The OSCE’s Military Pillar: The Swiss FSC Chairmanship

11 Dec 2018

By Christian Nünlist for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published on 5 December 2018 by the Center for Security Studies. It is also available in German and French.

In January 2019, Switzerland will assume the chairmanship of the OSCE Forum for Security Co-operation (FSC) in Vienna for four months. Following the Swiss Chairmanship of the OSCE in 2014, which was praised at home and abroad and was dominated by the management of the Ukraine Crisis, Switzerland will once again assume a visible role in the OSCE to promote peace and security in Europe.

In principle, the task is a routine matter, but since the outbreak of the Ukraine Crisis, nothing in the OSCE has been routine. The FSC has also suffered from the harsher political climate between Russia and the West. Nevertheless, especially in times of crisis, the FSC offers the opportunity for contacts between Russia and the West, especially military-to-military contacts. The FSC deals with politico-military issues. Among its most important tasks are the negotiation and adoption of politically binding decisions in the area of arms control and confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs), as well as ensuring compliance with the commitments entered into in this area by the OSCE participating States.

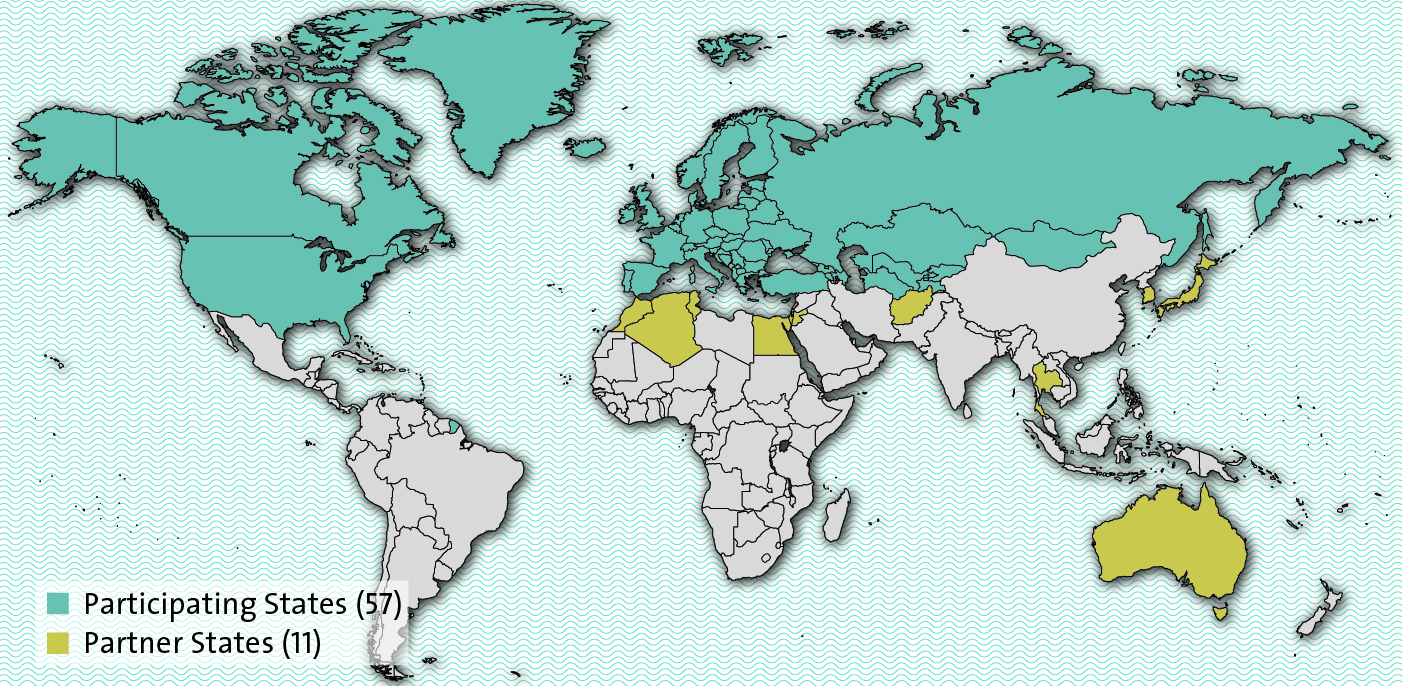

Promoting the effectiveness of the OSCE has traditionally been one of the priorities of Swiss foreign policy. With its approach of co-operative and comprehensive security and its commitment to inclusive dialogue, the OSCE reflects essential elements of Switzerland’s foreign policy strategy. Since July 2017, Swiss Ambassador Thomas Greminger has headed the organization as OSCE Secretary General. His election can be seen as a sign of appreciation within the OSCE for Switzerland’s constructive role in the world’s largest regional security organization and its 57 participating States, including the US and Russia.

Switzerland sees itself as a bridge-builder in the struggle between Russia and the West over the future European order. Switzerland supports both the OSCE’s crisis management in the Ukraine Crisis and a dialogue on core issues of European security, including an eventual re-launch of conventional arms control in Europe. Switzerland is also committed to better implementation of the OSCE’s existing arms control acquis and a modernization of CSBMs. These were agreed in the Vienna Document and include the exchange of information on armed forces, defense planning and expenditure, prior notification about major military exercises, and onsite verification.

How the FSC Works

Since 1992, the FSC has consisted of the Vienna-accredited delegations of the OSCE participating States, represented by diplomats and/or military advisers. Switzerland has already held the FSC Chairmanship four times, most recently in 2001 – 02, when it was still rotated in monthly intervals. The current four-month rotation principle was only introduced in February 2002 and allows the setting of priorities. In 2019, Switzerland will assume the modern, longer FSC Chairmanship for the first time. Switzerland now wants to skillfully set priorities and strengthen coordination with subsequent chairs.

In the FSC, as in all OSCE forums, all 57 participating States have equal rights. Decisions are always taken by consensus, giving every OSCE participating State a veto right. This often makes the decision-making process difficult and time-consuming, but consensual decisions, once taken, have great legitimacy. The work of the chairmanship is supported by the “FSC Troika”, consisting of the current FSC chair, the predecessor, and the successor. Switzerland will therefore be engaged in the FSC for a full year. The Troika sets the agenda and ensures the continued work of the FSC through joint coordination. For its part, the Troika is supported by the OSCE Secretariat.

Which country will take over the chair from Switzerland in April 2019 is currently still open. It would be Tajikistan’s turn, followed by the Czech Republic, Turkmenistan, and Turkey. Tajikistan has not yet made a definitive statement on whether it plans to carry out this task. This is rather an exception, because the vast majority of states, including small states, normally do so. The Czech Republic is working with two scenarios: Either it will assume the chairmanship in April 2019 directly after Switzerland, or it will do so later in the fall of 2019. Since Turkmenistan has not yet issued an official statement either, Turkey could assume the chairmanship as early as autumn 2019.

OSCE Participating States and OSCE Partner States (2018)

Innovative Ideas

The FSC began its work in Vienna on 22 September 1992 as an integral part of the CSCE. The 1990s were dynamic years for the CSCE/OSCE. After the end of the Cold War, pan-European ideas of inclusive, cooperative security with Russia invigorated the CSCE. The semi-permanent conference marathon was re-established as an organization at the end of 1994 – the OSCE.

Five negotiated normative basic documents stand out in the 25-year history of the FSC. Firstly, a “Code of Conduct on Politico-Military Aspects of Security” was adopted in December 1994. It is regarded as one of the OSCE’s landmark documents. The Code of Conduct deals with the defense policy of the participating States even in peacetime and obliges them to cooperate in security policy, to establish and maintain democratic control of the armed forces and to observe obligations under international law (such as the proportionality of the use of force to the fulfilment of internal security tasks). Despite having solemnly subscribed to the Code of Conduct in Budapest in December 1994, Russia’s deployment of its armed forces in Chechnya massively violated the Code just a few days later. This shows that it is very difficult for the OSCE to enforce CSMBs against major powers.

Secondly, the “Catalogue of Stabilizing Measures for Localized Crisis Situations” adopted in 1993 has been recalled more frequently in OSCE circles in recent years, as the document offers an interesting starting point for “status-neutral arms control” (i.e., mechanisms that can be applied even in controversial territories such as Crimea). Regarding potential conflict parties, the document states: “If these parties are not states, their status will not be affected by their identification and subsequent participation in the prevention, management and/or resolution of the crisis”. The document is not very well known, but actually contains useful confidence-building ideas for current conflicts, even though the catalog has so far never been used in practice. The document also covers irregular forces, non-state actors, and intra-state conflicts – and is therefore potentially suitable for modern, hybrid wars. States and non-state conflict parties, regardless of their status, could partner in arms control measures if all sides agree.

Thirdly, after the Dayton Agreement, discussions on regional arms control under the auspices of the FSC in January 1996 led to the “Agreement on Confidence Building in Bosnia and Herzegovina”. As a result, a large number of weapons systems were destroyed, and confidence was restored through arms control measures in Bosnia-Herzegovina. A verification protocol was inspired by the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE), and in some cases even went beyond it. The treaty established a military balance of power between the countries and set upper limits for heavy weapons. The OSCE thus positioned itself at the regional level as a successful arms control agency. It might be possible to build on this model today in the Baltic States or the Black Sea – two regions that have been at the center of rearmament and military maneuvers since 2014 and could therefore benefit from CSBMs and regional arms control.

Fourth, an OSCE Document on Small Arms and Light Weapons (2000) and an OSCE Document on Stockpiles of Conventional Ammunition (2003) were adopted. Small arms, light weapons, and surplus conventional ammunition – mostly relics from the Cold War – pose a significant threat to the population, infrastructure, and environment. Among other things, these documents have helped to destroy stocks of mélange, a highly toxic rocket fuel, in Albania and Ukraine.

Fifth, the regular modernizations of the Vienna Document – in 1992, 1994, 1999, and lastly in 2011 – were also highlights of the FSC’s history. The 1990 Vienna Document is the most important CSBM in the OSCE area. The politically binding agreement provides for the exchange and verification of information on armed forces and military activities.

This brief overview shows that the FSC experienced its most dynamic phase in the first ten years after its establishment. Since 2004, similar highlights have failed to materialize. The importance of arms control diminished dramatically in the 21st century until the outbreak of the Ukrainian crisis in 2014.

War of Words in Vienna

One of the greatest problems is the deliberate political linking of arms control with totally unrelated issues. Individual OSCE participating States can thus abuse the consensus principle and the de-facto right of veto of any delegation to hijack issues such as the modernization of existing regimes. Since 1999, territorial conflicts in the Southern Caucasus have blocked the adaptation of the CFE Treaty to new realities, such as NATO’s admission of former Warsaw Pact states.

This pattern has been repeated since the outbreak of the Ukrainian Crisis, including in the FSC. The US, Canada, the UK, and other transatlantic-oriented OSCE participating States as well as Ukraine are basically unwilling to enter into any substantial negotiations with Russia until Moscow reverses the annexation of the Crimea and withdraws militarily from Eastern Ukraine. Paradoxically, however, the Ukrainian Crisis has also highlighted the need to adapt Cold War regimes to the conflicts of the 21st century. Since 2014, military issues such as doctrine developments, perceptions, and the need for verifiable transparency have been raised more frequently in the FSC and since 2017 in the OSCE’s “Structured Dialogue” on core issues of European security.

In general, the Ukraine Crisis is both a “curse and a blessing” for the OSCE, as Thomas Greminger noted back in 2014. On the one hand, the war in Ukraine has led to a “war of words” in the OSCE forums. The tone has intensified and the discussions within the “OSCE family” are increasingly tough and uncompromising. The fronts are clearly defined. Every Wednesday, the FSC discusses the Ukrainian conflict. The debates have become a ritual. First, the Ukrainian representative presents in detail all recent military incidents for which Kiev holds Russia responsible. Then the US, Canada, the UK, and the EU take the floor and signal their support for Kiev and demand that Russia should comply with the Minsk agreements, return the Crimea, and withdraw from the Donbass. The Russian representative then explains the Russian view of the conflict. This is far from the constructive dialogue the FSC experienced in the 1990s. The fronts are hardened, and it has become extremely difficult to build consensus. But the OSCE still remains the best multilateral framework for finding political solutions, where necessary. Contacts are maintained in the corridors of the Hofburg, and informal discussions are held during breaks.

On the other hand, the FSC has also experienced a kind of comeback since 2014. The variability of the FSK and the states’ interest in the forum have increased significantly. However, the OSCE – like its predecessor, the CSCE – was originally more a community of interests than values. Different values and worldviews have always clashed, and the great achievement of the OSCE has always been to find common, sustainable solutions to pressing security policy challenges in Europe by consensus.

Swiss Priorities for 2019

Switzerland is tasked with chairing 13 official meetings of the FSC between 16 January and 10 April 2019, every Wednesday morning, and to find the most constructive aspects possible on classic FSC issues (see box). Switzerland plans to use the Chairmanship to focus on six themes.

First, it devotes a security dialogue to the issue of outsourcing parts of the state monopoly on the use of force to private sector actors and related challenges. To address the growing influence of private military security companies (PMSC), Switzerland, together with the ICRC, launched an initiative in 2006 that led to the Montreux Document (2008), the first international document to provide an overview of the international legal obligations of PMSC in armed conflicts. The topic is now to be discussed more prominently in the OSCE and existing commitments, including the 1994 Code of Conduct, are to be better implemented.

Secondly, Switzerland is organizing two meetings on small arms and light weapons (SALW) and conventional ammunition – one of the few dynamic areas in the OSCE’s politico-military dimension that continues to function even in a tense geopolitical environment. The OSCE supports participating states with financial or technical assistance and expertise and implements between 10 and 20 projects each year, mostly in cooperation with OSCE field missions in Southeastern Europe, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and in the Southern Caucasus.

Thirdly, a security dialogue will address the issue of “modern warfare aspects”. Rapidly evolving technology and the resulting constantly changing doctrines of armed forces and security forces also call into question the applicability of OSCE instruments. Furthermore, the topic will be examined from an international law perspective.

Fourthly, a joint meeting of the FSC and the Permanent Council of OSCE Ambassadors was originally planned for the “Structured Dialogue” (SD) on politico-military issues launched in 2016/17. An initiative by the then German foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier to revitalize conventional arms control in Europe had, contrary to expectations and despite great skepticism on the part of both the US and Russia, led in 2017 to a “Structured Dialogue” on issues of European security in order to overcome the political blockade between Russia and the West and gradually rebuild lost confidence. In 2018, however, the momentum of the SD meetings was unfortunately somewhat lost, and it is currently unclear in what form the SD will be continued in 2019, and under whose leadership. Critical voices in the OSCE have apparently suggested that the debates on politico-military issues be transferred back from the SD to the FSC. Switzerland, on the other hand, together with countries such as Germany or Austria, prefers to continue the SD with a narrow focus on CAC. Switzerland will now dedicate the joint FSC Permanent Council meeting in February 2019 to the general topic of “European Security” – to build momentum to revive the SD under Belgium, Dutch, or German leadership.

Fifth, Switzerland wants to recall common values and principles in the Code of Conduct in order to remind the participating states of their political duties at a FSC meeting despite breaches of rules – including in particular against the background of the current weakening of the rule-based European security order. The Code of Conduct was adopted in Budapest in 1994, and it is intended that its 25th anniversary in 2019 should be an occasion for critical reflection.

Sixth, 2019 is to be the “year of SSG/R”. In a prescient measure, the topic of “Security Sector Governance and Reform” had already been codified in the 1994 Code of Conduct, even before the term became known as SSR or SSG/R respectively. The topic is also a declared focus of the Slovak OSCE Chairmanship in 2019. The OSCE lacks a strategic overview of all SSG/R-relevant activities. Switzerland will give the issue a boost by holding a joint FSC/ Council meeting together with the Slovak OSCE Chairmanship; after all, with the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) founded in 2000, Switzerland is one of the world’s leading players in the field of SSR.

Further reading

- Hans Lüber, Schweizer Vorsitz des Forums für Sicherheitskooperation der OSZE, in: ASMZ 11 (2018): 4 – 6.

- Matthias Z. Karádi, Das Forum für Sicherheitskooperation, in: OSZE-Jahrbuch (1996): 379 – 391.

- Jan Kantorczyk / Walter Schweizer, The OSCE Forum for Security Co-operation (FSC): Stocktaking and Outlook, in: OSCE Yearbook (2008): 238 – 292.

Big Expectations, Small Steps

Switzerland has traditionally enjoyed an excellent reputation in the multilateral environment of the OSCE as an active, innovative, and independent participating state, and increasingly so since the OSCE Chairmanship in 2014. The OSCE participating states therefore have high expectations for Switzerland’s FSC Chairmanship. Nevertheless, geopolitical conditions and the politicized climate at OSCE Headquarters in Vienna make it difficult even for a trustworthy Chairmanship to achieve tangible results. Existing instruments from the period immediately after the end of the Cold War, intended to create long-term confidence and security, are of little use in dealing with a “hot conflict” such as the Ukraine Crisis, where short-term results are needed. The consensus-based OSCE, including the FSC, is not made for applying far-reaching measures to create transparency. Arms control and CSBMs in general, including outside the OSCE, are increasingly being held hostage by realpolitik and are losing importance.

In this sense, the FSC Chairmanship of Switzerland in 2019 should not be expected to produce miracles. But small steps to improve mutual trust between Russia and the West and new constructive impulses to reduce military risks and the future of conventional arms control in Europe are already valuable achievements today. Certain objectives of the Swiss FSC Chairmanship are deliberately aimed at geopolitically uncontroversial topics such as small arms. Switzerland’s commitment to peace and security in Europe and better implementation of OSCE commitments is a good example of an engaged, independent foreign policy.

About the Author

Dr. Christian Nünlist is Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. He is author of, among others, Reviving Dialogue and Trust in the OSCE in 2018 (2017) and external pageNeutrality for Peace: Switzerland’s Independent Foreign Policycall_made (2017).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.