More Continuity than Change in the Congo

11 Feb 2019

By Larissa Jäger and Benno Zogg for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published in the CSS Analyses in Security Policy Series by the Center for Security Studies on 6 February 2019. It is also available in French and German.

The importance of promoting stability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) for the region can hardly be over stated. Situated in the heart of Central Af rica, the DRC has an estimated population of 80 million and its surface area equates to two thirds of Western Europe. Ethnic ties, illicit economic activities and armed groups frequently cross borders, thus creating spillover effects. Yet the DRC faces chal lenges beyond the well-known issues of violence, state failure and resource mis management. It is thus crucially important to analyze not just the recent election re sults, but also scrutinize the political sys tem itself and explore how political power is exercised. There are economic and politi cal roots of violence that cannot be ignored: poverty, underdevelopment, land disputes, misinformed government policies and in ternational interventions. The endemic corruption and infighting within the elite further undermine the enormous potential of the fertile and resource-abundant state.

Between 1997 and 2003, the first and sec ond Congo War claimed the lives of up to five million people, in what was possibly the largest manmade disaster of the last few decades. This included casualties from the continuation of the Rwandan genocide of 1994 on Congolese territory involving the new Rwandan army, their Congolese allies and génocidaires. Insecurity remains widespread in the DRC even today; up to 120 rebel groups are still active in the East ern provinces. The violence is barely con tained, and only through the efforts of the often ruthless Congolese army and the largest United Nations peacekeeping mis sion, MONUSCO.

Both domestically and internationally, hopes were high that free and fair elections could usher in a new era of peace and stabil ity. On 30 December 2018, the DRC elect ed a new president. The outgoing president, Joseph Kabila, was constitutionally barred from serving a third term. He had post poned the elections originally scheduled for 2016, and managed to exclude political ri vals from the elections under false pretens es. When elections did finally take place, over a million people (predominantly from the Eastern provinces) were unable to cast their votes due to a recent Ebola outbreak. Coincidentally, these constituencies also tend to strongly support the opposition.

Despite an internet shutdown, multiple al legations of manipulation and glaring lo gistical difficulties, the election commis sion declared opposition candidate Félix Tshisekedi the victor by a small margin. Kabila had initially supported his rather plain Interior Minister Emmanuel Sha dary in the presidential race, in an attempt to guarantee his security and prosperity af ter leaving the presidency. Yet Tshisekedi’s ascendency does not appear to pose a threat to Kabila moving forward. Tshisekedi has little political experience and a small power base, and is therefore reliant on the support of elites close to Kabila. Accordingly, Kabi la likely considers Tshisekedi as the lesser of two evils compared to the second oppo sition candidate Martin Fayulu, who was supported by Kabila’s most important ri vals and whom independent observers from the Catholic Church identified as the clear winner.

The significance of the transition of power in the complex political landscape of the DRC – and the international reactions to it – will only become fully apparent in the medium term. Kabila declared he will re main present in the political scene. The ma nipulation of elections and the largely un altered political elite further suggest that there will be more continuity than tangible change. A critical component of the DRC’s ability to stay the course is China’s growing role as an alternative economic partner to European governments and companies. In a similar fashion as in other parts of Africa, China invests mainly in mining and infra structure and has recently become the DRC’s largest trading partner. Further more, China emphasizes its political non-interference and is interested in stability.

Colonialism, Kleptocracy, Congo Wars

The current instability in the DRC reflects a turbulent recent history. The kingdoms that had existed for centuries on the terri tory of the present-day DRC were eroded by Portuguese influence, slave trade and Belgian colonial rule. During the rule of Belgian King Leopold II, the predatory ex ploitation of the land and its people claimed the lives of more than ten million Congolese. Having started with rubber, the beginning of the 20th century saw the Bel gians increasingly mining copper, gold and uranium deposits. The DR Congo achieved formal independence in 1960, but the sep aration process was rushed and the new country arguably ill-prepared for governance over such a large and populous state. Patrice Lu mumba was elected as the first president, though he was quick ly ousted in a military coup by Army Colonel Mobutu Sese Seko, who en joyed support from Western powers. In the following decades, Mobutu manipulated both the extraction of natural resources as well as state functions to serve his personal enrichment and to consolidate his power.

Due to the DRC’s colonial heritage and Mobutu’s legacy, poverty and conflict persist to this day. The Belgian practice of ruling through local elites, usually recruited from specific ethnic groups, has a particularly long-lasting legacy of damage. During Bel gian rule, access to positions of power and opportunities in the economy and educa tion were concentrated to those privileged ethnicities, who therefore succeeded in se curing land ownership in the independent Congo. Furthermore, the exploitation of lo cal people resulted in the depopulation of entire swathes of land and the Belgians ob tained workers for their plantations by forc ing Rwandans to migrate into the Congo. It was through these violent and drastic de mographic shifts that ethnic divisions in the DRC were strengthened and politicized.

An external shock in 1994 further exacer bated the growing ethnic tensions through out the country. As hundreds of thousands of people fled to the Congo due to geno cides in neighboring Rwanda and Burundi, the DRC also experienced a spill-over of the Rwandan genocide on its own territory – with lasting consequences. The new Rwandan government began to support Congolese rebel groups loyal to them, with the aim of persecuting suspected génocid aires taking refuge in the DRC. Even today, Rwanda continues to exercise significant political and economic influence in the eastern DRC.

At least eight African states participated in the bloody conflicts, collectively called “Af rica’s World War”, between 1997 and 2003. Over the course of the wars, rebel leader Laurent Kabila was able to assert himself as Mobutu’s successor. In exchange for their support, he provided his allies with mining licenses or natural resources. He was assassinated in 2001, and his son Jo seph succeeded him in office. Joseph Kabila was elected president in 2006 and re-elect ed in 2011, but while the first elections had in large part been free, the re-election in 2011 was manipulated and marred by vio lence. Kabila had failed to live up to his promises as leader and had lost popularity among the Congolese people.

The Political System of the Congo

Periods of function and dysfunction in the Congolese state closely follow these his torical developments. Western notions of corruption, state, democracy and opposi tion become blurred in the case of the DRC. While the usual focus both in inter national politics and academia is on state failure and insecurity in Eastern Congo, the ways in which statehood is actually ex ercised throughout the entire country are often neglected. In the capital, the repres sive arm of the state apparatus is strong and professionalized. The army is largely under government control. As absent as the state may seem in some areas, even the most re mote places are integrated into complex political networks linking local, provincial and national levels. The exercise of political clout must therefore be seen as dynamic and constantly (re-)negotiated, rather than a monolithic formalized state apparatus. Power is only loosely tied to office and is evident more as a combination of formal and informal structures, in a system known as neopatrimonialism.

Power, funds, lucrative offices and territo rial control are distributed in this system, resulting in the mass exploitation of raw materials and the local populations. Neigh boring countries engage in these practices, most notably Rwanda and Uganda. As a direct consequence of these networks, the Congolese army, non-state armed groups, politicians, as well as formal and traditional leaders alternate between symbiosis and conflict with each other, often over short spans of time.

Seeing as members of the army and other state representatives are hardly ever paid, they finance themselves through an array of predatory practices. Yet these non-West ern governing structures have unintended positive consequences for the stability of the nation; corruption replaces the salaries of soldiers and other state representatives, and so in a way ensures the continuation of a functioning state and the provision of a minimum of goods and services.

Kabila has long been at the heart of these neopatrimonial networks, and he will likely attempt to manipulate them to ensure his continued security and prosperity. He has kept the country reasonably stable and pre vented a violent change of government, but has always primarily been motivated by self-enrichment and the maintenance of power. The Congolese people exert a tan gible, though limited, influence over gov ernmental decision-making through pro tests on the streets, but otherwise have little impact in the nominally democratic Democratic Republic of the Congo. With the exception of the widely respected Catholic Church, state repression renders the marginalized civil society and press to positions of limited influence as well.

Since 2006, a decentralization reform has been underway in the DRC. The course of this initiative is reflective of the Congolese political system as a whole. In the eyes of Western partners, including Switzerland, the term decentralization implies policies that are close to the people and, ideally, more accountable and transparent. In the DRC, however, the existing 11 provinces were divided into 26, and along lines that fragmented political elites and the power base of Kabila’s rivals. The reforms prom ised a distribution of 40 percent of state revenues among the provincial administra tions. Instead, state revenues have gone pri marily to the national presidential admin istration. Provinces, meanwhile, make up funding shortfalls by implementing new taxes and fees, largely at the expense of the population. The province of Bas-Congo, for example, introduced a tax on school fees, without actually being responsible for the education system, and taxes on waste disposal, although no such service exists. The provinces, ironically, are using the de centralization reform to centralize power and finances for themselves. Provincial budgets are, in turn, primarily spent on the salaries of senior civil servants, thus repro ducing the existing neopatrimonial system in multiple levels of society. In the absence of an independent judiciary and given the repression of the free press and manipulat ed elections, the system remains far from being citizen-centric and transparent.

The DR Congo and Switzerland

The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) currently has some 10 million Francs per year at its disposal for the DRC as part of its focus region around the Great Lakes. Switzerland’s priorities are health and water supply in Eastern Congo, and support for victims of sexual and psychological violence. In the province of South Kivu, the SDC is seeking to strengthen governance and legal security around land ownership and to resolve land conflicts through mediation. As such, their operations seek to address a political issue that is a fundamental aspect of social tension and resulting violent conflicts in the DRC.

Switzerland has responded to recent crises with funds for humanitarian aid, notably to combat the Ebola epidemic in Eastern Congo since 2018 and to stabilize the regions of Katanga and Kasai after outbreaks of violence (in 2016 and 2017 respectively). At the diplomatic level, Switzerland is trying to promote dialogue-based approaches, both within the framework of international missions and locally. As a military contribu tion, four staff officers are deployed to the UN mission MONUSCO. As part of an international initiative, Switzerland cancelled all debts of the DRC in 2003.

As the hub of international commodity trade, some companies based in Switzerland have working relationships with the DRC, some of which are problematic. Many companies use subsidiaries to legally avoid paying local taxes. Mining licenses are often acquired in opaque processes and below market value. These practices massively deprive the Congolese state of revenue.

Land and Natural Resources

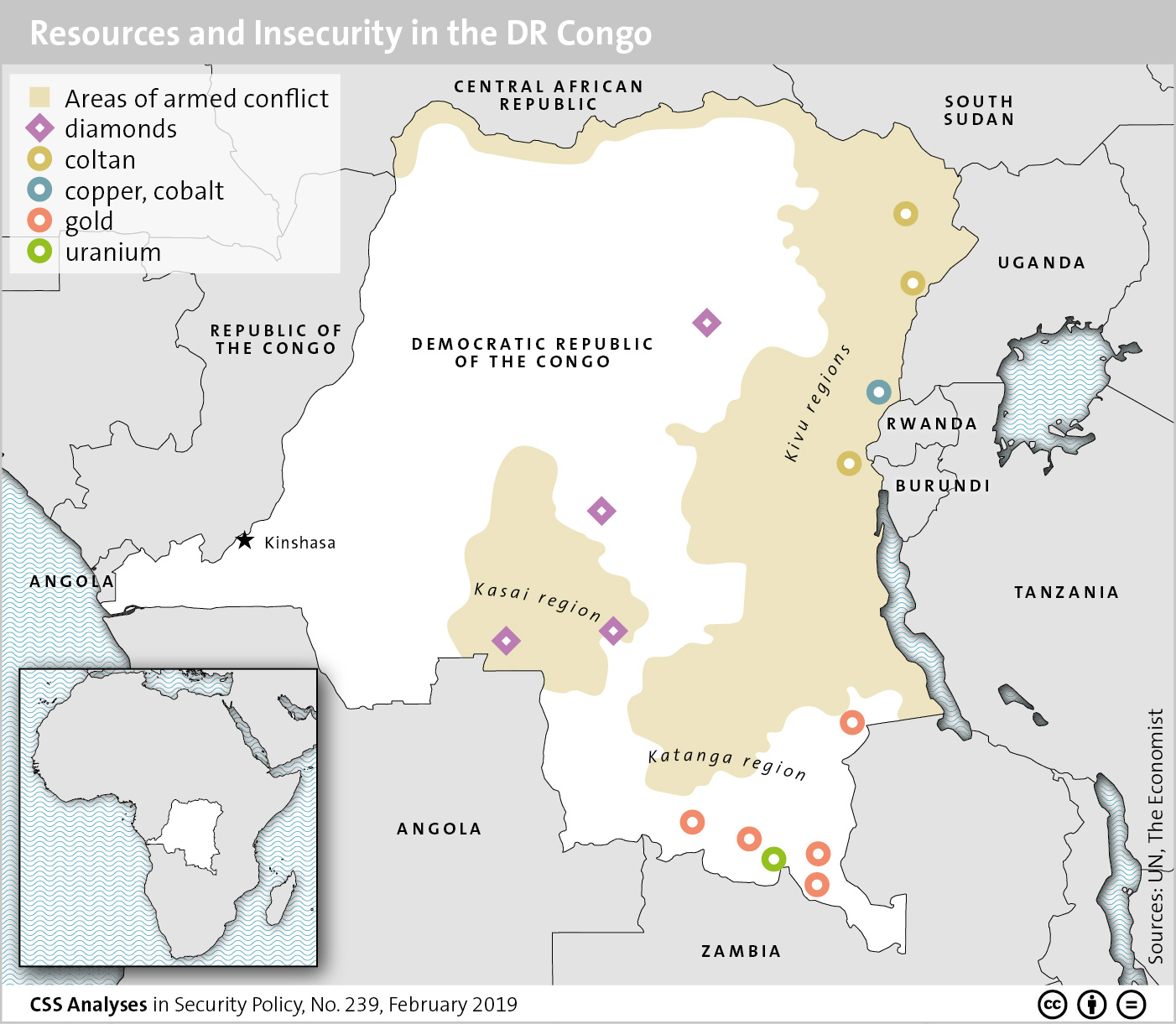

These political obstacles cloud the eco nomic potential of the DRC. The nation is resource-rich, and has large deposits of co balt, coltan, diamonds, copper and gold, as well as non-mineral resources like coal, hemp and timber. Moreover, the DRC has experienced high economic growth since 2003. Its soil is extremely fertile and its vast water resources could meet the entire elec tricity demand of southern Africa.

In theory, agriculture has the potential to reduce the DRC’s import dependency and ensure food security. However, this poten tial remains largely untapped. Although about 70 percent of the population work in agriculture, the industry is largely limited to subsistence farming. Only a small por tion of the soil is irrigated. While several million Congolese make a living from arti sanal mining, 80 percent of the Congolese population are poor and live on less than USD 1.25 a day.

Historically, land ownership and ethnic identity have gone hand in hand in the DRC, which has contributed to worsening inequality and ethnic tensions. Due to pre vailing customary law, migrants often struggle to obtain land in their new com munity, while their claims to their ancestral land fades. In the wake of violent migration in Eastern Congo, however, immigrants with ethnic ties to the Kivu provinces and sufficient resources to buy land are seen displacing the resident population, which is no less problematic.

Land ownership in the DRC is further complicated given that land rights often remain undocumented, and where they are documented, formal and informal claims collide. In formal law, all land was national ized after independence and could be ob tained through long-term concessions. Un der informal customary law, comparatively, land belongs to various clans whose leaders distribute the lots to clan members. Due to rapid population growth and heightened demographic pressure, land has become an increasingly valuable political commodity in the neopatrimonial system. Overlapping claims to land ownership and use have thus become significant sources of conflict. Le gal institutions are hardly capable to re solve such cases, which inevitably hampers investment in more productive agriculture.

As a consequence, the Congolese economy remains overly dependent on the extractive industry, whose profits are largely funneled into the ruling class. Inadequate legal frameworks and a lack of institutional ca pacity inhibit economic development be yond the mining sector. What is more, en demic corruption prevents taxes from being used for the benefit of society, and the exist ing infrastructure deficit brings about high transaction costs for trade. Due to vague legislation, foreign investors often face a le gal gray area in their operations, and the anemic domestic private sector is unable to contribute much to economic growth.

The foreign investment that does occur is predominantly concentrated in the extrac tive sector, and Chinese companies are in creasingly entering into partnerships with the Congolese government. China is now the DRC’s largest trading partner, replac ing the EU. The so-called Sicomines deal of 2007 is a prime example of this partner ship, and was struck between Chinese commodity giants and the Congolese gov ernment. At six billion dollars, the contract volume of the “resource-for-infrastructure” deal exceeded the annual budget of the Congolese state. Although the new part nership with China was celebrated as prog ress for the country’s economic develop ment, the agreement will hardly address the need to diversify in the Congolese economy. While improved infrastructure will certainly facilitate trade and transport, it will not affect systemic obstacles like po litical accountability. Since mining deals are struck directly between the Congolese state – sometimes only by those closest to the president – and international extractive giants, there is no political accountability to the Congolese public, which often hin ders the overall development of the DRC.

Vested Interests in Insecurity

The nature of the political and economic system in the DRC results in a precarious combination of a fragmented elite, an un stable political economy, conflicts over land and influence with inadequate dispute set tlement mechanisms, and external interfer ence. Political decentralization has intensi fied rather than mitigated the struggle for office and power. The number of armed groups has thus increased sharply, particu larly in the chronically unstable Kivu prov inces in the Eastern part of the country.

While the exploitation of raw materials plays a significant role in financing such armed groups, evidence shows that – con trary to popular belief – resource wars are not a main cause of conflict in the DRC. Instead, pillaging and the extortion of the local population are often much more im mediate financial opportunities for armed groups and fighters. Paradoxically, the local self-defence groups that form due to the ensuing security vacuum, often based on ethnicity, further perpetuate insecurity and conduct violent attacks to win influence and land. While the self-defence groups are mostly confined to remote areas, gangs, crime, and repressive security forces sow insecurity among the urban population.

In many provinces, pervasive insecurity has been an integral part of Congolese politics for decades. While smaller, local uprisings have usually received little public attention, armed groups that gain enough power to threaten traditional structures and supra-regional stability are quickly quashed through the government’s political and military intervention. Until 2011, the gov ernment regularly integrated rebel groups into the government and the national army. This weakened the cohesion of the army and encouraged the development of paral lel chains of command. Internationally-supported technical programs designed to increase the presence of the state and secu rity forces, or to disarm and demobilize armed groups, were thus rendered futile.

Thanks to various reforms and new leader ship since 2013, the army has become more powerful and effective. Like other state in stitutions, however, in many places it is still perceived as predatory and, even in con junction with MONUSCO, does not have the capacity to combat all armed groups.

Outlook

The enduring security, political and eco nomic challenges were at the forefront of the recent presidential election, with many viewing the election with measured opti mism for the future. Yet, given Kabila’s continuing role in Congolese political and economic life, it is unlikely that the new era of ‘democracy’ will fundamentally change the entrenched neopatrimonial system. As his actions following the election of a well-liked opposition candidate indicates, Kabi la does not feel threatened by the new or der, nor does he expect significant change in society or to his circumstances. The frag mented political and military elite may be recalibrated somewhat under the new pres ident Tshisekedi, but will probably remain largely unaltered.

The infrastructure deficit throughout the country hampers both the projection of statehood and economic progress beyond urban areas. Chinese investments in infra structure can strengthen trade and eco nomic activity to some extent. However, corruption, nepotism, and the continued parallel exercise of formal and informal power will continue to impede economic progress. As long as the fundamental prob lems of poverty, ineffective mediation re garding land disputes, weak civil society, and political elite power struggles are not resolved by domestic and foreign political will, underdevelopment and insecurity will persist in the DRC.

Recent Issues in the CSS Analyses in Security Policy Series

- Military Technology: The Realities of Imitation No. 238

- The OSCE’s Military Pillar: The Swiss FSC Chairmanship No. 237

- Long-distance Relationships: African Peacekeeping No. 236

- Trusting Technology: Smart Protection for Smart Cities No. 235

- The Transformation of European Armaments Policies No. 234

- Trump’s Middle East Policy No. 233

About the Authors

Larissa Jäger is an Africa expert and was a research assistant at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich until 2018.

Benno Zogg is a Researcher at CSS. He focuses on development and security and is co-author of Mali’s Fragile Peace (2017).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.