Swiss Border Guard and Police: Trained for an ´Emergency´?

19 Oct 2016

By Lisa Wildi for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center Security Studies (CSS) in the Analyses in Security Policy series in October 2016.

In autumn of 2015, the German Federal Police (“Bundespolizei”, the former Federal Border Guard or “Bundesgrenzschutz”) reached its limits. They were no longer capable of controlling, transporting and registering the arriving asylum-seekers on their own. In the course of the crisis, there were recurring debates over which government authority was to take on which tasks. In Switzerland, too, parliament has repeatedly discussed since last autumn which forces should support the SBG in the case of an acute crisis. Under the “Asylum Contingency Plan” approved by the Federal Administration, cantons, cities, and communities in April 2016, the SBG corps would be supplemented by cantonal police forces and, should these not suffice, by soldiers. However, the usual areas of responsibility are to be preserved as far as possible in the case of a “refugee contingency”.

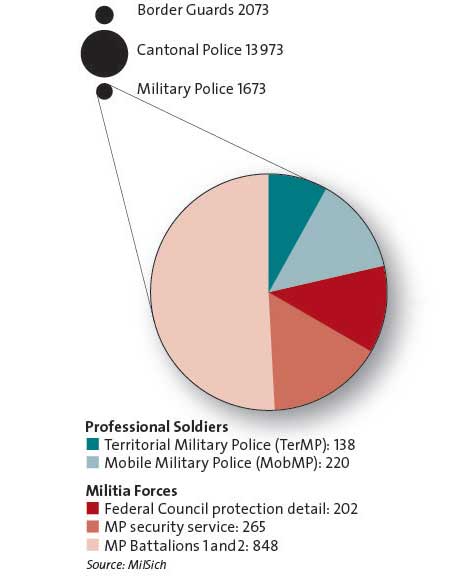

Should the SBG require support, the Federal Department of Finance (FDF), of which the SBG is a part, would request police reinforcements – initially from the canton in which assistance is required. Should this measure prove insufficient, the FDF and the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS) would submit an application to the Federal Council for support by military forces. The Federal Council would then decide on the deployment of soldiers and assign troops to the SBG. Initially, it is anticipated, the SBG would be supplemented with professional soldiers from the military police force. Their job would be to protect the border guards or to assist them at border checkpoints. If this support is insufficient, militia forces would be deployed, for instance for monitoring and blocking individual sections of the border. If the auxiliary deployment of the armed forces lasts more than three weeks or requires more than 2000 troops, parliament would have to approve the deployment at its next session In the case of a crisis involving refugees, moreover, the DDPS would also support the SBG and the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) with troops and material in the areas of medical services, construction, logistics, and transportation. The army would continue to assist the SEM in identifying and providing shelter for asylum seekers.

Regarding the reinforcement of the SBG corps, a number of critics have warned that the police and the military police can only support but not replace border guards, since their training does not correspond to that of the border guard. However, their respective training programs are very similar. The question arises, therefore, what kind of border policing tasks would even be required during an “asylum contingency” and to which extent (military) police and border guards are trained to handle these tasks, including the cooperation this would require. In the following, we will look at the so-called “refugee crisis” that Germany experienced in 2015 to establish which tasks were carried out by the Federal Police, the state police forces, and the Bundeswehr (armed forces). The subsequent section will focus on training and cooperation of Swiss (military) police and border guards.

The “Refugee Crisis” in Germany

In Germany, the Federal Police are responsible for border protection and controlling arrivals. During the so-called “refugee crisis” of autumn 2015, their main tasks were: screening arrivals at the border crossings, organizing the crowd upon arrival, ensuring order and safety, recording personal data and fingerprints, cross-checking data with databases, issuing temporary documents, and transporting asylum-seekers to initial accommodation. Another aspect of everyday work was to identify and arrest those who assisted the refugees in entering the country.

Due to the large number of refugees arriving, the Federal Police were temporarily overstretched in some of the German states. Officers put in countless hours of overtime and reached their limits of endurance. First, Federal Police officers were called in from neighboring federal states to assist them. Armed law-enforcement agents of the German customs authority were also deployed. State police supported them, for instance by organizing transportation for the refugees, registering refugees, or finding accommodation. Furthermore, they provided protection for the refugees in the arrival centers.

Several state governments offered extensive support to the federal government. For instance, the Bavarian government offered the assistance of Bavarian police officers to the Federal Police along the border. However, due to jurisdictional rules, this offer was turned down. For the same reason, no Bundeswehr soldiers or military police were involved in policing the border crossings or in domestic security measures. These tasks are the prerogative of the federal and state police forces. However, soldiers did assist with construction of refugee housing and registering asylum-seekers.

The civil protection services, which include the fire brigade, the Technisches Hilfswerk (Federal Agency for Technical Relief), the Red Cross, and other relief organizations, took responsibility for preliminary medical services, and provided food and clothing. A great number of volunteers supported the relief efforts.

Switzerland: Existing Cooperation

In Switzerland, although the SBG and the military police (Militärische Sicherheit, Mil Sich) and the SBG and the police cooperate during everyday work, collaboration is not part of their basic training. Under the Federal Constitution, the armed forces may give support to the civilian authorities in warding off significant threats to internal security and managing other exceptional situations. Under the Military Act, the army can extend support if requested by the civilian authorities. Inter alia, soldiers may be deployed for the protection of individuals and certain installations which are in need of special safeguard, for managing disasters, and for the fulfillment of other tasks of national significance. Support is given in accordance with the subsidiary principle, i.e., only if the civilian authorities are no longer able to handle the tasks entrusted to their responsibility.

Until a few years ago, the professional unit of the military police had carried out a subsidiary protection mission for the SBG corps. This subsidiary support mission, codenamed LITHOS, was due to the security situation and the SBG’s lack of own assets. It lasted from 1997 to 2012. For 16 years, a daily average of 84 military police officers served on behalf of the SBG. Under the “Ordinance on troop deployments in support of the border police” (Verordnung über den Truppeneinsatz für den Grenzpolizeidienst, VGD), military forces, including military police, may carry out three types of tasks at the frontier: monitoring the border, protecting border guards and police officers at border checkpoints and in the open country, and similar comparable tasks. The ordinance also stipulates that military forces may only be deployed to the frontier for the kinds of tasks for which they are trained.

Cooperation between the SBG corps and the cantonal police forces has also been intense in recent years. It has been governed by cooperation agreements, which were prompted by the expansion and transformation of the SBG’s tasks in recent years due to Switzerland’s accession to the Schengen/Dublin Agreement in 2008. Ever since, the border guards have been active not just at the immediate border, but also in the rear areas further inland, necessitating arrangements and coordination with local police forces. In everyday life, cooperation between police officers and border guards has become a matter of routine. The SBG frequently supports the cantonal police forces in border regions. Today, border guards carry out traffic controls and administer breathalyzer tests, check compliance with work and rest period regulations, and secure crime or accident scenes in cases of burglary, domestic violence, or car crash. Moreover, the professional military police units also extend sporadic support to the SBG and the cantonal police corps for traffic control or identity checks. Under a new draft of the military law, they would be permitted to give ad-hoc assistance to civilian police and the SBG corps.

The intense cooperation between police and border guards and the similarities in their everyday work are also illustrated by the latest research, soon to be published in the “2016 Bulletin on Swiss Security Policy”. Cantonal police officers and border guards already cooperate quite closely compared to other official state institutions in the field of security policy; the threats they combat are largely identical. Petty crime, violence against life and limb, traffic violations, and migration-related problems are of equal concern to the police and the border guards. However, in addition to these challenges, border guards also deal with terrorism, human trafficking, arms trade, and money laundering. For the cantonal police forces, hooliganism poses an additional challenge.

Training of Police and Border Guards

A comparison of professional trainings can be restricted to training of the police and border guard, since those members of the military police who handle traditional police tasks within the military – i.e., the members of the Territorial Military Police (TerMP) – have undergone the same civilian police training course since 2010. Moreover, TerMP members who were trained pre-2010 have since also passed their professional examination as police officers. This allows them to transfer to a civilian police force. Members of the Mobile Military Police (MobMP) force, who are trained as security specialists within the armed forces, will not be taken into consideration in the following. The SDBR and SDMP militia units, which would be activated in case of war, consist mainly of civilian police officers willing to serve in the military in this format, even though they are not subject to conscription as members of the police. Conversely, Military Police Battalions 1 and 2 include only few civilian police officers (cf. illustration, p. 2).

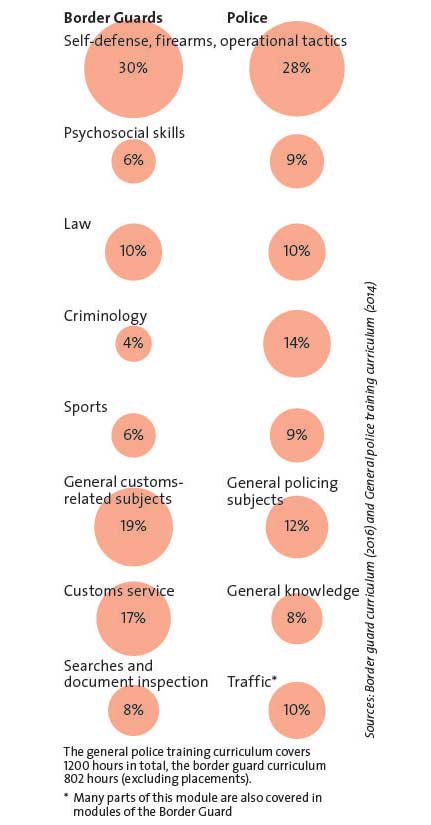

Basic training is very similar for the police force and the border guards, both in terms of substance and structurally, and both impart skills that would be applicable in case of an “asylum contingency”. For instance, in both cases, trainees are taught how to carry out identity checks, how to demand papers, how to search people for dangerous items, or how to control large crowds. Furthermore, police officers and border guards learn about self-defense and the use of force in case of need. Their respective trainings for policing, self-defense, and weapons handling are nearly identical. Police officers and border guards trainees alike learn to handle firearms and batons, how to arrest people, or how to apply joint operational tactics.

Trainees are also taught how to react appropriately in crisis or conflict situations, how to communicate in a manner that is appropriate for the situation, or how to deal with stress. Ethics and human rights are also on the curriculum for both forces, often to the point of identical instruction material for subjects related to policing and psychosocial interventions. However, the duration of training for the various subject areas varies to some extent (cf. illustration, p. 3). For example, a police officer receives more extensive training in psychology than a border guard because police officers will be confronted more frequently with human drama and interpersonal conflicts in their everyday work. In matters of community policing (CP), which emphasizes social and communication skills, border guard training is similarly lacking depth. Any police officer, on the other hand, will have had extensive training in CP theory and studied concrete measures for winning the trust of the public and thus preventing crime and accidents together.

Administrative work, such as registering people or issuing official documents, is a routine matter for police and border guards. Among other topics, their training includes reporting, where they learn how to register personal data and write up incident reports. Even in the entrance examinations, language skills in the native tongue are rated very highly. These skills are further fostered in police academies. However, foreign languages that would be of great help in dealing with refugees are not taught – neither at the police academies nor at the SBG training center. One exception is English teaching at the Zurich Police School. For border guards, on the other hand, it is customary to learn a foreign language after their basic training, through in-house language courses and exchange programs.

Other concerns shared by police and border guard training alike are in the area of legal instruction. Both the police cadets and the trainees of the SBG attend lectures on criminal law, the code of criminal procedure, traffic law, and laws on firearms or foreign nationals. However, border guards receive more comprehensive instruction in the latter. Police and border guards also acquire legal expertise that is specific to their respective areas of work. Police cadets, for example, study the requirements for the use of coercive measures by the police, as well as alcohol legislation or the Swiss Environmental Protection Act. Meanwhile, border guards trainees deal with matters pertaining to customs and excise legislation, such as assessment procedure, customs ordinances, or transport levies. Other matters of specific relevance to the border guards are inspection of documents, international search and arrest warrants, and general customs-related studies such as the Schengen/Dublin Agreement, the procedure of asylum cases, and the granting of residence permits. A border guard will therefore be familiar with entry requirements, readmission agreements, or policing treaties with neighboring countries. Unlike a police officer, a border guard will be able to assess whether a given person is authorized to enter the country or not.

Structurally, basic training lasts one year for both groups, concluded by a federal diploma examination. The curricula include not only lifelike training units and theoretical instruction, but also trainee placement with the duty forces. For the border guard, basic training is followed by two years of mandatory further education in matters related to customs, document inspection, criminology, operational tactics, providing security, and search and rescue operations. During these first two years after completing their basic training, border guards work in two of three future work environments (mobile forces, rail, airport).In police forces, too, it is customary for novices to be sent to different stations for introductory programs or trainee placements. Similarly, military police officers are familiarized with the organization, rules, and regulations as well as the equipment of their corps over several months of training. However, police officers do not receive three years of training like their colleagues in the SBG.

Beyond the similarities and subtle differences regarding the content and structure of basic training, it is remarkable how both police and border guard officers share a similar esprit de corps as well as similar ideas about how security is (re-)established and maintained. However, due to the many differences between their respective mandates, they have different conceptions about their tasks. Border guards regard themselves as “hunters” seeking out persons who have violated customs or immigration law. Police officers, on the other hand, will rather regard themselves as “problem solvers” who are notified about violations of laws and emergencies or come across them on patrols, and whose job it is to register or to sanction such incidents or to help those afflicted.

Possibilities and Limitations

Both police and border guards are trained for the challenges of a “refugee crisis” and have the necessary experience in cooperation. Theoretically, with the training they have received, police officers and members of the TerMP would even be capable of supporting the SBG in more areas than currently anticipated; for instance, in upholding public order, registration, or initial psychological assistance to asylum-seekers. The common denominators of security provision, conflict and crisis management, the legal foundations, and the shared understanding of how security is established and maintained provide opportunities for close cooperation. In practice, the cantonal police forces and especially the TerMP would soon run out of sufficient personnel to take on all the duties described or to extend long-term support to the SBG. Officers cooperating with the SBG along the frontier will be absent elsewhere. Moreover, (military) police officers lack the customs- specific knowledge about entry permits and asylum processes and would require further training in these areas. Also, in Switzerland as in Germany, many jurisdictional matters and tasks are set in legislation. For instance, the armed forces are subject to an ordinance setting out the tasks that military forces, including the military police, may carry out at the border. This means that a police officer or member of the TerMP, due to legal restrictions and lack of border-specific training, would indeed not be able to take on all the duties of a border guard, and vice versa. However, due to the existing similarities in their training and their frequent collaboration in many areas, (military) police officers would be able to support the SBG corps in an emergency situation.

About the Author

Lisa Wildi is a researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. Among other publications, she is the co-author of Vom Landjäger zum modernen Ordnungshüter: Die Polizeiausbildung in der Schweiz (forthcoming).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.