Youth Bulges, Exclusion and Instability: The Role of Youth in the Arab Spring

31 May 2016

By Kari Paasonen and Henrik Urdal for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pagePeace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)call_made in Conflict Trends 03/2016.

Large ‘youth bulges’ increase the risk of democracies collapsing and armed conflicts breaking out. Responding to this perceived political threat, governments’ response may be to increase repression. And it is in the context of large youth bulges that the ‘Arab Spring’ occurred with those participating in protests being the youngest and the most educated. While the Middle East and North Africa are rapidly maturing demographically, low economic and political opportunities for the youth in the region remain a major concern.

Brief Points

- Youth bulges are associated with conflict and instability, but could be a major economic resource.

- The well-educated and the youth at large were more likely to take part in the Arab Spring protests, while the unemployed were least likely.

- The demographic pressure is declining across the Middle East and North Africa, but major challenges remain.

Youth, Instability, and Conflict

When countries undergo rapid demographic change as a result of declining mortality, the result is often large youth cohorts, or ’youth bulges’. Youth bulges have historically been associated with times of political crisis, and recent PRIO research finds that the statistical risk of conflict is increased in countries with very young populations.

Youth bulges provide rebel organizations with a steady supply of potential recruits. The cost of recruiting a young person is low to begin with, and labor markets are often unable to absorb a sudden influx of young job-seekers, leading to higher youth unemployment. A large pool of frustrated, unemployed young people therefore makes for fertile ground for rebel recruiters.

Similarly, when large groups of youth aspiring to political positions are excluded from participation in the political process, they may engage in violent conflict in an attempt to force the government to democratize. Yet, young populations also pose a challenge to stabilizing democratic governance. New research shows that youth bulges are associated with regime change more generally, and also that they increase the likelihood of democracies being toppled.

Governments are unlikely to be passive bystanders to the challenge posed by youth, but policies differ. While states may pursue strategies such as expanding education and facilitating youth in the labor market, recent PRIO research shows that many states facing the challenge presented by youth bulges, increase their levels of repression in an assumed attempt to quell the threat that these large youth groups pose to national stability.

Education

Education can arguably be a double-edged sword as a policy to contain youth bulges. By expanding education, expectations grow among large youth groups, potentially backfiring if states cannot deliver employment opportunities when the youth graduate. In the absence of jobs, massive discontent could arise among a young population increasingly easy to mobilize.

However, while discontent among highly educated youth could increase anti-government protests, increasing levels of education is generally associated with a strong decline in the risk of armed conflict. In most societies, increasing education offers better economic prospects and reduces the proportion of youth who may be recruited to violence. This is particularly the case if education is provided universally, and thereby contributes to reducing social inequality.

Large youth bulges may be a blessing rather than a curse if the labor force potential is realized. In the Asian Tiger economies such as South Korea and Taiwan, around a third of the economic growth was due to the favourable demographic conditions. The ability of states to take advantage of this demographic bonus’, however, depends chiefly on skills and education, on declining fertility (which reduces the need for investment in children), and on investments in labor-intensive sectors that create a job market. While many countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are increasingly well positioned demographically, significant challenges remain with respect to human capital and the labor market.

Youth and the Arab Spring

When vegetable vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in a Tunisian provincial town in December 2010, he started a protest which quickly spread to Tunis and elsewhere in the country. Eventually it led to the unseating of President Ben Ali, who had ruled Tunisia for twenty-three years, in January 2011. Protests soon erupted in other countries and during 2011 the Arab Spring, the wave of demonstrations and uprisings, affected large parts of North Africa and the Middle East. In Libya and Syria full-scale civil wars broke out, the governments of Egypt and Yemen were toppled, and major protests took place across the region.

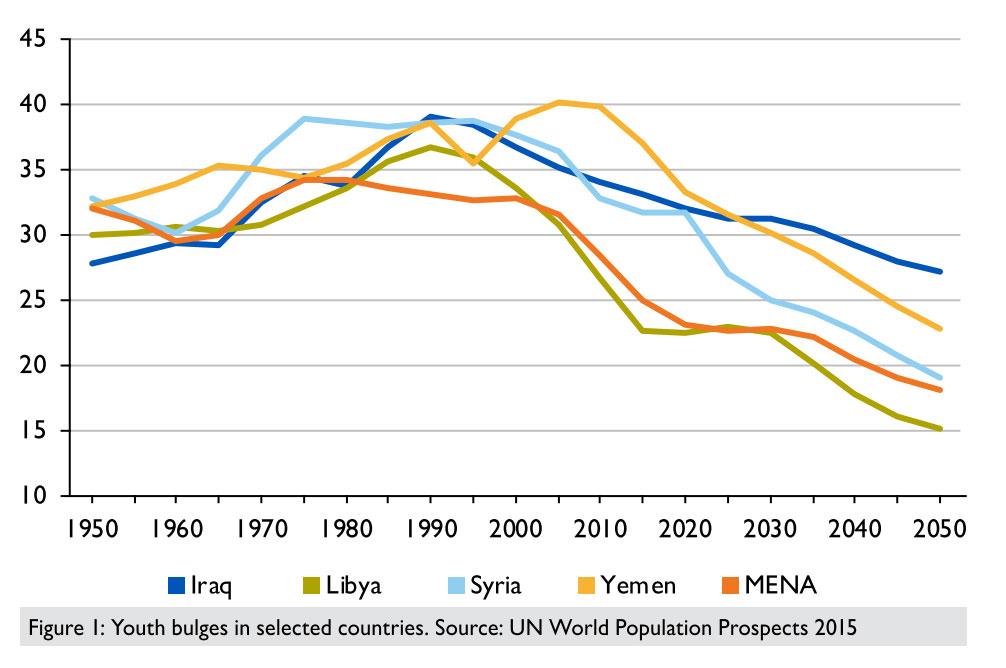

This policy brief addresses three key demographic and social factors frequently invoked as structural causes leading to the Arab Spring: youth bulges, unemployment, and education. In the Middle East and North Africa, many countries have had very youthful populations until recently, with those between the ages of 15 and 24 making up more than 30% of the population aged 15 years and above. Yemen, Syria and Iraq were among the countries with the largest youth bulges preceding the Arab Spring (Figure 1). The projection suggests that some of the most conflict-prone areas, including Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Palestine, will continue to be youthful, but that in many other key countries in the region, notably Tunisia, Iran, Turkey, and Lebanon, and later Egypt and Saudi Arabia, the pro-portion of youth in the population will decline more rapidly. These demographic shifts in the MENA region also positions a number of countries for a demographic bonus, notably Iran, Turkey, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon.

Limited economic opportunities and a preference for public sector employment have caused large groups of youth to enter the labor market later and delay marriage and the creation of families, a situation often referred to as ’waithood’. In addition, those highly educated living in the Arab world are suffering from unemployment as much if not more than people with less education. This is an exceptional situation in the world as education generally enhances employment opportunities. Figures from the International Labour Organization (ILO) show that unemployment in the Arab world, and particularly youth unemployment, is substantially higher than the world average. The variation across the region is significant.

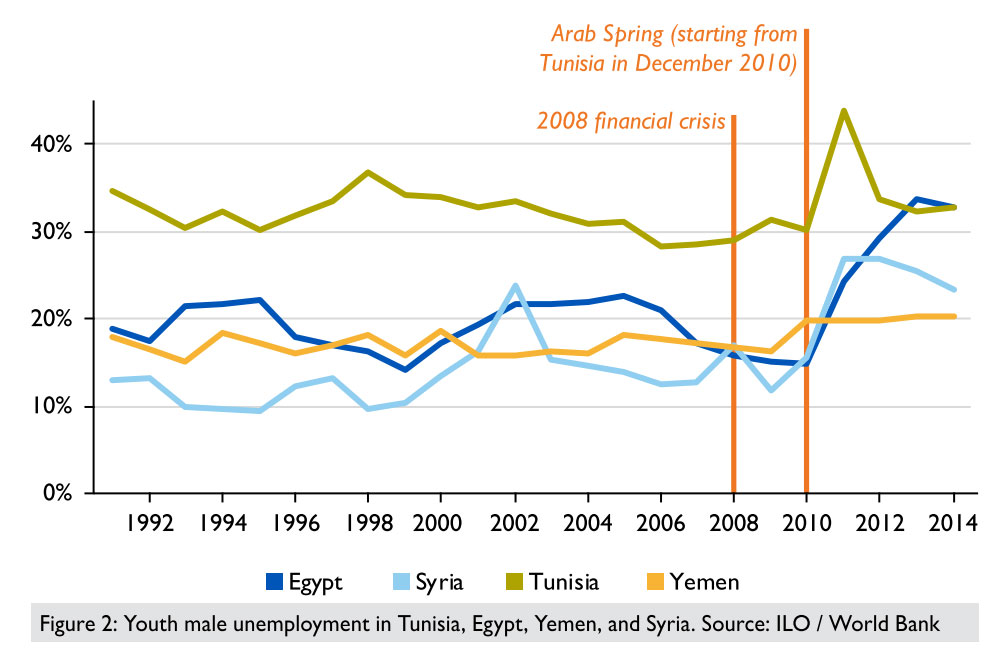

While some of the oil producing countries in the Gulf have experienced low unemployment and attracted labor from the whole region, youth unemployment in Tunisia has fluctuated around 30% for the past couple of decades.

The 2008 financial crisis caused a considerable increase in unemployment in the European Union. The Arab countries as a whole, however, did not see this increase after 2008. In fact, in 2010, on the eve of the Arab Spring, unemployment rates in the Arab countries were on average at their lowest level since 1991. And while unemployment is undisputedly high across most Arab countries, no Arab country has since 2011, had a recorded youth unemployment rate higher than that of Spain, according to ILO.

Figure 2 displays youth male unemployment rates in four countries which were hard hit by the Arab Spring: Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Syria. Unemployment did not increase significantly in Tunisia nor did it in Egypt in the years preceding the Arab Spring. In Syria and Yemen, there were minor upticks in unemployment, but no major shift. However, from 2010 to 2011 the unemployment rate rose sharply both in Egypt, Syria and Tunisia in response to the Arab Spring.

Who Participated in the Arab Spring?

The third wave of the Arab Barometer, which we use here, was conducted between December 2012 and April 2014. In total around 15,000 respondents from twelve Arab countries were asked whether they in 2011 and 2012 had participated in demonstrations and rallies associated with the Arab Spring. The countries included Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen. Due to the ongoing civil war, Syria was not included. Here we separate between two samples. The first consists of four of the countries which were most strongly affected by the Arab Spring: Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. The second sample consists of the remaining countries.

Levels of reported participation vary significantly. In Yemen 42% of all respondents reported to have participated in the Arab Spring protests. Corresponding rates were 33% in Libya, 19% in Tunisia, and 14% in Egypt. In the remaining countries between 3 and 15% of respondents reported that they had taken part in the Arab Spring demonstrations and rallies in their country. Earlier, the World Barometer Survey conducted in the years 2001–2006 had shown that respondents from the Arab States were generally more active in protesting and demonstrating already before the Arab Spring compared to other major developing regions.

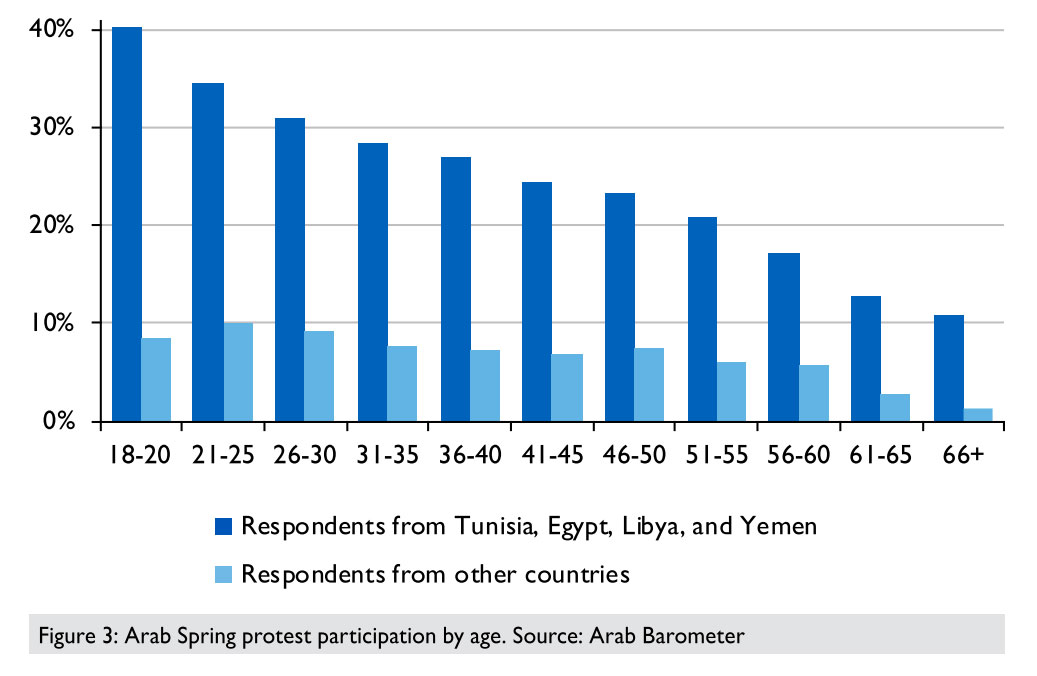

Figure 3 illustrates the importance of age. Across the four main protest countries, among youth aged 18–20, 40% reported to having participated in demonstrations. For all age groups between 18 and 30 years, more than 30% had participated. The data also shows that participation increased dramatically by education. And indeed, while about 16% of those with no formal education participated in demonstrations, 32% of respondents with secondary education and 36% with higher education had participated.

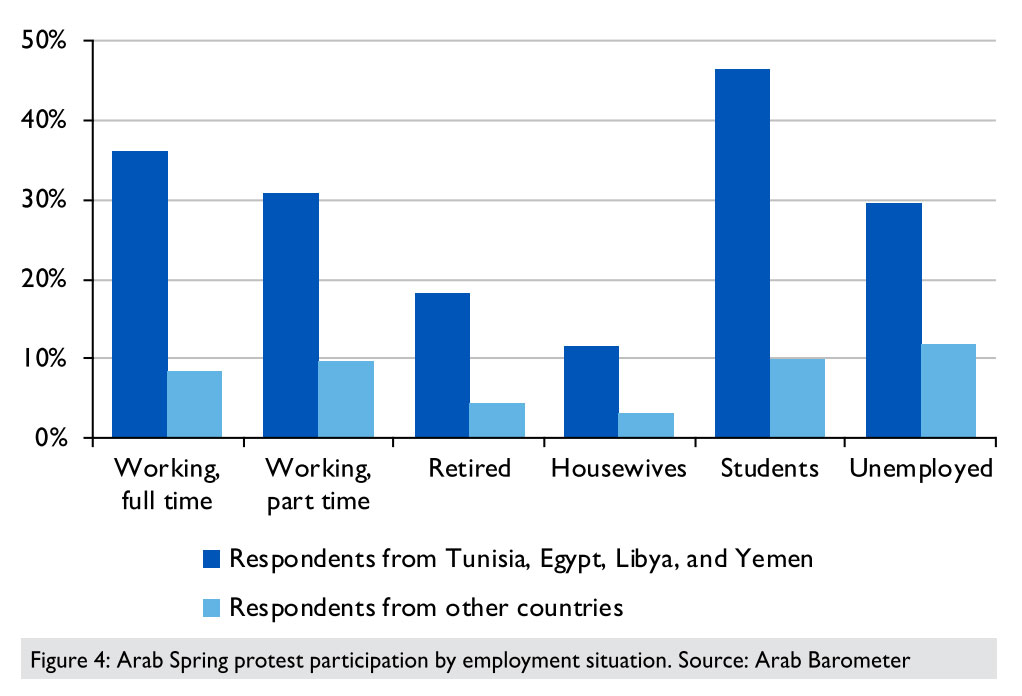

The unemployed were not particularly active in the demonstrations in the four most affected countries (Figure 4). Rather, participation was highest among students and among people who were already employed. Students were particularly active in demonstrations in Egypt and Tunisia. It seems therefore that the Arab Spring was not primarily a revolution of the poor and deprived as indeed the vast majority of those participating were relatively well educated and employed or in school. Alternative data sets confirm these conclusions.

Implications for Future Stability

For most countries in the Middle East and North Africa, the demographic situation will become easier to handle as the large youth bulges decline. The countries that will continue to face the greatest demographic challenges, however, are exactly the countries that currently experience the greatest levels of violence and instability: Yemen, Iraq, Palestine, and Syria. A particular demographic phenomenon is, however, going to hit many states in the region over the next two decades, namely youth ‘echo booms’.

These are strong increases in youth populations simply due to the large cohorts of their parents. Countries like Iran, Libya, Algeria, Egypt and Tunisia will go from experiencing a decline in the absolute numbers of youth, as they currently are, to experiencing increases of as much as 10–20% per five-year period around 2025–2035.

Initiatives to expand education in the MENA region have resulted in relatively high levels of secondary education, with enrolment rates above 80% in most countries. Notable exceptions are Iraq and Yemen, with overall secondary enrolment rates of around 40% and significantly lower rates for girls than for boys. Important concerns have also been raised with respect to the quality of schooling. International surveys of student knowledge in mathematics and science suggest that MENA students on average are far below the international standard.

Despite recurring concerns, the prospects of seeing a declining risk of conflict from current levels are certainly present. The most likely scenario is perhaps an even more pronounced two-tier development where the demographically and socially advancing countries will have the best prospects for long-term stabilization. Given this expected development, a recent conflict prediction project at PRIO expects the Middle East and North Africa to experience the strongest future decline in conflict, from 27% of countries in conflict in 2009 to an estimated 6.2% in 2050.

About the Authors

Kari Paasonen is a visiting student at PRIO and Henrik Urdal is a research professor and an editor of the Journal of Peace Research at PRIO.