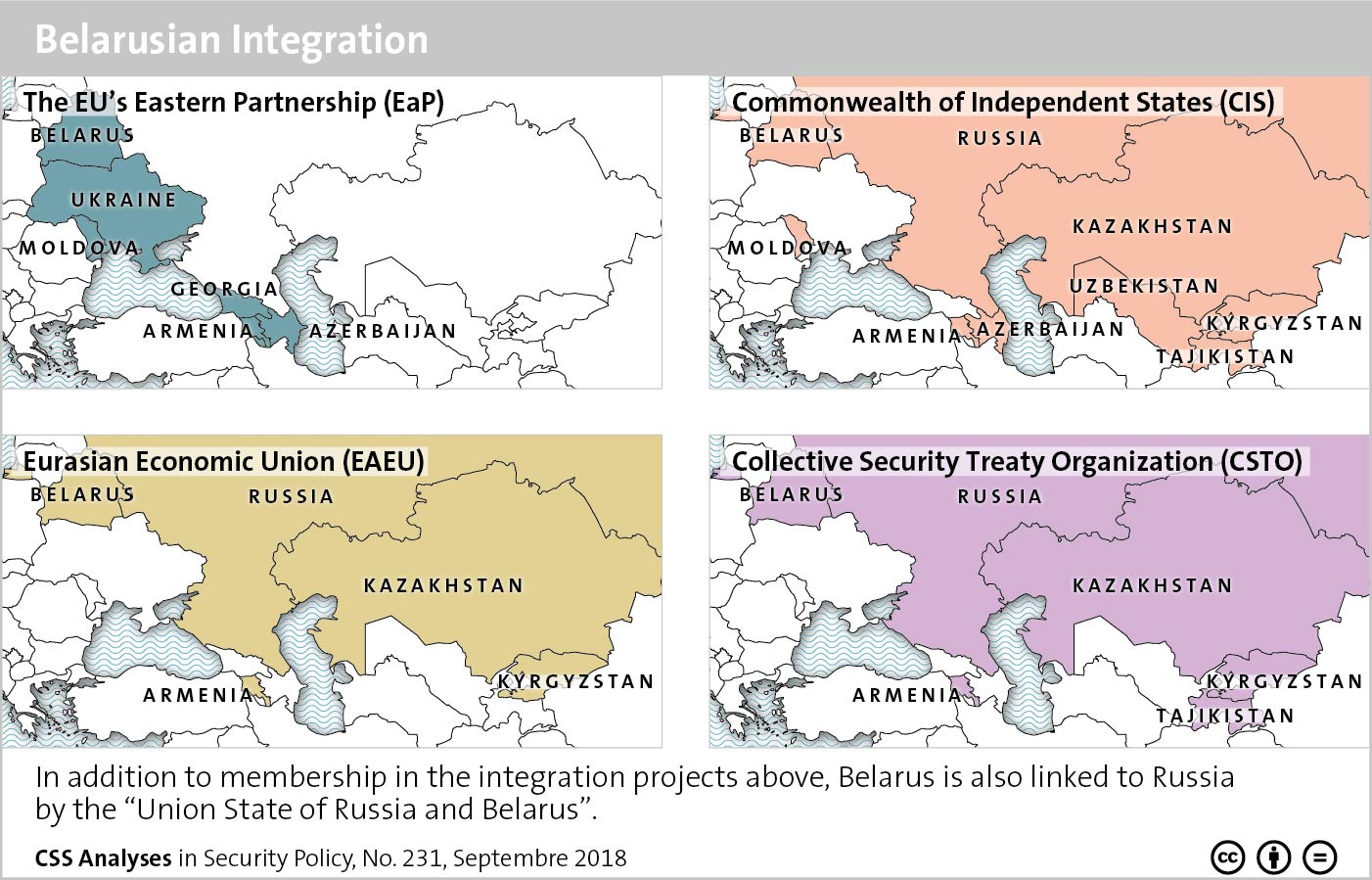

State of the Union State

For a long time since the end of the USSR, Russia had not believed that Belarus, nor Ukraine, can pursue an independent foreign policy. Accordingly, disputes in recent years have led to irritation in Moscow. However, there are good reasons why until a few years ago Belarus was regarded by the West, but also by Russia itself, as Russia’s “little brother” and satellite. No country is as closely tied to Russia as Belarus. 70 percent of Belarusians speak Russian at home, despite recent government attempts to promote the use of the Belarusian tongue. In addition to membership in all multilateral Russian integration projects (see chart), the countries are linked by the vague “Union State of Russia and Belarus”, based on treaties signed since 1996. The integration of the two countries includes free movement of persons, a common economic area, military assistance in the event of an attack and even joint air defence. The market share and influence of Russian companies in Belarus, including in key industries, is high.

Belarus hosts two Russian military bases, but no combat units may be stationed there. The army, which is not widely considered as a powerful force in the region, and the Ministry of Defence are considered pro-Russian and are influenced by training in Russia. Military cooperation entitles Belarus to purchase military equipment from Russia at a discount. For Russia, Belarus is strategically important as a transit country for energy and because it almost borders the Russian exclave Kaliningrad. The remaining “Suwalki gap” of only 65 kilometers is, in turn, NATO’s only land connection to its Baltic members.

Moscow buys its ally’s loyalty with loans and energy discounts worth several billion dollars a year. The (re)export of energy and petrochemical products is an important source of hard currency for Minsk. Under Vladimir Putin, however, bilateral integration has slowed. In addition to alleged personal differences with Lukashenko, the pragmatist Putin is unwilling to subsidize Belarus almost unconditionally. The two states have regularly disagreed over energy prices, which has led to hostility and the suspension of supply. Russia imposed an import ban on Belarusian dairy products in 2009, which was referred to as the “milk war”. Lukashenko is credited with maneuvering his position to gain an advantage in each case, also through skillful tactical negotiations implying a closer relationship with the West.

Russia has also indicated an ambition that is deeply troubling to the Belarusian administration. A speech Putin gave in 2011 enraged Minsk when he welcomed, and not for the first time, the idea of integrating Belarus as a Russian province. Minsk’s decision to not recognize the regions of Abkhazia, South Ossetia nor the integration of Crimea, in turn, causes disgruntlement in the Kremlin.

Turning Point: Crimea

Starting with the overthrow of the Ukrainian government and continuing throughout Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent interference in eastern Ukraine, Russia’s activities since 2014 have shocked Belarus. The Belarusian government has been fostering a moderate nationalism to create a sense of identity distinct from Russia. Minsk emphasized its “situational neutrality” in the Ukrainian crisis and continued business with both countries. It circumvents Russia’s counter-sanctions, for example by relabeling goods from the West and exporting Norwegian seafood and Turkish kiwis as Made in Belarus to Russia. Russia is also irritated by its neighbor’s visa regime, which has allowed Western nationals to stay for short periods without a visa since February 2017. In response, Moscow has unilaterally reintroduced border controls.

Lukashenko’s actions displeased Russian nationalists on account of his apparent perfidy and displeased liberals for extorting subsidies. Russian experts and media, which are often state-controlled, accuse him of disloyalty for this strategy. Conveniently, this condemnation also further discredits the existence of a viable “second Russia”, a stable alternative to Putin’s system. The Russian population, among whom Lukashenko was very popular for a long time, increasingly sees him as an opportunist. Yet despite the growing divide, no other country remains as close to Russia in terms of values, culture and state structure as Belarus.

In order to emphasize the value and degree of Belarusian independence on the international stage, Belarus offered itself as a place for future international negotiations in 2014. This resulted in two “Minsk Agreements” on the Ukraine conflict in 2014/15. Minsk reaffirmed its willingness to participate in a possible UN peacekeeping mission in the Donbass. Within the framework of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Lukashenko is also attempting to initiate negotiations on a “Helsinki II”, a new edition of the CSCE Final Act of Helsinki 1975.

The West has become increasingly aware of the “in-between states” in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus as potential partners and is seeking to strengthen their independence. Disputes with Russia over imports and gas supplies have shown that even Belarus as Russia’s closest ally can be a victim of Russian interests. This background may help explain why Western sanctions against Belarus were lifted in 2016. The latest rapprochement with the West, however, has hardly led to an improvement in the human rights situation in Belarus. Opposition and free media remain oppressed and the death penalty is still practiced – perhaps Lukashenko recognizes the latter as a potential bargaining chip for future negotiations.

Switzerland and Belarus

Switzerland has an Embassy office in Minsk. In bilateral talks, Switzerland stresses the lack of human and political rights in Belarus, namely unfree elections, the use of the death penalty and the lack of freedom of the media and assembly. Humanitarian cooperation was discontinued in 2010 and had largely been limited to the victims of the Chernobyl disaster. In 2016, Switzerland, like the EU, lifted all financial sanctions and travel restrictions against Belarus. Relations have strengthened in recent years despite a modest volume of trade, for example through the formation of a “Parliamentary Friendship Group” in 2017. Negotiations for a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) agreement on free trade with the EAEU have been on hold since the Crimean annexation. Academic and political exchange on the practice of neutrality, which Belarus claims to apply situationally, could be fruitful.

From Belorussia with Love

The West is accustomed to Belarus’ skillful tactical and cyclical turnings to the West, while making rhetorical promises in the hope of Western concessions, loans and the lifting of sanctions. Hopes for meaningful political and economic reforms in Belarus often translated into no concrete action, like when the International Monetary Fund lent billions to the government in 2010/2011. Yet since 2014, Belarus seems to show an increased and genuine willingness for dialogue and rapprochement with the West. This is also an expression of internal power structures: the Foreign Ministry has always been considered more pro-European and more economically liberal than, for example, the security services, and seems to have gained influence.

In addition to considerations of foreign relations, Belarusian advances towards the West have economic justifications. The outcome of economic integration with Russia is mixed. Russia dominates the design and control of the economic area, and trade barriers remain. The economic crisis in Russia, caused by Western sanctions and the oil price collapse since 2014, revealed Belarus’ overdependence on the Russian market and put pressure on Belarus to support costly Russian counter-sanctions.

Although Belarus is the least engaged of all EaP countries, the EU offers opportunities for markets, investment, visa-free travel and support for its membership in the World Trade Organization. However, genuine cooperation relies on Belarus liberalizing, privatizing and improving the investment climate, which Minsk has so far avoided. Belarus is also the per capita Schengen visa world champion. Belarusians are eager to travel and are not as isolated as the authoritarian regime may lead one to believe. Negotiations to reduce the high cost associated with the Schengen visa have so far failed, however. According to surveys, the population would welcome greater cooperation with the EU, provided it does not jeopardize relations with Russia. This sentiment is reflected in the government’s pragmatic policy.

In the spirit of diversifying its political and economic partners, Minsk has also sought out potential partnerships in other regions. For example, Minsk does not want to be left out of the “New Silk Road.” Chinese investment in the country has subsequently increased. When Russia refused to supply Minsk with modern tactical missiles, Belarus decided to cooperate with China to acquire missile technology. Lukashenko’s youngest son Mikalai is learning Mandarin. However, bilateral trade and investment remain modest and a genuine strategic partnership with China, which Minsk hopes for, is not in sight.

Belarus’ Way Forward

The Belarusian economy is currently growing again, but this is attributed to the recovery in the region rather than any reform. Despite reservations among the population, the pressure to intensify timid economic reforms, privatize state-owned enterprises, strengthen the rule of law and diversify the economy will increase. Reforms can make the economy more robust and ultimately serve the national leadership’s desire for independence. Compared to the more corrupt, oligarchic Ukraine, reforms would be easier to implement in Belarus due to the competent civil service and stable institutions already in place. Gradual economic reforms that do not endanger the regime thus seem realistic. Domestic political changes are unlikely. No progress on democracy can be expected. The potential for a revolution is low.

In terms of Belarusian foreign policy since the Russian annexation of Crimea, the West has increasingly taken radical scenarios for Belarus into consideration. NATO analyses and simulations, which had previously regarded Belarus simply as Russia’s marching area, recently dealt with the possibility of an overthrow of the Lukashenko regime or a Russian invasion. It’s assumed that Russia will keep its neighbor within its sphere of influence at all costs, even if that necessitates orchestrating a coup. The allegedly tense personal relationship between Putin and Lukashenko may increase the likelihood of such a scenario. Belarus would have little political, economic, and particularly military means to oppose any significant Russian pressure. The Belarusian identity and army would not be strong enough to wage a war with Russia.

However, such scenarios are unrealistic in Belarus, despite the effective use of similar tactics in Ukraine. Belarus is not divided into pro-Russian and pro-European camps. The EU is not actively trying to remove Belarus from the orbit of its powerful neighbor. A majority of Belarusians are in favor of alliances with Russia. Lukashenko’s position among the elite is secure and he seems to be in the best of health. Despite animosities and increased unpredictability, the Kremlin believes he remains the best guarantor of a stable, pro-Russia Belarus. Ultimately, Belarus is indispensable for the European facet of Russia’s Eurasian integration projects. Intervening in its neighboring country would amount to Russia admitting that its previous policies and integration projects have failed. Lukashenko, in turn, exaggerates the danger of the Russian threat and the specter of a “Ukraine 2.0” scenario for the Western public to receive support with as few conditions as possible.

The two countries therefore depend on each other and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. China’s increasing influence will not alter this. But Russia will try to keep the Lukashenko regime on a shorter leash and strengthen its influence through economic dominance and the promotion of well-heeled civil society organizations. While Russia’s hold can manifest in a number of ways, a prime example would be if Belarus no longer resisted the establishment of a Russian air base on its territory. Belarus will continue to seek the maximum reward for their ongoing loyalty. As this dynamic appears stable, the regular tactical crises of recent years will continue accordingly.

With regard to Belarus’ relationship with the West, Belarus is gaining significant traction in Brussels as an in-between state that requires attention and a specific strategy. For the time being, geostrategic considerations will take precedence over efforts to promote values and human rights. Cooperation and compatibility between the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) would be in Belarus’ interest. But Lukashenko feels closer to the mostly autocratic EAEU members than to the liberal EU democracies, which often make normative demands.

The days when Belarus could be considered Russia’s compliant satellite are thus over, yet it will remain a close Russian ally as there is no alternative to the Belarusian state’s dependence on Russia. The Belarusian desire and willingness to act more independently between East and West has grown. Since 2014, the country has started repositioning itself strategically by emphasizing the value of its role as mediator and bridge builder and by increasing its efforts to strengthen the national identity. As it has done in the past, Belarus will still tactically alternate between approaching East and West. As Lukashenko attempts to branch out, what will garner praise from Brussels will incense Moscow. He has proven that he can successfully lead through tricky diplomatic environments with slow course changes, while catering to the needs of enough of his population. With these qualities, his regime is likely to remain stable for the foreseeable future.

About the Author

Benno Zogg is Researcher at the Think Tank of the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. His areas of interest include the post-Soviet space and development and security in fragile contexts.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.